warning

Overly aggressive activity in the RF spectrum requires proper authorization and licensing; ignore that and you’re automatically in the “bad guys” category (details — here).

What is an IMSI catcher?

It’s a device (about the size of a suitcase, or even just a phone) that exploits a design trait of mobile phones: they prefer to connect to the cell tower with the strongest signal (to maximize signal quality and minimize their own power use). In GSM (2G) networks, only the handset is required to authenticate (the cell tower doesn’t), which makes it easy to deceive the phone, including forcing it to disable encryption. By contrast, UMTS (3G) mandates mutual authentication; however, this can be bypassed by pushing the phone into GSM compatibility mode, which most networks still support. 2G networks remain widespread—operators use GSM as a fallback where UMTS isn’t available. More in-depth technical details of IMSI catching are available in the SBA Research report. Another substantive overview—now a go-to reference for modern cyber counterintelligence—is “Your Secret StingRay Is No Secret Anymore,” published in fall 2014 in the Harvard Journal of Law & Technology.

When did the first IMSI catchers appear?

The first IMSI catchers appeared back in 1993 and were large, heavy, and expensive. “Long live our homegrown microchips—with fourteen pins… and four carrying handles.” There were only a handful of manufacturers, and the high cost meant only government agencies could use them. Today, they’re getting cheaper and less bulky. For example, Chris Paget built an IMSI catcher for just $1,500 and presented it at DEF CON in 2010: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DU8hg4FTm0g. His version uses a software-defined radio and free open-source software: GNU Radio, OpenBTS, Asterisk. All the information a developer needs is publicly available. And in mid-2016, hacker Evilsocket published his own take on a portable IMSI catcher for only $600.

How IMSI catchers hijack your phone’s connection

- They trick your phone into thinking it’s the only network available.

- They can be configured so you can’t place a call unless it goes through the IMSI catcher.

- For more on this “monopolization” tactic, see SBA Research’s paper: IMSI-Catch Me If You Can: IMSI-Catcher-Catchers (https://www.sba-research.org/wp-content/uploads/publications/DabrowskiEtAl-IMSI-Catcher-Catcher-ACSAC2014.pdf).

The selection of off‑the‑shelf IMSI catchers is impressive. What about DIY builds?

As of 2017, resourceful engineers can build IMSI catchers from off-the-shelf high-tech components and a high-gain antenna for no more than about $600 (see hacker Evilsocket’s IMSI catcher build). That’s for relatively stable IMSI catchers. There are also experimental, cheaper setups that are less reliable. For example, at Black Hat 2013, a version of an unstable IMSI catcher was presented, with total hardware costs of $250. A similar build would be even cheaper today.

If you also consider that modern Western high-tech military systems use open hardware architectures and open-source software (now a must to ensure interoperability across military hardware–software systems), developers interested in building IMSI catchers have every advantage. You can read more about this trend in military high tech in the journal Leading Edge (see the article “Advantages of SoS Integration” (http://www.navsea.navy.mil/Portals/103/Documents/NSWC_Dahlgren/LeadingEdge/CSEI/CombSys.pdf), published in the February 2013 issue). Not to mention that the U.S. Department of Defense recently signaled its willingness to pay $25 million to a contractor to develop an effective radio identification system (see the April issue (http://digital.militaryaerospace.com/militaryaerospace/) of the monthly magazine Military Aerospace, 2017). One of the primary requirements for this system is that its architecture and components must be open. In short, open architectures are now a prerequisite for interoperability in military hardware–software systems.

That’s why IMSI-catcher manufacturers don’t need deep technical expertise—they just need to combine existing off-the-shelf solutions and package them into a single box.

What’s more, modern microelectronics—getting cheaper at a breakneck pace—lets you cram a DIY build not just into a single box but even into a single chip (see the SoC concept) and, beyond that, set up an on‑chip wireless network (see the NoC concept at the same link), which is replacing traditional data buses. And IMSI catchers are hardly exotic anymore, given that you can now find openly available technical details on the hardware and software components of the ultramodern F‑35 fighter.

