What is this platform, and how did it end up almost disappearing from the market? In this article, we’ll explore the particulars of BlackBerry 10 and how it differs from Android and iOS, take a look at its user interface, and put the marketers’ security claims about this OS to the test.

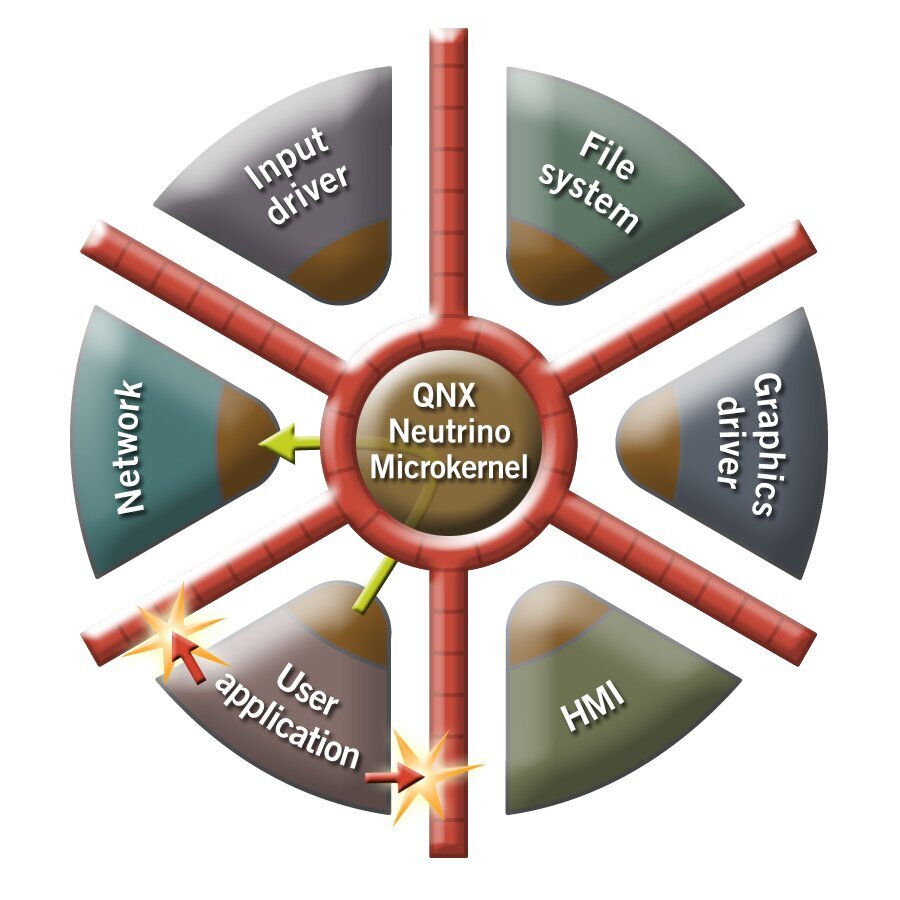

BlackBerry 10 Architecture

Open source, frequent updates, thriving developer communities—none of that applies to BlackBerry 10. Built on the QNX operating system by the Canadian company RIM (Research In Motion), later renamed BlackBerry Inc., BlackBerry 10 inherited QNX’s real-time, microkernel-based design (QNX is pronounced “cue-nix”). QNX used to ship on industrial and telecom gear, power in-car computers, run inside Cisco networking equipment (IOS XR, up to 2013), and eventually made its way into smartphones.

What is QNX, and what can a microkernel offer in a mobile OS? Take Android, for example. It’s built on the Linux kernel, which includes both the core OS services (process and thread management, signal and message passing, timers and synchronization) and a large set of subsystems and services. The Linux kernel contains all the device hardware drivers, filesystem drivers, the network stack, and even things like CIFS (Common Internet File System) support.

A monolithic architecture like this delivers strong performance, but it also introduces a lot of issues around stability and security. What happens if, say, a network driver developer makes a small mistake that leads to a buffer overflow? In the best case, the kernel crashes and the smartphone reboots. In the worst case, someone can exploit the bug by crafting a special network packet. And yes, at that point they gain control over the entire kernel running in ring 0 — in plain terms, control over the whole operating system.

BlackBerry 10 uses the compact QNX Neutrino microkernel, which contains the process scheduler, message-passing system, exception handler, and timers. Everything else—drivers, file systems, services, and applications—runs in user space as separate processes. All of these components communicate with each other through the microkernel, which acts as a message dispatcher between system components.

In this kind of architecture, a bug in the network interface driver will lead to… basically nothing. In the best case, the driver just crashes and the system restarts and reconfigures it. In the worst case, the attacker ends up trapped inside that driver: the driver is compromised, but then what? Sure, they could try to start another service to open a backdoor, but there’s a catch: to do that, you have to send a message to the proc component that’s responsible for spawning processes, and it’s not going to accept messages from a network driver. Maybe they could try to wedge themselves into the network path and tamper with traffic? Well, good luck writing shellcode that can do all that against dynamically changing traffic.

The only real downside of a microkernel architecture is that kernels built on it tend to be slower than monolithic ones. Even so, BlackBerry 10 devices are exceptionally smooth in their core functions, even when powered by the long-obsolete dual-core Snapdragon S4. Even if an app is maxing out that modest CPU, a swipe up from the bottom edge smoothly minimizes it into a window without any lag. You don’t see this level of optimization in Android—or even in iOS, at least in their recent versions.

