The first part of this article discusses attacks targeting access points; while the second part, attacks targeting clients. Imagine a situation: a hacker failed to penetrate into your infrastructure from the Internet, couldn’t develop any attacks internally at the network level, and was unable to capture Active Directory. But this doesn’t mean that you can relax and rest on laurels: if attackers are located within the wireless network coverage zone, they can deliver a physical attack. Wireless networks are the first barrier encountered by an external intruder who hasn’t yet implemented other techniques, but got up close to your office. Don’t underestimate this attack surface: it’s much more promising for a motivated external attacker than a well-protected perimeter on the Internet.

In information security, wireless network protection is usually limited to recommendations on secure Wi-Fi configurations; while wireless attacks are believed to be quite silent. Certain wireless IDS solutions exist, but most of them remain academic experiments. The situation is quite paradoxical; there are two perimeters: one in the digital space protected by all sorts of WAFs, SOCs, and other IDS/IPS; and the other one in the real world — wireless networks whose coverage zones in most cases reach beyond the controlled area and aren’t properly protected.

Listening to the airwaves enables you to sense ‘subtle’ energies and detect all relevant Wi-Fi attacks. All you need is an ordinary Wi-Fi network card and the monitor mode recording every wireless packet on the air. When you finish reading this article, you will be able to create a wireless antivirus (wireless IDS).

Just imagine the shock experienced by an attacker who fails to penetrate your perimeter through wireless networks and gets caught while trying to deliver an attack.

Deauthentication

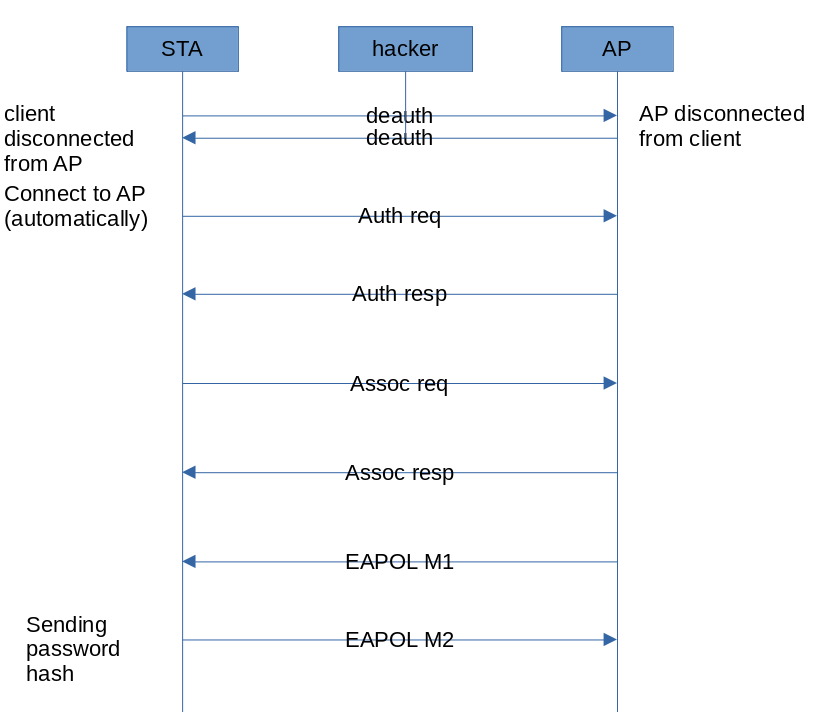

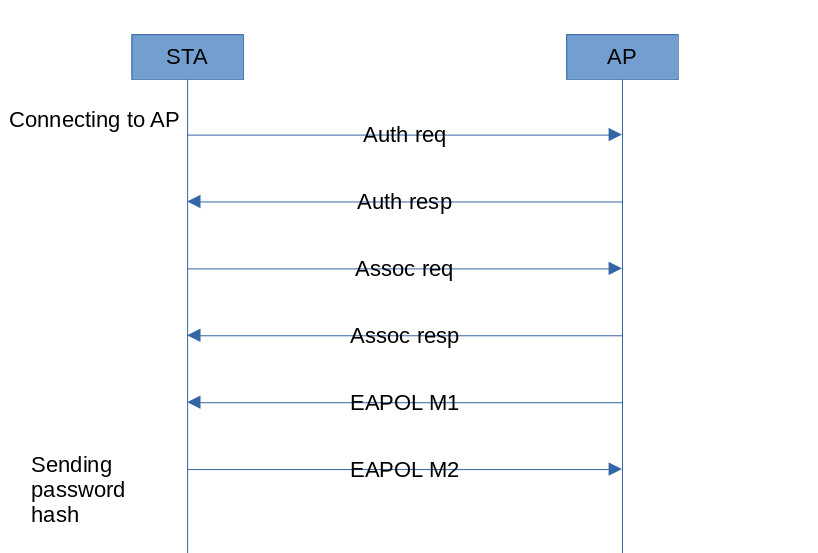

Let’s start with the most common and simple attack known to all hackers: deauthentication. The attack is delivered against WPA PSK networks (most widespread ones nowadays) and involves simultaneous disconnection of the access point and clients from each other. To achieve this, the attacker sends special packets in both directions on behalf of both the access point and clients. As a result, the client, who, in fact, didn’t intend to disconnect from the access point, resends the password hash (i.e. handshake) in the second EAPOL message.

For a hacker, a handshake is of utmost interest because it makes it possible to deliver a wordlist-based password guessing attack at a great speed (millions of hashes per second).

Deauthentication attacks aren’t absolutely silent: clients are annoyed when such an attack occurs. Wireless network users lose their connections. However, not all of them realize that this was an attack, especially taking that disconnection can last for an extremely short time. Most probably, complaints about problems with Wi-Fi (if any) would be submitted to the operations department rather than to the security department. However, by monitoring the airwaves, you can easily detect such attacks because deauthentication packets are sent from both parties at once:

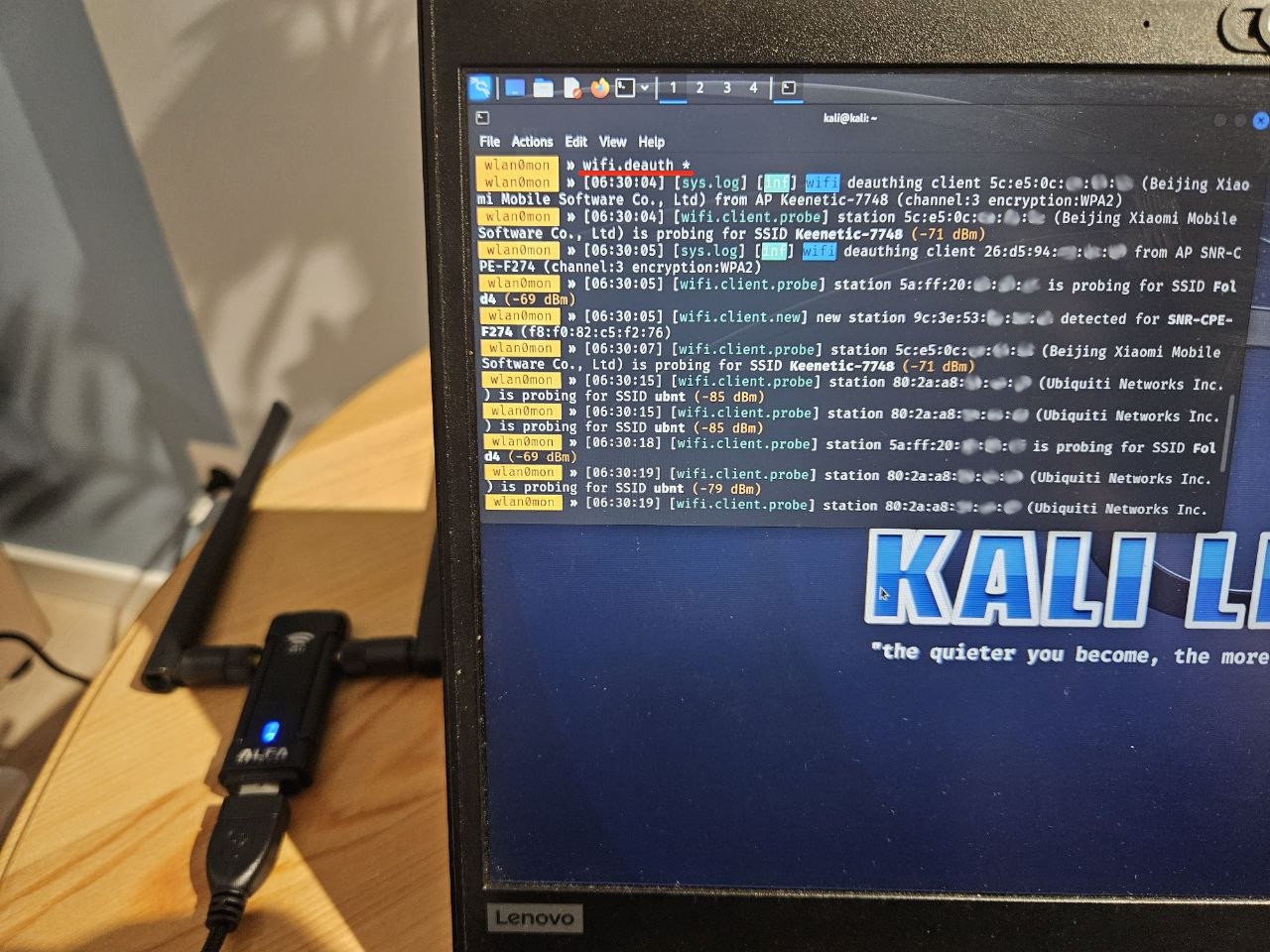

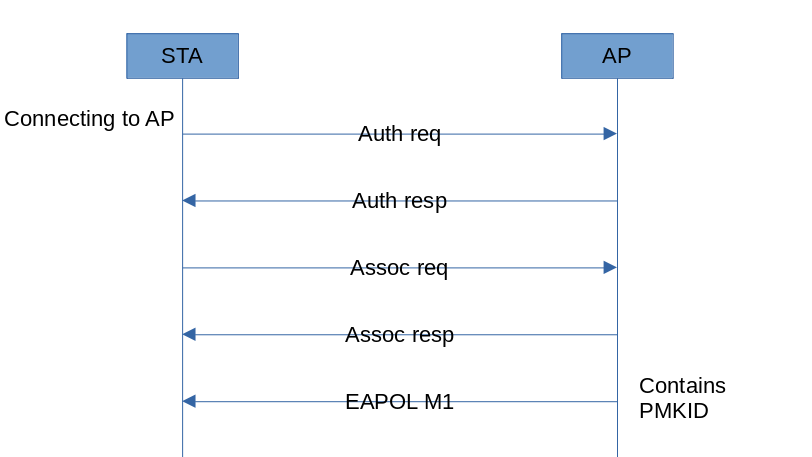

defence/wifi/deauth.py#!/usr/bin/python3from scapy.all import *from sys import argvfrom os import systemiface = argv[1]conf.verb = 0alerts = []def alert(src, dst, signal, essid): if src in alerts and dst in alerts: return print(f'[!] WPA handshake deauth detected: "{essid}" {src} <-x-> {dst} {signal}dBm') system("zenity --warning --title='PMKID gathering detected' --text='WPA handshake deauth detected' &") #system("echo 'WPA handshake deauth detected' | festival --tts --language english") alerts.append(src) alerts.append(dst)aps = {}deauths = {}def parse_raw_80211(p): signal = int(p[RadioTap].dBm_AntSignal or 0) if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "dBm_AntSignal") else 0 freq = p[RadioTap].ChannelFrequency if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "ChannelFrequency") else 0 if Dot11Beacon in p: # Beacon ap = p[Dot11].addr2 essid = str(p[Dot11Elt].info, "utf-8") if not ap in aps: aps[ap] = {"essid": essid} if Dot11Deauth in p: ap = p[Dot11].addr3 src = p[Dot11].addr2 dst = p[Dot11].addr1 if ap == src: print(f"[*] deauth {src} -> {dst}") elif ap == dst: print(f"[*] deauth {dst} <- {src}") deauths[src] = dst if deauths.get(dst) == src: alert(src, dst, signal, aps.get(ap,{}).get("essid"))sniff(iface=iface, prn=parse_raw_80211, store=0)Imagine a situation: a hacker walks into a nearby cafe and performs deauthentication to intercept hashes and subsequently guess user passwords on their basis.

