Why you can’t just install an app

On modern mobile platforms, only digitally signed code can run. On Android, you can install an app package signed with a regular (even self-signed) certificate. On iOS, it’s more complicated: the package is signed at installation time, and the device-specific signature allows it to run only on the device it was created for.

Add to that the fact that Apple is the sole authority that issues—and can revoke—code-signing certificates, and you get a situation where no unsigned code (or code signed with an untrusted certificate) can run on the device.

The Official Route: a Developer Account

The simplest—and frankly the only above-board—way to solve this problem is the official one. If you really want to, you can install apps outside the App Store, but the process is convoluted and essentially out of reach for the average user.

One option is to use enterprise and custom distribution. With enterprise distribution, the organization—such as an educational institution or a large company (e.g., in transportation)—registers an enterprise account, enabling it to sign app packages in-house and deploy them to corporate devices via MDM (Mobile Device Management).

An enterprise signing certificate is used. It typically has a one‑year validity period, but there’s no limit on how many apps it can sign. On the first launch of an app signed with such a certificate, if the device hasn’t been preconfigured by the owning company, the user will need to go into Settings and add the certificate to the trusted list. At that point, the device will contact Apple’s servers, which will either grant (or deny—details below) permission for this action.

What’s the catch? There are several. First, only organizations—not individuals—can participate in the corporate distribution program. Second, participation is paid. Finally, you’re still under Apple’s control; the company still decides whether an app is allowed to run on a specific device. If Apple believes an enterprise certificate issued to an organization is being used in violation of the license agreement, that certificate will be revoked immediately, and you won’t be able to sign newly installed apps with it. Such certificates regularly «leak» and are used by various «alternative app stores» for signing apps.

A variation on the same theme is the special distribution option for members of the Apple Developer Program (Ad Hoc). Its primary purpose is to let developers test their own apps on their own devices, so it requires an Apple Developer Account. With this distribution you can do bulk provisioning: the same build can be signed for up to a hundred devices at once.

This approach has both clear benefits and drawbacks when compared to a corporate distribution model.

On the plus side, the app is easy to install and launch; there’s no need to approve a certificate, and you don’t have to contact Apple’s servers each time you install it. As a result, you can install the app on an iPhone with no network connection—entirely offline.

The second advantage of this approach is its accessibility for everyday users. For just $99 per year, you can register your own developer account, which lets you install any apps on up to 100 devices.

Hold on—are we sure that’s really a “benefit”? Ninety-nine dollars a year isn’t exactly cheap just for the privilege of installing your own apps on your own iPhone, and the 100-device limit is per year: removing a previously registered device from your account doesn’t free up one of those 100 slots.

Another downside of the official approach is that distribution is tightly tied to Xcode, which in turn requires a Mac running macOS. That makes it more complicated and expensive if you don’t already have a Mac.

Finally, one more drawback of this approach: getting an individual developer account isn’t straightforward because of the hoops Apple puts in place. Forget about using throwaway Apple IDs—Apple verifies your details and can reject your application without explanation. Our developers report better odds if you use an older Apple ID with a real address on file (ideally the same one linked to your payment card); applying from a Mac helps, and having a purchase history on that account improves your chances further. Even so, there’s no guarantee your Developer Program enrollment will be approved; rejections typically come without any stated reason.

At this point, the official methods end and the semi-official ones begin.

Semi‑official method: Cydia Impactor

A semi-official approach is to use the same official developer account, but sign the package with the Cydia Impactor app instead of Xcode. Why is this better than Xcode? Mainly, it’s simpler. Xcode makes you fill out a bunch of fields, create a provisioning profile, and export a certificate—a convoluted process even for seasoned developers. Cydia Impactor lets you just sideload the app to your iPhone, requiring only your developer account username and password.

Second, unlike Xcode and many alternative solutions, Cydia Impactor is available on multiple platforms, including macOS, Windows, and Linux.

The only drawback: you need an Apple ID that’s enrolled in the Apple Developer Program. If you have one, the process is fairly simple, but you should prepare by creating an app-specific password in your Apple ID account.

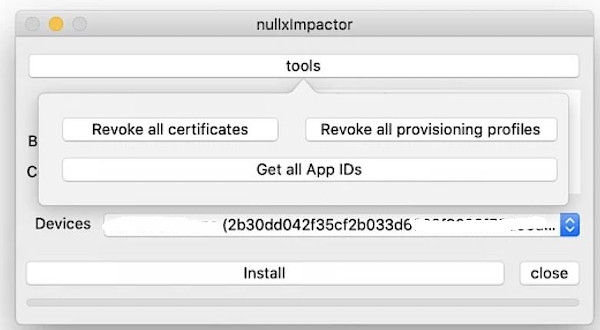

Here’s the method for installing an app using a developer account and Cydia Impactor:

- Connect the iPhone to your computer and establish a trusted connection (tap “Trust This Computer?” on the iPhone and enter the device passcode).

