Types of Cheats and Their Tactics

There are different types of cheats, which can be categorized into several groups.

- External – cheats that operate in a separate process. If we conceal our external cheat by loading it into the memory of another process, it transforms into a hidden external.

- Internal – cheats that integrate into the game’s process using an injector. After being loaded into the game’s memory, the entry point of the cheat is triggered in a separate thread.

- Pixelscan – a type of cheat that utilizes the screen image and patterns of pixel placement to extract necessary information from the game.

- Network proxy – cheats that employ network proxies to intercept client-server traffic, allowing them to retrieve or modify necessary data.

There are three primary tactics for modifying game behavior.

- Game Memory Modification: Utilizing the operating system’s API to locate and modify memory sections that contain desired information, such as health or ammunition.

- Player Action Simulation: The application replicates player actions by clicking the mouse in predetermined locations.

- Game Traffic Interception: The cheat intervenes between the game and the server to intercept data, gathering or altering information to deceive either the client or the server.

Most modern games are developed for Windows, so our examples will focus on this platform.

Creating a Game in C

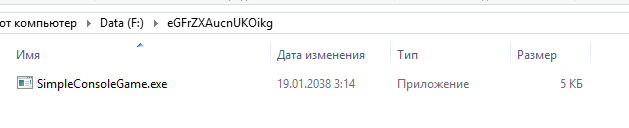

It’s best to discuss cheats in practice. We’ll create our own small game to practice on. I’ll be developing the game in C#, but I will try to align the data structure as closely as possible to a C++ game. In my experience, it’s quite easy to cheat in games written in C#.

The game’s premise is simple: you press Enter and you lose. Not exactly fair rules, right? Let’s try to change them.

Let’s Dive into Reverse Engineering

We have the game’s file, but instead of examining the source code, we will analyze the application’s memory and behavior.

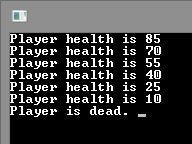

Each time Enter is pressed, the player’s life decreases by 15. The initial amount of life is 100.

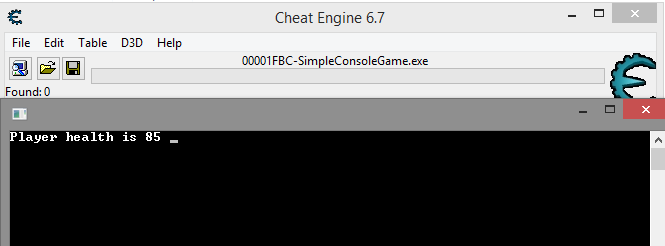

We will study memory using Cheat Engine. This application is used to search for variables within an application’s memory and also serves as a good debugger. Let’s restart the game and connect Cheat Engine to it.

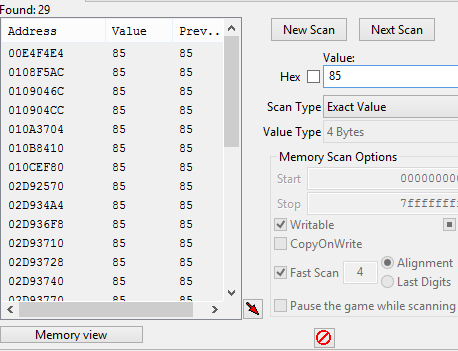

The first step is to generate a list of all occurrences of the value 85 in memory.

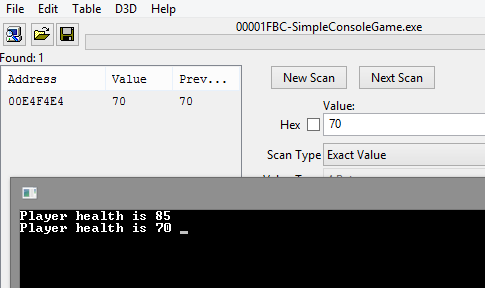

Press Enter, and the life points will be set to 70. We will filter out all other values.

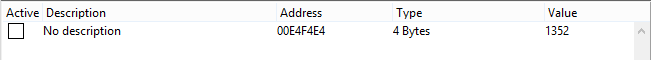

That’s the value we need! Let’s modify it and press Enter to verify the result.

The issue is that after restarting the game, the value will be located at a different address. It makes no sense to filter it out every time. You need to use AOB (Array Of Bytes) scanning.