Could I be a victim of “incidental interception”?

It’s entirely possible. By impersonating a cellular base station, IMSI catchers intercept all local traffic—which, among other things, sweeps up the conversations of innocent bystanders (see “revelations of Big Brother’s older sister”: https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/national-security/meet-the-woman-in-charge-of-the-fbis-most-contentious-high-tech-tools/2015/12/08/15adb35e-9860-11e5-8917-653b65c809eb_story.html?utm_term=.fee4696985df). That’s the favorite argument of “privacy advocates” who oppose law enforcement’s use of IMSI catchers, even though agencies deploy this high-tech gear to track criminals.

How can an IMSI catcher track my movements?

- Most often, IMSI catchers used by local law enforcement are deployed for location tracking.

- Knowing the target handset’s IMSI, the operator can program the IMSI catcher to engage the device whenever it comes within range.

- After it connects, the operator uses radio-frequency mapping to determine the target’s direction.

Can they listen in on my calls?

- It depends on the IMSI catcher in use. Basic models simply log something like: “this handset is at this location.”

- To intercept calls, an IMSI catcher needs additional capabilities that vendors sell as paid add-ons.

- 2G calls are easy to tap. IMSI catchers for 2G have been available for more than a decade.

- The price of an IMSI catcher depends on the number of channels, operating bands, supported encryption, encoding/decoding throughput, and which radio interfaces need to be covered.

Can they install software on my phone?

An IMSI catcher collects the IMSI and IMEI from your device. That lets its operator know which phone model you use, and sometimes even where you bought it. With the model number in hand, it’s easier for them to push a firmware update specifically tailored to that handset.

