There are plenty of reasons to export everything. For example, you might be migrating to another service and want to move your data there; you’ll probably need to convert it, but sometimes the hassle is worth it. Or maybe you want to build an analytics setup in the spirit of lifelogging and the quantified self, and the data you’ve accumulated in Google will help with that. Or the country you live in might suddenly wall off its internet with a “Great Firewall,” leaving Google out of reach. Unfortunately, that happens too.

Over the past twelve years, I’ve used a lot of Google products—testing many of them for reviews—and I’ve never turned off the tracking features. You might say that’s crazy, but first, Google has treated my data carefully and hasn’t given me a reason to panic, and second, I’m not advocating this approach. Think of it as me enduring this nightmare so you don’t have to! 🙂

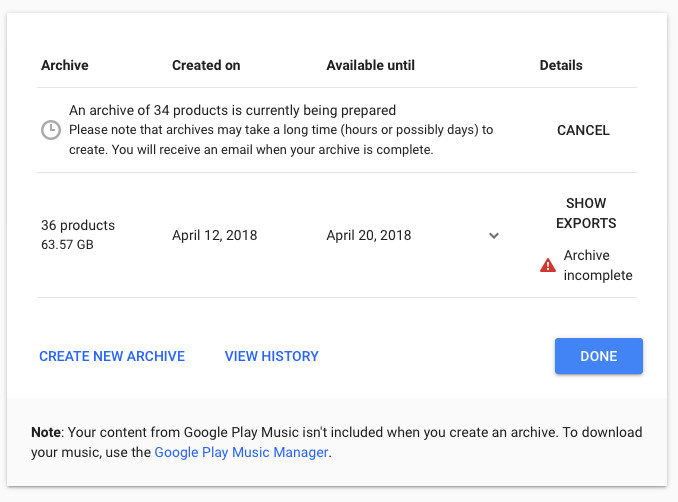

So, to get your archives, go to takeout.google.com, tick the boxes next to the services you want, and wait for a bit—long enough to notice. When I requested a full export, the link arrived a day later—more than 24 hours. The automated Google email said the data spanned 36 products, totaled 63.6 GB, and was split into three archives. Most of the data was in the first two; the third was just a zipped index page listing everything that was included.

If you don’t want to download that much data, request partial archives that exclude some services. For example, if you disable Photos, YouTube, and Gmail—and Drive as well if you keep anything there beyond test documents—you might end up with only a few hundred megabytes. Also, the smaller the archive, the sooner you’ll get the download link.

Search history

Let’s start with one of the most interesting bits—the search history. It’s stored in the Searches folder and split into three-month chunks, for example 2006-01-01 . If you open one of these files, you’ll see that each entry only has two fields: a Unix timestamp and the query string.

To convert timestamps, you can use an online converter. If you need to do it in bulk, it’s a one-liner in Python (replace the word “time” with your value):

datetime.datetime.fromtimestamp(int("time")).strftime('%d-%m%-%Y %H:%M:%S')I’ll leave the in‑depth analysis to you. For fun, let’s try searching for occurrences of specific strings with grep. Since the data is stored in JSON, we’ll first need to convert it into lines—I used the gron utility for that, which I recently wrote about in the WWW column.

If you have gron installed, you can do something like this:

$ for F in *; do cat "${F}" | gron | grep "xakep"; done

And you’ll see all your queries with the word “xakep” for all time. What other keywords can you try? For example, the word “download.” 🙂 Or here’s a neat idea: if you search for the “@” symbol, you’ll find all the email addresses and Twitter accounts you looked up on Google.

Note that image and video search aren’t available here, but we’ll find them in the My Activity section.

Chats

You might already have a folder tucked away with old ICQ logs and want to merge into it everything you ever wrote via Google Talk and Hangouts. That’s entirely doable, but unfortunately, the chats in the format they come from Google Takeout are almost unreadable (unlike ICQ logs).

All text is exported as a single JSON file plus a pile of attached images — all of it sits in the Hangouts folder. The images are no problem, but the JSON includes roughly a couple dozen lines of metadata for every message. The biggest headache, though, is that it uses the sender’s user ID instead of their name.

Probably the simplest thing we can do is strip away all the fluff and keep only the text. At least then we can see some conversations, even if they’re anonymized.

$ gron Hangouts.json | grep '.text'

At least this way there’s a chance to catch something.

Google+

What’s actually worth backing up is your Google+ posts—the service is quickly becoming a relic of the past. That is, if you ever used it in the first place.

