In a previous article, “Using little‑known Google features to uncover hidden data,” we broke down how to craft search queries that return direct links to sensitive information and lists of vulnerable hosts. These queries are known as Google Dorks. Google is well aware of them and tries to clamp down on the most dangerous ones. But the list keeps growing, as does the roster of potential targets they uncover. Let’s walk through some of the most interesting examples.

warning

This content is intended for security professionals and those looking to enter the field. All information is provided for informational purposes only. Neither the editorial team nor the author accepts any responsibility for any harm that may result from using the materials in this article.

Useful Google Search Operators

Among all of Google’s advanced search operators, we’re primarily interested in four:

-

site— restrict results to a specific site or domain; -

inurl— require the search terms to be part of the page URL; -

intitle— search for terms in the page title; -

extorfiletype— find files of a specific type by extension.

Also, when composing a query, keep in mind several operators that are defined using special characters.

- | — vertical bar (pipe), i.e., the OR operator (logical OR). Returns results that contain at least one of the terms listed in the query.

- “” — quotes. Searches for an exact phrase match.

- – — minus. Used to clean up results by excluding pages that contain the terms following the minus.

- * — asterisk (star). Used as a wildcard meaning “anything/any characters.”

Hunting for Passwords

Credentials for all kinds of web services are a tempting target for hackers. Sometimes you can get them in literally one click—well, more precisely, with a single Google query. For example, something as simple as:

ext:pwd (administrators | users | lamers | service)

This query will find all files with the . extension that contain at least one of the words in parentheses. The results will be noisy, though. You can clean them up by filtering out end‑user content and other low-quality pages. For example:

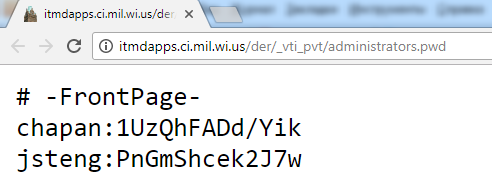

inurl:_vti_pvt/administrators.pwd

This is a targeted query. It will find files with descriptive names on servers running FrontPage Extensions. The eponymous editor is long gone, but its server-side extensions are still in use. Account credentials in administrators. are encrypted with DES. They can be cracked with John the Ripper or a cloud-based password-cracking service.

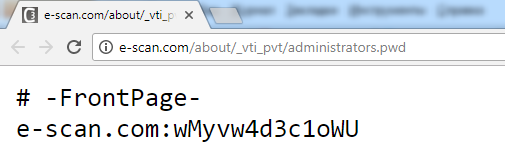

Same goes for FTP: look for configuration files like .cfg or .ini. They often store usernames in plain text and passwords with weak encryption. For example, a simple search query will turn up lots of Asian sites where a locally developed, insecure FTP server is popular.

inurl:"[FFFTP]" ext:ini

On the one hand, by default it uses AES encryption in CBC mode with the SHA-1 hash function. On the other hand, its cryptographic implementation is weakened, and there’s a ready-made tool for brute-forcing such passwords.

Web Reconnaissance

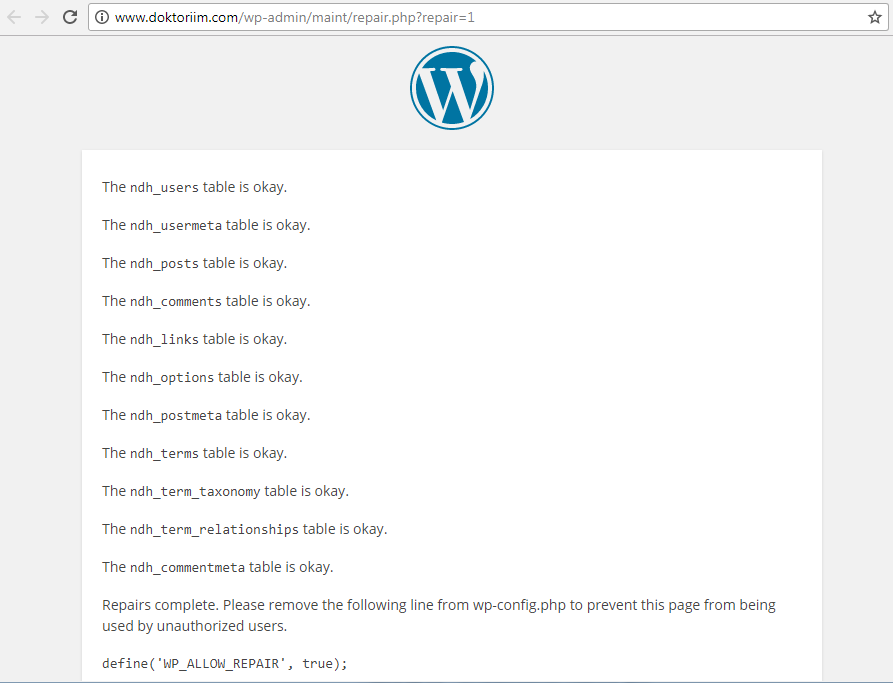

Sometimes it’s useful to map out a site by pulling a list of its files. If the site runs on WordPress, the file repair. contains the names of other PHP scripts. The inurl operator tells Google to search for the following keyword in the URL. If we used allinurl, it would require all the specified keywords to appear in the URL, and the results would be noisier. So it’s enough to run a query like this:

inurl:/maint/repair.php?repair=1

As a result, you’ll get a list of WordPress sites where the database structure can be viewed via repair..

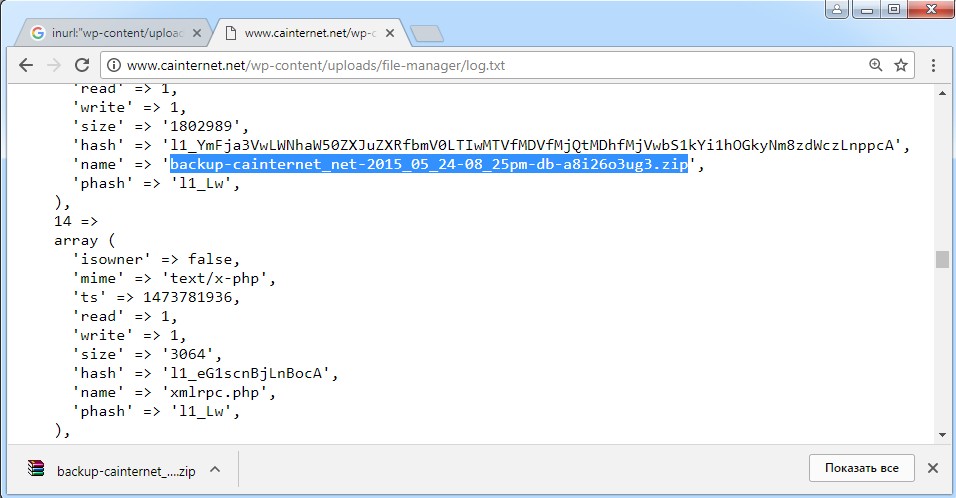

WordPress installations with unnoticed misconfigurations cause admins endless headaches. Even a publicly accessible log can reveal at minimum the names of scripts and uploaded files.

inurl:"wp-content/uploads/file-manager/log.txt"

In our experiment, a trivial query uncovered a direct link to the backup in the logs, and we were able to download it.

