I often hear that among all types of attacks against organizations, social engineering is supposedly the most destructive and dangerous. So why doesn’t every infosec conference give it a dedicated track?

In the Russian-language internet, most examples are pulled from foreign sources and Kevin Mitnick’s stories. I’m not claiming such cases are rare on Runet; they just don’t seem to get discussed. I set out to assess how dangerous social engineering really is and to gauge the potential fallout if it were used at scale.

Social engineering in infosec and pentesting is usually associated with a pinpoint attack against a specific organization. In this set of case studies, I want to explore several ways social engineering can be applied at scale—either indiscriminately, or mass-targeted at organizations in a particular sector.

Let’s define terms so it’s clear what I mean. I’ll use the term “social engineering” to mean “a set of methods for achieving an objective by exploiting human weaknesses.” It’s not always illegal, but it definitely has a negative connotation and is associated with deception, fraud, manipulation, and similar tactics. By contrast, little psychological tricks to talk your way into a discount at a store aren’t social engineering.

Let me say up front: in this field I acted solely as a researcher—I did not create any malicious sites or files. If anyone received an email from me with a link, the site it pointed to was safe. At worst, it might have included Yandex.Metrica analytics for user tracking.

You’ve probably seen spam with “completion certificates” or contracts booby‑trapped with Trojans. That kind of blast doesn’t surprise accountants anymore. And those pop-ups “recommending” you install a video plugin—been there, done that. I’ve come up with a few less obvious scenarios and offer them here as food for thought. I hope they won’t serve as a how-to, but instead help make the RuNet safer.

A “Verified Sender”

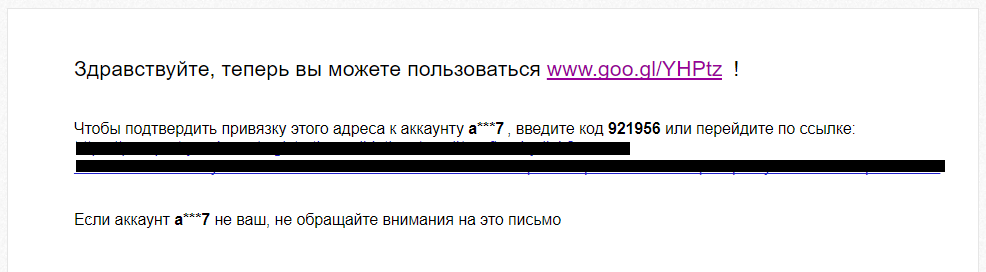

Sometimes site administrators forget to sanitize the “Name” field in a registration form (for example, when signing up for a newsletter or submitting a request). Instead of a name, you can insert arbitrary text—sometimes kilobytes of it—and a link to a malicious site. In the email field, you enter the victim’s address. After registration, that person receives an email from the service: “Hello …,” followed by your text and link. The legitimate service’s message ends up at the very bottom.

How do you turn this into a weapon of mass disruption? Easy. Here’s a case from my own experience. In December 2017, one search engine had a flaw that let you send messages via the “add a recovery email” form. Before I submitted a bug bounty report, it was possible to send 150,000 messages per day—you just needed to slightly automate filling out the form.

This trick lets attackers send fraudulent emails from a site’s real support address—complete with valid digital signatures, encryption, and so on. The catch is that the entire top portion of the message is actually written by the attacker. I’ve received such emails myself, not only “from” big names like booking.com or paypal.com, but also from lesser-known sites.

In my test, about 10% of recipients clicked the link. No further comment.

And here’s the April 2018 “trend.”