Each time the application is opened, due to Address Space Layout Randomization (ASLR), the structure that describes the player will be located at a new address. To find it, you must first identify a signature. A signature is a set of unchanging bytes within the structure that can be used to search through the application’s memory.

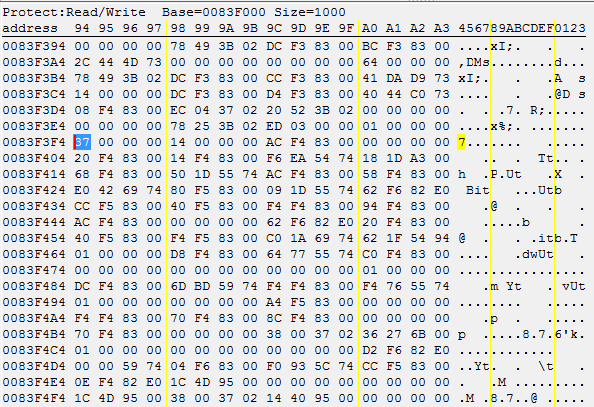

After pressing Enter a few times, the number of lives changed to 55. Let’s find the relevant value in memory again and open the region where it’s located.

The highlighted byte marks the beginning of our int32 number. 37 represents the number 55 in decimal form.

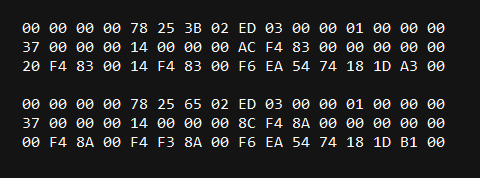

I’ll copy a small region of memory and paste it into a text editor for further analysis. Now, let’s restart the application and find the same value in memory again. We’ll copy the same memory region and paste it into the text editor once more. The goal is to start comparing these to identify the bytes near this signature that remain constant.

Let’s check the bytes before the structure.

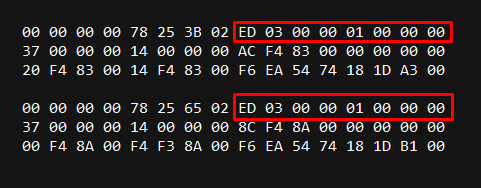

As you can see, the highlighted bytes have not changed, which means you can try using them as a signature. The smaller the signature, the faster the scanning process. A signature like 01 is likely to appear too frequently in memory. It’s better to use 03 . To begin, let’s find it in memory.

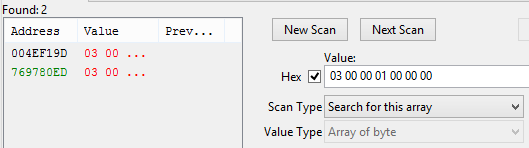

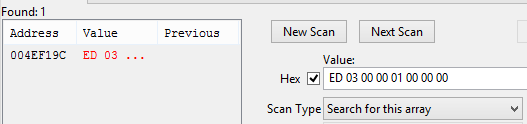

The signature has been found, but it repeats. A more unique sequence is needed. Let’s try ED .

To confirm uniqueness, we will achieve the following result:

We need to determine the offset from the signature to obtain its starting address, rather than the address for lives. For now, let’s save the found signature and set it aside for a bit. Don’t worry, we’ll come back to it later.

The Lifecycle of External Cheats

External cheats employ the OpenProcess function to obtain a handle to the target process, allowing them to make necessary code changes (patching) or to read and modify variables within the game’s memory. The functions ReadProcessMemory and WriteProcessMemory are used for memory modification.

Since dynamic data allocation in memory makes it difficult to record the needed addresses and access them consistently, you can use the AOB (Array of Bytes) scanning technique. The lifecycle of an external cheat looks like this:

- Locate the process ID.

- Obtain a handle to this process with the necessary permissions.

- Find memory addresses.

- Apply patches if needed.

- Render the GUI, if there is one.

- Read or modify memory as needed.

Creating an External Cheat for Your Game

C# uses the P/Invoke technology to call WinAPI functions. To start working with these functions, you have to declare them in your code. I will be using ready-made declarations from pinvoke.net. The first function to be used is OpenProcess.