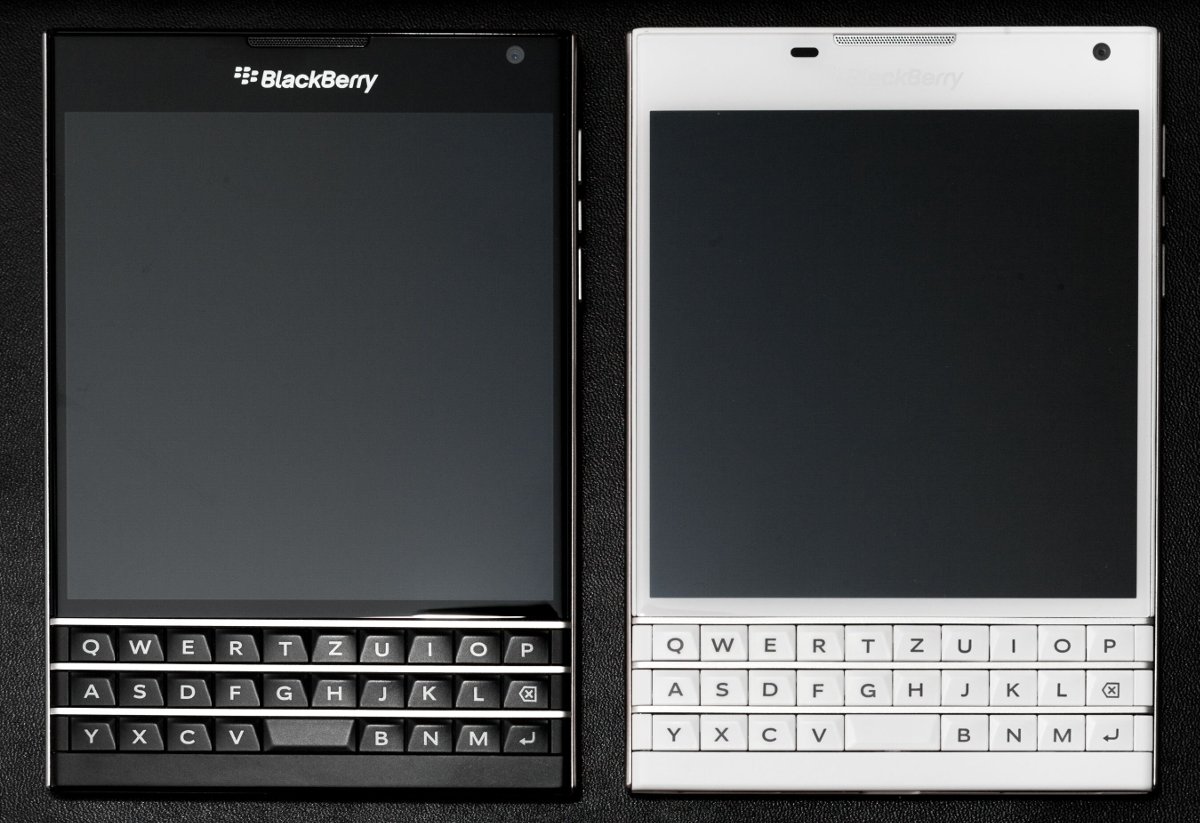

Hardware

A whole range of devices shipped on BlackBerry 10: the all‑touch Z10, Z30, Z3, and Leap, and the keyboard-based Q10, Q5, Classic, and Passport. All of these models—except the Passport—were built on Qualcomm’s Snapdragon S4 platform, which was already outdated by the time they launched. Why did BlackBerry cling so stubbornly to aging hardware, continuing to release devices that were clearly outclassed by the competition?

It comes down to drivers. On Android, chipset vendors like Qualcomm and MediaTek write the drivers for their platforms on their own dime (with development costs baked into the chip price). But for BlackBerry 10, which is based on QNX, those vendors didn’t provide drivers, so the company had to build them itself. Driver development is expensive, complex, and slow; unsurprisingly, BlackBerry decided to reuse as many existing drivers as possible.

Only one of the later devices—the BlackBerry Passport—used the then-new Snapdragon 801 chipset. Unfortunately, the lineup didn’t continue on that chipset.

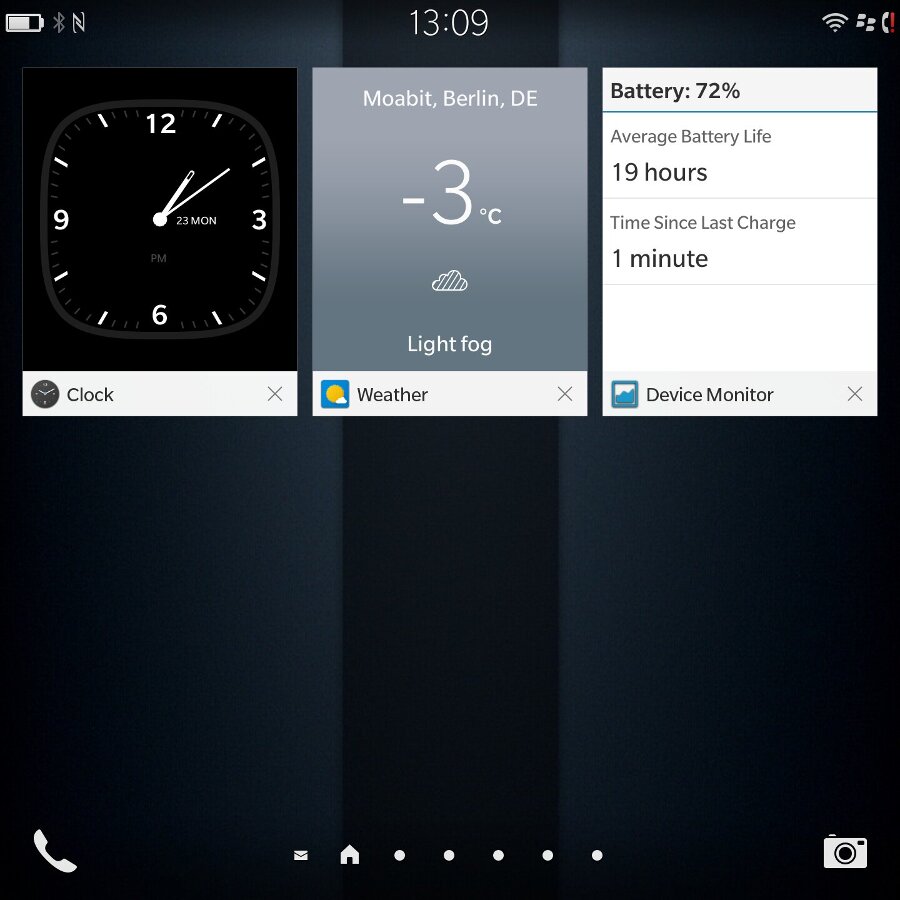

Design and Navigation

BlackBerry 10 was a pioneer of what Google would later call Material Design. Home screens, apps, and settings were all flat cards with shadows that moved and flipped like physical objects. No translucency—everything was strict, logical, and carefully thought through.