Google Analytics Emails

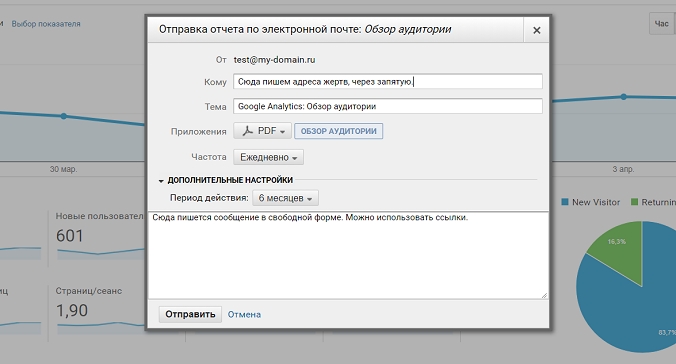

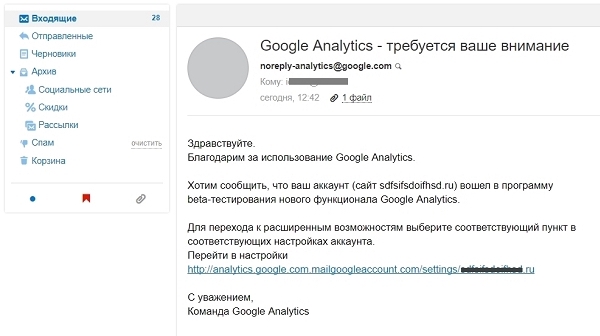

Let me share a very recent case—from April 2018. I started receiving spam at several of my addresses from the Google Analytics sender noreply-analytics@google.com. After digging into it a bit, I figured out the method they were using to send it.

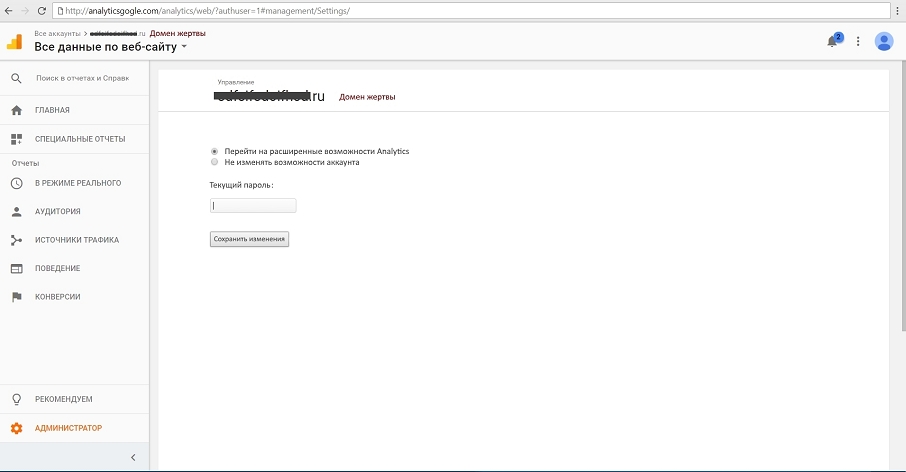

“How could this be used?” I thought. Here’s what came to mind: a scammer could, for example, craft a message like this.

If the user clicked the link, they’d be taken to a fake site and would enter their password.

This kind of password harvesting can be done not just in a targeted way, but at scale—you just need to automate the collection of domains from Google Analytics and the extraction of email addresses from those sites.

Curiosity

This trick for luring someone into clicking a link takes a bit of preparation. You set up a website for a fake company with a quirky, one-of-a-kind name that instantly catches the eye. Something along the lines of “Twist’n’Bend LLC”. Then you wait for the search engines to index it.

Next, come up with a pretext to send out congratulatory messages on behalf of that company. Recipients will immediately Google it and find our site. It’s best to make the greeting itself unusual so they don’t just dump the email into the spam folder. In a small test, I easily generated over a thousand click-throughs.

Fake Newsletter Subscription

Here’s a dead-simple way to get someone to click through to your site from an email. Write something like: “Thanks for subscribing to our newsletter! You’ll receive a daily price list for reinforced concrete products. Regards, …”. Then add an “Unsubscribe” link that points to our site. Of course, no one actually subscribed to this newsletter, but you’ll be surprised how many people rush to unsubscribe.