And the script immediately detects such activity.

The signal strength makes it possible to estimate the distance between you and the hacker: – 30dBm means that the bastard is actually sitting in front of you.

PMKID capture

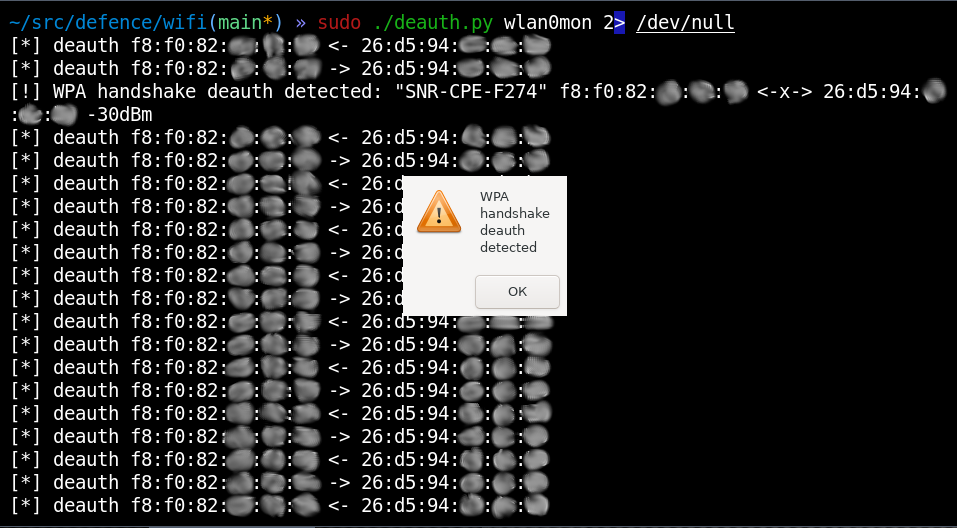

To cover a larger area, corporate wireless networks often use multiple access points with the same name. This ensures that moving employees are seamlessly switching from one access point to another. During authentication to such access points, the first EAPOL M1 message often contains a hash (PMKID) that is very similar to a handshake.

Importantly, the hash is sent by the access point, which makes it possible to capture it and guess the password without interaction with clients.

This attack is very popular among hackers and pentesters because it’s delivered quickly and silently and doesn’t incur adverse consequences. However, one of its features makes it possible to detect such attacks.

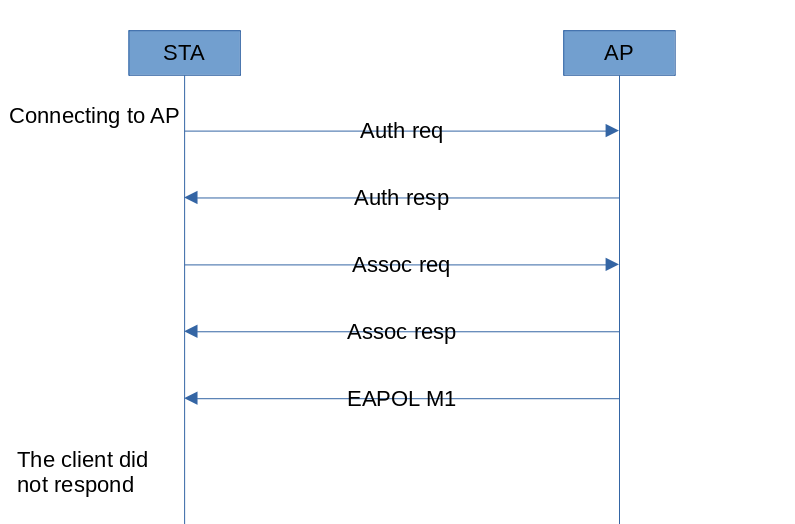

When a client attempts to authenticate to a WPA PSK access point, the client device always sends an EAPOL M2 packet after receiving M1.

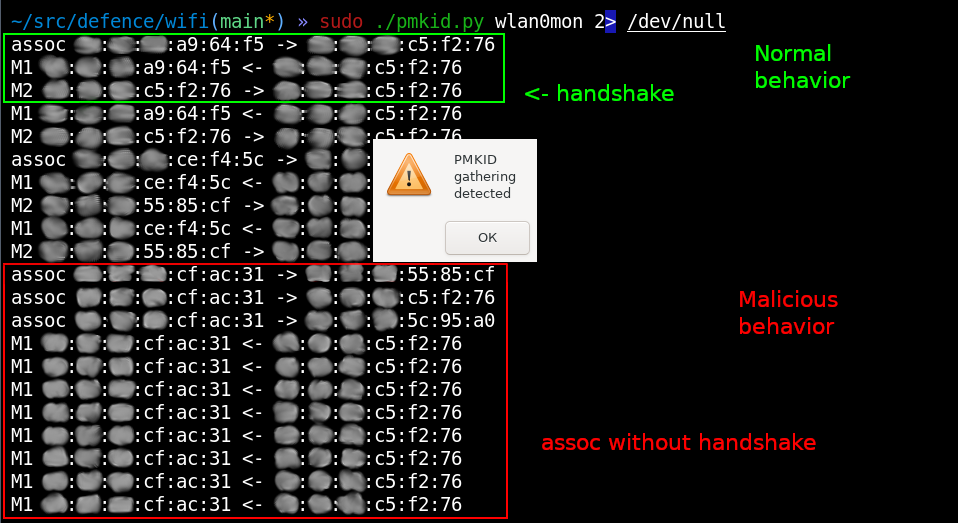

This is normal behavior. But for a hacker, an attempt to capture PMKID this way will result in unwanted capture of half-handshake (EAPOL M2). Some hacking utilities (e.g. Aircrack-ng) cannot show PMKID (EAPOL M1) when a handshake (EAPOL M2) is captured. Therefore, specialized hacking tools (e.g. hcxdumptool or bettercap) behave differently from a typical client: to capture PMKID, they don’t send M2 after connecting to a WPA PSK access point.

This enables you to catch the elusive hacker:

defence/wifi/pmkid.py#!/usr/bin/python3from scapy.all import *from threading import Threadfrom time import sleepfrom sys import argvfrom os import systemiface = argv[1]conf.verb = 0alerts = []def alert(client, essid): global aps, clients if client in alerts and essid in alerts: return print(f'[!] PMKID gathering detected: {client} {clients.get(client,{}).get("signal","-")}dBm to {essid}') system("zenity --warning --title='PMKID gathering detected' --text='PMKID gathering detected' &") #system("echo 'PMKID gathering detected' | festival --tts --language english") alerts.append(client) alerts.append(essid)aps = {}clients = {}def parse_raw_80211(p): signal = int(p[RadioTap].dBm_AntSignal or 0) if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "dBm_AntSignal") else 0 freq = p[RadioTap].ChannelFrequency if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "ChannelFrequency") else 0 if Dot11Beacon in p: # Beacon ap = p[Dot11].addr2 essid = str(p[Dot11Elt].info, "utf-8") if not ap in aps: aps[ap] = {"essid": essid, "m1":set(), "m2": set()} elif Dot11AssoReq in p: # Association req print("assoc %s -> %s" % (p[Dot11].addr2, p[Dot11].addr3)) clients[p[Dot11].addr2] = {"signal": signal} elif EAPOL in p and p[Dot11].addr3 in aps: #print("EAPOL") ap = p[Dot11].addr3 if p[Dot11].addr2 == ap: aps[ap]["m1"].add(p[Dot11].addr1) print('M1 %s <- %s' % (p[Dot11].addr1, ap)) elif p[Dot11].addr1 == ap: aps[ap]["m2"].add(p[Dot11].addr2) print('M2 %s -> %s' % (p[Dot11].addr1, ap)) #print(aps[ap])def analyze(): while True: for ap in aps.copy(): for client in aps[ap]["m1"] - aps[ap]["m2"]: alert(client, aps[ap]["essid"]) sleep(1)Thread(target=analyze, args=()).start()sniff(iface=iface, prn=parse_raw_80211, store=0)Imagine a situation: while you are monitoring the airwaves; a hacker passes by your office windows and automatically performs authentication to all wireless devices within sight.

And, of course, you can detect it.

You see strange behavior of a client who doesn’t send a handshake (M2), which indicates that the goal of this ‘client’ is to gather PMKID (i.e. receive M1).

Brute-forcing access points

If the two above-described attacks (handshake capture and PMKID capture) don’t bring any success to the attacker, then the bastard can go further.