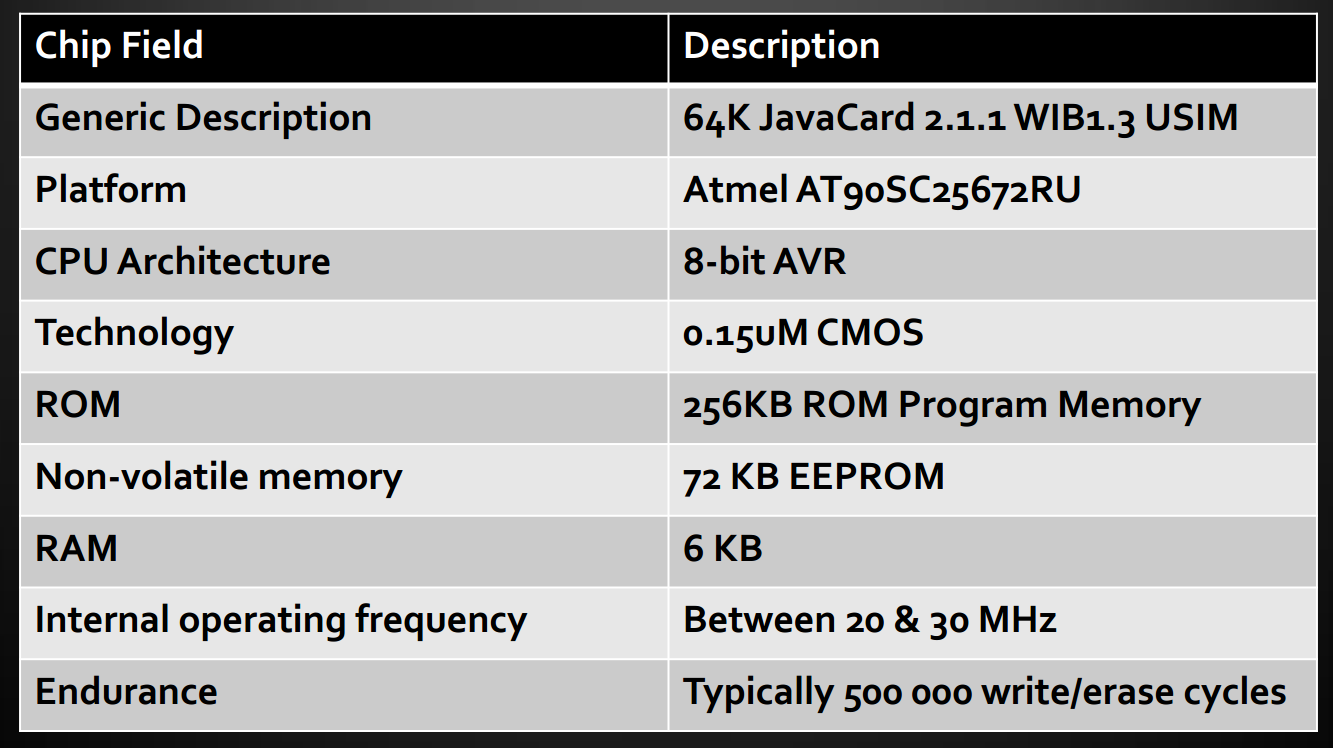

Besides, your SIM card is a computer in its own right. It can run simple programs without interacting with your phone at all—and without needing to know your phone’s model or operating system.

Mobile carriers can update a SIM card’s software over the air—and do it silently, without alerting the user. So if an IMSI catcher impersonates a carrier, it can do the same. The SIM card’s onboard controller (via SIM Toolkit) can: send and receive data, open URLs, send SMS, place and answer calls, connect to and use information services, handle events like “call connected” or “call dropped,” and issue AT commands to the handset.

The SIM card’s onboard computer can do all of this quietly—without the phone showing any sign of activity. You can learn more about the secret life of your SIM card from Eric Butler’s presentation delivered at DEF CON 21 (2013).

We all know public Wi‑Fi is risky. If I stick to LTE only, can I still be intercepted?

First, even if your phone is set to LTE and shows it’s connected, that doesn’t necessarily mean it really is. With a well-configured IMSI-catcher, your phone can display a normal 3G or 4G connection while being quietly forced back to the much weaker 2G encryption.

Some phones, even in LTE mode, execute commands without prior authentication, despite the LTE standard requiring it (see the SBA Research report mentioned earlier in the article).

Moreover, because the LTE radio interface wasn’t built from scratch but evolved from UMTS (itself an upgraded GSM interface), its architecture isn’t without flaws. In addition, despite the wide deployment of 3G and 4G, 2G networks still provide fallback connectivity when 3G/4G are unavailable.

Sure, you can set your phone to use 4G only, but 4G isn’t available everywhere, so your coverage will shrink significantly.

What if I’m a big‑shot banker (yes, we big‑shot bankers love Hacker magazine) and someone really, really wants to sniff my traffic?

The Universal Mobile Telecommunications System (UMTS, 3G) and Long Term Evolution (LTE, 4G) require mutual authentication, but even they aren’t immune to IMSI catchers. Such interception gear is, of course, considerably more expensive. One example is the VME Dominator from the U.S. company Meganet Corporation.

At DEF CON 22 (in 2014), hacker Justin Case gave a live demo of hacking the world’s most secure smartphone—the Blackphone. It took him just five minutes (see slides).

There’s also a system for intercepting LTE traffic that doesn’t rely on downgrade tricks; it works with a full-fledged LTE connection. In 2014, Tobias Engel presented it at the Chaos Computer Club’s annual congress, themed “A New Dawn.”

Ultimately, if someone has a “really, really strong urge to sniff” and a $100,000 budget to back it up, you pretty much can’t defend against it. All the most advanced components are available off the shelf. The U.S. Department of Defense even encourages this openness so that technology vendors compete to raise the bar on quality.

What data can still be exposed if I use HTTPS everywhere and two‑factor authentication?

HTTPS isn’t a silver bullet. You won’t hide from intelligence agencies. They can simply compel the provider to hand over its TLS/SSL keys, giving them access to all your data in transit. So unless you’re truly untraceable, I wouldn’t count on absolute privacy.