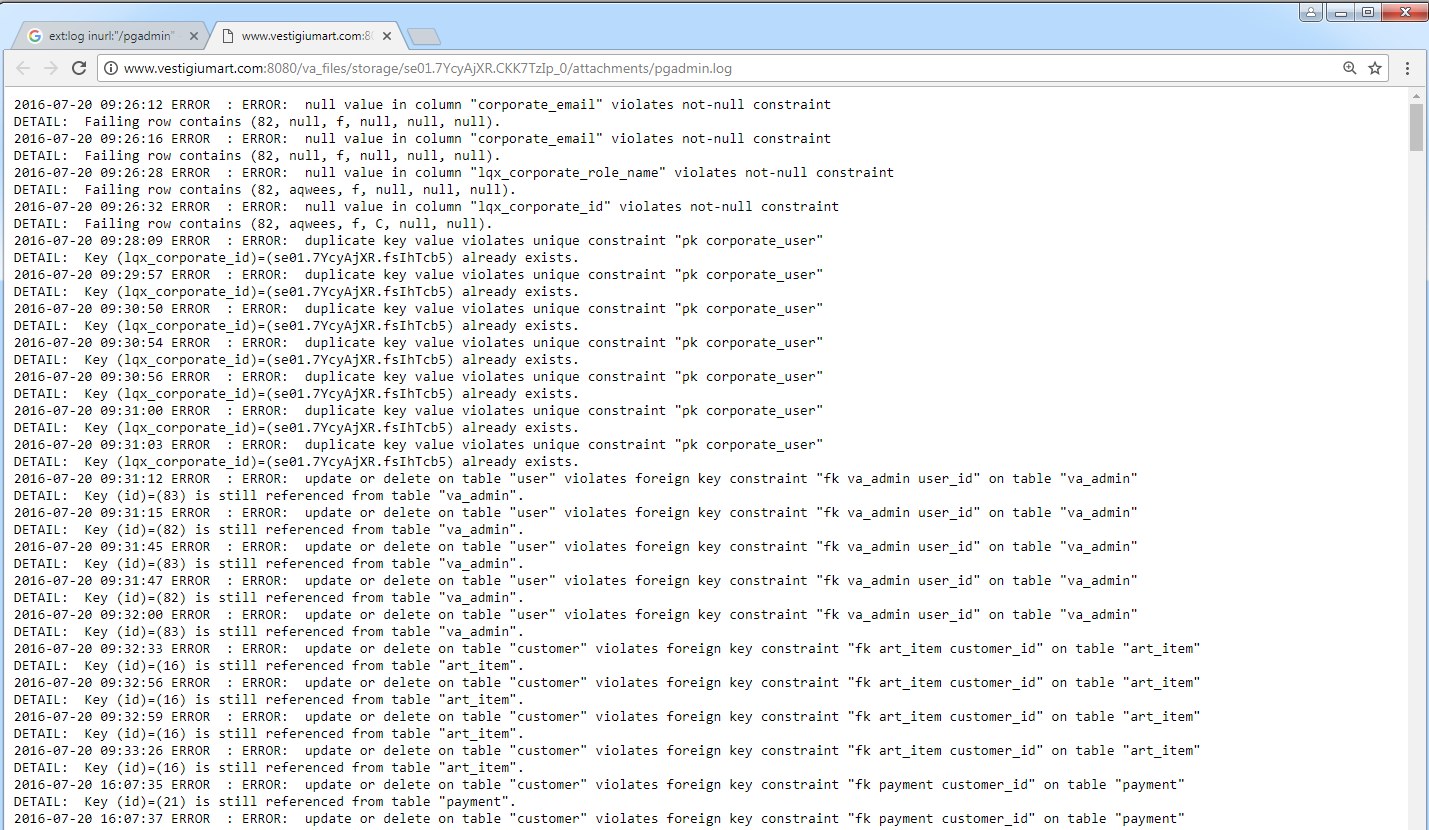

A lot of valuable information can be pulled from logs. You just need to know what they look like and how to tell them apart from the multitude of other files. For example, the open-source database interface called pgAdmin creates a log file named pgadmin.. It often contains usernames, database column names, internal addresses, and similar data. You can locate the log with a simple query:

ext:log inurl:"/pgadmin"

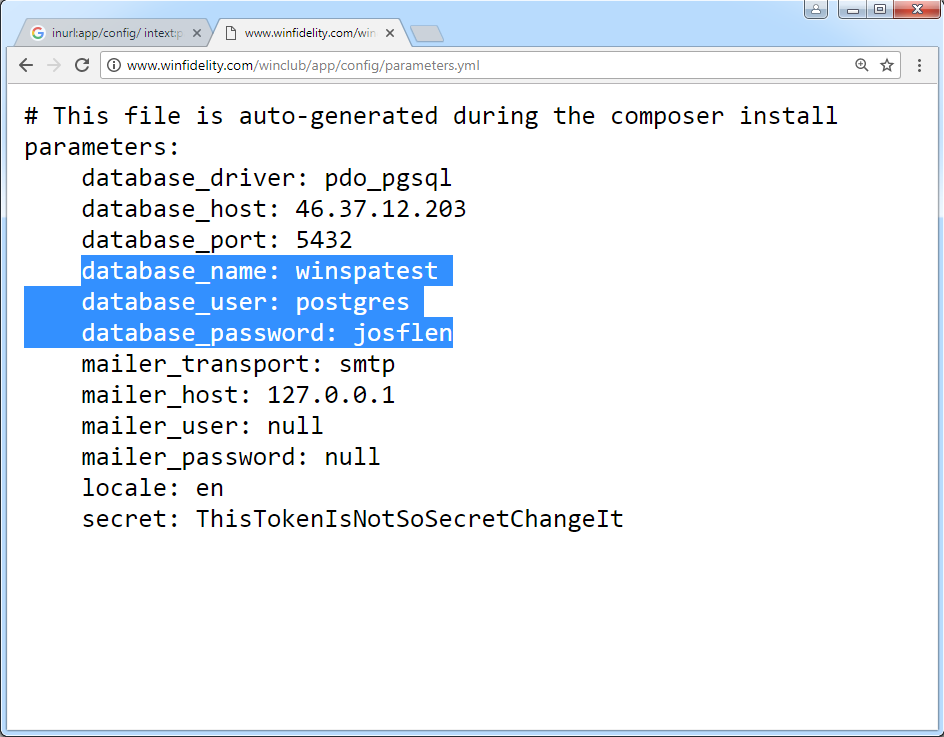

There’s a common belief that open source equals secure code. In reality, openness only means the source can be inspected—and not everyone does so with good intentions. For example, among web app frameworks, the Symfony Standard Edition is popular. During deployment it automatically creates a parameters. file in the / directory, where it stores the database name as well as the username and password. You can find this file with a query like:

inurl:app/config/ intext:parameters.yml intitle:index.of

Sure, the password could have been changed later, but most of the time it remains whatever was set during the deployment phase.

