Why Is Wardriving Cool?

iPass has some interesting statistics on the growth of Wi‑Fi hotspots worldwide. Just look at it: since 2013, the number has grown by almost 900%. You can see roughly the same trend on WiGLE, which collects information about public access points.

Wi‑Fi is basically everywhere now; in any reasonably large city the 2.4 GHz band is completely saturated. Moscow, by the way, recently ranked second in the world for public Wi‑Fi coverage, which, as a Muscovite and a fan of Wi‑Fi hacking, makes me incredibly happy. I’ll talk another time about the role played by the MosMetro_Free and MT_FREE SSIDs.

Meanwhile, the Wi-Fi Alliance says this is just the beginning. By 2020, we’ll see 38.5 billion connected devices, with new standards geared toward low power and IoT gradually entering everyday use; we might even see meaningful cross‑pollination with LTE in the form of LTE-U, and so on.

Bottom line, you get it: a specialist who really knows the security side of all this won’t be out of a job. 🙂

warning

According to clause 4.1.1 of PCI DSS v. 2, the security of Wi‑Fi access points must be audited on a regular basis. The only proper way to do this is to use the same tools that are employed in real-world attacks. This article is for informational purposes and is intended for information security professionals and those aspiring to enter the field.

What Wi‑Fi standards exist?

You might be surprised, but Wi‑Fi doesn’t only operate in the 2.4 and 5 GHz bands. The “802.11” label actually covers a whole family of standards for device communication on a wireless LAN. They can use a variety of carrier frequencies. Here’s the list:

- 900 MHz — 802.11ah;

- 2.4 GHz — 802.11b, 802.11g, 802.11n, 802.11ax;

- 3.6 GHz — 802.11y;

- 4.9 GHz — 802.11j;

- 5 GHz — 802.11a, 802.11n, 802.11ac, 802.11ax;

- 5.9 GHz — 802.11p;

- 45 GHz — 802.11aj;

- 60 GHz — 802.11aj, 802.11ay.

If you want to brush up on the fundamentals, make sure to browse the IEEE 802.11 page on Wikipedia; if that’s not enough, go straight to the source and start digging into the standards themselves.

Which devices are suitable for wardriving?

The most important decision isn’t the specific model, but the type of device. You can choose from USB adapters (aka dongles or “sticks”; in some slang they’re called “cards”), Wi‑Fi routers, and microcontrollers with Wi‑Fi support. You can also use a phone or tablet, but you’ll usually get much better results when paired with an external adapter.

Why do so many just use a USB Wi‑Fi dongle?

It’s convenient, familiar, and usually cheaper than a router. There’s a good selection of well-proven adapters that support monitor mode (that’s the mode you’ll need to run attacks). In short, for beginners I’d recommend getting a USB Wi‑Fi “dongle” — it’ll come in handy more than once.

Can’t I just hack Wi‑Fi with my laptop’s built‑in adapter?

Hate to disappoint you, but the Wi‑Fi chipsets used in most laptops can’t be switched into monitor mode, so there’s not much to do there. And even if they could, the built‑in laptop antenna usually has limited range, and there’s nowhere to hook up an external one.

Where to start when choosing an adapter?

There are countless options, but not all of them are suitable for hacking. I recommend starting with WikiDevi to check the list of recommended adapters. You can also find plenty of information on the WirelesSHack site in the Wi‑Fi and Wireless section. The main things to look for are support for monitor mode and the ability to connect an external antenna—without one, you can forget about any real range. And of course, it’s best to pick an adapter with a well‑proven chipset.

Who are the major Wi‑Fi chipset vendors?

The main Wi‑Fi chip vendors are Qualcomm Atheros, Broadcom, Realtek, and MediaTek (formerly Ralink). Among them, Atheros is widely regarded as the best choice for wireless hacking and pentesting. For example, Ubiquiti primarily uses Atheros chipsets in its professional-grade devices, and most long-distance Wi‑Fi records have been set using Ubiquiti equipment.

Which adapter should I get?

Everyone is free to choose what they like, but lately I’ve been recommending the TP-Link WN722N to beginners and only that. There are several reasons: it’s inexpensive, widely available (you can find it in most computer stores), supports the necessary modes, and is built on mac80211 (the de facto standard for Wi‑Fi driver stacks). The WN722N has firmware source code and open-source drivers, which is great if you want to make your own modifications. I’ll also note its stability and modest power draw (0.5 A at peak). That makes it feasible to use with mobile devices over an OTG cable—this card is supported in Kali NetHunter. With the TP-Link WN722N you can scan the spectrum and carry out some advanced 802.11 attacks. In short, it has everything you’re likely to need.

