First, we’ll explore the theoretical aspects: how a connection works, how it is established, and how these mechanisms can be utilized. I will then demonstrate an example of a “poor” scanner implementation. After that, we’ll examine a well-designed scanner and create our own version.

Theory

Let’s start by examining how network devices typically interact with each other. They use sockets, which can be simply visualized as pipes. Each pipe has two ends, representing the sockets. One end of the pipe is on one computer, and the other is on another computer, allowing programs to send data through these “pipes” or read from them.

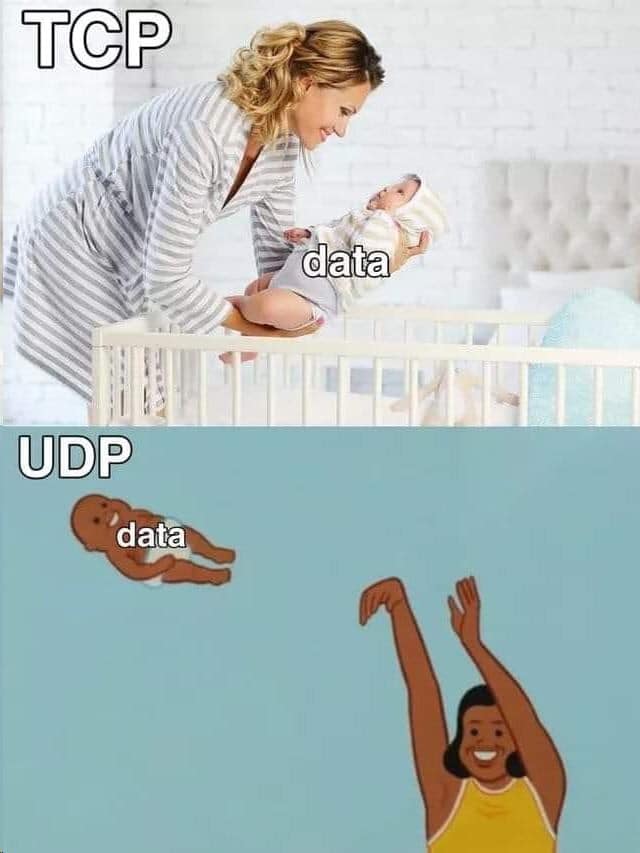

There are two types of sockets: TCP and UDP. They differ in what happens on the path from one end of the pipe to the other. A TCP socket ensures that packets are delivered to the other end of the pipe in the correct order and without loss—if it’s possible at all, of course. UDP sockets, on the other hand, prioritize speed and may lose or mix up packets along the way.

Video conferencing, for instance, effectively takes advantage of UDP. If something goes wrong with the connection, some packets may simply get lost, but the remaining ones will arrive on time, ensuring that you still get a picture, even if it’s not perfect.

Writing a Socket-Based Scanner

This scanner is the simplest and most straightforward. To find out which ports are open, you can try connecting to them one by one and see the results.

All code examples are presented in Python 3.10, and I prefer working in PyCharm, though I’m not insisting you do the same.

Let’s create a program and import the essential modules:

import socketfrom datetime import datetimeimport sys

www

You can learn more about working with the socket module in the official documentation.

Let’s note down the program’s start time—it will come in handy later for determining the scan duration.

start = datetime.now()We’ll store the pairs of ports and service names directly in the code. If you wish, you can upgrade this method, for instance, by using JSON files.

ports = { 20: "FTP-DATA", 21: "FTP", 22: "SSH", 23: "Telnet", 25: "SMTP", 43: "WHOIS", 53: "DNS", 80: "http", 115: "SFTP", 123: "NTP", 143: "IMAP", 161: "SNMP", 179: "BGP", 443: "HTTPS", 445: "MICROSOFT-DS", 514: "SYSLOG", 515: "PRINTER", 993: "IMAPS", 995: "POP3S", 1080: "SOCKS", 1194: "OpenVPN", 1433: "SQL Server", 1723: "PPTP", 3128: "HTTP", 3268: "LDAP", 3306: "MySQL", 3389: "RDP", 5432: "PostgreSQL", 5900: "VNC", 8080: "Tomcat", 10000: "Webmin" }We will convert the given argument into an IP address. To do this, we’ll pass the first command-line argument of our scanner to the function socket.—as a bonus, if a domain name is provided instead of an IP address, we’ll also get DNS resolution.

host_name = sys.argv[1]ip = socket.gethostbyname(host_name)Now, we’ll iterate through all the ports in the list and check if we can connect to them. If a port is closed, an exception will be triggered, which we’ll catch to prevent the program from crashing.