BlackBerry 10 doesn’t have widgets per se; instead, when you minimize an app it turns into an Active Frame (a kind of live tile). The clock keeps running, the calendar shows upcoming events, Device Monitor tracks and displays system status, and a two‑factor authentication app shows current codes. Tap the frame and the app instantly returns to full screen. Swipe up from the bottom edge to minimize it back into a tile. Tap the X in the tile’s lower-right corner to close the app and unload it from memory (unlike Android, closed apps are actually removed).

Swipe right and you’re taken to the usual screens with icons for installed apps; it’s very similar to iOS and to those Android launchers that put every app on the home screen.

Overall, when you dig into BlackBerry 10, it feels like the system cherry-picks the best ideas from Android custom ROMs. Wake the screen with a swipe? Check. Turn on the display when you pull the phone from a case or lift it off the desk? It’s there, and it works great. Various gestures and actions triggered by flipping the phone? Those are included too.

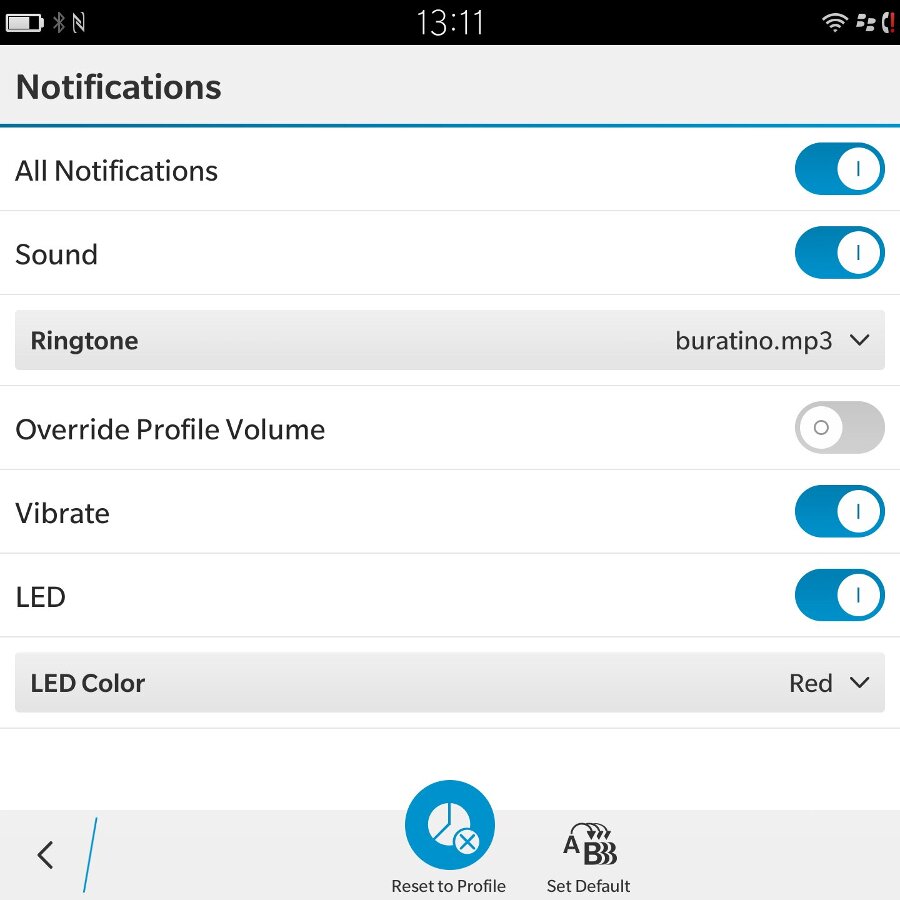

Notifications and Background Process Management

BlackBerry 10 offers superbly granular notification customization. You can define a unique device response for practically any event, adjusting sounds, vibration, and even the LED color. What’s more, notifications can be grouped into profiles—for example, allowing sounds at night only for phone calls (or only from favorite contacts). And those profiles aren’t limited to a simple “night mode”: with third-party apps (which, notably, run in the background), you can switch profiles based on—well—just about anything you can imagine.

You can allow or block background activity on a per‑app basis, and dynamic, granular permission control (prompted on first launch) appeared in BlackBerry 10 long before Android 6.0.