A reader’s clarification

After the article was published, a reader by the handle InfiniteSuns sent an update: the 722N adapters have recently received a second hardware revision using the RTL8188EUS chipset.

So, what we said about Atheros only applies to the 722N, revision 1.x. For our purposes, these are the adapters you should be looking for.

So what about the legendary Alfa?

Many newbie wardrivers try to pick up an “Alfa,” meaning one of Alfa Networks’ Wi‑Fi adapters. But the company makes a lot of models on very different chipsets, so the “real” Alfa can mean different things. For me—as for many others—that’s the Alfa AWUS036H. Back in the day it was the most coveted card because it has a built-in RF power amplifier. The rest of Alfa’s lineup is also well engineered and well built, but I wouldn’t call them unique.

Unfortunately, the Alfa AWUS036H’s best days are behind it. It’s built on the Realtek RTL8187L chipset, which doesn’t support 802.11n or access point (AP) mode. It still shines in WPS attacks under weak signal conditions, but otherwise there’s nothing particularly special about it. And you can’t really use it with a smartphone—the power amplifier draws too much current.

There are Alfa adapters labeled “Long-Range.” They don’t include a power amplifier, but they do use quality RF filters and the TeraLink chipset, which has proper driver support. Worth considering as an option.

Do I need a special USB cable?

Before you plug the adapter into your computer, make sure it has stable power to avoid dropouts. This matters for any RF device, and the Alfa AWUS036H in particular is known for its higher power draw. Not all USB cables are equal—the current they can deliver depends on build quality (thicker cables are often a decent proxy). So if you’ve bought a good Wi‑Fi adapter, don’t hook it up with a random cheap cable.

Do I need USB 3.0, or is USB 2.0 enough?

Most adapters come with a USB 2.0 interface because USB 3.0 introduces significant constraints. Major chip vendors (like Atheros) only support 5 GHz on PCIe cards—and those are what I recommend for 5 GHz work. For everything else, USB 2.0 is perfectly adequate.

Can you find a decent adapter on AliExpress?

Chinese marketplaces are full of various adapters, including clones of well-known brands like Alfa. But you need to be very careful when choosing: the listed specs often don’t match reality, and even the chip may be a different revision than the one advertised. A Hacker magazine author took a close look at several such options in an article titled “Choosing a budget adapter for Wi‑Fi hacking.” As a result, they found a decent external antenna bundled with a far-from-stellar adapter (the Netsys 9000WN), as well as a few extremely cheap adapters. In short, if you’re after savings and a bit of adventure, keep digging—you might stumble on something interesting. And don’t forget to share your find in the comments!

When does it make sense to use a router instead of a USB Wi‑Fi adapter?

When you use a USB Wi‑Fi dongle, the software has to run on a computer, which isn’t always convenient. A WPS attack can drag on for up to eight hours, and out in the field—especially in our harsh climate—wardriving while lugging a laptop around is no fun.

It makes sense to offload this work to a separate device, and a router is exactly such a self-contained box. You just need to choose a suitable model and load it with a custom firmware. Hacker-oriented builds are usually based on OpenWrt and bundle the necessary tools: Aircrack-ng, Reaver, PixieWPS, and other utilities. As for turnkey options, there’s essentially just one so far—the well-known “Pineapple,” aka the WiFi Pineapple.

There are entire classes of attacks you can’t pull off with a USB Wi‑Fi dongle. Take the KARMA attack, later popularized as MANA—an “evil twin” access point. If you try to run it with a dongle like the TP‑Link WN722N, you’ll run into a seven‑client limit hardcoded in the firmware. The real reason is the adapter just doesn’t have enough onboard memory.

What exactly is this “Pineapple” router?

WiFi Pineapple began as a custom firmware project for an Alfa Networks router, originally called Jasager. Under the Hak5 team’s guidance, it evolved over the years into a dedicated, highly specialized device that not only captures Wi‑Fi connections but also enables subsequent man‑in‑the‑middle (MITM) attacks on the network. It comes in two variants: the standalone WiFi Pineapple TETRA and the USB‑form‑factor WiFi Pineapple NANO.

So why not just buy a WiFi Pineapple?

The “Pineapple” is definitely an interesting device that deserves its own write-up. It has a sleek, user-friendly web interface and is ready to use out of the box. But it isn’t cheap (the NANO is 99 USD and the TETRA is 199 USD), and you can’t order it directly from Russia.