[Flags]

public enum ProcessAccessFlags : uint

{

All = 0x001F0FFF,

Terminate = 0x00000001,

CreateThread = 0x00000002,

VirtualMemoryOperation = 0x00000008,

VirtualMemoryRead = 0x00000010,

VirtualMemoryWrite = 0x00000020,

DuplicateHandle = 0x00000040,

CreateProcess = 0x000000080,

SetQuota = 0x00000100,

SetInformation = 0x00000200,

QueryInformation = 0x00000400,

QueryLimitedInformation = 0x00001000,

Synchronize = 0x00100000

}

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", SetLastError = true)]

public static extern IntPtr OpenProcess(

ProcessAccessFlags processAccess,

bool bInheritHandle,

int processId);

The next function is ReadProcessMemory.

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", SetLastError = true)]

public static extern bool ReadProcessMemory(

IntPtr hProcess,

IntPtr lpBaseAddress,

[Out] byte[] lpBuffer,

int dwSize,

out IntPtr lpNumberOfBytesRead);

Now, let’s discuss the memory reading function WriteProcessMemory.

[DllImport("kernel32.dll", SetLastError = true)]

public static extern bool WriteProcessMemory(

IntPtr hProcess,

IntPtr lpBaseAddress,

byte[] lpBuffer,

int nSize,

out IntPtr lpNumberOfBytesWritten);

We are faced with a problem: to find a pattern, it’s necessary to gather all the memory regions of a process. For this, we need a function and a structure. The function is VirtualQueryEx:

[DllImport("kernel32.dll")]

static extern int VirtualQueryEx(IntPtr hProcess, IntPtr lpAddress, out MEMORY_BASIC_INFORMATION lpBuffer, uint dwLength);

Structure MEMORY_BASIC_INFORMATION:

[StructLayout(LayoutKind.Sequential)]

public struct MEMORY_BASIC_INFORMATION

{

public IntPtr BaseAddress;

public IntPtr AllocationBase;

public uint AllocationProtect;

public IntPtr RegionSize;

public uint State;

public uint Protect;

public uint Type;

}

Now it’s time to start coding the actual cheat. First, let’s locate the game.

private static int WaitForGame()

{

while (true)

{

var prcs = Process.GetProcessesByName("SimpleConsoleGame");

if (prcs.Length != 0)

{

return prcs.First().Id;

}

Thread.Sleep(150);

}

}

Next, we’ll open the file descriptor for our game.

private static IntPtr GetGameHandle(int id)

{

return WinAPI.OpenProcess(WinAPI.ProcessAccessFlags.All, false, id);

}

Let’s integrate all of this into the initial code.

Console.Title = "External Cheat Example";

Console.ForegroundColor = ConsoleColor.White;

Console.WriteLine("Waiting for game process..");

var processId = WaitForGame();

Console.WriteLine($"Game process found. ID: {processId}");

var handle = GetGameHandle(processId);

if (handle == IntPtr.Zero)

{

CriticalError("Error. Process handle acquirement failed.\n" +

"Insufficient rights?");

}

Console.WriteLine($"Handle was acquired: 0x{handle.ToInt32():X}");

Console.ReadKey(true);

We’ll find the process ID, then obtain its handle, and if necessary, display an error message. The implementation of CriticalError( isn’t that important.

After this, we can move on to pattern searching in memory. We’ll create a general class containing all the functions needed for working with memory, which we’ll call MemoryManager. Then, we’ll create a class called MemoryRegion to describe a memory region. The MEMORY_BASIC_INFORMATION structure includes a lot of unnecessary data that should not be passed on, so I’ve extracted these into a separate class.

public class MemoryRegion

{

public IntPtr BaseAddress { get; set; }

public IntPtr RegionSize { get; set; }

public uint Protect { get; set; }

}

This is all we need: the starting address of the region, its size, and its protection settings. Now, how do we obtain all the memory regions? Let’s find out.

- Retrieve information about the memory region at address zero.

- Check the status and protection of the region. If everything is fine, add it to the list.

- Retrieve information about the next region.

- Check and add it to the list.