On April 14, 2017, WikiLeaks published six documents from the “Hive” project — tools for unauthorized access to encrypted HTTPS traffic that, until recently, had been used exclusively by CIA personnel. As of today, those tools are publicly available.

Given the scope of international intelligence agencies’ ambitions (see “Snowden’s Truth” at https://habrahabr.ru/post/272385/), and the fact that, thanks to Snowden and WikiLeaks (https://wikileaks.org/vault7/?marble9#Marble%20Framework), the CIA’s high-tech treasure trove now stands wide open, there’s every reason to assume that anyone might take an interest in your data: government services, commercial corporations, or even rowdy teenagers. Moreover, since the average age of cybercriminals has been steadily dropping (in 2015 the average fell to 17), we should expect that more and more intrusions will be carried out by those same teenagers—unpredictable and reckless.

How do you protect against interception?

IMSI catchers are becoming increasingly accessible, which is driving demand for countermeasures. There are both purely software and combined hardware–software solutions.

Among software solutions, there are many Android apps on the market, such as AIMSICD (interacts with the phone’s radio subsystem, attempting to detect anomalies) and FemtoCatcher (offers functionality similar to AIMSICD but is optimized for Verizon femtocells). Also noteworthy are GSM Spy Finder, SnoopSnitch, and Net Change Detector. Most of these are low quality. Moreover, several apps on the market generate a lot of false positives due to the insufficient technical expertise of their developers.

To work effectively, the app needs access to the phone’s baseband and radio stack, along with first-rate heuristics to tell an IMSI catcher from a misconfigured cell tower.

Among hardware/software solutions, four devices stand out: 1. Cryptophone CP500. Priced at $3,500 per unit. As of 2014, more than 30,000 crypto phones had been sold in the US, and over 300,000 in the rest of the world. 2. ESD Overwatch. A device featuring a three-component analyzer (see description below). 3. Pwn Pro. A device with a built‑in 4G module, announced at RSA Conference 2015; it costs $2,675. 4. Bastille Networks. A system that lists nearby wireless devices interacting with the RF spectrum (from 100 kHz to 6 GHz).

Can ESD Overwatch guarantee 100% protection?

In its basic configuration, ESD Overwatch includes a three-part analyzer that watches for three red flags. The first is a downgrade from the more secure 3G/4G networks to the less secure 2G. The second is when a call drops encryption, making interception much easier. The third is when a cell tower withholds the neighbor cell list (which phones use to hand off between nearby towers); IMSI catchers typically suppress alternatives to monopolize the device.

Keep in mind that even a three-pronged approach doesn’t guarantee 100% protection. There’s also a free app (available on Google Play) that claims to do the same job as CryptoPhone with ESD Overwatch — Darshak. Moreover, albeit rarely, there are cases where, even when all three indicators are present, no actual IMSI capture is happening. And of course, once IMSI-catcher developers hear about this three-part counter-surveillance method, they won’t hesitate to respond—this is an ongoing arms race.

Even the military can’t guarantee 100% protection, despite using the most advanced (as of 2016) PacStar-developed hardware/software suite IQ-Software. IQ-Software is a next-generation wireless tactical system for exchanging classified information with smartphones and laptops over Wi‑Fi and cellular radios. And it shouldn’t be a surprise that in modern military operations—the same smartphone you carry in your pocket is used, and not just for communications.

In the summer of 2013, the U.S. Air Force published the announcement “B-52 CONECT: A Reboot for the Digital Age.” The CONECT (Combat Network Communications Technology) upgrade will bring the B-52 strategic long-range bomber into the modern digital infrastructure, transforming this largely analog aircraft into a networked platform that can receive commands from a standard smartphone.

info

This is precisely why the military are highly invested in secure communications, but even they cannot achieve absolute protection.

Will IMSI-catchers keep eavesdropping on me if I change my SIM card?

An IMSI catcher grabs the IMSI from your SIM card and the IMEI from your phone, then stores both identifiers in a centralized database. As a result, swapping SIM cards or changing phones won’t help you avoid tracking.

