This is not an idle question: the number of such demands from U.S. border officials is growing exponentially. Bad precedents tend to spread, and the practice of border checks could be adopted by other countries—in Russia, given recent legislative initiatives, it seems all but inevitable.

How to behave in such a situation, how to protect your information, and whether it’s worth doing at all—this is the focus of today’s article.

What happens at the border?

Several years ago, the United States passed a law allowing border officials to inspect data on the devices of travelers seeking to cross the U.S. border. Initially, it applied only to laptops, USB drives, and other storage media. With the advent of smartphones, the law’s scope was extended to them as well.

The number of digital device inspections is rising quickly. In 2015, roughly 8,500 devices were inspected; by 2016, that number had grown to 19,000. The forecast for 2017 is 29,000 inspections. That’s a striking figure, but the odds of an average traveler being subjected to such an inspection are still low—about eight in 100,000.

What to do — and what not to do

Let’s start with what not to do. Do not lie or actively obstruct a border officer. In the U.S., that’s a criminal offense and can end very badly. Claiming you “forgot your phone’s passcode” won’t work either—you can be held until you remember it. Don’t assume the officer won’t ask about something; for example, if you made a device backup and stored it on a password-protected flash drive, they may well ask for the backup password. Don’t assume they won’t find things, either: hidden containers and photo-encrypting apps are kid stuff—good for fooling parents who got hold of, hopefully not, your phone. A seasoned border agent may see such tricks as a red flag, and your anxiety during inspection can add to their suspicion. Let’s skip the games and focus on what you can actually do to protect your personal information.

Now, onto protection

The most important part of protecting your data is preparing ahead of time. Border control is always stressful, and stress isn’t great for rational decision-making. Here are the things you should plan for.

Are you planning to protect your data at all? Plenty of people don’t use a lock-screen passcode, ignore the fingerprint sensor, and disable built-in encryption. If you’re one of them, you probably have nothing to hide and there’s little point resisting a border officer’s request: next your device will be seized, unlocked, and examined—just without you. And you’ll be the one to bear all the consequences.

Consider the consequences. If you don’t plan to unlock your phone at a border officer’s “request,” how prepared are you for potential issues (refused entry, detention, missing your connection)? Decide in advance.

If you care about your privacy, decide in advance what kinds of information you want to protect. Photos? There have been more than a few cases where people received real prison terms over baby-bath photos or videos. Social media posts? Border officers will likely be interested only to confirm you’re not a terrorist or a drug trafficker. Search and browsing history? Personally, I wouldn’t want anyone getting access to that. What about passwords? Are you okay with all the usernames and passwords your browser has saved being stored who-knows-where indefinitely, used by who-knows-who for who-knows-what? And don’t forget location history, call logs, messages and contacts, plus access to photos and documents synced with your home computer via OneDrive, Dropbox, or Google Drive.

Give employer data its own section, especially if the company has specific security requirements. Security policies pushed to the device via Exchange or other MDM systems can help here.

Once you’ve decided exactly what you’re going to protect, you can move on to the actual technical measures.

Technical defenses

Before we dive into technical protection methods, let’s start with the basics of how the device works. And even if you’re on Android, don’t skip the iPhone section — it covers many fundamentals that apply to both platforms.

Securing your iPhone

Overall, it’s easier to secure an iPhone than an Android device. But let’s take it step by step.

Have you settled on a strategy yet? If you’re ready to go all-in on protecting your data, you’ve got a few options.

First, set a long passcode (six digits or, better, an alphanumeric code), then power the phone off. Without that code, getting in is effectively impossible. But if your iPhone has a fingerprint sensor and you forget to power it down before crossing a border, a border agent can simply order you to place your finger on the scanner to unlock it. Biometric unlocks typically don’t require warrants or special authorization from law enforcement. So: turn the phone off.

Overzealous Border Agents

A fair question: what’s to stop border agents from holding you until you disclose (or enter) your device passcode? On the face of it, not much: in a well-known case, a NASA employee—an American citizen, incidentally—was detained and “pressured” (their word) until he gave up his phone’s PIN. That said, such incidents are extremely rare—the exception rather than the rule. And U.S. law today has a broad gray area: border officers have sweeping powers, but they’re supposed to use them only when they have “reasonable suspicion.”