- Launch Cydia Impactor.

- Drag the app’s IPA file onto the Cydia Impactor window.

- Enter your Apple ID login and an app-specific password (the Apple ID must be enrolled in the Apple Developer Program).

- If your Apple ID belongs to more than one developer team, select the appropriate one.

- Confirm the prompt; Cydia Impactor will sign the IPA and install it on the device.

- That’s it—the app is ready to use.

The approach is sound. Still, it would be nice to do the same using a standard Apple ID. Surprisingly, that’s possible—though with some limitations.

Into the gray area: signing apps with a regular Apple ID

So, you’ve decided to sign an app with a regular Apple ID that isn’t enrolled in the Apple Developer Program. Until 2019, this was a little-known but workable option with a few caveats: apps signed this way would only run for seven days, and you could have no more than three such personally signed apps installed on a single device. About three years ago, Apple moved to shut this down—though not entirely. The remaining loophole only works on macOS. So if you’ve got a Mac, you can try one of the following apps.

Nullximpactor

Nullximpactor is essentially an alternative to Cydia Impactor. It only works on macOS but lets you sign apps using regular (non‑developer) Apple IDs.

Developer @nullx recommends using throwaway Apple IDs without two-factor authentication for signing. Otherwise, you’ll need to create an app-specific password in your account.

Pros: Once it’s set up, it’s pretty easy to use.

Cons: macOS only; requires initial AltDeploy setup (guide); free Apple ID limits still apply (the app will run for no more than seven days, and you can have no more than three sideloaded apps).

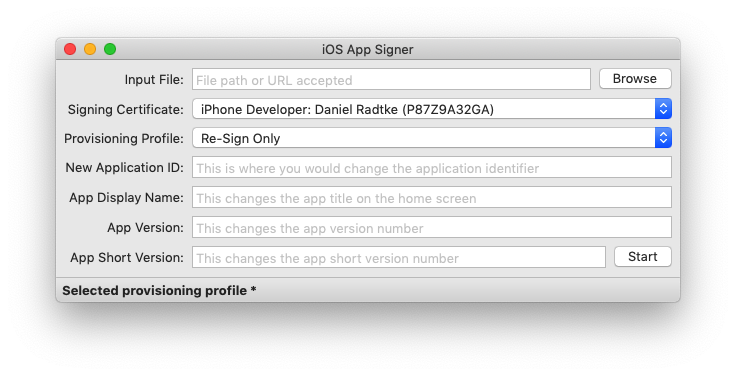

iOS App Signer

iOS App Signer is an interesting tool that takes a different approach from other utilities in this space. It uses Apple’s Xcode to sign apps while working around the need for a paid developer account. That said, the seven-day certificate limit and the cap on how many apps you can install this way still apply.

Using iOS App Signer can be tricky, but there are detailed instructions on GitHub.

Pros: An original method that doesn’t require installing AltDeploy.

Cons: macOS-only; requires Xcode; difficult to set up; personal account limitations.

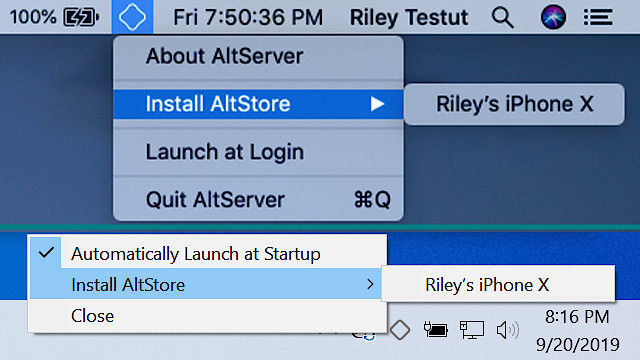

AltDeploy and AltStore

AltStore is a popular way to install unofficial apps and emulators on iOS devices without jailbreaking. You can find installation instructions on the project website.

Compared to the online app stores listed below, AltStore is a genuinely solid alternative. You can verify the origin of the IPA package yourself, and it will be signed with your own personal certificate—something Apple won’t suddenly revoke, which often happens with services like IPWind and the alternative app stores discussed below.