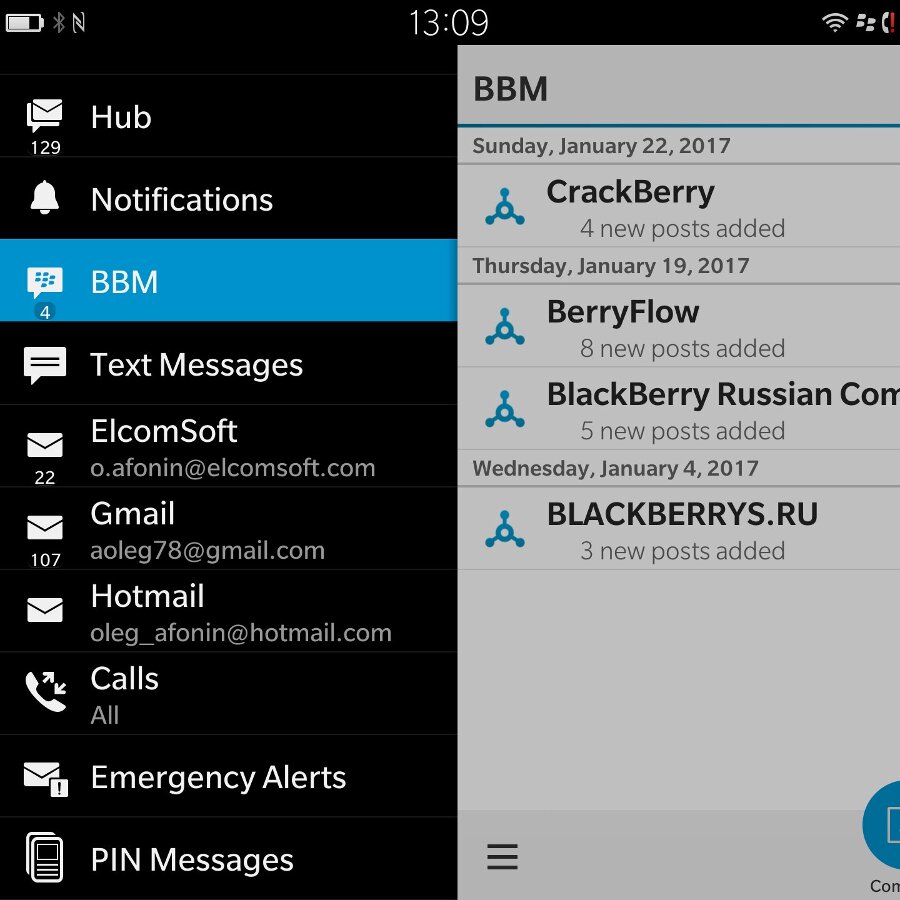

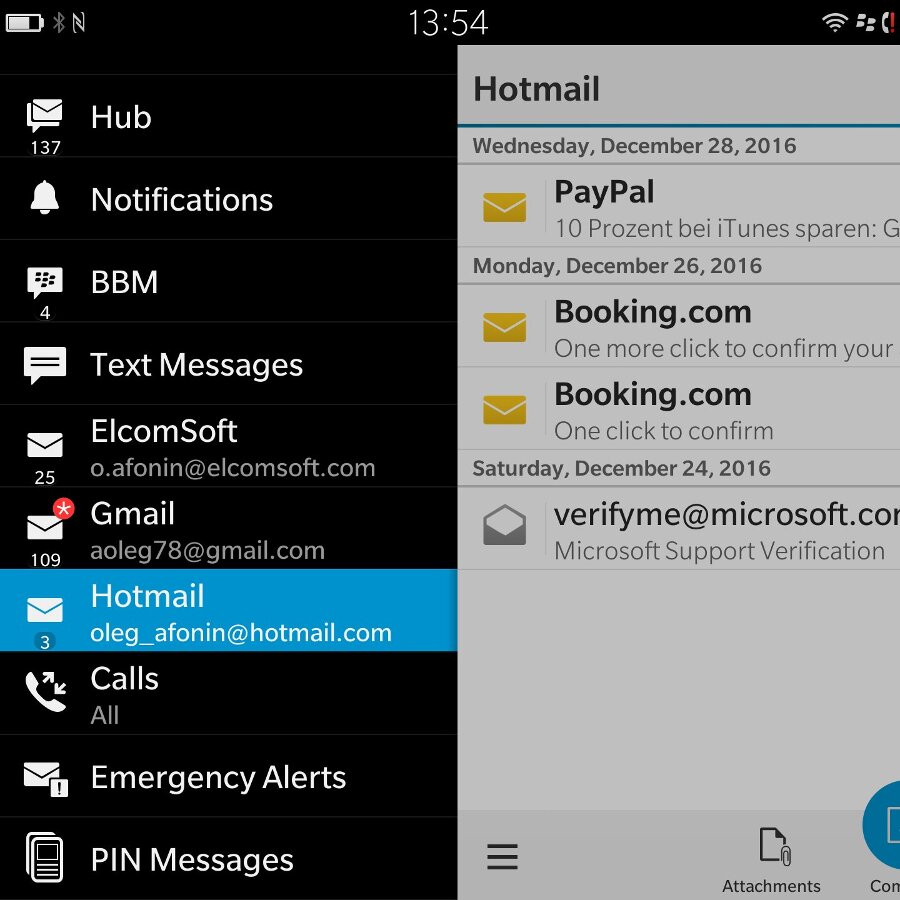

BlackBerry Hub

At the heart of BlackBerry 10 is the BlackBerry Hub. You can bring it up with a signature gesture from anywhere in the OS, no matter which app you’re using. Just swipe up from the bottom edge to pull up the current screen, then flick it to the right, and the Hub opens:

The hub brings together all accounts and all notifications from the apps integrated with it. That includes emails to multiple addresses, tweets on Twitter, Facebook messages, Skype notifications, as well as calls and SMS.

And it’s not just a place to read messages or tweets: you can reply or react without leaving the Hub and, in most cases, without even launching the corresponding app. For someone who needs to be always connected and uses multiple channels to do it, the Hub is an ideal solution. (Personal note: it’s genuinely convenient. After BlackBerry 10, I couldn’t break the habit, so I installed the Android version of the Hub. It’s a pale shadow of its former glory, of course, but still handy!)

That’s the theory. In practice, the platform’s lack of popularity led providers to drop support for it, and Hub integrations started disappearing as a result. The first sign was Facebook announcing that its official app would stop working in May 2016. Then came WhatsApp, whose client will stop working on BlackBerry 10 in July of this year. Skype has long been available only as an Android app (more on those below).