At the end of the process, save the end time and display the scan duration on the screen.

for port in ports: cont = socket.socket() cont.settimeout(1) try: cont.connect((ip, port)) except socket.error: pass else: print(f"{socket.gethostbyname(ip)}:{str(port)} is open/{ports[port]}") cont.close()ends = datetime.now()print("<Time:{}>".format(ends - start))input("Press Enter to the exit....")Now, to test our scanner, open the terminal, navigate to the directory containing the scanner, and execute the command.

python.exe socket.py 45.33.32.156

info

If you’re working on Linux, use the python3 command to avoid accidentally launching an outdated version of Python.

Of course, you can replace the IP address in the example with any host.

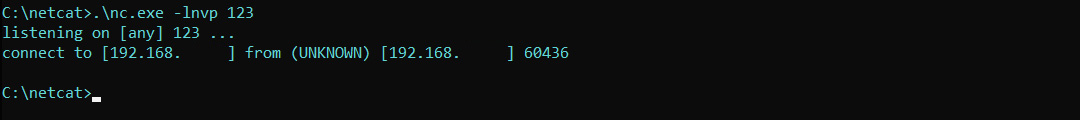

Let’s take a look at how this appears from the server’s perspective. For this, we’ll use the tried and true Netcat. Download it and run it as follows:

ncat.exe -lnvp 123

warning

You might need to whitelist Netcat in your antivirus software or coordinate its installation with your corporate security team. Hackers often use Netcat to establish shells on compromised systems, so any alerts from your antivirus are well-justified.

In a separate terminal, we initiate our scanner to analyze our own IP address. You can find your IP address by using the ipconfig / command. As a result, the Netcat window will display the following.

The screenshot shows that a full connection was established, and naturally, any program would also detect this in reality. So, it’s not possible to scan someone in this way without being noticed.

Let’s also scan the server scanme. (this is the IP address used in the first example). The results will look something like this:

Address: 45.33.32.156

45.33.32.156:22 is open/SSH

45.33.32.156:80 is open/http

The scanner identified two open ports—22 and 80. However, if you scan the same host using Nmap, you’ll see that there are many more open ports.

Nmap scan report for scanme.nmap.org (45.33.32.156)

Host is up (0.22s latency).

Not shown: 994 closed ports

PORT STATE SERVICE

22/tcp open ssh

80/tcp open http

1720/tcp open h323q931

5060/tcp open sip

9929/tcp open nping-echo

31337/tcp open Elite

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 5.02 seconds

Why is that? Nmap scans a significantly larger list of ports compared to our scanner, which allows it to detect more. If we include these ports in our scanner, it will also find them.

It’s clear that such a scanner is unlikely to be used in real-world scenarios, except for some very unusual cases: for instance, when you need to run a scan on a machine where installing a full-fledged scanner is impossible, but Python is already available.

Let’s try to create a scanner that’s less detectable and operates much faster.

Optimizations

To make our scanner more efficient and stealthy, we should avoid establishing connections, as this requires a three-way handshake involving three packets and additional time to close the connection. But how can we determine if a port is open without attempting to connect?

It turns out there’s a method to achieve this. It involves not necessarily completing all three steps of the handshake. If the handshake isn’t completed, the connection isn’t established, meaning it doesn’t need to be closed either. You can tell if a port is open from the response to the very first packet sent to the server. By deliberately creating an incomplete handshake, you save time. Additionally, there’s a bonus: if the connection isn’t established, programs on the target machine won’t detect the scan.