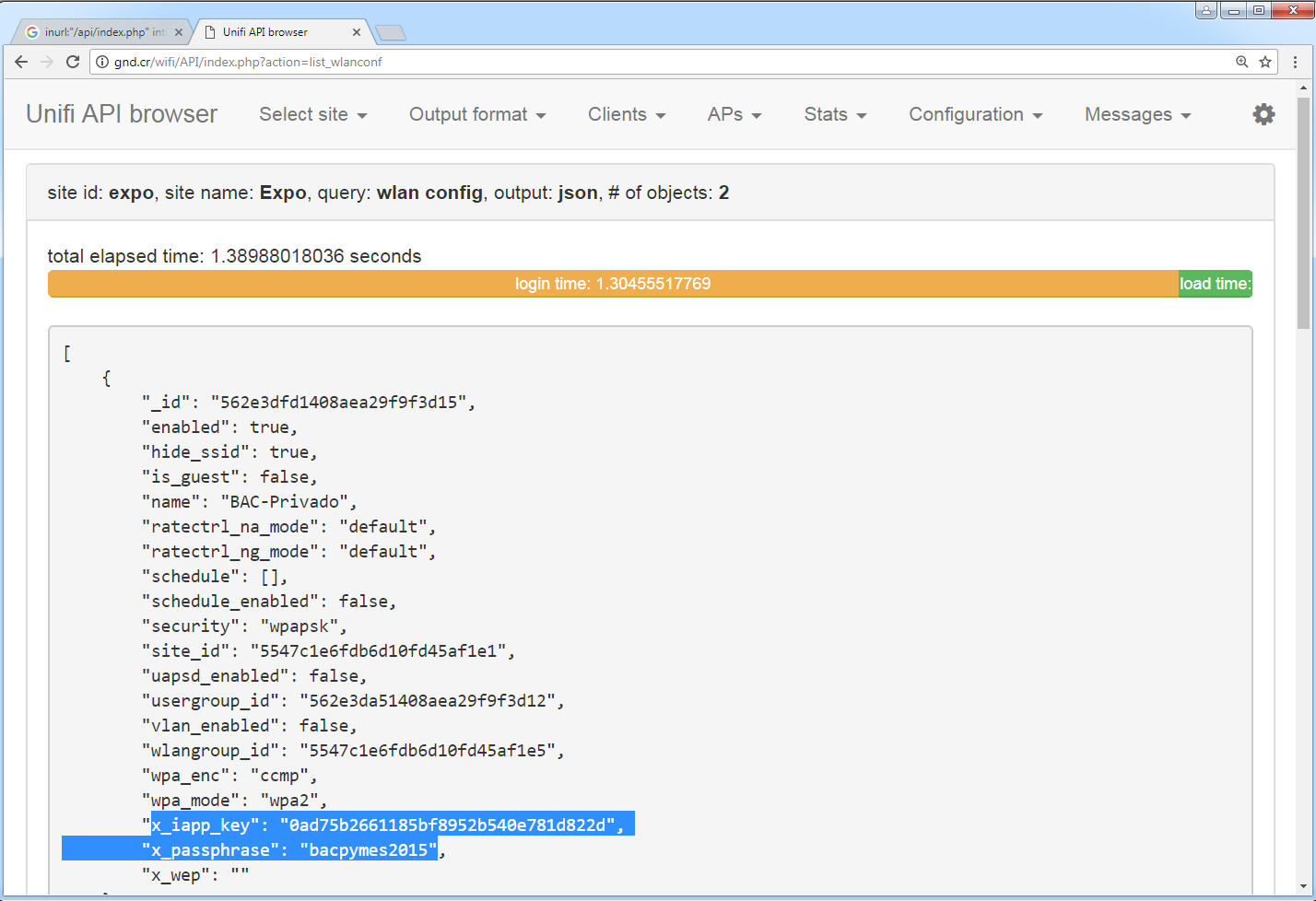

The open-source UniFi API browser tool is increasingly used in corporate environments. It’s used to manage wireless network segments designed for seamless Wi‑Fi roaming—in other words, in enterprise deployments where many access points are controlled from a single, centralized controller.

This utility is designed to display data retrieved via Ubiquiti’s UniFi Controller API. It makes it easy to view statistics, connected client information, and other operational details from the UniFi API.

The developer is upfront about it: “Please do keep in mind this tool exposes A LOT OF the information available in your controller, so you should somehow restrict access to it! There are no security controls built into the tool…” But it seems many don’t take these warnings seriously.