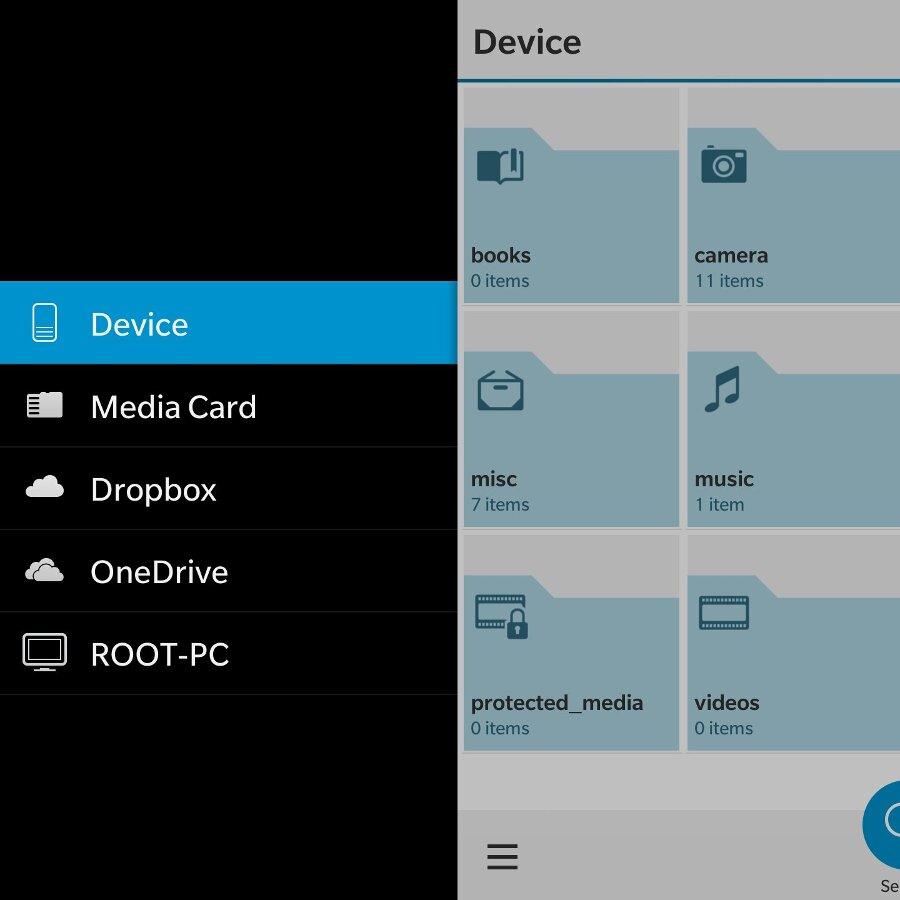

File Access

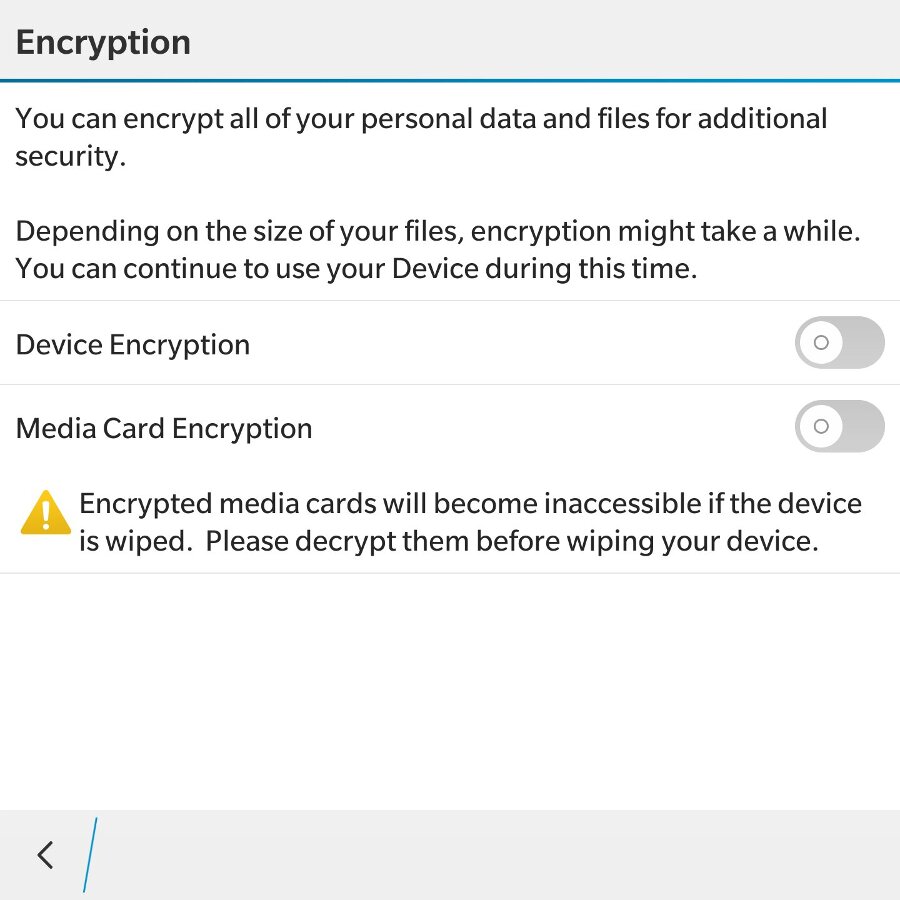

What’s there to say about file access that’s actually interesting? “The device supports memory cards up to…” — yeah, it does. And exFAT and NTFS, too. Still, don’t skip this section: BlackBerry managed to build something genuinely unique, with no counterpart in any other mobile OS (unless you count Windows 8 or 10 running on a tablet).

First off: on BlackBerry 10, you can natively access not only files stored on the device, but also files from popular cloud services—Dropbox, Box.com, and OneDrive—right in the stock file manager. That in itself isn’t unusual; Android also lets you reach any cloud via the Documents/Storage Access Framework. What’s unusual is that BlackBerry 10 can mount those clouds directly into the device’s file system and keep data synchronized between the cloud and the phone. The result is full offline access to your cloud files. Pop in a larger SD card, and all your files are always with you.