How does the three-way handshake work? Initially, the connection initiator sends a packet with the SYN flag to the target machine on the desired port. If the port is open, a response with the SYN and ACK flags should be received. If the port is closed, the behavior may vary, but typically the response should include a RST flag.

If the initiator still intends to establish the connection, they must send another packet, this time only with the ACK flag, after which the connection will be considered established.

The key point here is that sending the final ACK is not necessary, as we determine the port status after the second packet. Sending the third would waste valuable time and compromise stealth.

To close a connection, a packet with FIN and ACK flags must be sent. This information won’t be necessary for us today; it’s only for gaining a more complete understanding of what happens with a TCP connection at various stages of its lifecycle.

Creating a SYN Scanner in Python

Let’s create a new Python script and import the necessary modules:

from scapy.layers.inet import ICMP, IP, TCP, sr1import socketfrom datetime import datetimeIf you encounter the error ModuleNotFoundError: , it means you need to install the scapy module from PyPI by running: pip .

Before scanning, it’s a good idea to check if the target machine is accessible. You can do this by sending an ICMP Echo Request, commonly known as a ping:

start = datetime.now()# Here we check if the server is onlinedef icmp_probe(ip): icmp_packet = IP(dst=ip) / ICMP() # Sending and receiving a single packet resp_packet = sr1(icmp_packet, timeout=10) return resp_packet is not NoneNow let’s write the scanning function itself. It will iterate over all ports, send SYN packets, and wait for a response.

def syn_scan(ip, ports): # Iterate over each port for port in ports: # The S flag indicates a SYN packet syn_packet = IP(dst=ip) / TCP(dport=port, flags="S") # The packet waiting time can be set as desired resp_packet = sr1(syn_packet, timeout=10) if resp_packet is not None: if resp_packet.getlayer('TCP').flags & 0x12 != 0: print(f"{ip}:{port} is open/{resp_packet.sprintf('%TCP.sport%')}")ends = datetime.now()A port is considered open if the response packet has the SYN and ACK flags set (or at least one of them).

This time, instead of creating our own list to determine which service corresponds to which port, we’ll use an existing one provided by Scapy. You can use the resp_packet. function, which displays the service associated with the target port.

###[ IP ]###version = 4ihl = 5tos = 0x0len = 44id = 0flags = DFfrag = 0ttl = 57proto = tcpchksum = 0x71c4src = target_ipdst = attacker_ip\options \

###[ TCP ]###sport = sshdport = ftp_dataseq = 986259409ack = 1dataofs = 6reserved = 0flags = SAwindow = 65535chksum = 0x6d61urgptr = 0options = [('MSS', 1436)]We’re almost there: we just need to feed the function a list of ports to check and implement input for target information. This task will be handled by the main function. This time, we will create an interactive input for the target address and perform a preliminary check of the target’s availability before scanning.

if __name__ == "__main__": name = input("Hostname / IP Address: ") # Identify the target IP ip = socket.gethostbyname(name) # Set ports for scanning ports = [20, 21, 22, 23, 25, 43, 53, 80, 115, 123, 143, 161, 179, 443, 445, 514, 515, 993, 995, 1080, 1194, 1433, 1723, 3128, 3268, 3306, 3389, 5432, 5060, 5900, 8080, 10000] # Catch exceptions when the tuple ends try: # If unable to connect to the server, output an error if icmp_probe(ip): syn_ack_packet = syn_scan(ip, ports) syn_ack_packet.show() else: print("Failed to send ICMP packet") except AttributeError: print("Scan completed!") print("<Time:{}>".format(ends - start))In the array ports, you need to list the ports you plan to scan. It’s not necessary to go through all of them: even Nmap by default only scans the top 1,000 most popular ports, while the rest can be overlooked unless a full scan (-p-) is explicitly requested.

In the final iteration of the loop, an error occurs (the array ends), so this event can be used to indicate the completion of the process.

Since we now request the address directly within the script, it can be run without any parameters.

python.exe synscaner.py

If you open Netcat again and scan it, the scanner will show an open port, but no connection will be established. The stealth check is successful!

www

You can find the complete code in my GitHub repository. It also includes some enhancements not covered in the article, such as a graphical interface built with PyQt.

