The new Pixnapping side-channel attack allows a malicious Android app to extract sensitive data without any permissions by stealing pixels displayed by other apps or websites.

The attack makes it possible to reconstruct a wide range of data, including messages from secure messengers, emails, two-factor authentication (2FA) codes from apps like Google Authenticator, and so on. In short, anything that is displayed on the device’s screen.

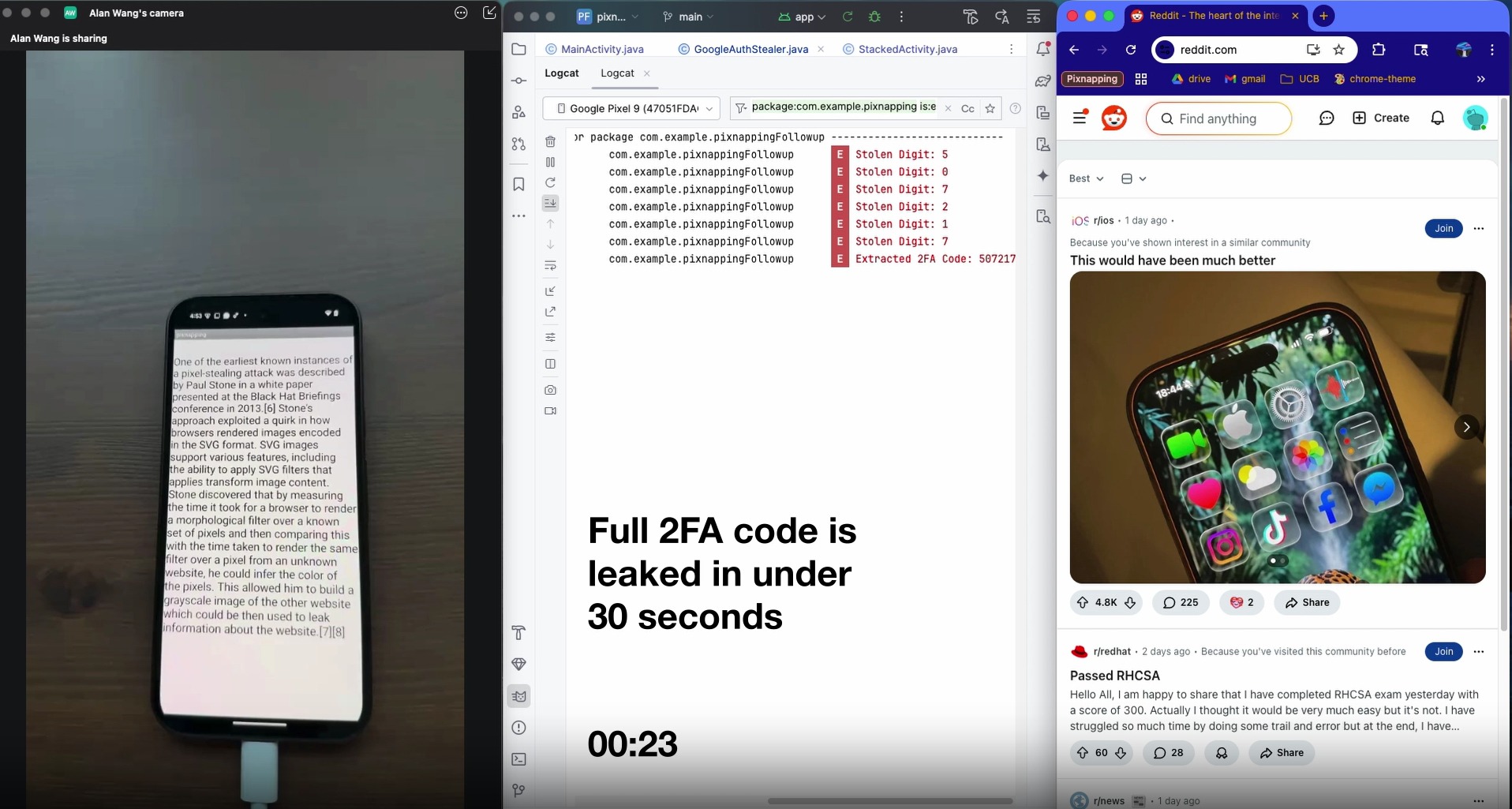

Pixnapping was developed and demonstrated by seven researchers from U.S. universities. The attack works on fully up-to-date modern Android devices and makes it possible to steal 2FA codes in less than 30 seconds.