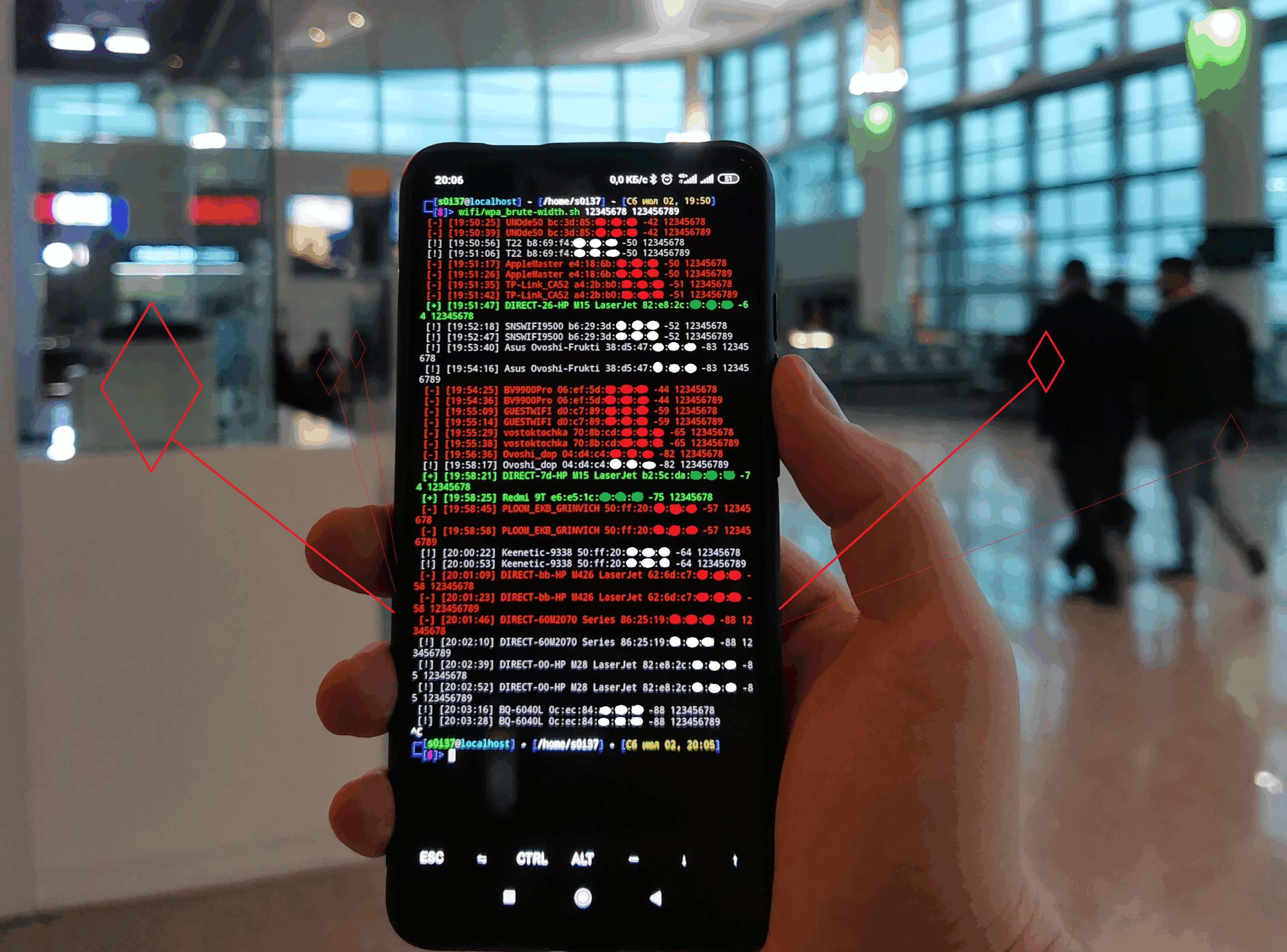

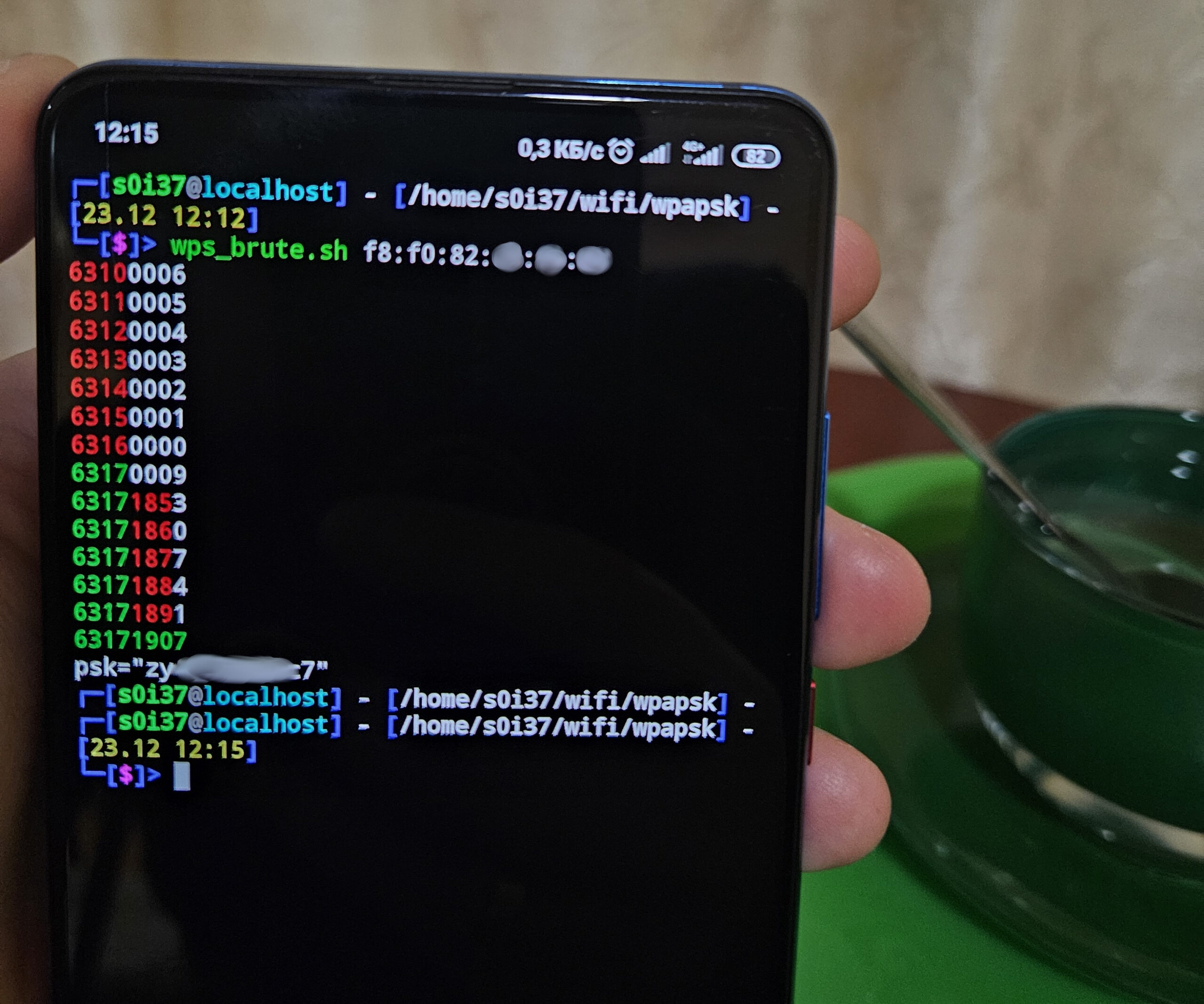

Generally speaking, the access point brute-forcing attack isn’t common among hackers, but in the article Brute-force on-the-fly. Attacking wireless networks in a simple and effective way I demonstrated that it can be successfully delivered. Furthermore, an attack involving brute-forcing of access point’s password is implemented very simply: after all, this is a legitimate function of any client device, which means that it can be delivered on the go from an Android phone without raising any suspicions.

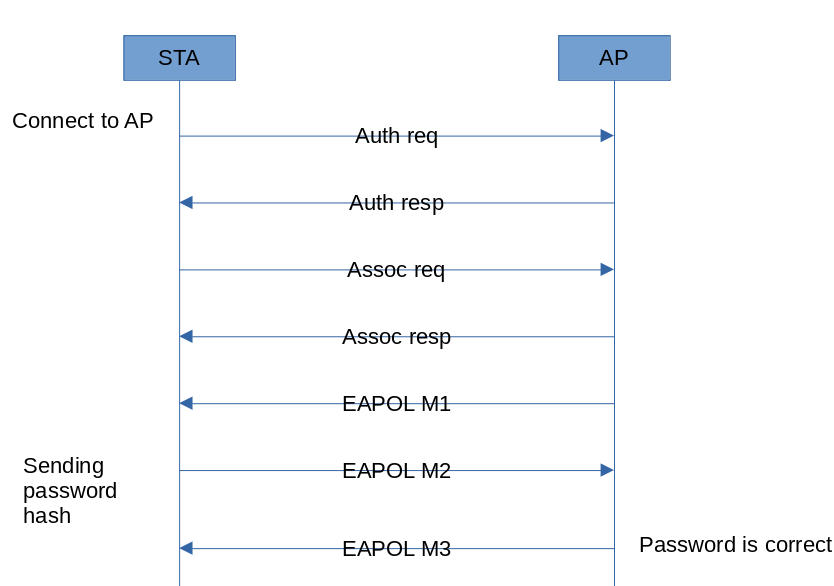

A successful attempt to authenticate to a WPA PSK wireless network differs from an unsuccessful one by an EAPOL M3 response from the access point.

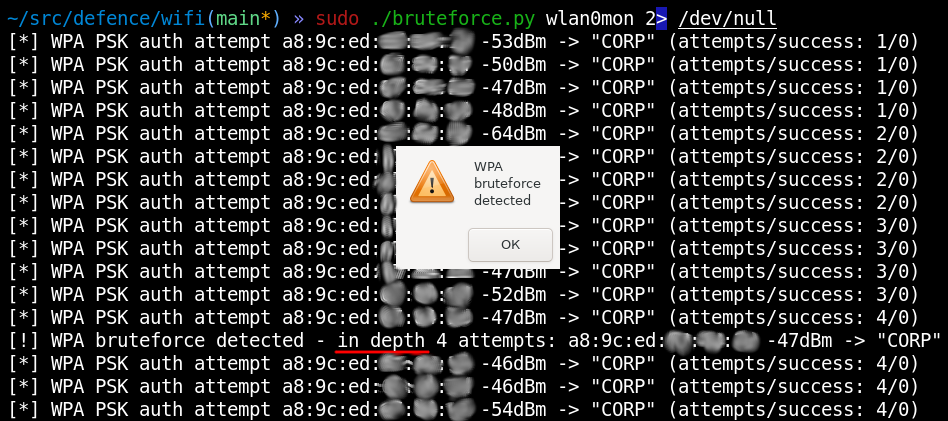

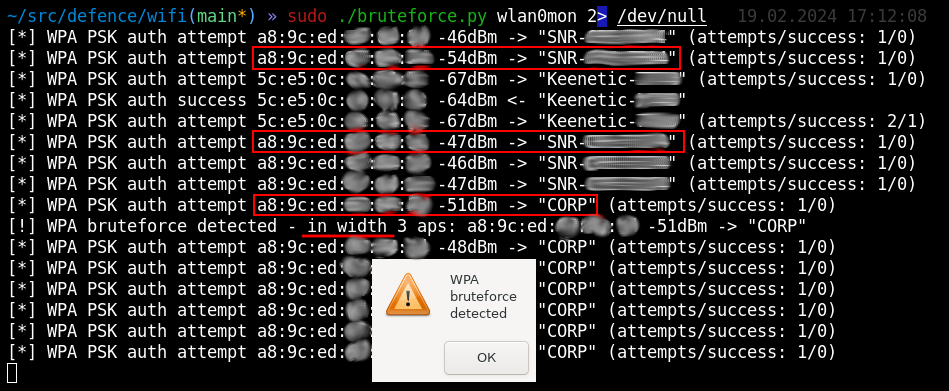

Therefore, all you have to do is listen to the airwaves and monitor authentication attempts (EAPOL M2) and successful authentications (EAPOL M3):