A border officer may “ask” you to unlock your phone with a passcode. If it’s just a request (in official terminology), you have the right to politely refuse. They won’t detain you for that—though there may be other consequences, as we’ve discussed. If it’s an order, you don’t have a choice. But an officer can only order you to enter or disclose your passcode if they have “reasonable suspicion,” and only in exceptional cases. At the same time, both border officers and police can, in practice (this is another gray area), compel you to unlock with your fingerprint on the spot. In short, don’t lie, and resisting won’t help either. So what’s left?

Second, before your trip you can factory-reset the device and set it up from scratch with a fresh Apple ID. That’s a device you won’t mind showing a border officer. After crossing the border, just connect to Wi‑Fi, reset the phone again, and restore from a cloud backup (obviously, you need to have such a backup to begin with, and the wireless connection must be fast, stable, and capable of transferring several gigabytes of data). Note an important point about two‑factor authentication: to sign back into your Apple ID, you’ll need to have your second factor with you (for example, a SIM card with a trusted phone number that can receive the one‑time SMS code). If you don’t plan for this in advance, you could lock yourself out of your own account and iCloud data.

If you’re taking your computer with you, you can create the backup locally in a hidden container using the TrueCrypt format or one of its successors. You can safely present the outer container for inspection and even disclose its password—the existence of a hidden volume cannot be proven. That said, nested encrypted volumes deserve a separate discussion; we won’t dive into that here. (Don’t forget the backup password!)

If you don’t want to take a hard line or wipe your phone over a negligible 0.08% chance of it being searched, consider other options.