Google engineers attempted to fix the issue (CVE-2025-48561) as part of the September updates for Android, but researchers managed to bypass the protection, and a more effective solution is expected to be released in December 2025.

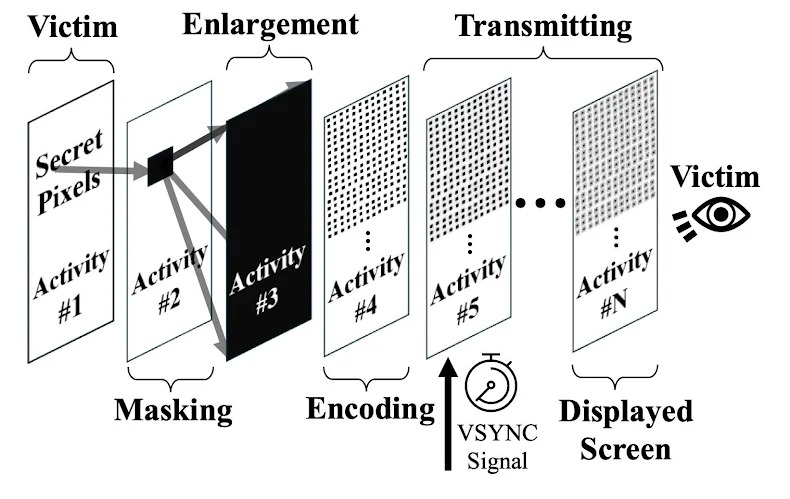

The attack begins with a malicious app abusing the Android intent system by opening the target app or a web page so that its window is handed off to the system compositor (SurfaceFlinger), which is responsible for compositing multiple windows when they are visible simultaneously.

At the next stage, the malicious app identifies the target pixels (for example, those forming a digit of the 2FA code) and, through a series of graphics operations, determines whether they are white or not.

It is possible to isolate each individual pixel by opening what the researchers call a “masking activity,” which runs in the foreground and obscures the target application. The attacker then makes the masking window “fully opaque white, except for the pixel at the attacker-chosen position, which is made transparent.”

During a Pixnapping attack, isolated pixels are magnified using the blur implementation in SurfaceFlinger, which creates a stretching effect.

Once all the target pixels have been reconstructed, a technique similar to OCR (Optical Character Recognition) is used to recognize each character or digit.

“Conceptually, it looks as though a malicious app is taking a screenshot of screen contents it shouldn’t have access to,” the researchers said.

To steal data, the researchers used the GPU.zip side-channel attack, which exploits graphics data compression in modern GPUs to exfiltrate visual information. Although the data leakage rate is relatively low—between 0.6 and 2.1 pixels per second—the researchers optimized the attack so that 2FA codes and other sensitive data can be stolen in under 30 seconds.

Experts tested Pixnapping on Google Pixel 6, 7, 8, and 9 devices, as well as the Samsung Galaxy S25, running Android versions 13 through 16. All of them proved vulnerable to the new side-channel attack. Since the fundamental mechanisms the attack relies on are present in older Android versions as well, most older Android devices are likely vulnerable, too.

In addition, the researchers analyzed nearly 100,000 apps from the Google Play Store and found hundreds of thousands of invocable actions via Android intents, indicating the attack’s broad applicability.

In a technical document published by the authors of Pixnapping, the following examples of data theft are listed:

- Google Maps: Timeline entries occupy about 54,264–60,060 pixels, and without optimization, reconstructing a single entry takes 20–27 hours depending on the device;

- Venmo: activities (profile, balance, transactions, statements) can be opened via implicit intents, and the account balance area occupies about 7,473–11,352 pixels. Exfiltration without attack optimization takes 3–5 hours;

- Google Messages (SMS): explicit and implicit intents allow opening conversations. The target areas occupy approximately 35,500–44,574 pixels, and reconstructing them without optimization takes 11–20 hours. The attack distinguishes sent and received messages by pixel color — blue vs. others or gray vs. others;

- Signal (private messages): implicit intents also provide access to conversations. The target areas occupy on the order of 95,760–100,320 pixels, and reconstructing them without optimization takes 25–42 hours. The attack works even with Signal’s Screen Security feature enabled.

Google and Samsung promise to fix the issue by the end of the year, but no GPU manufacturer has yet announced plans to address the GPU.zip side-channel issue.

As mentioned above, although the original exploitation method was addressed in September with the release of a patch for CVE-2025-48561, the researchers managed to bypass this patch. However, Google explains that using the updated data exfiltration technique requires specific information about the target device, which makes the attack much more complex.

The company also emphasized that no evidence of Pixnapping being exploited in real-world attacks has been found.