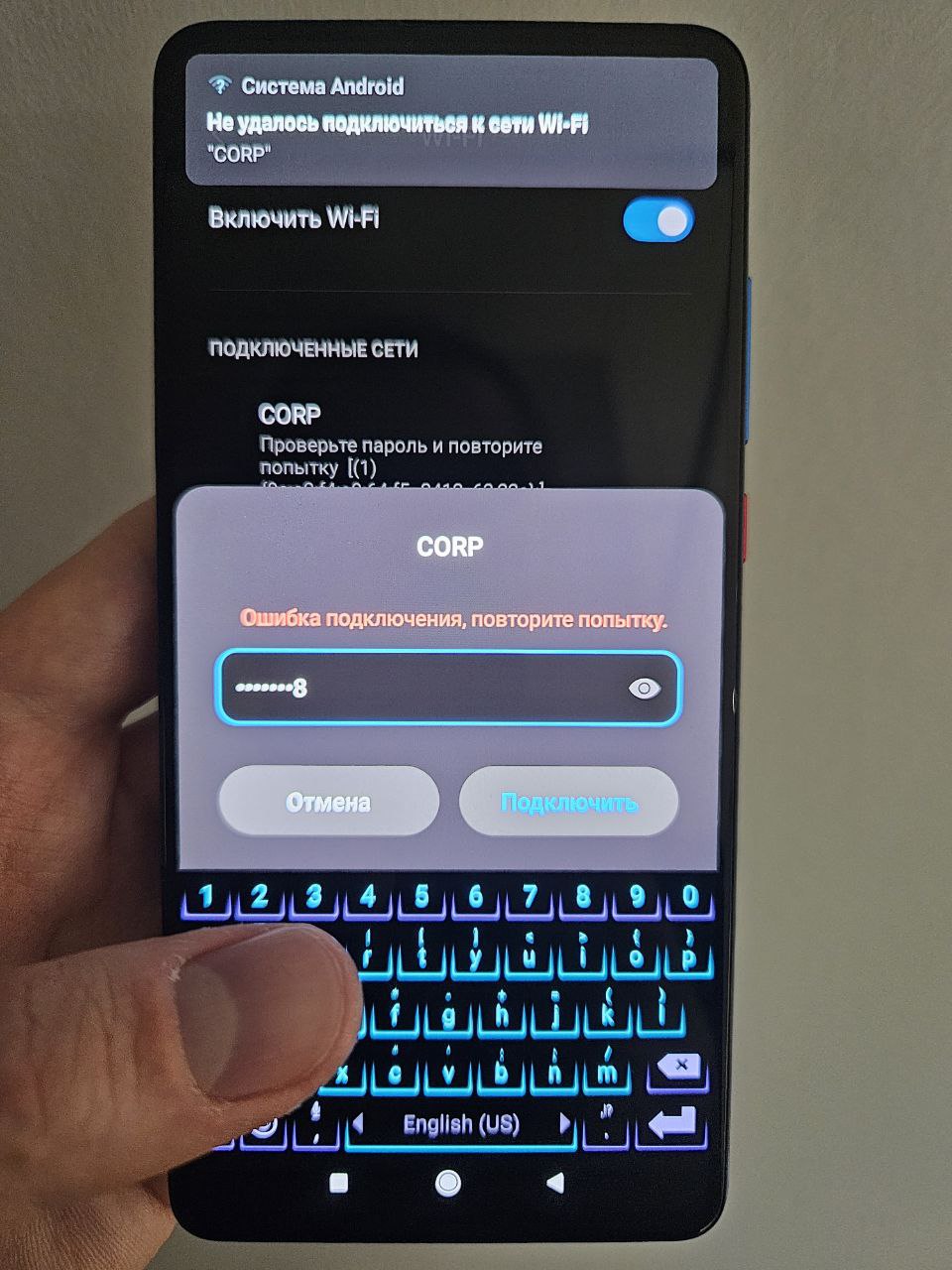

defence/wifi/brute.py#!/usr/bin/python3from scapy.all import *from threading import Threadfrom datetime import datetime, timedeltafrom time import sleepfrom sys import argvfrom os import systemiface = argv[1]conf.verb = 0MAX_PASSWORD_ATTEMPTS = 3MAX_APS_ATTEMPTS = 2alerts = []def alert(client, ap, reason): global aps, clients if client in alerts and ap in alerts: return print(f'[!] WPA bruteforce detected - {reason}: {client} {clients[client]["signal"]}dBm -> "{aps[ap]["essid"]}"') system("zenity --warning --title='WPA bruteforce detected' --text='WPA bruteforce detected' &") #system("echo 'WPA bruteforce detected' | festival --tts --language english") alerts.append(client) alerts.append(ap)aps = {}clients = {}def parse_raw_80211(p): signal = int(p[RadioTap].dBm_AntSignal or 0) if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "dBm_AntSignal") else 0 freq = p[RadioTap].ChannelFrequency if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "ChannelFrequency") else 0 if Dot11Beacon in p: # Beacon ap = p[Dot11].addr2 essid = str(p[Dot11Elt].info, "utf-8") if not ap in aps: aps[ap] = {"essid": essid} elif EAPOL in p and p[Dot11].addr3 in aps: ap = p[Dot11].addr3 if p[Dot11].addr2 == ap: client = p[Dot11].addr1 try: clients[client] except: clients[client] = {"signal": 0, "aps":{}} try: clients[client]["aps"][ap] except: clients[client]["aps"][ap] = {"m2":set(), "m3":0} if bytes(p[EAPOL].payload)[77:77+16] == b'\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00\x00': # AMIC, EAPOL M1 pass else: # EAPOL M3 clients[client]["aps"][ap]["m3"] += 1 print(f'[*] WPA PSK auth success {client} {signal}dBm <- "{aps[ap]["essid"]}"') clients[client]["signal"] = signal elif p[Dot11].addr1 == ap: # EAPOL M2 client = p[Dot11].addr2 try: clients[client] except: clients[client] = {"signal": 0, "aps":{}} try: clients[client]["aps"][ap] except: clients[client]["aps"][ap] = {"m2":set(), "m3":0} snonce = bytes(p[EAPOL].payload)[13:13+32] clients[client]["aps"][ap]["m2"].add(snonce) clients[client]["signal"] = signal print(f'[*] WPA PSK auth attempt {client} {signal}dBm -> "{aps[ap]["essid"]}" (attempts/success: {len(clients[client]["aps"][ap]["m2"])}/{clients[client]["aps"][ap]["m3"]})')def analyze(): while True: for client in clients: for ap in clients[client]["aps"]: if len(clients[client]["aps"][ap]["m2"]) > MAX_PASSWORD_ATTEMPTS and clients[client]["aps"][ap]["m3"] == 0: alert(client, ap, f'in depth {len(clients[client]["aps"][ap]["m2"])} attempts') # in depth if len(clients[client]["aps"]) > MAX_APS_ATTEMPTS: alert(client, ap, f'in width {len(clients[client]["aps"])} aps') # in width sleep(1)Thread(target=analyze, args=()).start()sniff(iface=iface, prn=parse_raw_80211, store=0)The hacker doesn’t have to run any special software; instead, they can simply try several passwords while attempting to connect to your access point from a regular phone.

Surveillance cameras are unable to detect such an attack, but you can see it.

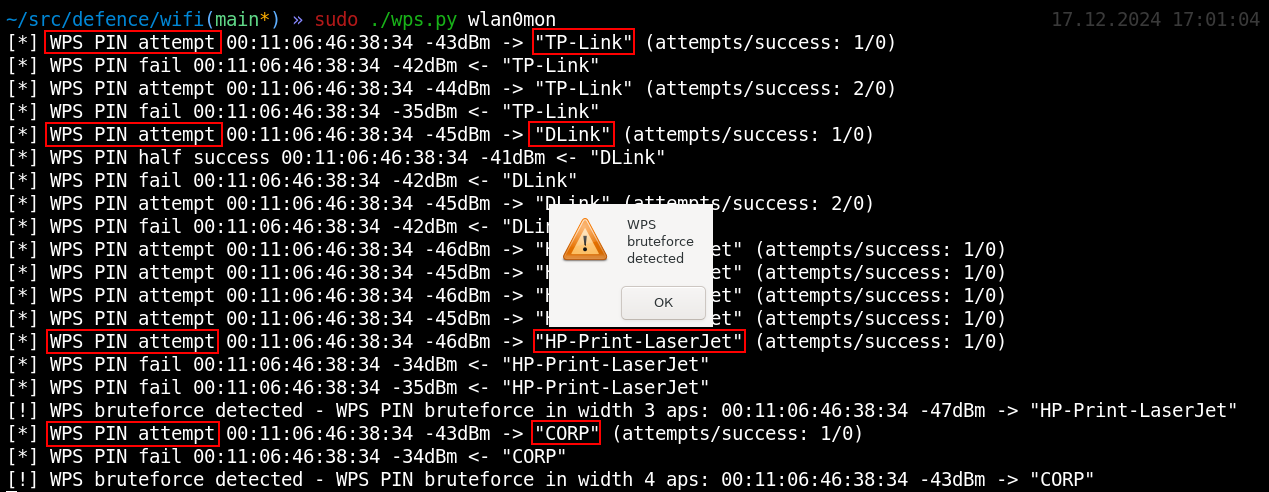

You see that the attacker made four attempts to guess the password for your access point. However, the hacker may not necessarily attack an official access point in a ‘blunt’ way. Instead, the bastard can try password spraying: attacking all audible access points while walking along the perimeter of your company in the hope of finding an alternative entry point (e.g. through a corporate wireless printer). For this attack, just one or two weakest passwords could suffice.

Such attacks are almost undetectable since only one or two authentication attempts are made on each device. But analysis of the overall picture easily reveals the attack: in addition to brute-forcing in depth, the script also monitors brute-forcing in width attempts.

A bona fide client won’t try passwords to several access points at once, which means that this is a hacker testing the strength of your wireless network.

WPS

Although the Wi-Fi Protected Setup (WPS) technology is considered outdated, it’s still widely employed in ‘unofficial’ access points used in secondary (e.g. service or test) wireless networks at the company’s physical perimeter. After all, this is the primary task of any intruder: find something obsolete and neglected by security personnel (i.e. something vulnerable).

WPS is a technology used for simplified connection to WPA networks. It’s implemented by entering an 8-digit code. If the code is correct, the access point sends to the client a regular WPA PSK key enabling the client to connect. However, the golden rule of information security is: comfortable and handy solutions are rarely secure. In addition, WPS is marred by vulnerabilities.

Attacks targeting WPS are quite diverse. Furthermore, three such attacks out of four can be delivered in just a few seconds, thus, making it possible to attack vulnerable access points on the go.

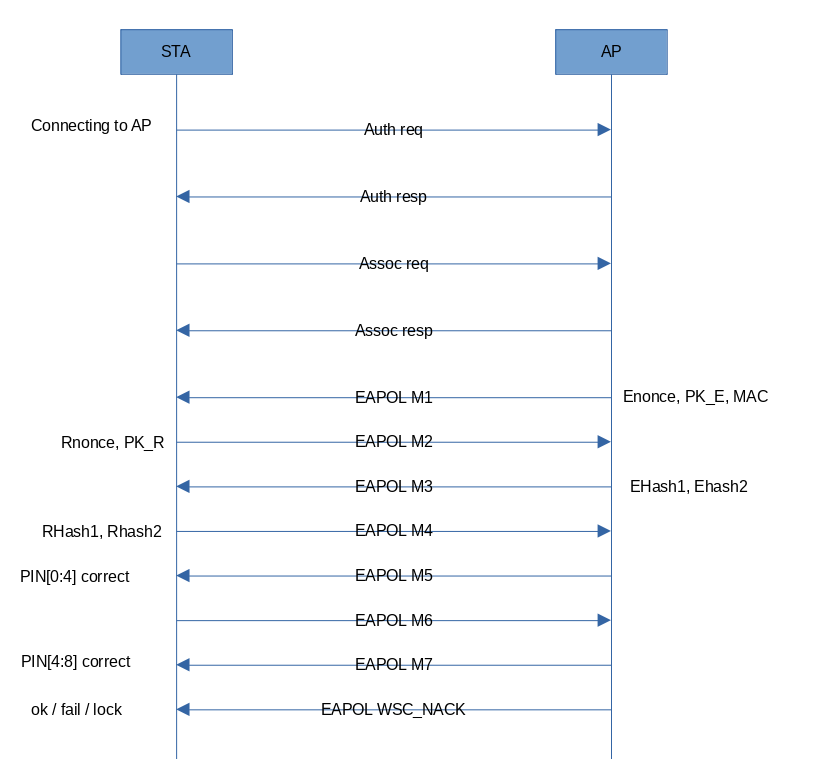

The WPS technology is sophisticated enough and involves eight handshakes: eight EAPOL packets (four on each side).

Unlike WPA PSK, secret keys are securely transferred using the Diffie–Hellman (DH) algorithm. As a result, you cannot guess attacker’s real intentions. But the EAPOL protocol discloses plenty of information about the status of a PIN-based connection. As a result, you can find out (to a certain extent!) what’s going on. The script below makes it possible to understand the situation with WPS on the airwaves:

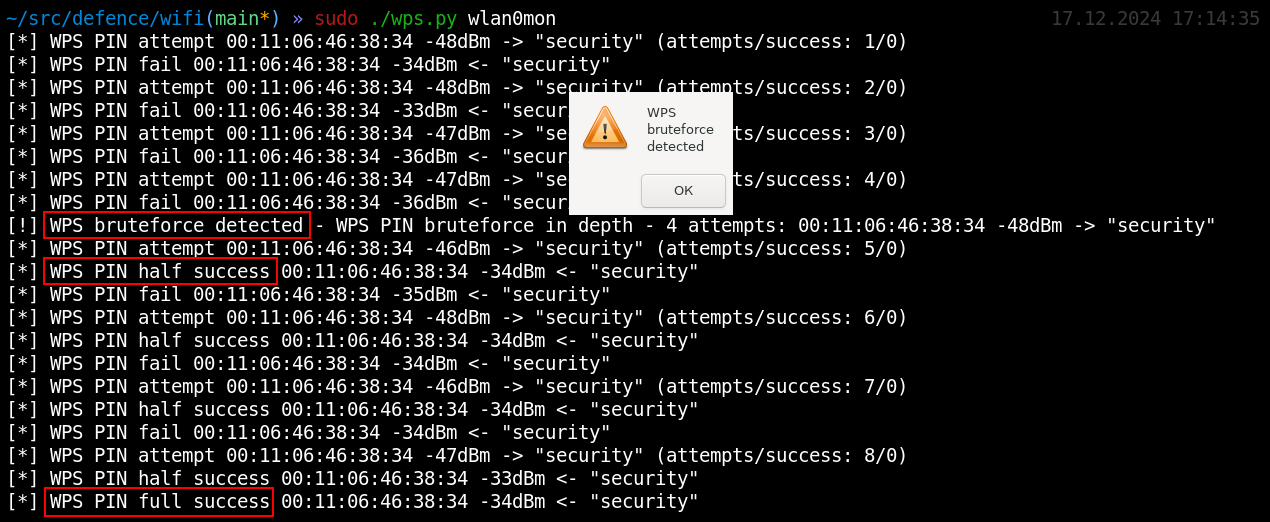

defence/wifi/wps.py#!/usr/bin/python3from scapy.all import *from threading import Threadfrom datetime import datetimefrom time import sleepfrom sys import stdout, argvfrom os import systemiface = argv[1]conf.verb = 0MAX_PIN_ATTEMPTS = 3MAX_APS_ATTEMPTS = 2debug = 0alerts = []def alert(client, ap, reason): global aps, clients if client in alerts and ap in alerts: return print(f'[!] WPS bruteforce detected - {reason}: {client} {clients[client]["signal"]}dBm -> "{aps[ap]["essid"]}"') system("zenity --warning --title='WPS bruteforce detected' --text='WPS bruteforce detected' &") #system("echo 'WPS bruteforce detected' | festival --tts --language english") alerts.append(client) alerts.append(ap)aps = {}clients = {}e_nonce = None; r_nonce = None; dh_peer_public_key = None; dh_own_public_key = None; enrollee_mac = None; r_hash1 = None; r_hash2 = Nonedef parse_raw_80211(p): global e_nonce, r_nonce, dh_peer_public_key, dh_own_public_key, enrollee_mac, r_hash1, r_hash2 signal = int(p[RadioTap].dBm_AntSignal or 0) if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "dBm_AntSignal") else 0 freq = p[RadioTap].ChannelFrequency if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "ChannelFrequency") else 0 ap = None; client = None; d = None if Dot11Beacon in p: # Beacon ap = p[Dot11].addr2 essid = str(p[Dot11Elt].info, "utf-8") if not ap in aps: aps[ap] = {"essid": essid} elif EAP in p and p[EAP].type == 254: # WPS ap = p[Dot11].addr3 e_hash1 = None r_hash1 = None success1 = False success2 = False ok = False fail = False lock = False offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x22\x00\x01") message_type = p[EAP].load[offset+4] message_types = {0x04: "M1", 0x05: "M2", 0x07: "M3", 0x08: "M4", 0x09: "M5", 0x0a: "M6", 0x0b: "M7", 0x0c: "M8", 0x0e: "WSC_NACK"} if message_type in message_types.keys(): if message_type in [0x04, 0x07, 0x09, 0x0b]: client = p[Dot11].addr1 d = "->" elif message_type in [0x05, 0x08, 0x0a, 0x0c]: client = p[Dot11].addr2 d = "<-" elif message_type == 0x0e: if p[EAP].code == 1: client = p[Dot11].addr1 d = "->" elif p[EAP].code == 2: client = p[Dot11].addr2 d = "<-" if d: if debug >= 1: print(f"WPS {message_types.get(message_type)} {ap} {d} {client}") if message_types[message_type] == "M1": offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x1a") + 4 e_nonce = p[EAP].load[offset:offset+16] if debug >= 2: print(f" e_nonce: {e_nonce.hex()}") offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x20\x00\x06") + 4 enrollee_mac = p[EAP].load[offset:offset+6] if debug >= 2: print(f" enrollee_mac: {enrollee_mac.hex()}") offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x32\x00\xc0") + 4 dh_peer_public_key = p[EAP].load[offset:offset+192] # PK_E if debug >= 2: print(f" dh_peer_public_key: {dh_peer_public_key.hex()}") if message_types[message_type] == "M2": offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x32\x00\xc0") + 4 dh_own_public_key = p[EAP].load[offset:offset+192] # PK_R if debug >= 2: print(f" dh_own_public_key: {dh_own_public_key.hex()}") offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x39\x00\x10") + 4 r_nonce = p[EAP].load[offset:offset+16] if debug >= 2: print(f" r_nonce: {r_nonce.hex()}") if message_types[message_type] == "M3": offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x14\x00\x20") + 4 e_hash1 = p[EAP].payload.load[offset:offset+32] if debug >= 2: print(f" e_hash1: {e_hash1.hex()}") offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x15\x00\x20") + 4 e_hash2 = p[EAP].payload.load[offset:offset+32] if debug >= 2: print(f" e_hash2: {e_hash2.hex()}") if message_types[message_type] == "M4": offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x3d\x00\x20") + 4 r_hash1 = p[EAP].payload.load[offset:offset+32] if debug >= 2: print(f" r_hash1: {r_hash1.hex()}") offset = p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x3e\x00\x20") + 4 r_hash2 = p[EAP].payload.load[offset:offset+32] if debug >= 2: print(f" r_hash2: {r_hash2.hex()}") if message_types[message_type] == "M5": success1 = True if message_types[message_type] == "M7": success2 = True if message_types[message_type] == "WSC_NACK": if d == "->": if p[EAP].load.find(b"\x10\x05\x00\x08") != -1: ok = True elif p[EAP].load.find(b"\x00\x02\x00\x12") != -1: fail = True elif p[EAP].load.find(b"\x00\x02\x00\x0f") != -1: lock = True if ap and client: try: aps[ap] except: aps[ap] = {"essid": ""} try: clients[client] except: clients[client] = {"signal": 0, "aps":{}} try: clients[client]["aps"][ap] except: clients[client]["aps"][ap] = {"e_hashes":set(), "r_hashes": set(), "fails": 0, "success_half": 0, "success_full": 0} clients[client]["signal"] = signal if e_hash1: clients[client]["aps"][ap]["e_hashes"].add(e_hash1) if r_hash1: clients[client]["aps"][ap]["r_hashes"].add(r_hash1) print(f'[*] WPS PIN attempt {client} {signal}dBm -> "{aps[ap]["essid"]}" (attempts/success: {len(clients[client]["aps"][ap]["r_hashes"])}/{clients[client]["aps"][ap]["success_full"]})') if success1: clients[client]["aps"][ap]["success_half"] += 1 print(f'[*] WPS PIN half success {client} {signal}dBm <- "{aps[ap]["essid"]}"') if success2: clients[client]["aps"][ap]["success_full"] += 1 print(f'[*] WPS PIN full success {client} {signal}dBm <- "{aps[ap]["essid"]}"') if fail: clients[client]["aps"][ap]["fails"] += 1 print(f'[*] WPS PIN fail {client} {signal}dBm <- "{aps[ap]["essid"]}"') if lock: print(f'[*] WPS PIN lock {client} {signal}dBm <- "{aps[ap]["essid"]}"')def analyze(): while True: for client in clients: for ap in clients[client]["aps"]: if len(clients[client]["aps"][ap]["r_hashes"]) > MAX_PIN_ATTEMPTS and clients[client]["aps"][ap]["success_full"] == 0: alert(client, ap, f'WPS PIN bruteforce in depth - {len(clients[client]["aps"][ap]["r_hashes"])} attempts') elif clients[client]["aps"][ap]["success_half"] > 1: alert(client, ap, f'WPS PIN bruteforce in depth - half pin {clients[client]["aps"][ap]["success_half"]} matches') if len(clients[client]["aps"]) > MAX_APS_ATTEMPTS: alert(client, ap, f'WPS PIN bruteforce in width {len(clients[client]["aps"])} aps') sleep(1)Thread(target=analyze, args=()).start()sniff(iface=iface, prn=parse_raw_80211, store=0)Imagine a situation: a hacker sitting in a cafe across from your office notices that one of the target access points has WPS version 1 enabled, which means that it’s not blocked, and the entire PIN code space can be enumerated. Such an attack takes several hours, but the hacker isn’t in a hurry.

And you can see hacker’s true intentions: the bastard is brute-forcing an access point.

It can be seen in the above screenshot that the wps. script clearly detects two milestones on the airwaves: (1) hacker successfully guesses the first half of the PIN code; and (2) hacker successfully guesses its second half (which means that your wireless network has been completely compromised).

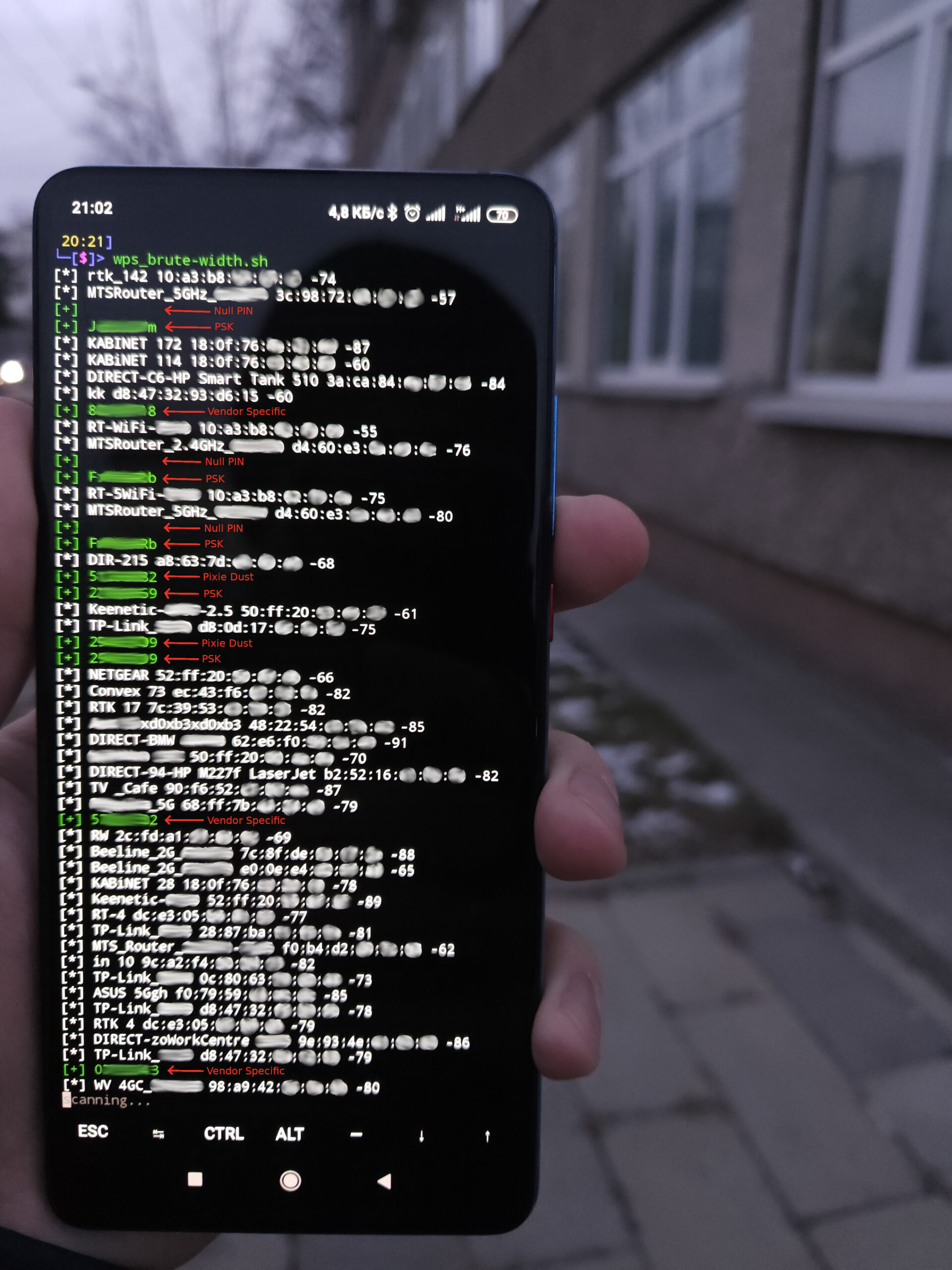

In the meantime, another hacker in the hope to find a ‘low-hanging fruit’ walks along the building and delivers fast WPS attacks (Pixie Dust, Vendor Specific PIN, and Null PIN) against all access points within the range.

But the above script can detect such abnormal WPS activity involving simultaneous authentications to multiple access points.

If a device with the same MAC address performs one or two checks on all access points within its range, this clearly indicates an intrusion attempt. Generally speaking, the very fact that somebody is using the unpopular and obsolete WPS should raise your suspicions.

Now let’s proceed to RoqueAP attacks that target clients (i.e. users and user devices) and are delivered from the access point side.