BlackBerry 10 also lets you access files stored on your computer or a network drive—even when the phone is on a mobile data connection. You do need BlackBerry Link installed on the computer, but that’s just a minor prerequisite.

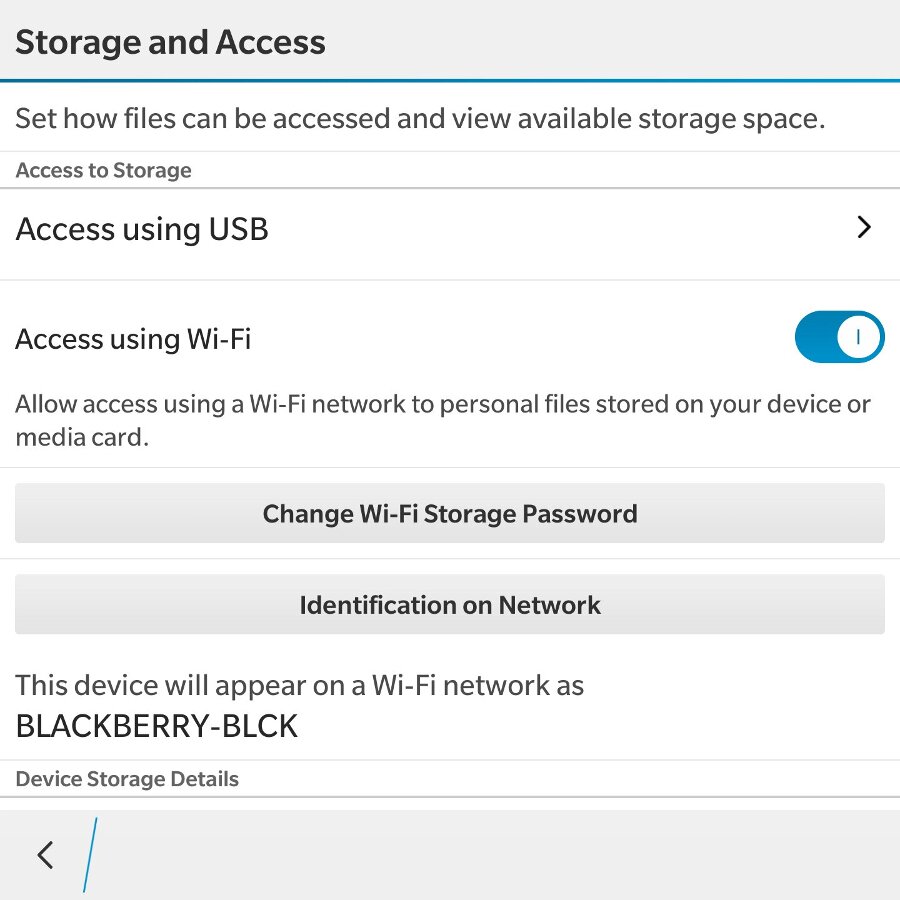

When you connect the phone to a computer, both the internal storage and the SD card become accessible: the BlackBerry Link app mounts them as regular drives. You’ll need to have Link set up on the computer in advance, and you must unlock the phone with its password (you can do this from the computer).

More interestingly, you can access the phone’s file system—mounting it as regular drives—even when the phone isn’t connected to the computer by cable and is just on the Wi‑Fi network.

Yes, you do need to establish a trust relationship between the computer and the phone via the BlackBerry Link app first, but the mere fact that the phone’s files show up on drive E: is practically unheard of with other mobile OSes.

Apps and Android

There are very few apps for BlackBerry 10. If you thought Windows Phone had an app shortage, BlackBerry 10 is an order of magnitude worse. The apps that are available can be downloaded from the built-in BlackBerry World store:

Just because an app is in BlackBerry World doesn’t mean it was built and compiled for BlackBerry. It could just be a standard Android APK with the Google APIs stripped out. Wait… Android?

You already know BlackBerry 10 is built on QNX. What you may not know is that the API-level differences between QNX and Linux are small enough that BlackBerry was able to integrate a full Android subsystem into BB10. The Android layer, based on the 4.3 Jelly Bean runtime, doesn’t run in an emulator; its calls are translated directly into QNX calls. Yes, this call translation and the stricter security model slow the subsystem compared to Android devices with similar hardware, but the ability to run Android apps significantly improves life for BlackBerry 10 loyalists.