- Repeat the cycle.

public List<MemoryRegion> QueryMemoryRegions() {

long curr = 0;

var regions = new List<MemoryRegion>();

while (true) {

try {

var memDump = WinAPI.VirtualQueryEx(_processHandle, (IntPtr) curr, out var memInfo, 28);

if (memDump == 0) break;

if ((memInfo.State & 0x1000) != 0 && (memInfo.Protect & 0x100) == 0)

{

regions.Add(new MemoryRegion

{

BaseAddress = memInfo.BaseAddress,

RegionSize = memInfo.RegionSize,

Protect = memInfo.Protect

});

}

curr = (long) memInfo.BaseAddress + (long) memInfo.RegionSize;

} catch {

break;

}

}

return regions;

}

Once we have the regions, we will scan them for the pattern we need. The pattern consists of two types of segments: known and unknown (changing byte). For example, 00 . We’ll create an interface to describe these segments.

interface IMemoryPatternPart

{

bool Matches(byte b);

}

Now let’s describe the section that has a known byte.

public class MatchMemoryPatternPart : IMemoryPatternPart

{

public byte ValidByte { get; }

public MatchMemoryPatternPart(byte valid)

{

ValidByte = valid;

}

public bool Matches(byte b) => ValidByte == b;

}

Let’s do the same thing with the second type.

public class AnyMemoryPatternPart : IMemoryPatternPart

{

public bool Matches(byte b) => true;

}

Now let’s parse the pattern from the string.

private void Parse(string pattern)

{

var parts = pattern.Split(' ');

_patternParts.Clear();

foreach (var part in parts)

{

if (part.Length != 2)

{

throw new Exception("Invalid pattern.");

}

if (part.Equals("??"))

{

_patternParts.Add(new AnyMemoryPatternPart());

continue;

}

if (!byte.TryParse(part, NumberStyles.HexNumber, null, out var result))

{

throw new Exception("Invalid pattern.");

}

_patternParts.Add(new MatchMemoryPatternPart(result));

}

}

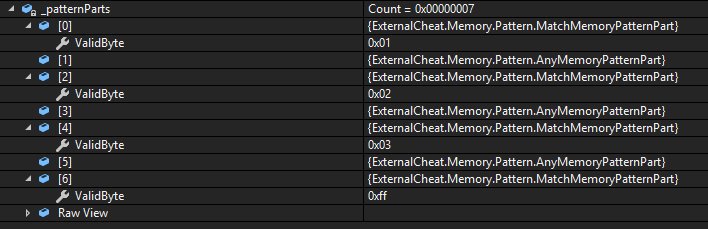

As done previously, check the type of pattern part, parse it if necessary, and add it to the list. It’s important to verify the functionality of this method.

var p = new MemoryPattern("01 ?? 02 ?? 03 ?? FF");

Now we need to teach our MemoryManager to read memory.

public byte[] ReadMemory(IntPtr addr, int size)

{

var buff = new byte[size];

return WinAPI.ReadProcessMemory(_processHandle, addr, buff, size, out _) ? buff : null;

}

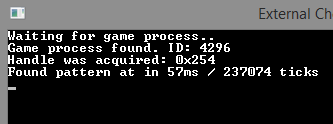

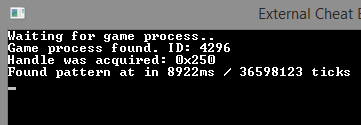

Initially, I wrote an elegant function using Linq to scan memory. However, its execution was quite slow. Then, I rewrote the method without using that technology, and everything worked much faster. The result of the optimized function:

The result of the original function:

Now, let me share some wisdom gained at this stage: don’t be afraid to optimize your code. Libraries don’t always offer the fastest solutions. Here’s the original function:

public IntPtr ScanForPatternInRegion(MemoryRegion region, MemoryPattern pattern)

{

var endAddr = (int) region.RegionSize - pattern.Size;

var wholeMemory = ReadMemory(region.BaseAddress, (int) region.RegionSize);

for (var addr = 0; addr < endAddr; addr++)

{

var b = wholeMemory.Skip(addr).Take(pattern.Size).ToArray();

if (!pattern.PatternParts.First().Matches(b.First()))

{

continue;

}

if (!pattern.PatternParts.Last().Matches(b.Last()))

{

continue;

}

var found = true;

for (var i = 1; i < pattern.Size - 1; i++)

{

if (!pattern.PatternParts[i].Matches(b[i]))

{

found = false;

break;

}

}

if (!found)

{

continue;

}

return region.BaseAddress + addr;

}

return IntPtr.Zero;

}

Revised function: just use Array..

public IntPtr ScanForPatternInRegion(MemoryRegion region, MemoryPattern pattern)

{

var endAddr = (int) region.RegionSize - pattern.Size;

var wholeMemory = ReadMemory(region.BaseAddress, (int) region.RegionSize);

for (var addr = 0; addr < endAddr; addr++)