Evil Twin

Hackers like this attack because it targets the weakest link of any perimeter: a human being. Accordingly, such attacks will always be relevant. Novice hackers can try them from the very beginning; while experienced ones, only if all above-described attempts to hack a wireless network fail.

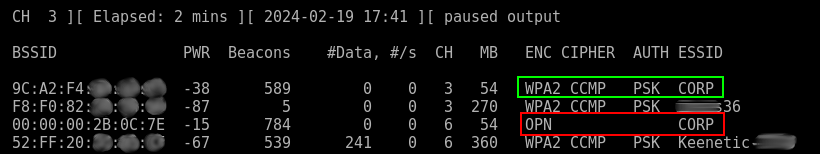

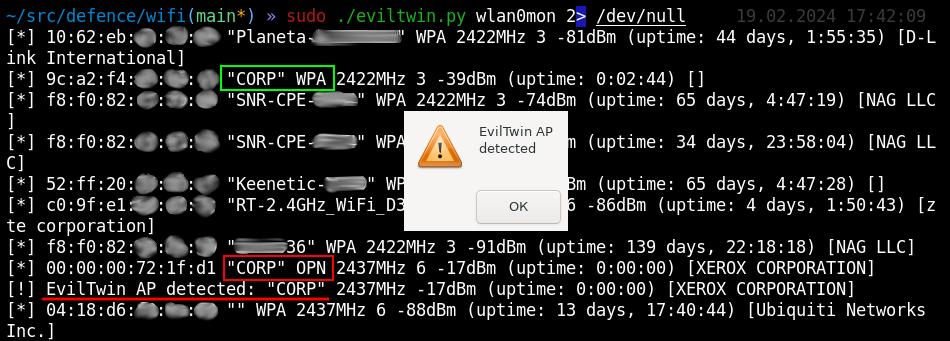

It’s pretty easy to detect an ‘evil twin’ access point. You just monitor all WPA PSK networks, and if an open network with the same name suddenly appears nearby, this indicates, with a high degree of probability, an Evil Twin attack.

Two networks with the same name featuring different authentication types cannot exist together because client devices remember connection data based on the network name.

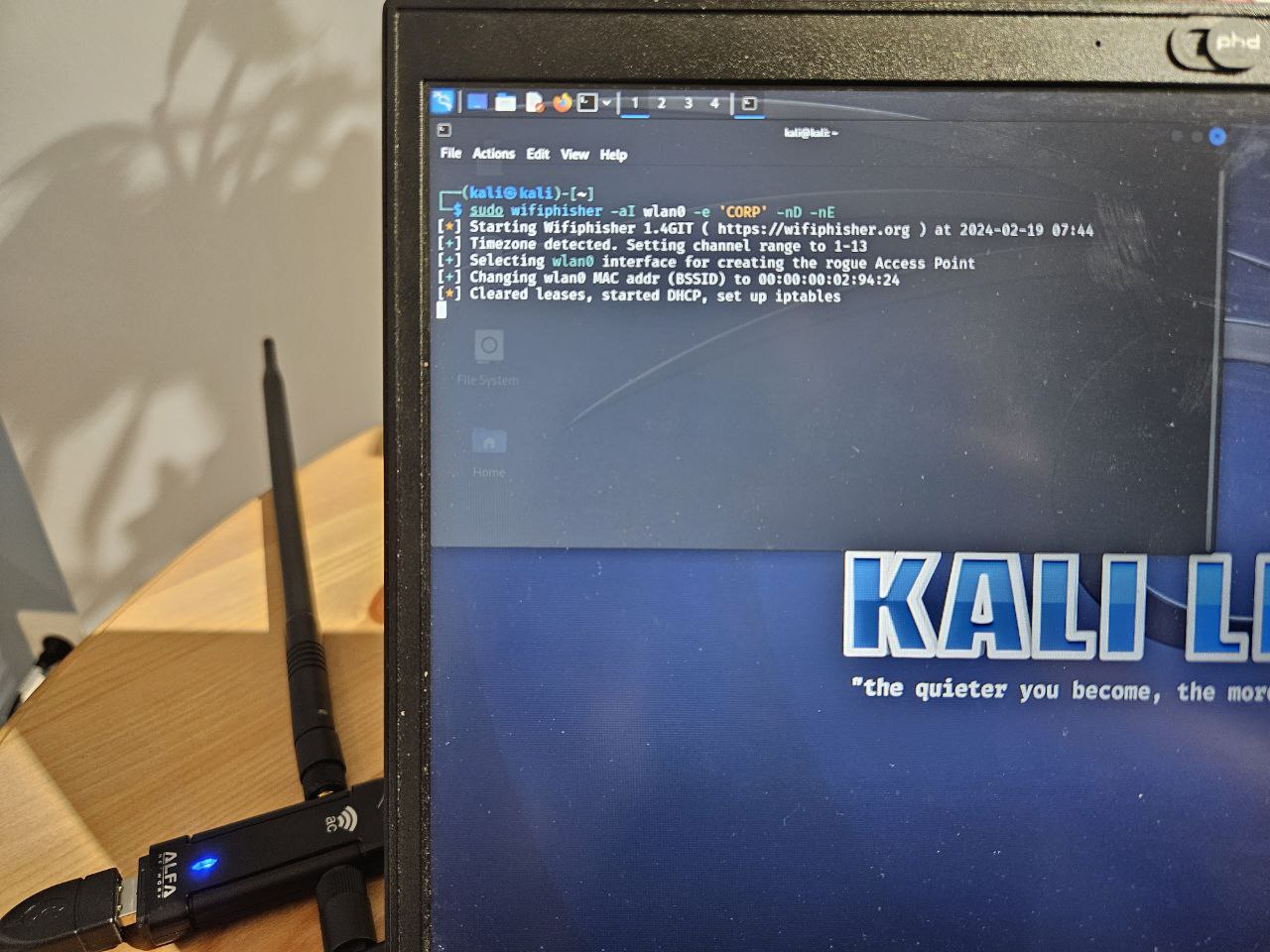

defence/wifi/eviltwin.py#!/usr/bin/python3from scapy.all import *from threading import Threadfrom mac_vendor_lookup import MacLookup # pip3 install mac-vendor-lookupfrom datetime import datetime, timedeltafrom time import sleepfrom sys import argvfrom os import systemiface = argv[1]conf.verb = 0oui = MacLookup()alerts = []def alert(ap): global aps if ap in alerts: return try: vendor = oui.lookup(ap) except: vendor = "" print(f'[!] EvilTwin AP detected: "{aps[ap]["essid"]}" {aps[ap]["freq"]}MHz {aps[ap]["signal"]}dBm (uptime: {aps[ap]["uptime"]}) [{vendor}]') system("zenity --warning --title='EvilTwin AP detected' --text='EvilTwin AP detected' &") #system("echo 'EvilTwin AP detected' | festival --tts --language english") alerts.append(ap)def get_uptime(timestamp): delta = timedelta(microseconds=timestamp) upTime = str(delta).split('.')[0] #upSince = str(datetime.now() - delta).split('.')[0] return upTimeaps = {}ENC_CAP = int(Dot11Beacon(cap='privacy').cap)ENC_FIELD = int(Dot11(FCfield='protected').FCfield)def parse_raw_80211(p): signal = int(p[RadioTap].dBm_AntSignal or 0) if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "dBm_AntSignal") else 0 freq = p[RadioTap].ChannelFrequency if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "ChannelFrequency") else 0 if Dot11Beacon in p: # Beacon ap = p[Dot11].addr2 essid = str(p[Dot11Elt].info, "utf-8") enc = "WPA" if ENC_CAP & int(p[Dot11Beacon].cap) else "OPN" if Dot11EltDSSSet in p: channel = p[Dot11EltDSSSet].channel if not ap in aps: aps[ap] = {"essid": essid, "enc": enc, "freq": freq, "channel": channel, "uptime": get_uptime(p[Dot11Beacon].timestamp), "signal": signal} try: vendor = oui.lookup(ap) except: vendor = "" print(f'[*] {ap} "{essid}" {enc} {freq}MHz {channel} {signal}dBm (uptime: {aps[ap]["uptime"]}) [{vendor}]') if aps[ap]["freq"] != freq and aps[ap]["signal"] < signal: aps[ap]["signal"] = signal aps[ap]["freq"] = freq aps[ap]["channel"] = channeldef analyze(): while True: wpa = set([]) for ap in aps.copy(): if aps[ap]["enc"] == "WPA": wpa.add(aps[ap]["essid"]) for ap in aps.copy(): if aps[ap]["enc"] == "OPN": if aps[ap]["essid"] in wpa: alert(ap) sleep(1)Thread(target=analyze, args=()).start()sniff(iface=iface, prn=parse_raw_80211, store=0)This script monitors all access points, both open and WPA, calculates their uptime, and determines their vendors based on the OUI database. Imagine a situation: a nearby hacker deploys an ‘evil twin’ wireless network.

And you immediately detect it.

Note a fairly low uptime: in corporate access points, it’s normally measured in days and months; while a rogue access point could be deployed a couple of minutes ago. In addition, hackers can combine this attack with logical jamming of legitimate access points (by sending deauthentication packets to disconnect clients). And you already know how to detect this attack.

WPA Enterprise — GTC downgrade

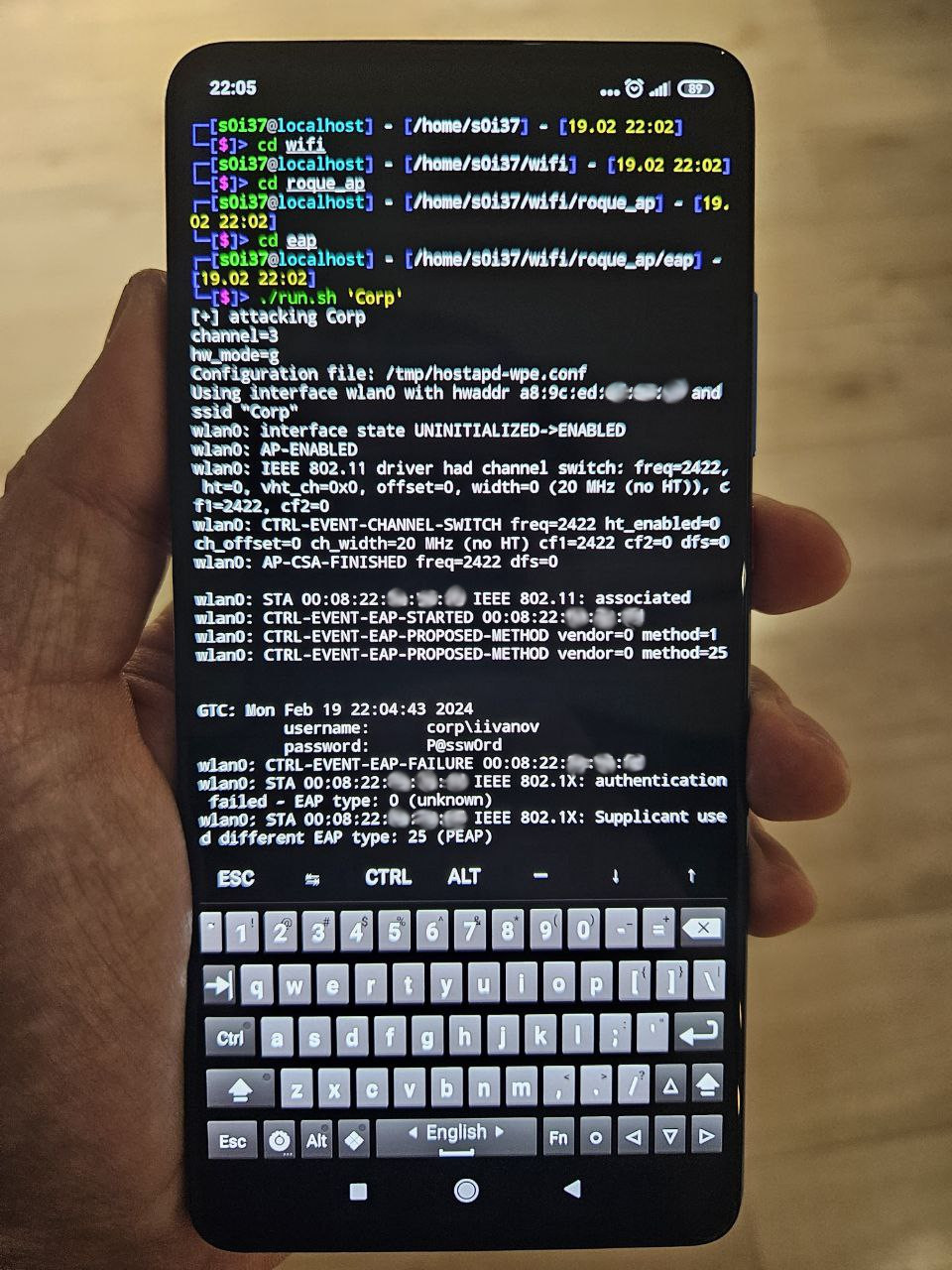

If your company uses a WPA Enterprise wireless network (where each client authenticates with their own login and password), then a hacker will definitely try such an attack.