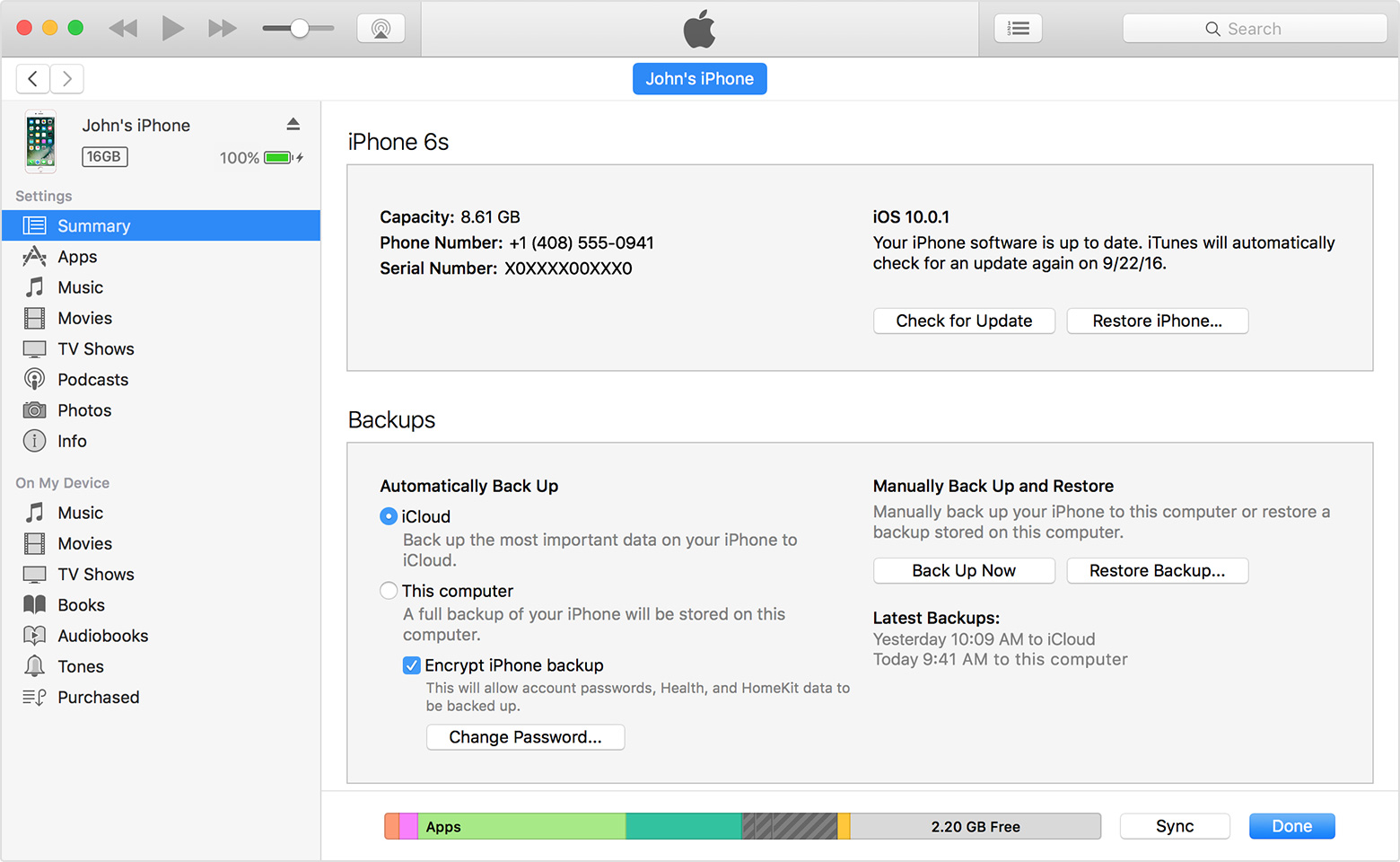

If you have an iPhone running the latest iOS and you haven’t jailbroken it, you’re in luck: extracting a full physical image of the device isn’t possible. The only analysis option available to border agents—aside from manually launching apps on the phone—is to create a backup via iTunes or a specialized tool (Elcomsoft iOS Forensic Toolkit or similar). Countering this is also very easy: just make sure you’ve set a password for backups in advance. To do this, open iTunes and enable the “Encrypt iPhone backup” option:

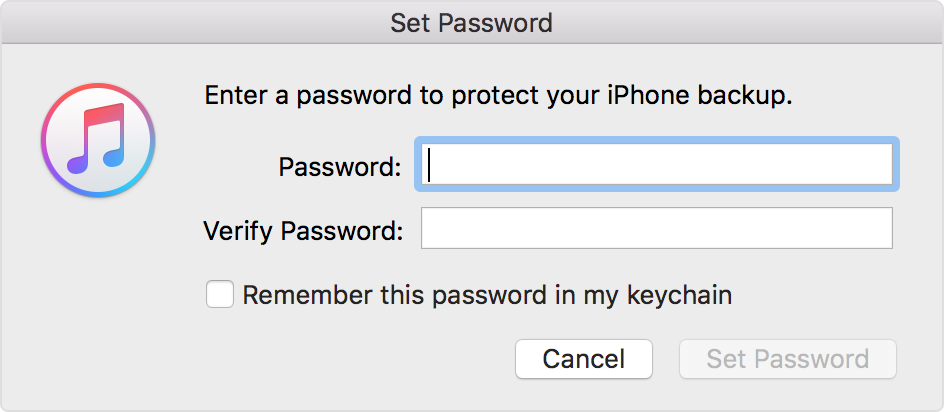

Next, you’ll need to enter the password:

What should you use as the password? We recommend generating a long, random password of 10–12 characters that includes letters (both upper and lower case), numbers, and special characters. Generate it, print it on paper, and set it on your phone. Keep the paper at home; don’t carry it with you. If someone asks you for the backup password, explain that you don’t use offline backups, so for security you chose a long, random password that wasn’t meant to be memorized. Since you don’t need this password in everyday use, that’s a perfectly plausible scenario.