If you know about this quirk and run another narrowly targeted query, you’ll surface a trove of internal data, including application keys and passphrases.

inurl:"/api/index.php" intitle:UniFi

info

General search rule: start by identifying the most specific terms that characterize your target. If it’s a log file, what distinguishes it from other logs? If it’s a password file, where might the passwords be stored and in what format? Marker keywords usually appear in predictable places—such as a web page’s title or its URL. By narrowing the scope and choosing precise markers, you’ll get a raw set of results. Then refine the query to filter out the noise.

NAS for Us

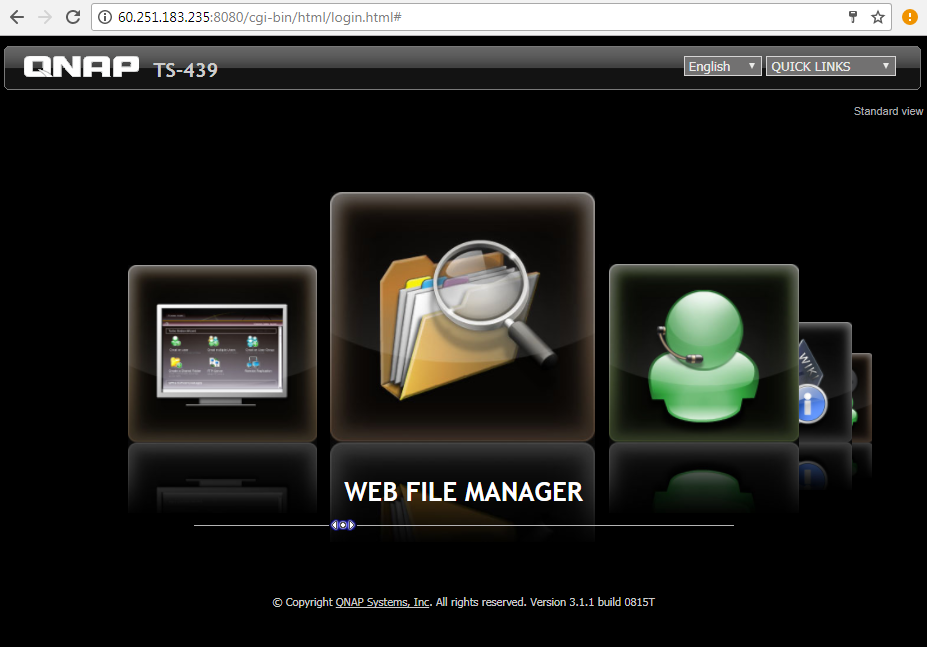

Home and office network storage is popular these days. Many external drives and routers offer NAS functionality. Most owners don’t bother with security and don’t even change default passwords like admin/. You can find popular NAS devices by the characteristic titles of their web interfaces. For example, the query

intitle:"Welcome to QNAP Turbo NAS"

will return a list of IP addresses of QNAP NAS devices. From there, it’s just a matter of finding a poorly secured one.