WPA Enterprise wireless networks use a designated authentication server and can receive client’s credential in multiple ways. Some of these ways are very insecure: the client can be forced to submit the password in plain text or as a hash. Even if you use highly secure WPA Enterprise TLS, there is no guarantee that all user devices are configured correctly and aren’t susceptible to authentication downgrade attacks. After all, the targets of this attack are clients.

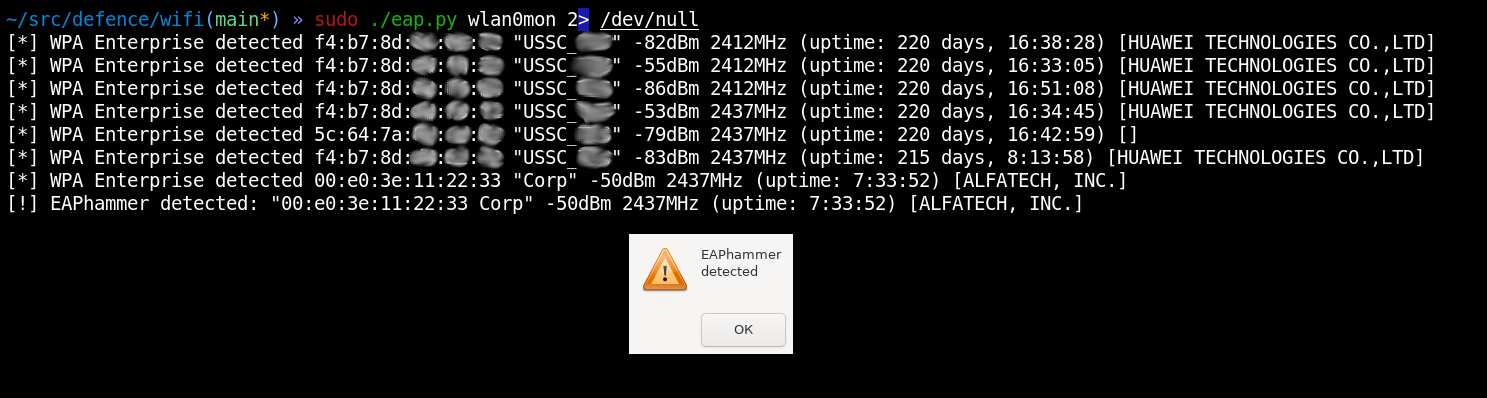

‘Normal’ WPA Enterprise access points will request clients to transmit their credentials in the most secure way, but specialized rogue access points use the reverse order of authentication methods (i.e. from insecure to secure ones) to downgrade authentication. This feature makes it possible to detect such attacks:

defence/wifi/eap.py#!/usr/bin/python3from scapy.all import *from threading import Threadfrom mac_vendor_lookup import MacLookup # pip3 install mac-vendor-lookupfrom datetime import datetime, timedeltafrom time import sleepfrom random import randomfrom sys import argvfrom os import systemiface = argv[1]conf.iface = ifaceconf.verb = 0oui = MacLookup()alerts = []def alert(ap): global aps if ap in alerts: return try: vendor = oui.lookup(ap) except: vendor = "" print(f'[!] EAPhammer detected: "{ap} {aps[ap]["essid"]}" {aps[ap]["signal"]}dBm {aps[ap]["freq"]}MHz (uptime: {aps[ap]["uptime"]}) [{vendor}]') system("zenity --warning --title='EAPhammer detected' --text='EAPhammer detected' &") #system("echo 'EAPhammer detected' | festival --tts --language english") alerts.append(ap)def get_uptime(timestamp): delta = timedelta(microseconds=timestamp) upTime = str(delta).split('.')[0] #upSince = str(datetime.now() - delta).split('.')[0] return upTimeaps = {}beacons = set()def parse_raw_80211(p): global beacons signal = int(p[RadioTap].dBm_AntSignal or 0) if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "dBm_AntSignal") else 0 freq = p[RadioTap].ChannelFrequency if hasattr(p[RadioTap], "ChannelFrequency") else 0 if Dot11Beacon in p: # Beacon ap = p[Dot11].addr2 essid = str(p[Dot11Elt].info, "utf-8") beacons.add(ap) if not ap in aps: if "privacy" in p[Dot11Beacon].cap: layer = p[Dot11Elt].payload while True: if not layer: break if layer.ID == 0x30: if layer.info[17] == 1: enc = "EAP" else: enc = "WPA" break layer = layer.payload else: enc = "OPN" aps[ap] = {"essid": essid, "enc": enc, "signal": signal, "freq": freq, "uptime": get_uptime(p[Dot11Beacon].timestamp)} if enc == "EAP": try: vendor = oui.lookup(ap) except: vendor = "" print(f'[*] WPA Enterprise detected {ap} "{essid}" {signal}dBm {freq}MHz (uptime: {aps[ap]["uptime"]}) [{vendor}]') elif 0 and Dot11ProbeResp in p: # hidden, karma if p[Dot11].subtype == 5: ap = p[Dot11].addr2 essid = str(p[Dot11Elt].info, "utf-8") aps[ap] = {"essid": essid, "enc": "EAP", "signal": signal, "freq": freq, "uptime": 0}is_assoc = Falseis_ident = Falsepeap_type = Nonedef connect(ap, essid): global is_assoc, is_ident, peap_type is_assoc = False is_ident = False peap_type = None def get_random_mac(l=6): return ':'.join(list(map(lambda x:"%02x"%int(random()*0xff),range(l)))) source = "00:" + get_random_mac(5) #print(f" > auth req {ap}") authorization_request = RadioTap()/Dot11(proto=0, FCfield=0, subtype=11, addr2=source, addr3=ap, addr1=ap, SC=0, type=0)\

/ Dot11Auth(status=0, seqnum=1, algo=0) if not srp1(authorization_request, verbose=0, timeout=1.0): return #print(f" > auth resp {ap}") def get_assoc_resp(): def handle(p): global is_assoc, is_ident seen_receiver = p[Dot11].addr1 seen_sender = p[Dot11].addr2 seen_bssid = p[Dot11].addr3 if ap.lower() == seen_bssid.lower() and \

ap.lower() == seen_sender.lower() and \

source.lower() == seen_receiver.lower(): if Dot11AssoResp in p: #print(f" < assoc resp {ap}") is_assoc = True elif EAP in p and p[EAP].code == 1: #print(f" < ident req {ap}") is_ident = True sniff(iface=iface, lfilter=lambda p: p.haslayer(Dot11AssoResp) or p.haslayer(EAP), stop_filter=handle, timeout=1.0, store=0) #print(f" > assoc req {ap}") association_request = RadioTap()/Dot11(proto=0, FCfield=0, subtype=0, addr2=source, addr3=ap, addr1=ap, SC=0, type=0)\

/ Dot11AssoReq(listen_interval=1, cap=0x3114)\

/ Dot11Elt(ID=0, len=len(essid), info=essid)\

/ Dot11Elt(ID=1, len=8, info=b'\x82\x84\x8b\x96\x0c\x12\x18\x24')\

/ Dot11Elt(ID=48, len=0x14, info=b'\x01\x00\x00\x0f\xac\x04\x01\x00\x00\x0f\xac\x04\x01\x00\x00\x0f\xac\x01\x00\x00')\

/ Dot11Elt(ID=50, len=4, info=b'\x30\x48\x60\x6c')\

/ Dot11Elt(ID=59, len=0x14, info=b'\x51\x51\x53\x54\x73\x74\x75\x76\x77\x78\x79\x7a\x7b\x7c\x7d\x7e\x7f\x80\x81\x82')\

/ Dot11Elt(ID=221, len=8, info=b'\x8c\xfd\xf0\x01\x01\x02\x01\x00') Thread(target=get_assoc_resp).start() sendp(association_request, verbose=0) wait = 1.0 while not is_ident and wait > 0: sleep(0.001) wait -= 0.001 if not is_ident: return peap_type = 0 def get_ident(): def handle(p): global peap_type seen_receiver = p[Dot11].addr1 seen_sender = p[Dot11].addr2 seen_bssid = p[Dot11].addr3 if ap.lower() == seen_bssid.lower() and \

ap.lower() == seen_sender.lower() and \

source.lower() == seen_receiver.lower(): if EAP_PEAP in p: #print(f" > peap req {ap}") peap_type = p[EAP_PEAP].type sniff(iface=iface, lfilter=lambda p: p.haslayer(EAP_PEAP), stop_filter=handle, timeout=5, store=0) #print(f" > ident resp {ap}") eap_identity_response = RadioTap()/Dot11(proto=0, FCfield=1, subtype=8, addr2=source, addr3=ap, addr1=ap, SC=0, type=2, ID=55808)\

/ Dot11QoS(TID=6, TXOP=0, EOSP=0) \

/ LLC(dsap=0xaa, ssap=0xaa, ctrl=0x3)\

/ SNAP(OUI=0, code=0x888e)\

/ EAPOL(version=1, type=0, len=9)\

/ EAP(code=2, id=103, type=1, identity=b'user') Thread(target=get_ident).start() sendp(eap_identity_response, verbose=0, count=100) wait = 1.0 while not peap_type and wait > 0: sleep(0.001) wait -= 0.001 #print(f" > done {ap}") return peap_typechecked = []def analyze(): global checked, beacons while True: for ap in aps.copy(): if not ap in checked and aps[ap]["enc"] == "EAP" and ap in beacons: peap_type = connect(ap, aps[ap]["essid"]) if peap_type != None: checked.append(ap) if peap_type == 25: # CTRL-EVENT-EAP-PROPOSED-METHOD vendor=0 method=25 alert(ap) beacons = set() sleep(1)Thread(target=analyze, args=()).start()sniff(iface=iface, prn=parse_raw_80211, store=0)This script monitors only WPA Enterprise wireless networks by connecting to each of them and analyzing the authentication methods offered by their access points.

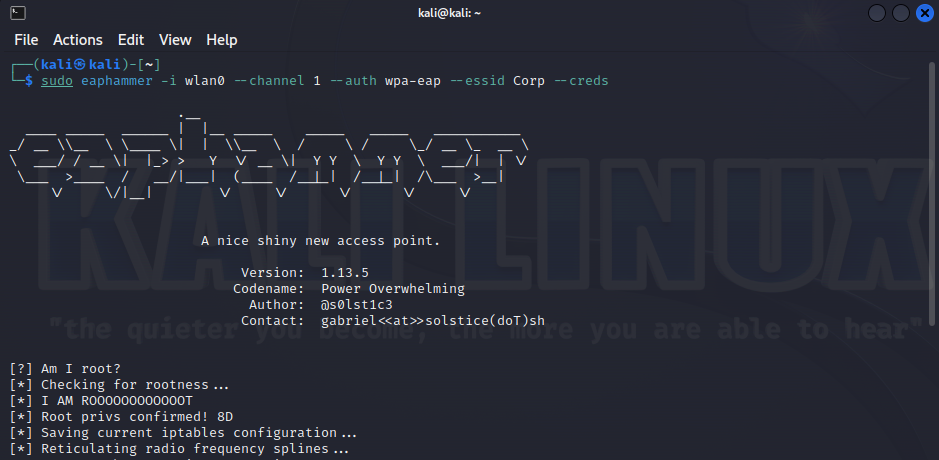

Imagine a situation: a hacker is hanging around not far from the reception and waiting for employees to arrive.

