Researchers from the University of California, San Diego, and the University of Maryland found that roughly half of geostationary satellite communications are transmitted without any encryption. Over three years of research, the team intercepted confidential data from corporations, governments, and millions of ordinary users using equipment that cost just $800.

The team titled their research “Don’t Look Up,” suggesting that owners of satellite systems relied on the principle of “security through obscurity,” assuming that no one would scan satellites and observe them.

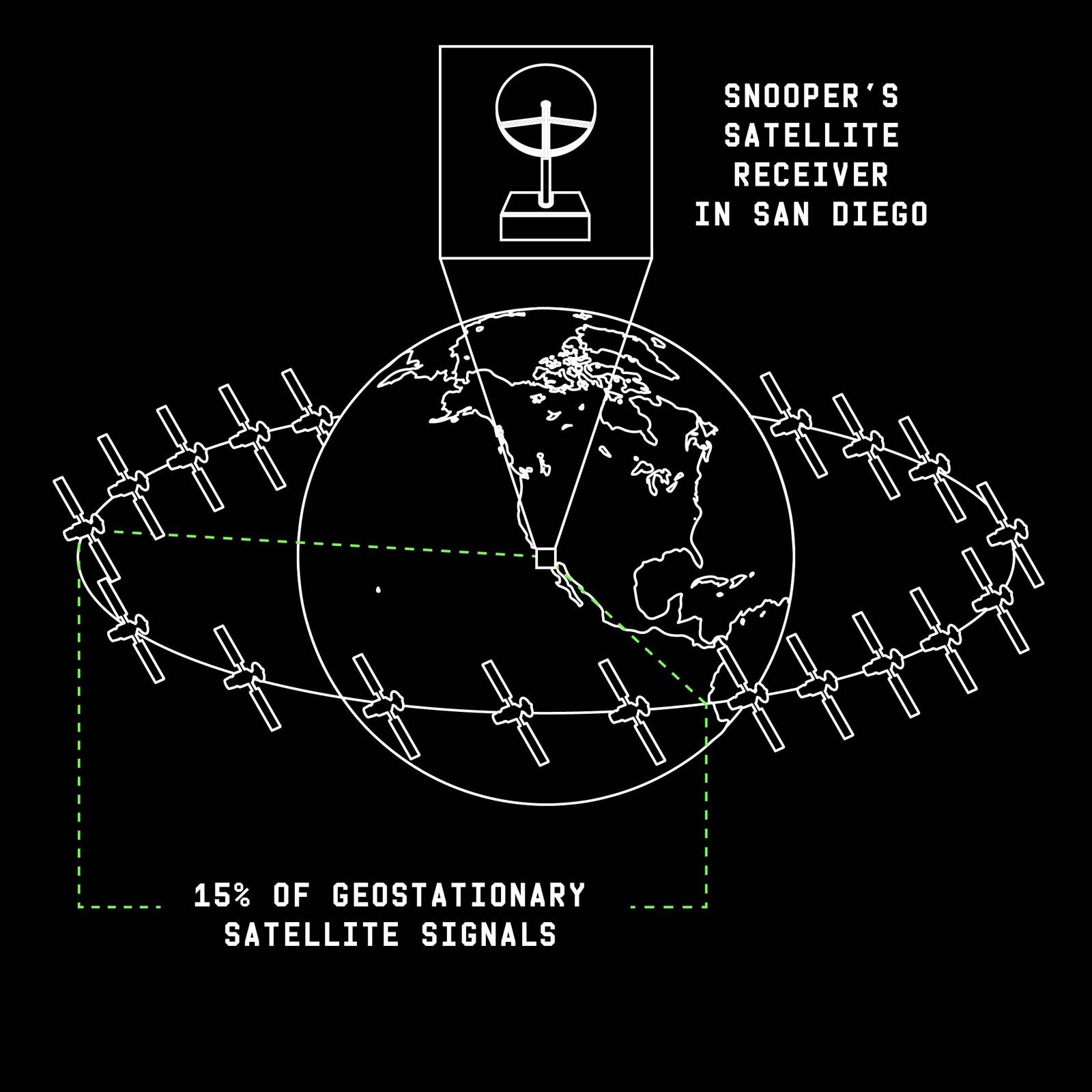

Researchers assembled a satellite signal interception system from off-the-shelf, freely available components: a satellite dish for $185, a motorized roof mount for $335, and a tuner card for $230. After installing the equipment on the roof of a university building in San Diego, they were able to intercept transmissions from geosynchronous satellites visible from their location. Even so, their setup “saw” only about 15% of all satellite communications — mostly over the western United States and Mexico.