Sure, if you get a new phone and a new SIM, the IMSI-catcher’s centralized database won’t have records for them. But the people you communicate with would also need new phones and new SIMs. Otherwise, cross-references in that centralized database will link you back, and you’ll end up on the IMSI-catcher’s list again.

In addition, an IMSI catcher can triangulate mobile devices within a specified area.

If I use CDMA, am I safe from IMSI catchers?

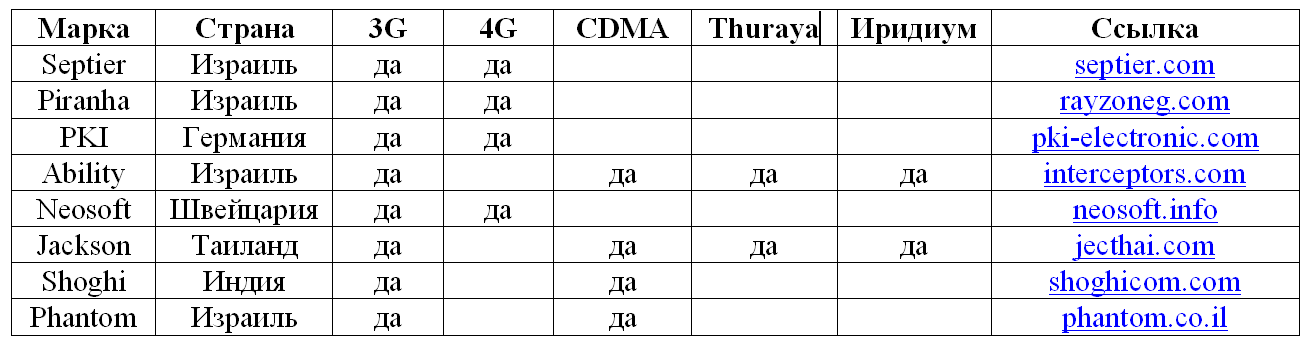

No, because the same vendors that build GSM IMSI-catchers also make CDMA models, and some even offer versions for Iridium (a global satellite communications operator) and Thuraya (a regional satellite phone operator covering Europe, Central Asia, Australia, and Africa). These include the Israeli lab Ability and Thailand’s Jackson Electronics.

Why do bad actors use IMSI catchers?

- To terrorize others by sending threatening text messages

- To monitor ongoing law-enforcement investigations

- For government, corporate, and domestic espionage

- To steal personal information transmitted over mobile phones

- To block a mobile user from contacting emergency services

How common are IMSI catchers today?

Aaron Turner, head of the IntegriCell research lab specializing in mobile device security, carried out his own independent investigation. Over two days of driving with a cryptophone (which monitors suspicious mobile activity), he came across 18 IMSI catchers, mostly near specialized government facilities and military bases.

At the same time, Turner won’t say whose IMSI-catchers these are—whether it’s the intelligence services doing the spying, or someone spying on the spies. The Washington Post reported on this back in 2014.

That same year, the Popular Science website published the results of another widely publicized investigation — during a month-long trip across the United States, 17 additional IMSI catchers were detected.

Also, consider that in 2014 alone more than 300,000 secure phones were sold worldwide—devices meant to serve the opposite purpose of IMSI catchers. That number gives you a sense of how common IMSI catchers are, since it’s reasonable to assume a significant share of those buyers also use IMSI catchers. So your chances of encountering one are quite real.

So how viable is IMSI interception? Are there more effective alternatives?

Since you asked… There’s also Wi‑Fi radio imaging (RF sensing), which blends old‑school analog with modern digital power. It operates at a lower level, making it more flexible. In fact, it can track people even if they aren’t carrying any devices. Take, for example, WiSee, which recognizes human gestures; WiVe, which detects moving objects through walls; WiTrack, which follows a person’s 3D motion; and finally WiHear, which can read lips. But since these are fundamentally different technologies, we’ll dive into them another time.