The data is divided into three folders: Google+ Stream, Circles, and Pages. Let’s go through them one by one.

Circles are people’s contacts organized into Google+ “circles.” The format is vCard (VCF) with whatever information users provided about themselves. If you want, you can import them into any address book in one go.

The Pages folder will be there if you had any public pages. There’s nothing particularly useful in it—basically just the profile picture and the cover image.

Another part of the Google+ data is the Profile folder. It contains a JSON file with a copy of everything you entered about yourself on that social network. The most interesting bits are in the urls structure (links to your other social profiles) and organizations (workplaces with dates). A funny detail: even though my profile doesn’t list my age, there’s an "ageRange": { field here, which Google seems to have inferred on its own.

The most important stuff is in the Google+ Stream folder. There you’ll find all your posts with comments—and even individual comments—dumped as separate HTML files. You can browse them for nostalgia, or use a few lines of Python with BeautifulSoup to extract, say, just the post texts. You’ll need to select elements with the classes entry-title and entry-content.

Unfortunately, images in posts aren’t backed up automatically—they remain just links to Google’s servers, which won’t serve them without authentication. Bit of a miss!

Maps

Another major and important category of personal data. Let’s start with something simple—the MyMaps folder. These are routes you created in Google Maps, with one KMZ file per route.

KMZ is a Google Earth format that’s also supported by other mapping applications. Under the hood, it’s just a ZIP archive containing a KML file, which is valid XML. If that doesn’t fit your needs for any reason, you can use GeoConverter to convert it—e.g., to GeoJSON, which is a bit easier to work with.

The folder Maps (your places) contains a single file — Saved . It holds all your Google Maps bookmarks in yet another convoluted structure. Each bookmark is an element of the features array and includes a title, date added, date modified, and a link to Google Maps. The geocoordinates, however, can appear in different formats: either as a geometry object with a coordinates array, or as a Location object with Latitude and Longitude fields — though, just to keep things interesting, the same thing might be labeled Geo , for example. Accounting for all these quirks isn’t too hard if you want to, but it could certainly be simpler.

Finally, the most interesting folder is Location History—a file containing your complete location trail captured while your phone was in your pocket. My data comes to 7.5 MB.

The file format is very simple, especially compared to other archives. It’s essentially a large array of records containing: Unix timestamp, latitude, longitude, and positional accuracy. Sometimes additional fields are present (presumably when they could be determined): heading in degrees, altitude in meters, and altitude accuracy.

What else can you do with this file besides saving it for posterity? For example, you can practice analyzing it with Python or with R. There’s also dedicated software for exploring this kind of data — Location History Visualizer Pro (costs $70), as well as hobbyist services like They Know Where You’ve Been (if you’re really not worried about sharing this data with random people).