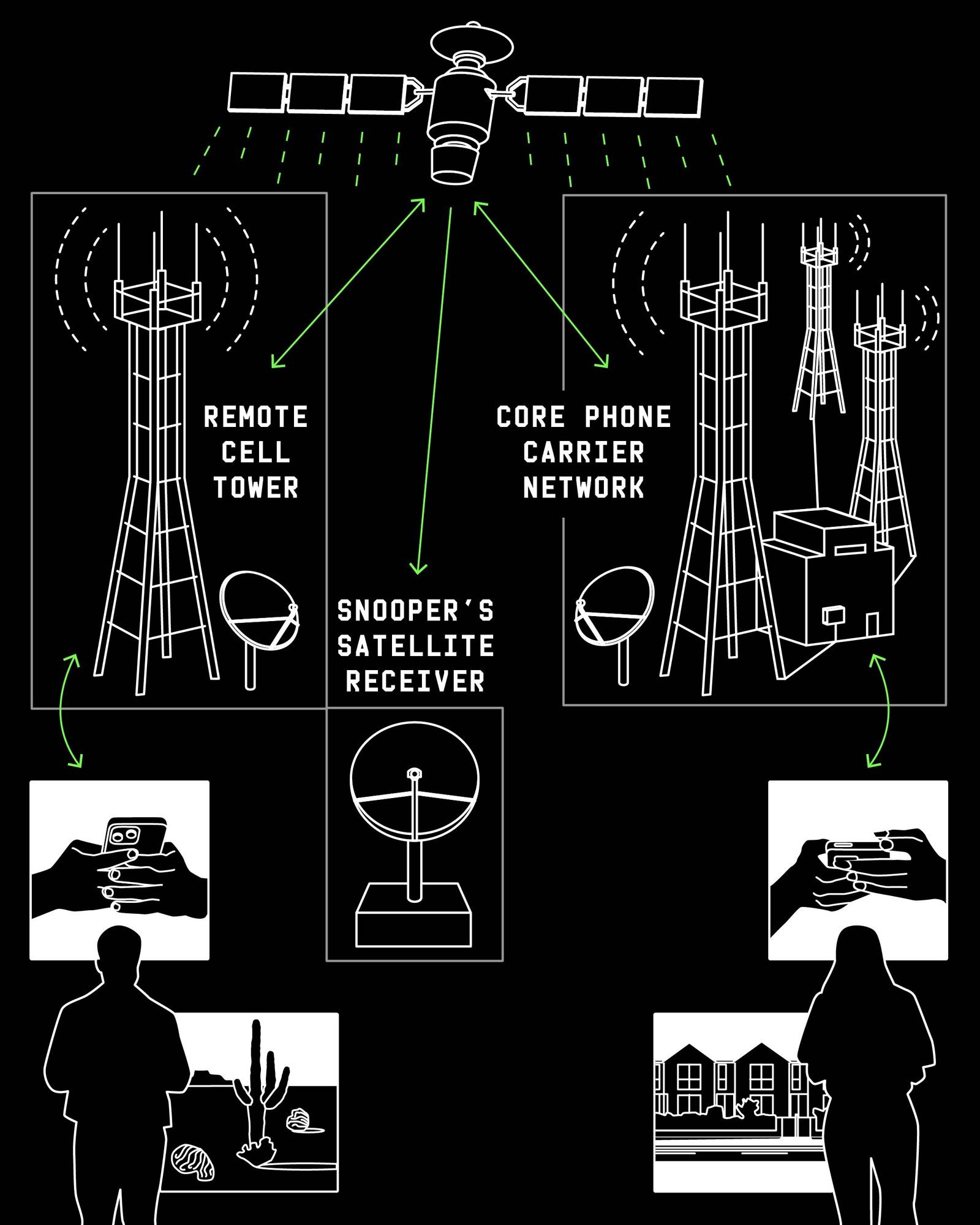

The key focus of the study was the so-called backhaul traffic. In remote regions where laying fiber is not economically feasible, operators deploy base stations that transmit data not over terrestrial links, but via a satellite uplink. A subscriber’s signal reaches the tower and is then sent to a geostationary satellite, which relays it to the operator’s ground station connected to the core network. The problem is that anyone within the coverage area—potentially spanning thousands of kilometers—can receive this signal using a similar antenna. If the data isn’t encrypted, the entire traffic stream becomes available for interception.

The results obtained by the specialists turned out to be alarming. For example, in just nine hours of observation, the researchers intercepted the phone numbers of more than 2,700 T-Mobile subscribers, as well as the contents of their calls and SMS messages. As mentioned above, operators often use satellite communication to transmit data from remote cellular towers located in desert or mountainous regions to the main network. And this data was transmitted in the clear.

“When we saw all this, my first question was: did we just commit a criminal offense? Are we eavesdropping on other people’s phones?” says Dave Levin, a computer science professor at the University of Maryland who participated in the study.

However, in practice the team of experts did not engage in active interception of any communications, but merely passively listened to what their antenna picked up. Levin adds that these signals are “simply broadcast over more than 40% of the Earth’s surface at any given time.”

In addition to cellular communications, the researchers gained access to in-flight Wi-Fi data from ten different airlines, including passengers’ web browsing histories and even audio from the programs streamed to them. Corporate data from Walmart’s Mexican division, communications from Santander Mexico ATMs, and those of other banks were intercepted.