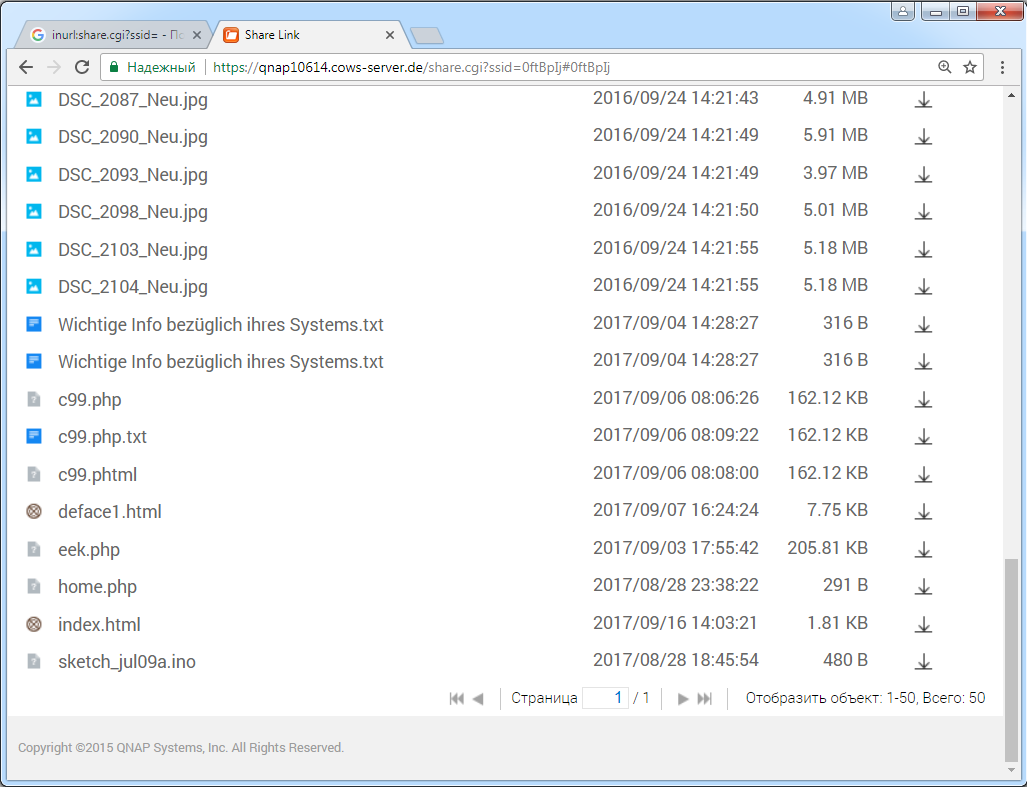

QNAP’s cloud service (like many others) lets you share files via a private link. The problem is, it’s not all that private.

inurl:share.cgi?ssid=

This straightforward query reveals files shared via the QNAP cloud. You can view them directly in your browser or download them for closer inspection.

Hunting for IP cameras, media servers, and other web admin panels

Beyond NAS, advanced Google queries can uncover plenty of other network devices managed via a web interface. These often rely on CGI scripts, so the file main. is a promising target. However, it can show up just about anywhere, so it’s better to refine the query—for example, by appending a common parameter like ?next_file. In the end, you get a dork of the form

inurl:"img/main.cgi?next_file"

Most often, this is how IP cameras are found. For more on discovering and exploiting them, see the article “Eyes Everywhere: How IP and web cameras get hacked and how to protect yourself.”