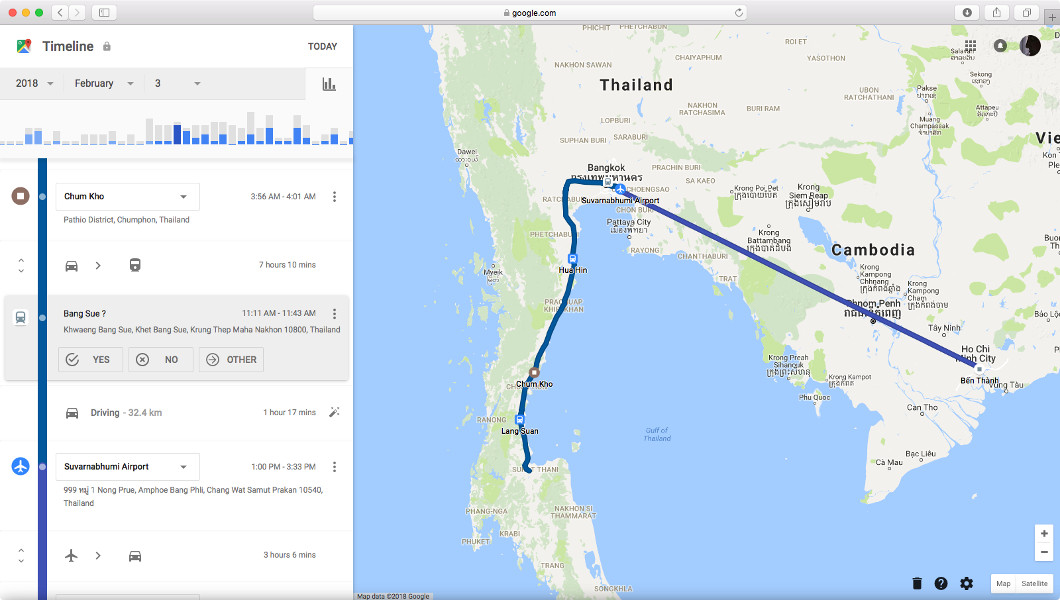

However, Google’s service is still unmatched here. Google Maps includes a Timeline tool where you can browse your collected data by day, and beyond the raw data you get via Takeout, it adds useful analytics. For example, Google infers the names of places and businesses you’ve visited and does an excellent job distinguishing modes of transport—easily telling whether you were on a motorcycle, in a car, or on a bicycle.

Chrome

This is a particularly interesting folder that contains the cloud-related part of Google Chrome (or maybe not all of it—you can never be sure!). Here’s what’s inside.

- Bookmarks.html — the bookmarks exported as an HTML list. Parsing is trivial: just grab URLs from a href and split into sections by h3 headings. Many bookmarks include an added-at Unix timestamp.

- Dictionary.csv — presumably custom spell-check exceptions, which I don’t have.

- Extensions.json — data about installed extensions.

- SearchEngines.json — data on additional search engines. If you ever need URL templates/rules for building search queries for different engines, this file is useful; otherwise, probably not.

- SyncSettings.json — Chrome sync settings.

- Autofill.json — in theory this should contain autofill form data, but mine is just an empty array. Seems easier to pull this straight from Chrome if needed.

- BrowserHistory.json — I expected a goldmine of personal data—the full list of every site I’ve ever opened in Chrome. Instead, disappointment: the file lists only fourteen links that I happened to open in mobile Chrome when I installed it to take a look. On desktop I have a hefty site list and “Sync everything” enabled. Google Takeout glitch?

If you have better luck with the last item, you’ll be able to easily analyze your browsing history. Google records the transition type (via link — LINK, or direct — TYPED), the page title, the URL, a client ID (useful for distinguishing your desktop from your phone or tablet), and a Unix timestamp.

My Activity

This is arguably one of the most interesting folders—maybe even more interesting than your search history. Its contents answer the question of how exactly Google tracks users. By browsing through the folders, you can see for yourself what it records every:

- visiting a site affiliated with Google AdWords

- a book opened in Google Books

- a site you visited in Chrome

- an API you accessed (Developers folder)

- a quote opened in Google Finance

- a Google Goggles query (object search in a photo)

- viewing a page in the Google Play Store

- accessing Help (Help folder)

- a Google Image Search query and clicking through to a result

- viewing a place in Google Maps

- a search in Google News and reading the article on the source site

- a web search and clicking a result (Search folder)

- searching for a product or making a purchase (Shopping folder)

- viewing trips in Google Trips

- a video search and clicking through from the results (Video Search)

- voice search (Voice and Audio folder)

- a search query and watching videos on YouTube

I should note that my Chrome browsing history was just as half-empty as Chrome’s own folder, and the Shopping section is basically useless: over twelve years, Google barely registered a couple of real purchases. Even so, the data trove is pretty substantial. I’m especially pleased by the MP3 files in the Voice and Audio folder: you can listen to your own voice saying things like “OK, Google…”.

www

You can view and filter the same data on myactivity.google.com. You can also delete individual entries there and disable tracking for specific activities.

The format it all gets exported in leaves a lot to be desired. It’s HTML again, with less-than-readable markup and a 150‑kilobyte chunk of Material Design in every file. I threw together a quick Python script you can drop into any folder and run.

import retext = open('MyActivity.html', 'r').read()result = re.findall(r'body-1">(.+?)</div>', text)for r in result: for s in r.split('>'): print s.split('<')[0]You’ll get cleaned-up text as output that you can, for example, pipe into grep or keep structuring further. In short, there’s plenty of room to explore.

Other Products

We won’t analyze the data for all four dozen products in detail, but we’ll briefly go over the remaining services.

+1 — an HTML file listing the pages you’ve +1’d on Google+. In my case, it was four random pages.

Bookmarks — same idea, but for bookmarks. For reasons unknown, mine contained only Google Maps bookmarks — the stars you use to mark places on the map. The format is HTML with links to Google Maps. If you open it in an editor, you can also extract the time each was added and, in some cases, the geo-coordinates. All of this is fully duplicated in the Maps (your places) folder, and in a more convenient form.