Which other routers should you consider?

Routers come in all shapes and sizes, and you can check OpenWrt support on the project’s site. Among desktop models, a solid pick is the TP-Link TL-WDR4300 on an Atheros chipset; it can operate simultaneously in the 2.4 and 5 GHz bands. But it’s not something you’d want to take into the field.

Lately I’ve been impressed by the offerings from the Hong Kong company GL.iNet, built around the Domino Core SoM. GL.iNet provides a full lineup—from bare boards and components to fully assembled routers. I picked up a GL-MiFi for $99. It stands out with the following advantages:

- Built‑in battery (unlike the WiFi Pineapple)

- Optional 4G modem at purchase time: Quectel EC25 (https://osmocom.org/projects/quectel-modems/wiki/EC25), which is hackable in its own right

- Supports external antennas via U.FL connectors on the board

- Can double as a power bank to charge a mobile phone

- By the standards of Chinese vendors, GL.iNet is unusually solid—they even provide their own firmware with built‑in Tor support

GL.iNet gear has already won over the hacker community, and custom firmware with homebrew “Pineapple” functionality has started to appear. I’ll brag a bit myself: I’ve put together a unified repository of various “Pineapple” DIY projects that makers and tinkerers may find useful.

|

|

| GL-MiFi, front and back | |

Which routers are best avoided (or used with caution)?

While there are plenty of routers to choose from, not just any will do for hacking. As with adapters, I prefer Atheros‑based hardware. That includes a lot of TP‑Link gear, which has long been popular with hackers. Models like the TL‑WR703N, TL‑MR3020, and TL‑MR3040 were, until fairly recently, widely used as platforms for custom firmware and mods geared toward hacking.

Building on those, hobbyists assembled their own “pirate” builds and Wi‑Fi Pineapple clones with Karma attack support. The USB port lets you plug in either a 3G/4G modem or a standard flash drive loaded with a solid software toolkit, and the ability to run Python + Scapy will appeal to many fans of network tinkering.

However, the limited flash and RAM in these models is a serious barrier to building more capable firmware. So unless you’re ready to mod them, I wouldn’t recommend buying them today.

Can you upgrade your existing router?

Small ROM and RAM sizes aren’t a death sentence for a device—you can desolder and replace them fairly cheaply. The chips themselves cost next to nothing. For the ROM, I’d recommend the Winbond W25Q128FV with 16 MB of flash memory.

It gets even better with RAM: you might not need to buy anything at all. You can salvage RAM chips from old DDR1 modules (you did keep them when you junked that old tower, right?). And if you don’t have a stash of vintage parts and grandpa won’t let you strip his PC, that’s still fine. Enterprising Chinese vendors sell ready-made replacement kits—look for RAM in 66‑pin TSOP‑II packages.

Before expanding the memory, you should reflash the router. The stock firmware on many routers often contains hard‑coded addresses that won’t be valid once you increase the amount of RAM.

If you’ve already bricked your router, U-Boot can save you. With TP-Link routers, you just need to type the magic letters tpl over UART during boot, and the device will drop you into U-Boot instead of trying to load a crashing kernel.

What do you need to hack Wi‑Fi with a smartphone?

When you can’t break out the antennas and a laptop, there’s a fallback: use a mobile phone for pentesting. The process is covered in detail in the article “Hacking Wi‑Fi with a Smartphone.” In short, you’ll need the Kali NetHunter distribution, one of the compatible phones with a supported firmware, and of course an external USB adapter connected via an OTG cable.

As a dongle, you can use the already-mentioned TP-Link WN722N—among popular models it’s the only one with low enough power draw to plug into even low-power devices. The pricier, more feature-packed Alfa adapters can also be made to work with a phone, but not every model and not with every phone. A high-power “card” may fail to work or will just drain the phone’s battery dry. As a result, people have started rigging setups with external battery packs and even solar chargers.

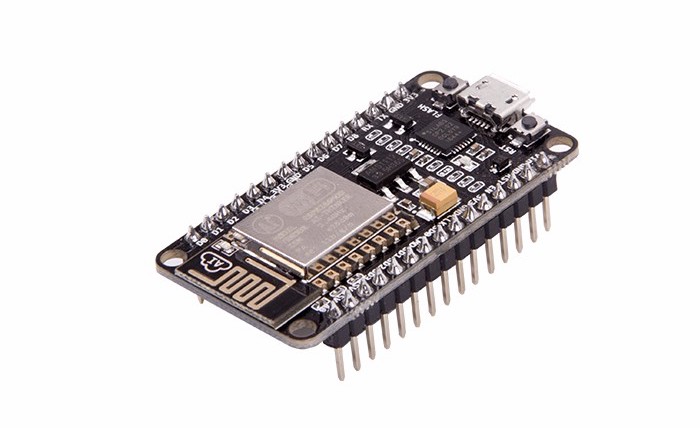

Is the ESP8266 suitable for wardriving?