Email Harvesting

To build your own database, you don’t even need to write a custom crawler and scour sites for exposed addresses. A list of all Russian-language domains—currently about five million—is enough. Append info@ to each one, validate the resulting addresses, and you’ll end up with around 500,000 active inboxes. You can do the same with director, dir, admin, buhgalter, bg, hr, and so on. Draft a message tailored to each of these departments, send it out, and you’ll get hundreds to thousands of replies from employees in the corresponding fields.

What does it say?

To lure users from a forum or any site with open comments, you don’t need flashy copy—just post an image. Pick something eye-catching (a meme works) and compress it so heavily the text becomes unreadable. Curiosity reliably makes people click the picture. I ran an experiment and got about 10,000 click-throughs this way. I also know of a case where a team adapted this method to deliver trojans via LiveJournal.

What’s Your Name?

Getting a user to open a file—or even a macro-enabled document—isn’t that hard, despite widespread awareness of the risks. In a mass mailing, even just knowing the recipient’s name significantly increases the chances of success.

For example, we can send an email like “Is this address still active?” or “Could you please share your website URL?” In at least 10–20% of the replies, we’ll get the responder’s name (this is more common at larger companies). After a while, we follow up with something like, “Alyona, hello. What’s going on with your website (photo attached)?” or “Boris, good afternoon. I can’t figure out the price list. I need item 24. I’m attaching the price list.” And the “price list” contains the classic line: “To view the contents, please enable macros…,” with all the predictable consequences.

In short, individually addressed messages are opened and acted on about an order of magnitude more often.

Reconnaissance at Scale

This scenario isn’t so much an attack as preparation for one. Suppose we want to learn the name of a key employee—for example, the accountant or the head of security. That’s easy enough to do by emailing someone likely to have that information with a message like: “Could you please tell me the director’s patronymic and the office hours? We need to send a courier.”

We ask about office hours to throw them off, and asking for a patronymic is a trick that keeps us from revealing we don’t know their first and last name. Both are likely to show up in the target’s reply: people usually write out their full name. In my research, this approach let me collect the full names of more than two thousand directors.

If you need to find out the boss’s email, you can just write to the secretary: “Hello. I haven’t been in touch with Andrey Borisovich for a while—does his address andrey.b@company.ru still work? I haven’t received a reply from him. Roman Gennadievich.” The secretary sees an address fabricated from the director’s real name and the company’s domain, assumes it’s plausible, and provides Andrey Borisovich’s actual address.

Personalized Evil

If you need to get a large number of organizations to respond to an email, start by hitting their pain points. For example, send retailers a product complaint and threaten escalation: “If you don’t resolve this, I’ll take it to the director! What is this you delivered to me (photo attached)? The archive password is 123.” To auto repair shops, blast out a photo of a fault and ask if they can fix it. For construction firms, send a “house project.” In my small study, at least 10% of recipients responded to messages like these.

Your Website Is Down

A database of websites with their owners’ email addresses can be easily turned into clicks to any site you want. You send emails saying, “For some reason, the page on your site www.site.ru/random.html isn’t working!” And the classic trick: the link text shows the victim’s own site, but the actual link points to a different URL.

Dynamic landing page

You’ll need to prepare for this approach. Build a one-page site and style it to look like a news outlet. Install a script that changes the page’s text based on the link the visitor clicked to get there.

We’re sending a campaign to a database that includes email addresses and company names. Each message contains a unique link to our news site, for example news.. The 1234 parameter is mapped to a specific company name. A script on the site detects which link the visitor used and displays in the content the company name associated with that email record in the database.

When the employee visits the site, they’re greeted by a headline like “Company [victim’s name] is at it again.” Below it is a short “news” blurb full of fabrications, which includes a link to an archive of supposed exposés—actually a Trojan.

Conclusions

It’s clear that spray-and-pray tactics won’t work against large enterprises—they require a tailored, targeted approach. Small businesses, however, where many have little to no awareness of social engineering, can easily fall victim to these attacks.