This approach has its share of drawbacks. First, you inherit all the limitations of personal signing certificates: no more than three sideloaded apps installed, and each build only runs for seven days. Second, you need to install and configure both iTunes (with Wi‑Fi sync enabled) and the AltServer component on your computer, which is used to automatically re-sign the installed apps every seven days.

Is it really worth the hassle of installing up to three third-party tools on your device? I strongly doubt it. But combined with a developer account, it can make sense for installing apps that aren’t—and won’t be—in the official App Store.

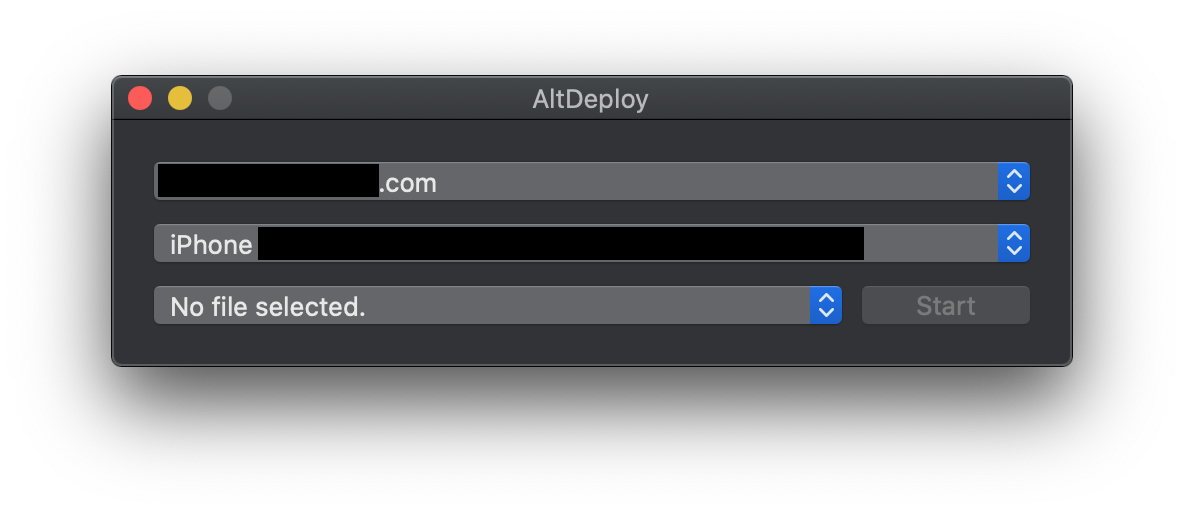

AltDeploy is essentially a fork of AltStore. Unlike AltStore, which you install directly on the iOS device, AltDeploy lets you install and sign apps from your computer. You’ll need a Mac running macOS and be prepared for the usual AltServer hurdles. Detailed installation instructions are available here.

Online signing

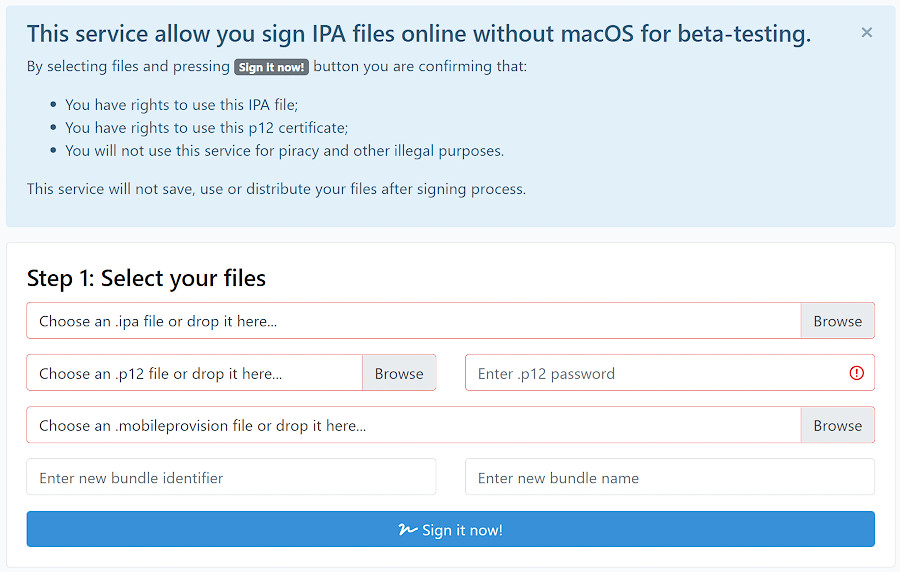

There are free services that let you sign an app package online, without connecting your device to a computer. One example is IPASign.