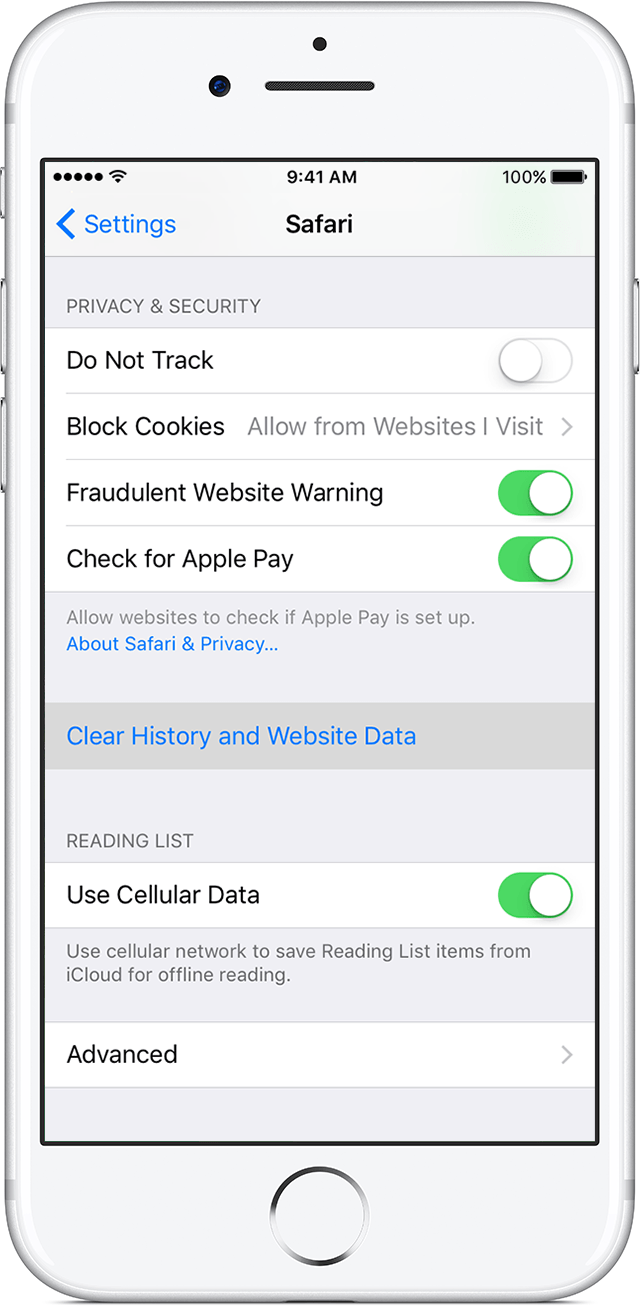

Want to protect your passwords? Turn off Keychain and iCloud Keychain on your phone (https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT204085). The passwords will be removed from the device and won’t sync back from iCloud until you explicitly re-enable iCloud Keychain. Similarly, you can delete your browsing and search history (https://support.apple.com/en-us/HT201265):

Until recently, these steps wouldn’t have fully protected you, because Apple kept deleted browser history on its servers for an unspecified length of time. After Elcomsoft released a tool that could recover those deleted entries, Apple took notice and closed the loophole.