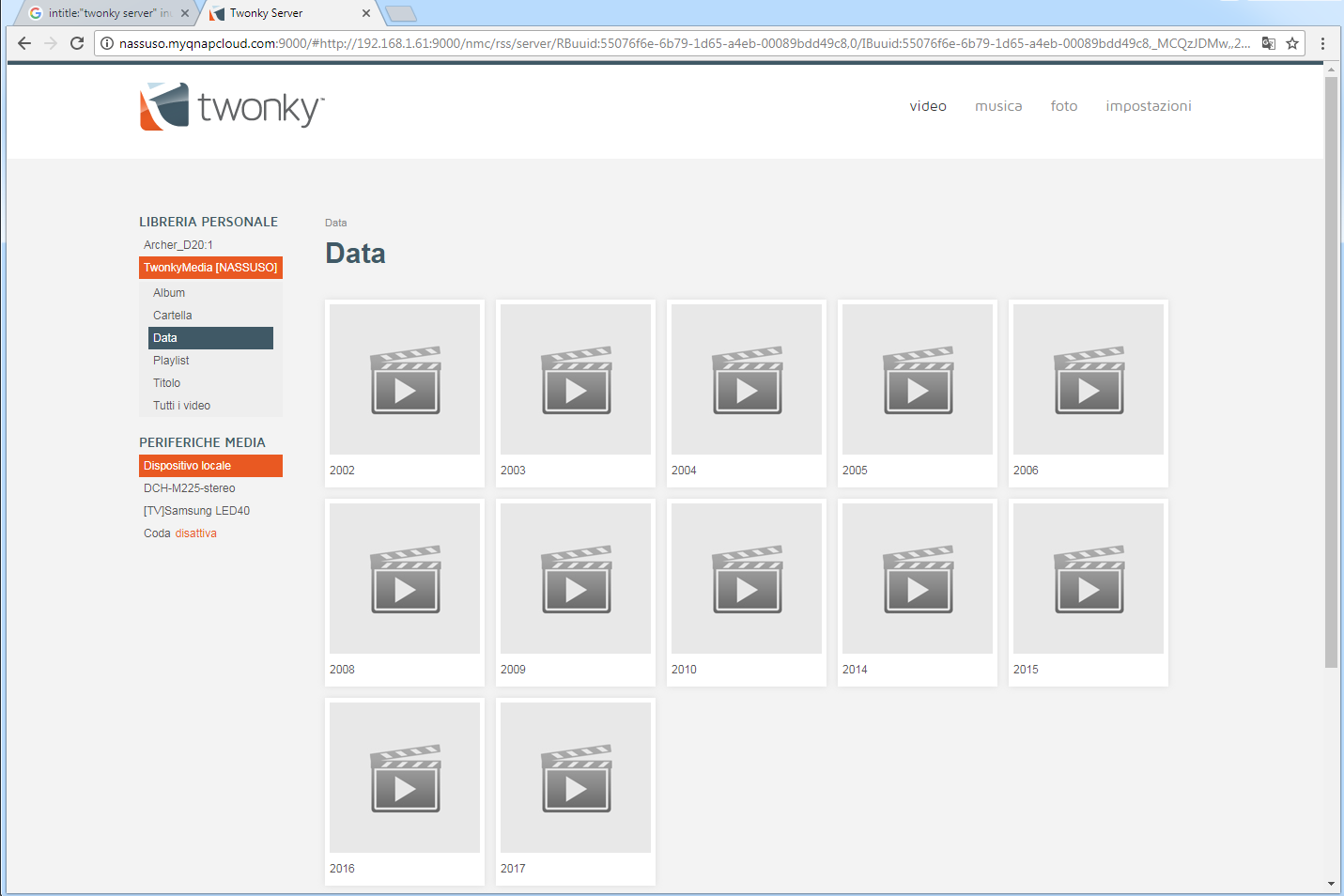

Besides cameras, you can find media servers exposed to the public in a similar way. This is especially true for Twonky servers by Lynx Technology. They have a very recognizable name and a default port of 9000. For cleaner search results, it’s better to specify the port number in the URL and exclude it from the textual content of web pages. The query would look like

intitle:"twonky server" inurl:"9000" -intext:"9000"

Typically, a Twonky server is a large media library that shares content over UPnP. Authentication on these servers is often disabled “for convenience.”