Calendar — user calendars exported from Google Calendar in the iCalendar (.ics) format, which is supported by many calendar apps (including Outlook, Thunderbird, and Apple Calendar), so you can import them directly.

Photos. If you use Photos a lot, this folder will contain a long list of subfolders—one for each day that has at least one shot. The good news is that all photos are stored and exported in their original format, even huge RAW files. And, importantly, this holds true even if you’re on the free Photos tier, which supposedly imposes a quality cap. Each photo comes with a JSON file containing its metadata.

YouTube. First and foremost, you’ll find every video you’ve ever uploaded to YouTube here. As with photos, they’re provided in their original formats. And of course, each one comes with a JSON file containing metadata. You’ll also get playlists, subscriptions in OPML format, your watch and search history in HTML (similar to what we saw in My Activity), and even your comments—also in HTML.

Classic Sites — websites built with the not‑so‑popular Google Sites service (something between narod.ru and Wikia). I made a couple of test sites ages ago and then didn’t touch the service for years. They’re still around, though, and get exported via Takeout. Cross-links work locally, but images stay on Google’s servers. And you probably don’t want to peek inside the pages—instead of source code you’ll see piles of minified “optimized” JS, in the worst Google tradition.

Drive — all documents from Google Drive. Text is exported as DOCX, spreadsheets as XLSX, and comments as HTML, using the document’s title as the filename. It’s convenient that file names mirror the titles, and the folder structure is preserved as well.

Google Pay. Information from this service is split into two folders: Google Pay Send — a list of transactions made via Google Pay (in my case, an empty CSV file), and Google Pay rewards, gift cards, offers (in my case, an empty PDF).

Mail is a complete archive of your Gmail messages. The folder contains a single file — All . The name says it all: it’s every message, including spam and trash. The format is mbox—basically one huge text file with all messages and their headers concatenated. Most mail clients can import it, but it’s usually easier to connect the client directly to Gmail and fetch only the folders you need over IMAP. Takeout is mainly useful if you want to grab absolutely everything in one shot as an archive and keep it for later.

Google My Business — in my case there’s basically nothing to see here, just a tiny JSON with three fields: account ID, first and last name, and a “personal” flag.

Contacts — the Gmail address book. Contacts are split into folders by group, plus there’s an All Contacts folder that aggregates (and duplicates) the contents of the others. Inside each folder you’ll find a vCard file and profile photos. A funny quirk: the images appear in full, exactly as they were uploaded to Google. So if someone cropped their face into a circle and assumed the rest would never be visible, they’re mistaken.

G Suite Marketplace — plugins for Google apps that you’d publish to the official store. I didn’t publish any, so I only have one file — a README.

Tasks — for about a decade now, there’s been a Google service for managing to‑do lists, tucked away in places like Gmail and Calendar. Here you can also find its export as a fairly convoluted JSON structure.

Google Play Books — When I saw subfolders named after book titles, I got excited for a moment: did I just find a way to grab copies of books purchased in Play Books? Ha—of course not. Instead, each subfolder contains an HTML file with the book’s title, author name, the last-opened time, an internal Play Books ID, and a link. Not hugely useful, but if you have a lot of books you can at least extract a list by pulling titles and author names from elements with the classes header and author.

There are a few products left that I have nothing on in my archive because I never used them: Blogger, Classroom, Fit, Play Music, Groups, Handsfree, Hangouts on Air, Keep, Search Contributions, and Voice. Arguably the biggest gap is Keep, but you can find a ready-made parser for its data in this repository.

Key takeaways

In other words, aside from email, photos, and documents, the key archives are Searches, Location History, the BrowserHistory.json file from the Chrome folder, and My Activity.

Can we ultimately say that Google Takeout exports all your personal data? Unlikely. At a minimum, older, discontinued services are missing: there’s no Google Reader data and no Wave conversations. Knowing Google, I find it hard to believe all that data was deleted. More likely, it was moved to cold storage.

If you look closely, you can find other gaps in the Takeout export as well. I’ve already mentioned the absence of data from desktop Chrome, but there are subtler issues too. For example, the page for viewing your activity online includes not only your search queries but also the location you performed them from. There’s nothing like that in the My Activity folder yet.

Despite these shortcomings, Google’s team deserves credit: it’s rare to see a service’s developers put so much effort into improving data portability and making collection practices more transparent. As a result, Google Takeout is useful not only for grabbing your data and walking away, but also for all kinds of analysis.