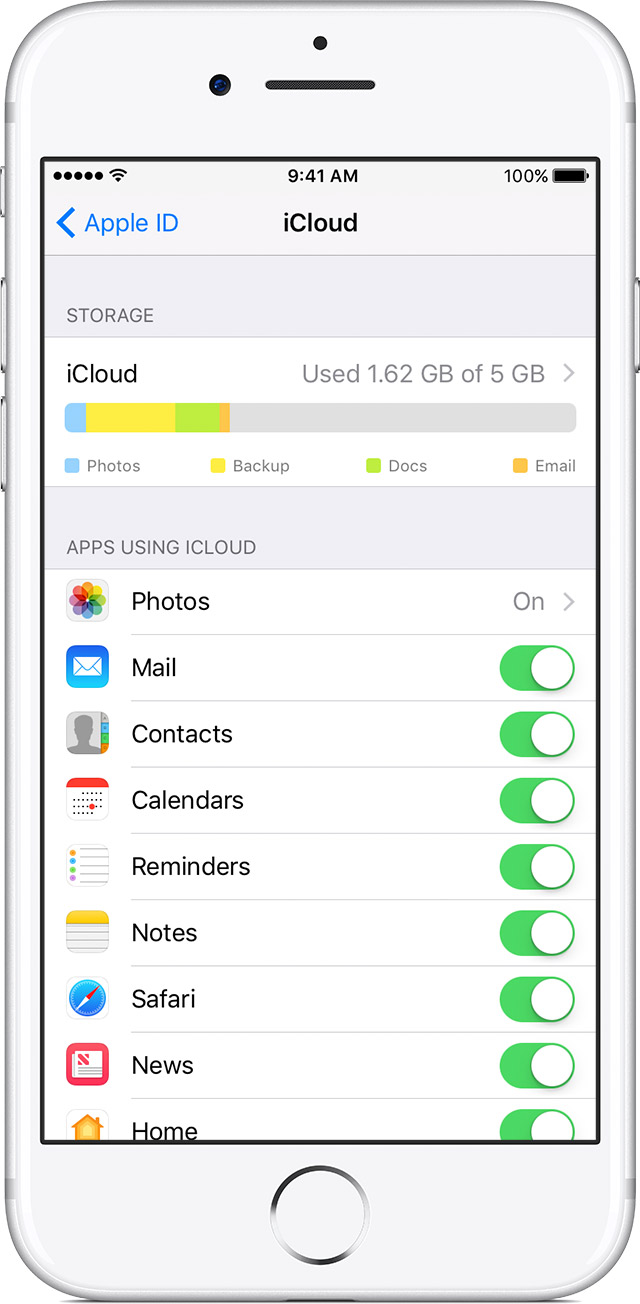

Still, your browser history will remain in iCloud for at least two weeks after you delete it. To tie up the loose ends for good, you’ll need to turn off iCloud data sync (you can always turn it back on after you cross the border). How to do this is covered in the official KB:

Your device’s backups may also live in the cloud. That said, access to cloud data is governed by different laws, and border inspections currently don’t pull data from cloud backups. If it helps you sleep better, you can disable cloud backups and delete existing ones, but there’s little practical benefit in doing so.

Finally, you can turn iCloud off entirely. That said, we don’t recommend it—at a minimum, disabling iCloud means you lose theft protection features like Activation Lock and Find My.

Securing Android

As you may recall from the major article published in the previous issue, we concluded that among mainstream systems, Android is the least secure. Accordingly, if your smartphone runs Android, you’ll need to put in some serious work to protect it.

The first and most important thing is protection against physical data extraction. A border officer has the legal right to inspect any item in your luggage or personal belongings. If they get hold of an Android phone, they can simply use a service mode (EDL, Qualcomm’s 9006/9008 modes, LG UP for LG devices, and so on) to access the data. And here’s the kicker: in 85% of cases that will be enough. According to recent figures, only about 15% of Android devices use encryption for the data partition.

If you’re thinking there won’t be a qualified specialist at the border to pull data from your device, I’ve got bad news: modern tools make it so easy even a janitor could do it. Animated, step-by-step prompts with pictures show exactly what to tap on your phone and where to plug in the cable, right on the computer screen. They can also just confiscate your device (there have been cases) and extract the data later in a relaxed setting. The moral? Turn on encryption already.

Android offers several convenience unlock methods under the Smart Lock umbrella, many of which are insecure. For example, if you use a fitness tracker or smartwatch and have set your phone to unlock whenever it’s connected over Bluetooth, stop right there. There’s also nothing to prevent a border agent from simply holding a photo of your face up to the camera (another strike against Smart Lock). On many devices, fingerprint unlock reliability is questionable as well. Bottom line: disable Smart Lock and make sure your phone can be unlocked only with a PIN—preferably a long, hard-to-guess one.

Unlike iOS, where almost everything ends up in the backup and you can protect the backup with a password once and for all, Android backups are created either in the cloud or via ADB. They include a fairly limited set of data, and you can’t encrypt them. That said, authentication tokens from many popular messengers and social networks do make it into backups, so keep that in mind. Creating an Android backup is very simple: unlock the phone, enable Developer Options, connect it to a computer, and run the command. If someone persuades you to unlock your phone, this is most likely the procedure they’ll use.

If someone pulls an ADB backup from your phone, it could include:

- Wi‑Fi network passwords and system settings;

- Photos, videos, and the contents of internal storage;

- Installed applications (APK files);

- Data from backup‑enabled apps (including authentication tokens).