{

var buff = new byte[pattern.Size];

Array.Copy(wholeMemory, addr, buff, 0, buff.Length);

var found = true;

for (var i = 0; i < pattern.Size; i++)

{

if (!pattern.PatternParts[i].Matches(buff[i]))

{

found = false;

break;

}

}

if (!found)

{

continue;

}

return region.BaseAddress + addr;

}

return IntPtr.Zero;

}

This function searches for a pattern within a memory region. The following function utilizes it to scan the entire process’s memory.

public IntPtr PatternScan(MemoryPattern pattern)

{

var regions = QueryMemoryRegions();

foreach (var memoryRegion in regions)

{

var addr = ScanForPatternInRegion(memoryRegion, pattern);

if (addr == IntPtr.Zero)

{

continue;

}

return addr;

}

return IntPtr.Zero;

}

Let’s add two functions for reading and writing a 32-bit number from memory.

public int ReadInt32(IntPtr addr)

{

return BitConverter.ToInt32(ReadMemory(addr, 4), 0);

}

public void WriteInt32(IntPtr addr, int value)

{

var b = BitConverter.GetBytes(value);

WinAPI.WriteProcessMemory(_processHandle, addr, b, b.Length, out _);

}

Everything is now set up for pattern detection and writing the main cheat code.

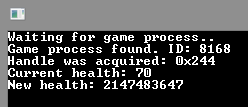

var playerBase = memory.PatternScan(new MemoryPattern("ED 03 00 00 01 00 00 00"));

Locate the pattern in memory, then find the player’s lives address.

var playerHealth = playerBase + 24;

Reading the number of lives:

Console.WriteLine($"Current health: {memory.ReadInt32(playerHealth)}");

Why not give the player almost infinite lives?

memory.WriteInt32(playerHealth, int.MaxValue);

And once again, we’re counting player lives for demonstration purposes.

Console.WriteLine($"New health: {memory.ReadInt32(playerHealth)}");

Checking

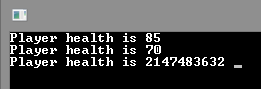

Let’s start our cheat, and then launch the game.

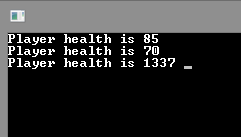

Let’s try pressing Enter in the “game.”

The cheat is working!

Creating Your First Code Injector

There are many ways to make a process load our code. You can use DLL Hijacking, or SetWindowsHookEx. However, we’ll start with the simplest and most well-known function — LoadLibrary. LoadLibrary makes the target process load the library by itself.

We will need a handle with the necessary permissions. Let’s start preparing for the injection. First, we’ll ask the user for the name of the library.

Console.Write("> Enter DLL name: ");

var dllName = Console.ReadLine();

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(dllName) || !File.Exists(dllName))

{

Console.WriteLine("DLL name is invalid!");

Console.ReadLine();

return;

}

var fullPath = Path.GetFullPath(dllName);

Next, we will ask the user for the process name and find its ID.

var fullPath = Path.GetFullPath(dllName);

var fullPathBytes = Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes(fullPath);

Console.Write("> Enter process name: ");

var processName = Console.ReadLine();

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(dllName))

{

Console.WriteLine("Process name is invalid!");

Console.ReadLine();

return;

}

var prcs = Process.GetProcessesByName(processName);

if (prcs.Length == 0)

{

Console.WriteLine("Process wasn't found.");

Console.ReadLine();

return;

}

var prcId = prcs.First().Id;

This code will have issues with processes that have the same name.

Now let’s move on to the first injection method.

Implementing LoadLibrary Injection

Let’s start by examining how this type of injector works.

- First, it reads the full path to the library from the disk.

- It converts the path into a string.

- Then we retrieve the address of

LoadLibraryA(usingLPCSTR) GetProcAddress(.HMODULE, LPCSTR) - Allocates memory for the string within the application and writes the string there.

- Afterwards, it creates a thread at the

LoadLibraryAaddress, passing the path as an argument.

To proceed, you need to specify the imports: OpenProcess, ReadProcessMemory, WriteProcessMemory, GetProcAddress, GetModuleHandle, CreateRemoteThread, and VirtualAllocEx.

www

Signatures can easily be found on pinvoke.net.