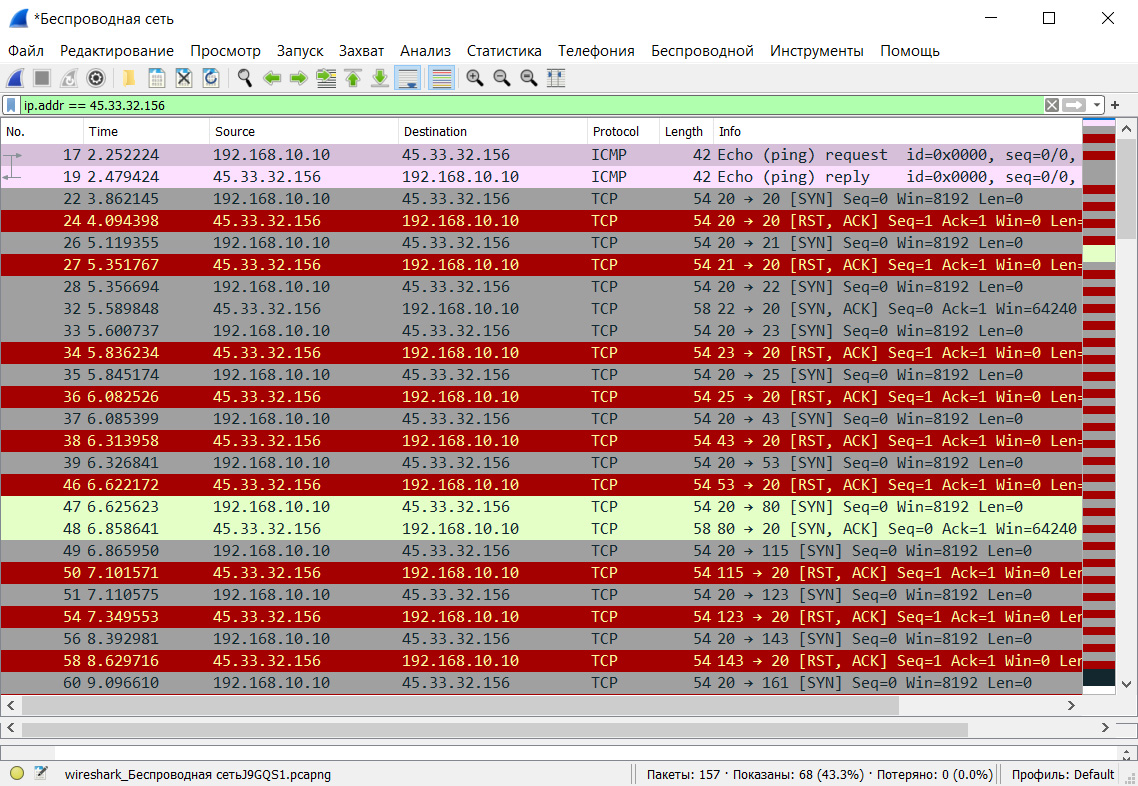

Let’s scan a public server (such as scanme.) and use Wireshark to observe the network packets. Start Wireshark first, then proceed with the scanning.

To avoid getting overwhelmed by the flow of information that Wireshark outputs, let’s apply a filter. We’ll show only the packets that are sent to or received from the host with the IP address 45.33.32.156.

ip.addr == 45.33.32.156

After applying the filter, the Wireshark window appears as follows.

First on the list is an ICMP packet (ping), which was sent to check availability. Next are packets with RST/ACK flags (closed ports) and SYN/ACK flags (open ports).

Conclusion

Today we explored two scanning methods: with and without establishing a connection. We didn’t cover UDP port scanning in this article because it is much more complex and less frequently needed. Nevertheless, Scapy can facilitate this if you ever find yourself in need. Remember, these kinds of programs are primarily for gaining experience, not a substitute for ready-made tools. It’s the understanding of how everything works inside that makes you a true hacker!