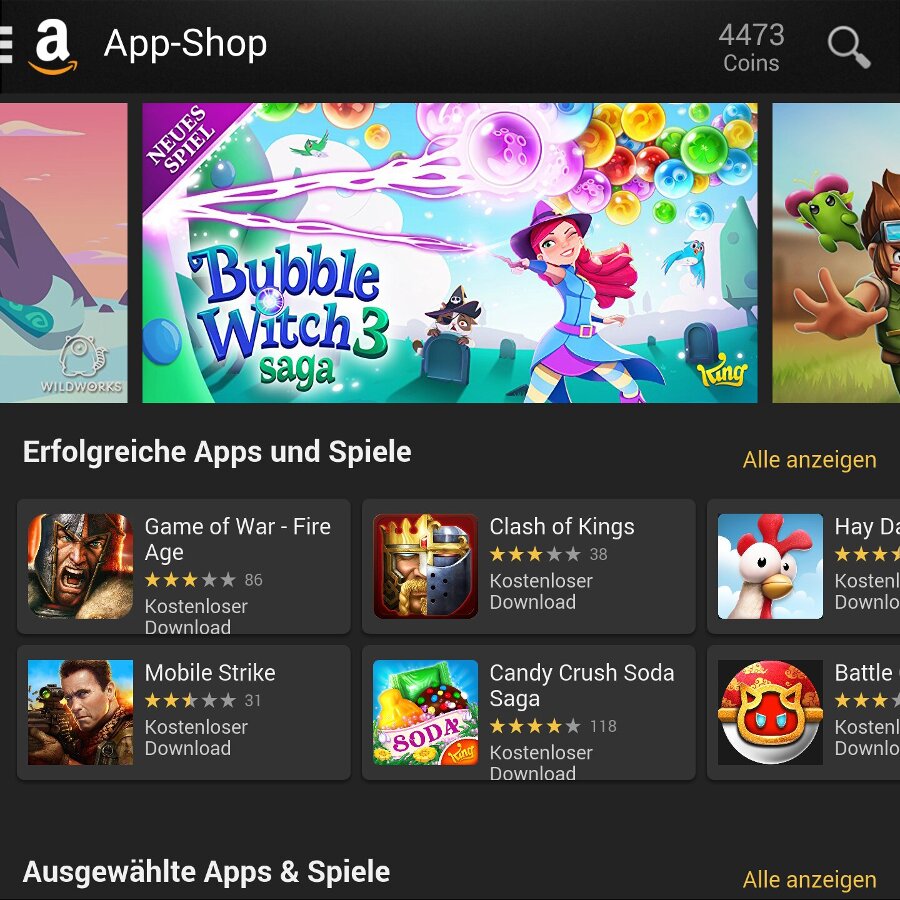

Android apps are available both in BlackBerry World—which doesn’t exactly do the store any favors, since it’s often hard to tell them apart from the much better-performing native apps—and in a secondary storefront, the Amazon Appstore:

The Android runtime is seamlessly integrated into BlackBerry 10. What does that mean in practice? For example, when I choose the Share action, the target list includes both native BB10 apps and Android apps. Or say I open a web link from an Android app and my default browser is Hub Browser or Card Browser (a single-page, card-style browser; on Android the closest equivalent is Chromer). I’ll get the standard card animation, and a right-swipe dismisses the browser card and takes me back to the Android app—just as it would with a pair of native apps.

How well does Android run on BlackBerry phones, and how much does the Android Runtime subsystem actually solve the app gap? Well… it’s a workaround. And a pretty outdated one. Android 4.3 is no longer supported by many apps. Popular messaging apps stop working. The DHL delivery app quit functioning: the website added a CAPTCHA, and the updated mobile app that supports it is only available for devices running Android 4.4 and above.

Even Android apps don’t get full access to the phone’s resources. For example, on the BlackBerry Passport—powered by a Snapdragon 801—Android apps only see two of the four CPU cores. There’s no inertial scrolling from the keyboard or trackpad. If you exit an Android app with the Back gesture, keyboard swipe gestures for paging between screens stop working; that bug went unfixed for about a year and a half, right up until the 10.3.3 OS release. “Probably better than nothing” is a fair description.

Backup and Restore

Backup and restore is a built-in feature of iOS and still a pain point for Android. BlackBerry 10 also has a backup/restore mechanism, and it’s fairly polished. To create a backup you use the BlackBerry Link app, though you can also use the third-party tool Sachesi.

To create a backup, you need to connect the device to a computer and unlock it with the password. The data included in the backup is securely encrypted on the device itself; what leaves the device is an already-encrypted stream that BlackBerry Link or Sachesi simply saves as files. In other words, the backup is effectively created inside the phone. By the way, iOS works the same way, except encryption there is optional and controlled by a backup password.

Search and Voice Assistant

BlackBerry 10 has a powerful system-wide search. Just start typing on the keyboard and results—apps, contacts, emails, and more—appear automatically. There’s no need to launch a separate app for this. The system also includes a solid voice assistant that, again unlike Google’s, works entirely offline.

Firmware and Updates

It’s all familiar and unfamiliar at the same time. Familiar: there are OTA updates. Also familiar: you can wait for them until hell freezes over. This isn’t Apple; obvious bugs either never get fixed, or get grudging, partial fixes months or years later. Monthly security updates? Why would the “most secure system” need those? Two gaping holes—the lack of two-factor authentication and a bypass for BlackBerry Protect’s factory reset protection—still haven’t been fixed after years. The new 10.3.3 firmware is NIAP-certified after a year and a half of development? That only means it’s NIAP-certified; it certainly doesn’t mean that bypassing BlackBerry Protect has suddenly become impossible.

At the same time, BlackBerry has a truly unique mechanism for recovering “bricked” devices using so‑called Autoloaders. An Autoloader is just a large executable—a Windows application that contains everything needed to flash a phone back from a hard brick. No Flash Tools, QPST, QFIL, or any of that scary stuff. You simply download the file from BlackBerry’s site or your favorite forum, run it, and the device comes back to life. Malware? No chance: you can only flash images with a valid, matching digital signature. In all these years nobody’s managed to bypass that requirement, so we can consider the flashing process genuinely safe.

Another interesting point: you can update the firmware piece by piece by sideloading individual apps as BAR files using the Sachesi tool. Naturally, the files must be signed by BlackBerry; otherwise the system won’t accept them. You can install a user app this way, but it won’t gain any special privileges compared to apps installed from the store.

Security

I saved this chapter for last. Ever since BlackBerry 10 was released, the manufacturer has touted the system’s unparalleled security. What does that actually mean in practice, and is it really true that BlackBerry 10 can’t be hacked?

We’ve already covered firmware-level security: the firmware can’t be modified, and privilege escalation is off the table. No one has managed to get root in the Android Runtime (even though it’s the ancient Android 4.3 Jelly Bean) over the entire lifetime of this system.

BlackBerry 10 is the only mobile OS that doesn’t track its users. It doesn’t collect data or phone home to the company’s servers—not even anonymized telemetry. Your location history stays on your device (unless you install Google services and use Google Maps). The voice assistant processes commands entirely on-device, and recordings of your voice aren’t stored on any server (Google, by contrast, uploads and keeps them). Even BlackBerry Travel parses and processes your emails locally, only creating calendar events—cloud or local—if you choose to. Yes, the company can assist law enforcement in exceptional cases (say, going after drug cartels in Colombia), but compared to Apple or Google, both the frequency of such requests and the scope of assistance are a drop in the ocean.