First, we need to open a handle with full access to the process.

var handle = WinAPI.OpenProcess(WinAPI.ProcessAccessFlags.All,

false,

processID);

if (handle == IntPtr.Zero)

{

Console.WriteLine("Can't open process.");

return;

}

Let’s convert our string into bytes.

var libraryPathBytes = Encoding.ASCII.GetBytes(libraryPath);

Next, you need to allocate memory for this string.

var memory = WinAPI.VirtualAllocEx(handle,

IntPtr.Zero,

256,

WinAPI.AllocationType.Commit | WinAPI.AllocationType.Reserve,

WinAPI.MemoryProtection.ExecuteReadWrite);

A process handle handle is passed to the function, with _MAX_PATH as the maximum path size in Windows, which is 256. We specify that the memory can be written, read, and executed. Then, we write a string into the process.

WinAPI.WriteProcessMemory(handle, memory, libraryPathBytes, libraryPathBytes.Length, out var bytesWritten);

Since we’ll be using the LoadLibraryA function to load the library, we need to obtain its address.

var funcAddr = WinAPI.GetProcAddress(WinAPI.GetModuleHandle("kernel32"), "LoadLibraryA");

Everything is ready to start the injection process. All that remains is to create a thread in the remote application:

var thread = WinAPI.CreateRemoteThread(handle, IntPtr.Zero, IntPtr.Zero, funcAddr, memory, 0, IntPtr.Zero);

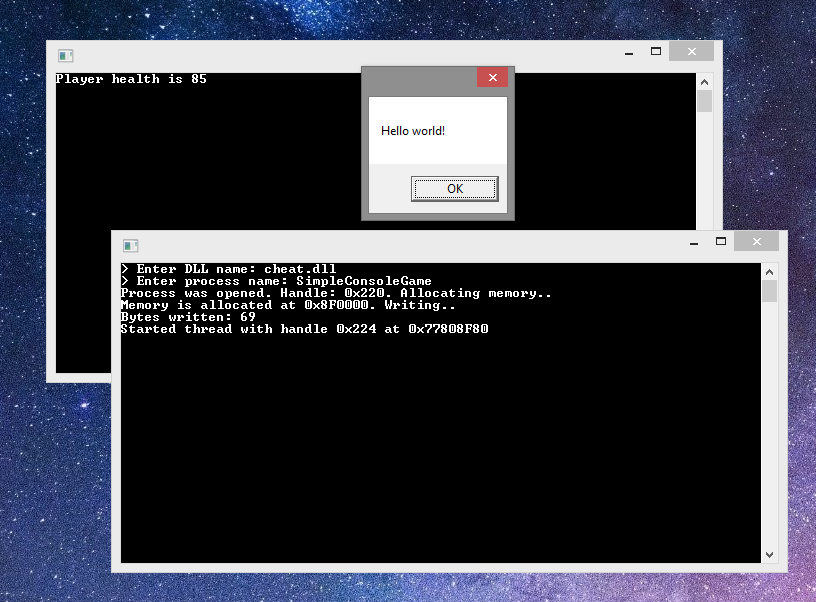

The injector is ready, but we will only test it after developing a simple library.

Building the Foundation for an Internal Cheat

Let’s switch to C++! We’ll start with the entry point and a simple message using the WinAPI. The entry point of a DLL should accept three parameters: HINSTANCE, DWORD, and LPVOID.

-

HINSTANCE— refers to a library instance. -

DWORD— indicates the reason for the entry point call (loading and unloading of the DLL). -

LPVOID— a reserved value.

Here’s what an empty library entry point looks like:

#include <Windows.h>

BOOL WINAPI DllMain(

_In_ HINSTANCE hinstDLL,

_In_ DWORD fdwReason,

_In_ LPVOID lpvReserved

)

{

return 0;

}

Let’s start by examining why the entry point is being invoked.

if(fdwReason == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH) { }

The fdwReason argument will be DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH if the library has just been attached to the process, or DLL_PROCESS_DETACH if it is in the process of being unloaded. For testing purposes, let’s display a message:

if(fdwReason == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH)

{

MessageBox(nullptr, "Hello world!", "", 0);

}

Now we can test the injector and this library. Run the injector and enter the names of the library and the process.

Now let’s write a simple class using the singleton pattern for cleaner code.