Big Data, Big Vulnerabilities

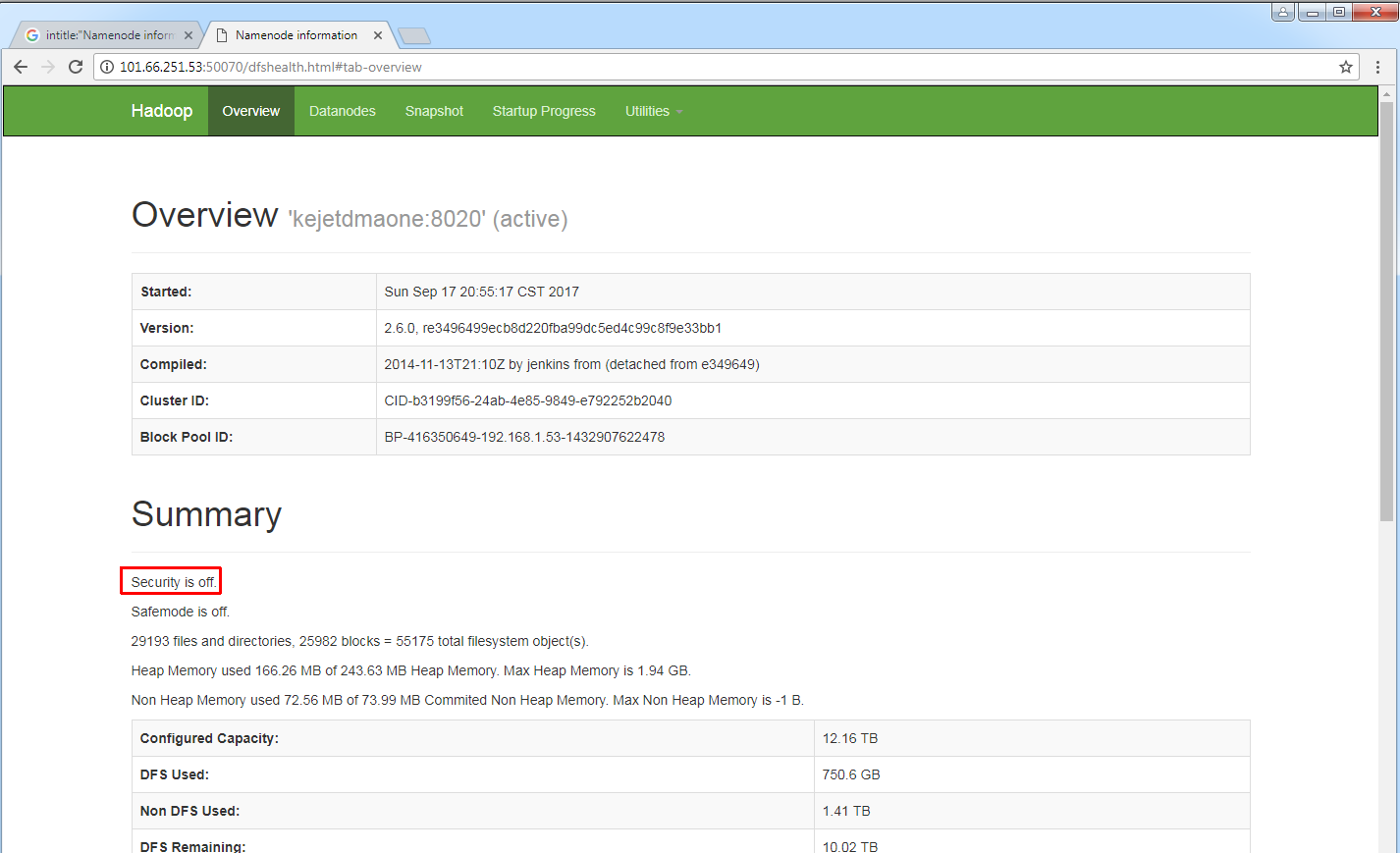

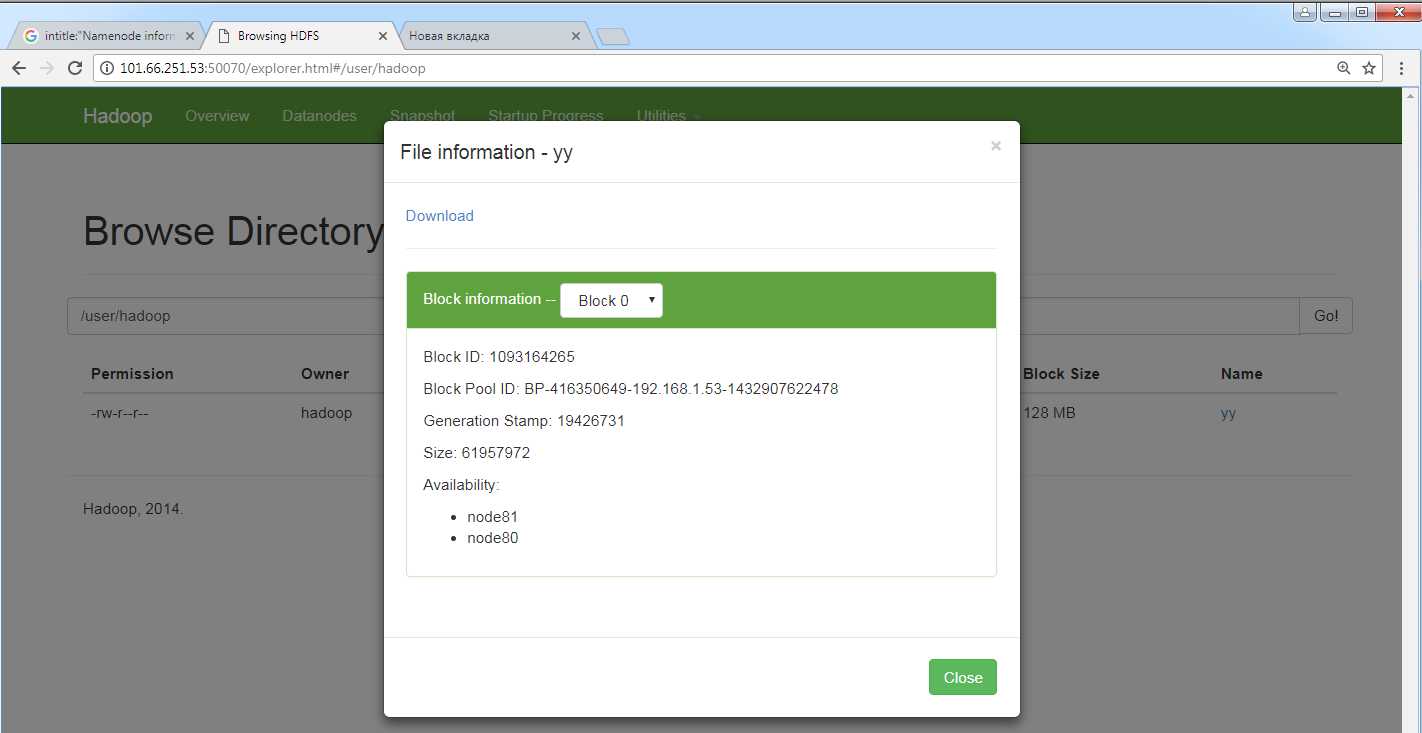

Big Data is a buzzword these days: people assume that slapping “Big Data” onto anything will magically make it better. In reality, genuine experts are rare, and default configurations often turn big data into big vulnerabilities. Hadoop is one of the easiest ways to compromise terabytes—甚至 petabytes—of data. This open-source platform has well-known headers, ports, and service pages that make the nodes it manages easy to find.

intitle:"Namenode information" AND inurl:":50070/dfshealth.html"

Using this concatenated search query, we get results listing vulnerable Hadoop-based systems. You can even browse the HDFS file system right in your browser and download any file.

Conclusions

Google Dork Queries (GDQ) are a set of searches used to uncover glaring security holes—anything that hasn’t been properly hidden from search engine crawlers. For short, these searches are called “dorks,” as are, jokingly, the admins whose systems got popped with GDQ. The best dorks are the fresh ones, and the freshest are the ones you discover yourself. Just don’t get too carried away, or Google will block you… at least until you solve a CAPTCHA. 🙂