Among other things, on Android smartphones Google is king. Google collects a huge amount of data that gets sent straight to its servers. If you’re ordered to hand over your account password and a border agent manages to log in (say, because you still haven’t enabled two‑factor authentication), they won’t even need your phone: your Google account contains just about everything—and then some. What can you do? Remove your Google account from the phone before boarding and sign in with a newly created one. Fortunately, unlike on an iPhone, you don’t have to wipe the device to do this. And don’t forget to clear app data—at a minimum Contacts, Photos, Google Maps, and Chrome’s browsing data. Traces will probably remain, but if the device doesn’t raise suspicion, there may be no deeper inspection.

What about photos? If you need access to your photo and video library while traveling but don’t want to keep them on the device itself, you can use the cloud again (hint: you can even remove the Dropbox app from your phone) or a hidden nested container on your computer. Finally, you can store photos in Google Photos under the account you planned to remove from your phone before the trip—just keep in mind that by default it uploads reduced, “optimized” versions.

Finally, if you have a custom recovery (TWRP), you can create an encrypted backup of the data partition and store it in a nested container on your computer. Restoring it later takes just a few minutes. That said, crossing the border with a “bare,” unconfigured device is a bad idea—you’ll look very suspicious to a border officer.

Editor’s Note

Paradoxically, a smartphone with encryption turned off can make crossing borders much easier. The thing is, modern phones that ship with Android 6.0+ are required to encrypt user data and often store the encryption key in a hardware module known as the TEE (Trusted Execution Environment). That’s good for security, but it also gets in the way of creating or restoring a full system backup with TWRP.

But if encryption is off and you’re able to make backups, you can easily outsmart whoever’s inspecting your device. Here’s the idea: install the TWRP custom recovery on your smartphone, reboot into it, make a nandroid backup of the system and data partitions (that’s the OS and your apps/data), pull the backup off the phone (it’s stored in the TWRP folder on the SD card), and stash it somewhere like Dropbox. Then factory-reset the phone, sign it in to a burner account, install a few apps, type a couple of unimportant passwords in the browser — basically, make it look like an actively used device. After that, reboot into TWRP again, make another backup, and upload that one to the cloud too.

You’ll end up with two backups: one of your primary system and one of a decoy system. All you need to do is restore the second, fake backup before your trip, cross the border, and then restore the main one. All your settings, software, and everything else—right down to the arrangement of icons on your desktop—will be preserved exactly as before.

Legal countermeasures

As of today, a U.S. border officer can ask an applicant for admission to unlock a device and hand it over for inspection. In some cases (reasonable suspicion, placement on a watchlist of potentially dangerous or inadmissible persons), the officer can require you to unlock it. The difference between a request and a demand can be hard to spot for a tired traveler rushing to make a connection, but it does exist. Ignoring a lawful order isn’t an option and can have unpleasant consequences. A request, however, can be politely declined; if you can articulate reasons for refusing, even better. Yes, you may be denied entry, and yes, you may be detained for an indeterminate time, but under U.S. law you haven’t committed a crime.

Conclusion

Your smartphone is a personal device that’s always with you. It knows things about you that even you might not realize. Letting outsiders in is a great way to earn yourself a lingering headache, stoke your paranoia, or run into legal trouble. We firmly believe the right to privacy should remain inviolable and be breached only in exceptional cases and only by court order. A business or tourist trip abroad doesn’t qualify. Protecting your private life by legal means is your full and inalienable right—but no one will exercise it for you. If you don’t want strangers prying into your personal life, you’ll need to understand the laws and use the legal tools available to keep them out.

Keep in mind that border officers have, if not the law, then the latitude to interpret it in their favor—plus brute force and coercive tactics—and they’re not shy about using them. The use of coercion has been growing year over year. For your own safety, it’s unwise to argue with border officials. Don’t lie, scheme, or try to wriggle out of it; that will only make an already tense situation more complicated. It’s far more effective to rely on a set of technical protective measures, which we describe in this article. Remember: no one can extract data from a phone that isn’t physically on it, but any password can be compelled from you if they’re determined enough.