BlackBerry doesn’t really offer its own cloud services, with two exceptions: BlackBerry Protect and the cryptographic key linked to your BlackBerry ID that’s used to encrypt and decrypt device backups. As you may recall, all BlackBerry 10 backups are encrypted—not with a password, but with a cryptographic key tied to your BlackBerry ID. That key is stored in the cloud and, with the right know‑how, can be extracted. Given that BlackBerry ID doesn’t support two‑factor authentication, the security of storing this key is questionable.

By the way, about two‑factor authentication for BlackBerry ID: it doesn’t exist. Big, fat period.

BlackBerry Protect is designed to keep thieves from using a stolen phone. If you factory-reset the device (or enter the wrong password ten times in a row), you’ll have to sign in with the same account that was active before the reset to complete setup. Deleted that account? Tough luck—the device becomes a brick. In theory, at least.

In practice, on 10.3.2 and earlier you could bypass BlackBerry Protect by flashing a developer OS autoloader and then registering the device to a different account. You’d think the 18 months the company spent on 10.3.3 would be enough to close that hole. And indeed, they closed this hole. Now, to bypass BlackBerry Protect you just replace the BlackBerry Protect app in the prebuilt autoloader file. Five minutes—ten, tops. It’s actually more convenient; no need to hunt for a developer autoloader. Amen.

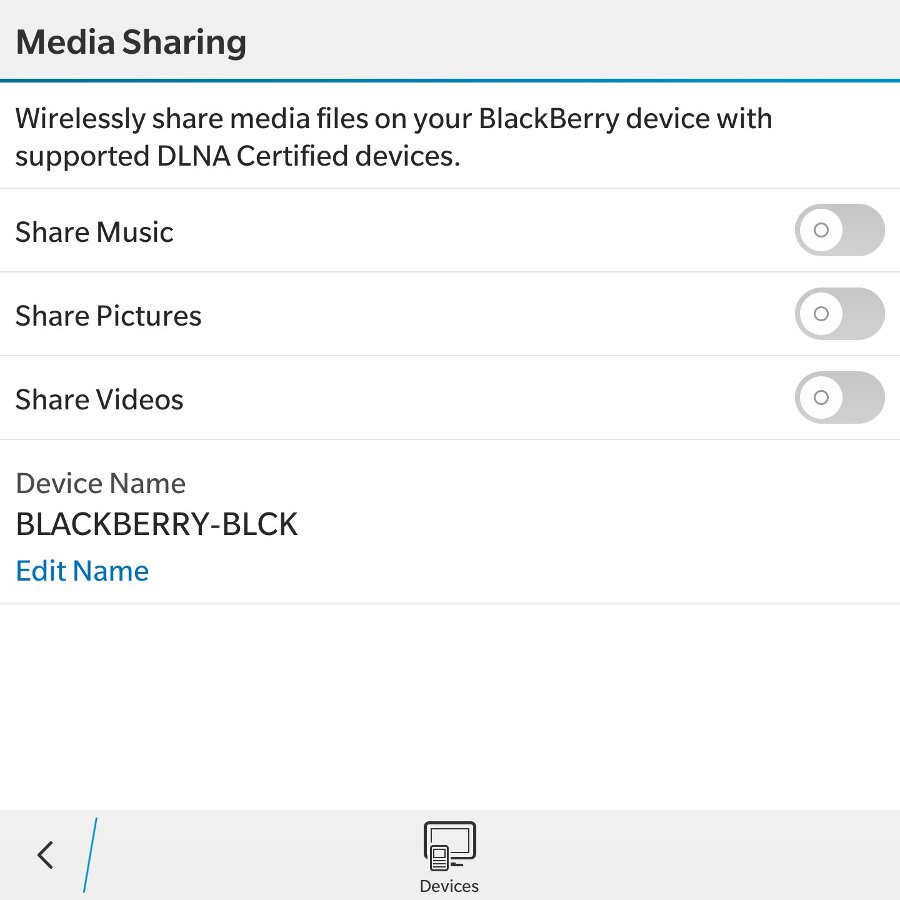

Finally, encryption. In BlackBerry 10, encryption is—surprisingly—optional:

It’s optional. Even with encryption enabled, data protection is essentially single-layer: there’s no system-wide equivalent to iOS Keychain. There is a trusted zone, and it does store the key used to encrypt backups, but the system doesn’t broadly apply an additional encryption layer to protect user data.

To be fair, for 2014 the platform’s security was solid, and it hasn’t evolved much since. That said, in other areas—using a corporate BES instead of BlackBerry’s global servers, and enforcing external security policies (including mandatory encryption)—BlackBerry 10 smartphones remain relevant even today. And when it comes to tracking by the manufacturer or third parties, BlackBerry 10 offers the most privacy. (By contrast, the Android-based BlackBerry Priv offers none of that.)

Conclusion

You could write a lot about BlackBerry 10. There’s BlackBerry Blend—an early take on Continuum that arrived several years before Microsoft brought it to their flagships. There’s BlackBerry Travel, which scans incoming emails directly on the device (important! Google’s equivalent processes mail on its own servers) and adds trip details to your calendar. And there are dozens of other small touches that make the phone easier to use and don’t exist on other platforms.

Unfortunately, that story has come to an end. BlackBerry 10 couldn’t hold on to its market share and was pushed out by Android—a platform with an inconsistent architecture and a murky stance on privacy. The reasons include both BlackBerry’s own decisions and the fact that the early versions of the OS were frankly half-baked.

Yes, if BlackBerry had had BlackBerry 10 three years earlier in the shape we see it now, things might have turned out differently. But the first versions were simply unfinished. There was no Android Runtime at first; then came a limited build that forced developers to “wrap” APKs into BAR files; and only at the very end did they release an Android Runtime without artificial constraints.

History doesn’t deal in what‑ifs. BlackBerry 10 is being phased out, and the company has shifted to developing the Hub+ suite of services and Android firmware installed on devices produced under license by TCL.