However, the intercepted military and government communications were particularly alarming. The researchers obtained unencrypted data from U.S. military ships, including their names. Even more serious issues were found with the Mexican military: the researchers intercepted command center messages, tracking data on military assets, including Mi-17 and UH-60 Black Hawk helicopters, information about their locations and mission details, as well as intelligence related to counter-narcotics operations.

The situation with critical infrastructure turned out to be no less serious. For example, the Comisión Federal de Electricidad—the Mexican state-owned electric utility with 50 million customers—was transmitting all internal communications in cleartext, from work orders with customer addresses to data on equipment malfunctions. Similar issues were identified on offshore oil and gas platforms.

“This just shocked us. Critical elements of our infrastructure rely on satellite communications, and we were sure everything was encrypted. But time and again it turned out to be in the clear,” says the lead researcher, Professor Aaron Schulman.

Starting in December 2024, researchers began notifying the affected companies and agencies about the issue. Representatives of T-Mobile responded quickly, encrypting transmissions within just a few weeks, but some critical infrastructure owners have still not taken any action.

Experts point out that given the low cost of the equipment, such data interception is within reach of virtually anyone. Moreover, the intelligence services of major nations have likely been exploiting this vulnerability for years using much more powerful equipment. Back in 2022, the U.S. National Security Agency warned about the lack of encryption in satellite communications.

In addition to the research paper itself, the researchers published on GitHub the open-source toolkit they created to analyze data received from satellites, hoping that broad public attention to the issue will finally push the owners of vulnerable systems to implement encryption.

In their study, the experts warn that since only 15% of satellite communications have been examined, the true scale of the problem could be far more serious.