With the rise of IoT, the tiny ESP8266 wireless controller became widespread, and hackers started wondering how to enable monitor mode on it. Eventually, that was achieved. Unfortunately, true monitoring and packet injection on this chip aren’t possible due to a hardware limitation: a 128-byte buffer. That’s not nearly enough to reliably capture handshakes. However, it’s sufficient for sending deauthentication frames. I’ve put together a collection of various ESP8266 projects (including deauth tools) on my GitHub. I’d also like to draw your attention to a Wi‑Fi positioning project based on the ESP8266.

What other microcontrollers can I use?

Monitor mode is available on the TI CC3200 as part of their proprietary RFSniffer technology. It’s worth noting that monitor capability on TI/Chipcon radios has already led to tools like Yard Stick One/RFCat and Ubertooth, aimed at hacking ISM and Bluetooth respectively. How practical is the CC3200 in the real world? With that question in mind, I bought a dev board, but haven’t had time to dig in yet. Maybe once I do, I’ll have material for an interesting piece in Hacker magazine!

So, what should a beginner buy?

If you need a place to start, grab a TP-Link WN722N. It’s a workhorse you’ll use again and again—you can hook it up to a laptop, a tablet, or even a router. There’s an entire class of attacks that only work with an Atheros chipset—various custom and advanced techniques.

A router shines when you need to kick off a scan and leave it running for a long time. If you often work in the field, you can do what I do and use a GL-MiFi—it’s handy not just for hacking, but also for more mundane tasks like sharing a mobile data connection.

What types of antennas are there?

One standout item on the hardware list is the antenna—or rather, antennas. An antenna’s shape embodies mathematical design, which is why it’s often patented (and the Chinese, of course, know this and, as usual, resort to piracy).

There are several primary types of antennas, and each is suited to different tasks. Based on their radiation pattern, they are classified as:

- omnidirectional (whip, dipole)

- directional (Yagi–Uda, a.k.a. “wave-channel”)

- semi-directional (panel, sector, parabolic dish)

The most versatile option, of course, is the whip antenna—the kind that sticks out of most home routers.

As you can see, many router antennas have helical turns, and that’s not by accident. The Wi‑Fi signal is radiated primarily in the plane of those turns. So be mindful when setting up your home router—orient the antenna planes to cover your own floor, not the apartments above or below; your neighbors won’t benefit from it anyway. Read more about this in the article “Wi‑Fi to the Max: How to improve connection quality without additional cost.”

So, which antenna should you get?

An omnidirectional whip antenna is great when you need to run in AP mode—sharing internet access. When you’re targeting a specific access point for compromise, you use directional antennas. My two main antennas are a whip for internet sharing and a high-gain directional antenna with a large reflector.

How do I mount the antenna?

Since a directional antenna needs to be rigidly secured, the question is what to mount it with. I recommend using a camera or telescope tripod. Since I only have one tripod, I can’t advise on specific brands or models. I chose mine based on “the most degrees of freedom for a reasonable price.” And of course, pay attention to the load capacity the tripod can handle and its build quality.

The holy grail is a telescope mount that can steer itself via commands over USB or a serial (COM) port. These little guys aren’t cheap, though. The upside is you can talk about scanning not just the spectrum, but the terrain as well. 🙂

What else can we tinker with?

Just three years ago, Gleb Cherbov and I were up late hacking a wireless doorbell to introduce readers of Hacker magazine to one of the first HackRF (Jawbreaker) units in Russia. At 433 MHz, a simple sniff-and-replay was enough (and still is) to make the neighbors’ doorbell ring endlessly. It hasn’t been that long, and now we’re reading news about great write-ups on hacking doorbells over Wi‑Fi.

Forget phone calls—these days even Japanese SUVs can be unlocked over Wi‑Fi. And that’s just the beginning. Around 90% of new cars now ship with built‑in hotspots. The usual routers, printers, cameras, and other IoT stuff hardly seem worth mentioning anymore. If you’re itching for something new, there’s always nRF24 and NFC. Bottom line: you won’t be bored.