In addition to the IPA file itself, the service asks for a .p12 signing certificate, its password, and a provisioning profile. The service will generate a QR code that you can scan on an iPhone to install the signed IPA over the air, without connecting to a computer. If you’re planning to use your own certificate, think twice about trusting an anonymous service with it. However, if you’ve gotten your hands on a corporate certificate from a leak and want to test it, that’s another matter.

How is this implemented? Most likely there’s a macOS machine with Xcode running behind the scenes, with a web interface bolted on. The exact implementation details are unknown.

IPAWind is another service in this category. It lets you sign packages not only with your own certificate but also with theirs (the latter can be revoked at any time, but your account stays out of the line of fire). As a bonus, you can edit the manifest to install a duplicate of an app (for example, have two WhatsApp instances on an iPhone) and enable the iTunes File Sharing option, which makes the app’s documents accessible via iTunes.

Alternative App Stores

Up to this point, we’ve covered official ways to install an app on a device; at worst, we were edging into a gray area. The methods that follow explicitly violate Apple’s policies and, in some cases, may infringe the rights of other rights holders.

The first option is third‑party app stores. These solutions are generally easy to install and use (open the store’s page in Safari, tap a button, the alternative app store installs on your device, trust the certificate — and you’re good to go). There are both paid and free options. The most popular include:

- Ignition — focuses on jailbreak utilities, tweaks, and patched apps: https://app.ignition.fun/

- TweakBox — offers a catalog of utilities, emulators, jailbreaks, and more (catalog: https://sideload.tweakboxapp.com/): https://www.tweakboxapp.com/

- iPASTORE — a paid (subscription-based) third-party app store: https://ipastore.me/

Those three are far from the only ones. AppValley, CokernutX, Panda Helper, the paid AppDB, TweakDoor, Emus4u, iPABox, Zestia… Not all survived the iOS 14 rollout, but many are still working today.

All of these stores—including paid services—operate in violation of Apple’s policies: they misuse developer certificates and rely on leaked or deliberately purchased enterprise certificates and the corresponding distribution mechanisms. Apple routinely revokes such certificates, but the services always find replacements and re-sign both the store app itself and the tools installed through it. Here’s what the service itself says about this.

What risks come with using these services? A revoked Apple certificate can make the installed app impossible to launch. And because the service can technically modify (patch) apps on its side, there’s a chance the app you install will include an unwanted extra—potentially a malicious payload that, on older versions of iOS, could even compromise your device.

Whether to use such stores or not is up to you.

For jailbroken devices, several package managers are available: Cydia, Sileo, Zebra, Installer 5. Which one should you choose? Developers of jailbreak tools typically bundle their preferred manager, which will be installed on the device after the jailbreak. You can always install an additional manager alongside it.

On compromised devices, there are no restrictions tied to the use of personal profiles. You can install any number of apps, and there are no time limits.

TestFlight

TestFlight is a service for testing iOS apps, as well as a companion app that users can install on their devices. From a technical standpoint, TestFlight streamlines the distribution of test builds by simplifying the collection of device UDIDs and enabling delivery of builds to registered testers. You can’t use test builds indefinitely; sooner or later the certificate expires, and the user has to either update to the official release or install a fresh test build provided by the developer.

Both enterprise and individual developers can use TestFlight. For the latter, there’s a cap on the number of beta testers: no more than 100 UDIDs per year. Removing a UDID from the program doesn’t free up the slot.

Some developers use this service to distribute software that, for various reasons, isn’t accepted into the App Store. The most well-known example is Soap4me for iOS, which operates in a perpetual beta state. It’s a viable solution, but overly complicated for the average user.

Where to find app packages?

Probably the most well-known repository of IPA packages is iOS Ninja. From the site, you can download both app IPA packages and Apple firmware images for a range of devices (via direct links from Apple). Any IPAs you download will need to be signed before you can install them on an iPhone, using one of the methods described above.

Conclusion

“Pay up or suffer” is the takeaway here. Paying for the developer program lets you avoid shady (often not exactly free) services and the risks that come with them. That said, getting into Apple’s developer program isn’t guaranteed; lately it’s become tricky.

The free alternative—AltStore—takes serious effort to install and configure, and you’ll be constantly re-signing installed apps. To automate that, you need a companion server running on a computer at all times. Jailbreaking is a universal workaround, but it costs you one of iOS’s biggest advantages: timely, regular updates.

Which path to choose—and whether it’s worth the hassle—is, as always, up to you.