At first glance, this is an ordinary person with a phone in their hand. In the meanwhile, you are monitoring the airwaves for the presence of WPA Enterprise networks. And if another network with the same name is suddenly detected, then this is the first alarm bell. If an access point cannot be seen when you begin monitoring, but appears after some time, this indicates that it’s probably mobile (i.e. a phone or laptop), which isn’t typical for a legitimate WPA Enterprise access point, but very typical for a hacker.

You can also see that the MAC address of this device indicates a different vendor unrelated to legitimate access points (in this particular case, it’s an AlfaTech wireless network card very popular among hackers). In addition, you see a low (several hours) uptime, which is incommensurably less compared to legitimate access points (several months).

By the way, the signal level indicates that the hacker isn’t that far from you.

KARMA

Detection of the KARMA technique puts an end to all hacker’s endeavors. Interestingly, this attack is easier to detect compared to all above-described ones.

The KARMA attack isn’t as widespread as other wireless attacks. More information about it can be found in the article KARMAgeddon. Attacking client devices with Karma. In its pure form, this attack is implemented very rarely and only by most resolute hackers. However, KARMA is often used to attract clients in combination with other attacks (e.g. such popular hacking utilities as EAPHammer, hcxdumptool, Wifiphisher, and others implementing the RoqueAP vector).

Importantly, the KARMA technique is included in most of these utilities by default. Therefore, the chance to catch a hacker increases even when other attacks are delivered against your Wi-Fi.

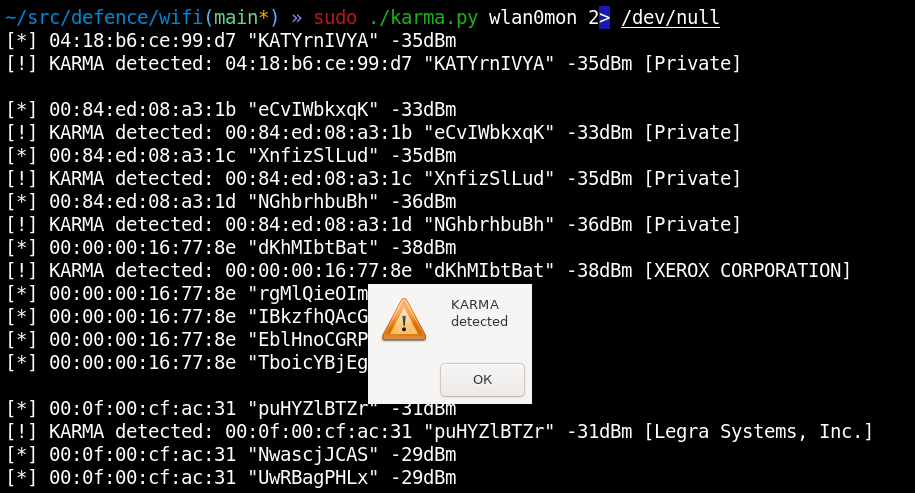

It’s quite easy to detect a KARMA attack. All you have to do is send a Probe request with a randomly generated network name: in theory, no one should respond to such requests except for specially deployed rogue access points:

defence/wifi/karma.py#!/usr/bin/python3from scapy.all import *from threading import Threadfrom mac_vendor_lookup import MacLookup # pip3 install mac-vendor-lookupfrom random import choicefrom string import ascii_lettersfrom time import sleepfrom sys import argvfrom os import systemiface = argv[1]conf.verb = 0oui = MacLookup()alerts = []def alert(ap, essid, signal): if ap in alerts: return print(f'[!] KARMA detected: {ap} "{essid}" {signal}dBm [{oui.lookup(ap)}]') system("zenity --warning --title='KARMA detected' --text='KARMA detected' &") #system("echo 'KARMA detected' | festival --tts --language english") alerts.append(ap)def probe_request(essid): source = "00:11:22:33:44:55" target = "ff:ff:ff:ff:ff:ff" radio = RadioTap() probe = Dot11(subtype=4, addr1=target, addr2=source, addr3=target, SC=0x3060)/\

Dot11ProbeReq()/\

Dot11Elt(ID='SSID', info=essid)/\

Dot11Elt(ID='Rates', info=b'\x8c\x12\x98\x24\xb0\x48\x60\x6c')/\

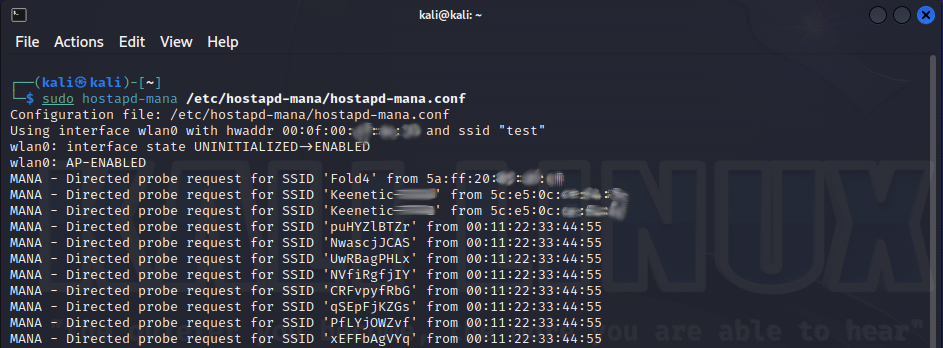

Dot11Elt(ID='DSset', info=int(36).to_bytes(1,'big')) return srp1(radio/probe, iface=iface, timeout=0.1)def rand(size): return "".join(list(map(lambda _:random.choice(ascii_letters), range(size))))while True: essid = rand(10) probe_resp = probe_request(essid) if probe_resp: signal = int(probe_resp[RadioTap].dBm_AntSignal) if hasattr(probe_resp[RadioTap], "dBm_AntSignal") else 0 ap = probe_resp[Dot11].addr2 print(f'[*] {ap} "{essid}" {signal}dBm') alert(ap, essid, signal) sleep(1)Imagine a situation: the hacker starts a program to attract clients and capture their WPA PSK passwords (i.e. delivers a half-handshake attack)…

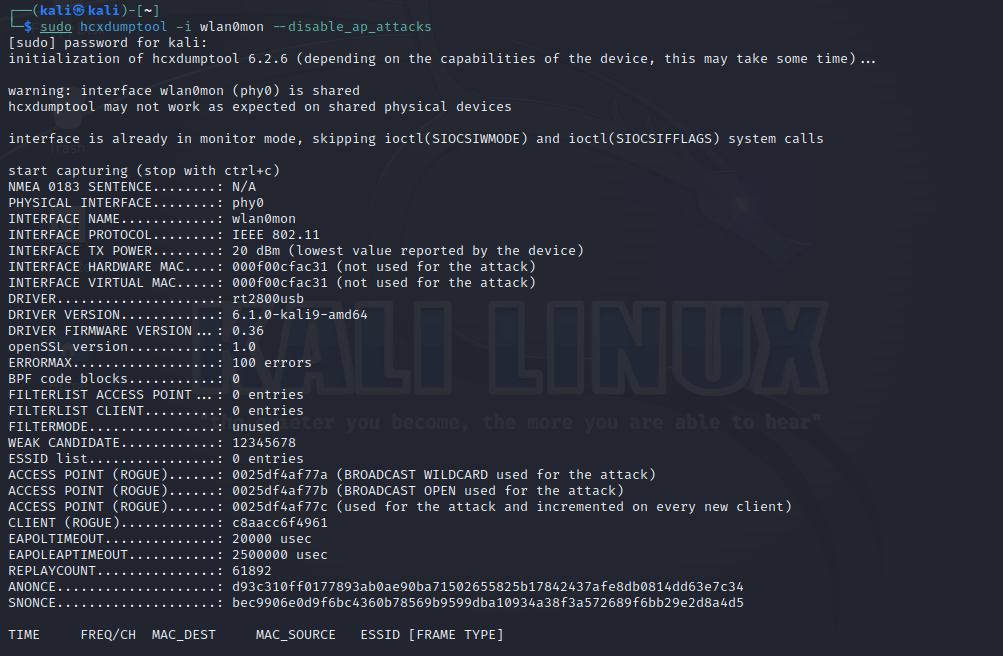

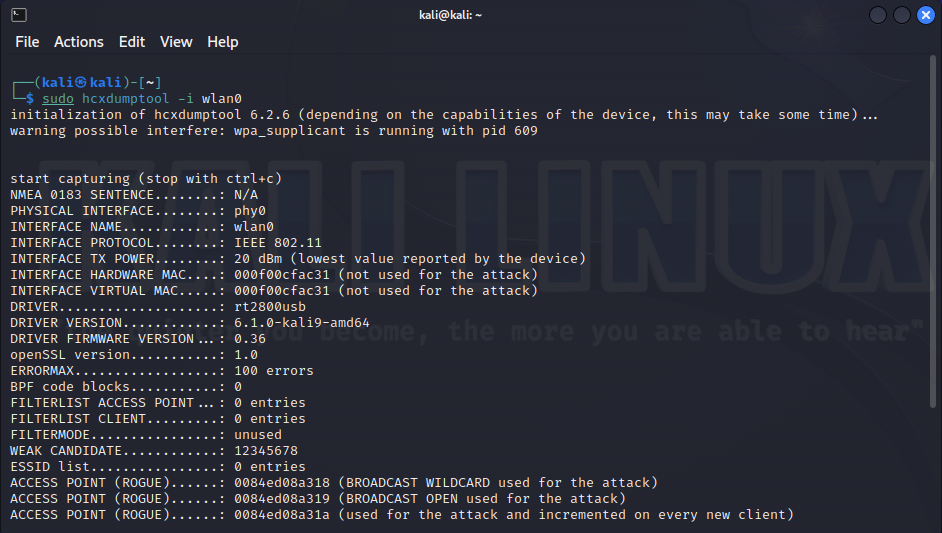

…or runs hcxdumptool without parameters to capture PMKID…

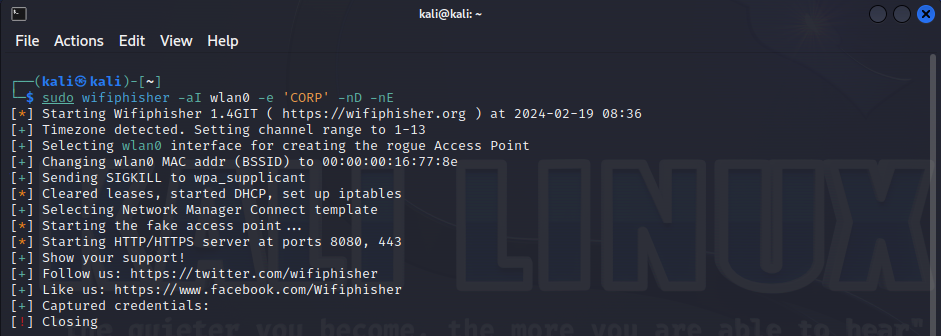

…or waits for clients to connect to an open access point…

…or deploys an access point for WPA Enterprise attacks…

….or simply performs an Evil Twin attack.

And in each case, you instantly detect the attacker.

You can see a Probe response to a random network name, as well as the signal strength of the responding rogue device. A legitimate access point won’t respond to such a request.

The above attacks have one common feature: all of them use the KARMA technique to attract clients. And most hackers aren’t even aware of this…

Conclusions

The “Self-defense for hackers” trilogy comes to an end. Now you know that many attacks can be detected by ordinary users who don’t have privileged access to the corporate infrastructure and just monitor certain events. You’ve learned that many attacks believed to be silent aren’t truly covert and leave distinctive traces.

The source code for all tools presented in this series of articles is available in my GitHub repository. The above-discussed attack detection techniques can be combined with existing defense mechanisms to make your corporate network even more secure.

Regardless of attacker’s experience and skills, chances are high that the bastard makes a blunder and gets caught. And if your infrastructure implements advanced monitoring, the hacker simply has no chance!

Good luck!