#pragma once

class internal_cheat

{

public:

static internal_cheat* get_instance();

void initialize();

void run();

private:

static internal_cheat* _instance;

bool was_initialized_ = false;

internal_cheat();

};

Now for the code itself: the default constructor and the singleton pattern.

internal_cheat::internal_cheat() = default;

internal_cheat* internal_cheat::get_instance()

{

if(_instance == nullptr)

{

_instance = new internal_cheat();

}

return _instance;

}

Here’s a simple entry point code.

#include <Windows.h>#include "InternalCheat.h"BOOL WINAPI DllMain( _In_ HINSTANCE hinstDLL, _In_ DWORD fdwReason, _In_ LPVOID lpvReserved){ if(fdwReason == DLL_PROCESS_ATTACH) { auto cheat = internal_cheat::get_instance(); cheat->initialize(); cheat->run(); } return 0;}I must say that the next part took the most time. One small mistake led to a huge waste of time. However, I’ve learned from it and will explain where such an error can occur and how to detect it.

We need to identify a pattern within the game’s memory. To achieve this, we will first iterate through all the memory regions of the application and then scan each of them. Below is an implementation for retrieving the list of memory regions, but it only applies to our own process. I have previously explained how it functions.

DWORD internal_cheat::find_pattern(std::string pattern){ auto mbi = MEMORY_BASIC_INFORMATION(); DWORD curr_addr = 0; while(true) { if(VirtualQuery(reinterpret_cast<const void*>(curr_addr), &mbi, sizeof mbi) == 0) { break; } if((mbi.State == MEM_COMMIT || mbi.State == MEM_RESERVE) && (mbi.Protect == PAGE_READONLY || mbi.Protect == PAGE_READWRITE || mbi.Protect == PAGE_EXECUTE_READ || mbi.Protect == PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)) { auto result = find_pattern_in_range(pattern, reinterpret_cast<DWORD>(mbi.BaseAddress), reinterpret_cast<DWORD>(mbi.BaseAddress) + mbi.RegionSize); if(result != NULL) { return result; } } curr_addr += mbi.RegionSize; } return NULL;}For each identified region, this code calls the function find_pattern_in_range, which searches for a pattern within that region.

DWORD internal_cheat::find_pattern_in_range(std::string pattern, const DWORD range_start, const DWORD range_end){ auto strstream = istringstream(pattern); vector<int> values; string s;Initially, the function parses the pattern.

while (getline(strstream, s, ' ')) { if (s.find("??") != std::string::npos) { values.push_back(-1); continue; } auto parsed = stoi(s, 0, 16); values.push_back(parsed); }Then the scanning process begins.

for(auto p_cur = range_start; p_cur < range_end; p_cur++ ) { auto localAddr = p_cur; auto found = true; for (auto value : values) { if(value == -1) { localAddr += 1; continue; } auto neededValue = static_cast<char>(value); auto pCurrentValue = reinterpret_cast<char*>(localAddr); auto currentValue = *pCurrentValue; if(neededValue != currentValue) { found = false; break; } localAddr += 1; } if(found) { return p_cur; } } return NULL;}I used a vector of int to store pattern data, where -1 indicates that any byte can be present. I did this to simplify and speed up the pattern search without having to convert the same code from an external cheat repeatedly.

Now a few words about the error I mentioned earlier. I kept rewriting the pattern search function until I decided to take a look at the memory region search function. The issue was that I was comparing the memory protection completely incorrectly. Here’s the initial version:

if((mbi.State == MEM_COMMIT || mbi.State == MEM_RESERVE) && (mbi.Protect == PAGE_EXECUTE_READ || mbi.Protect == PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)) { }The code was designed to accept only pages with readable/executable memory and readable/writable/executable memory. All other types of pages were ignored. The code was then modified to the following:

if((mbi.State == MEM_COMMIT || mbi.State == MEM_RESERVE) && (mbi.Protect == PAGE_READONLY || mbi.Protect == PAGE_READWRITE || mbi.Protect == PAGE_EXECUTE_READ || mbi.Protect == PAGE_EXECUTE_READWRITE)) { }This function has started identifying all the necessary memory pages.

info

PAGE_READONLY может вызвать критическую ошибку во время записи данных, у нас всегда есть VirtualProtect.

I discovered this error when I started checking memory pages in the application using Process Hacker and Cheat Engine. My pattern was in one of the very first memory regions with execution protection, which is why it was never found.

Now, having identified the pattern, we can store it in our class field.

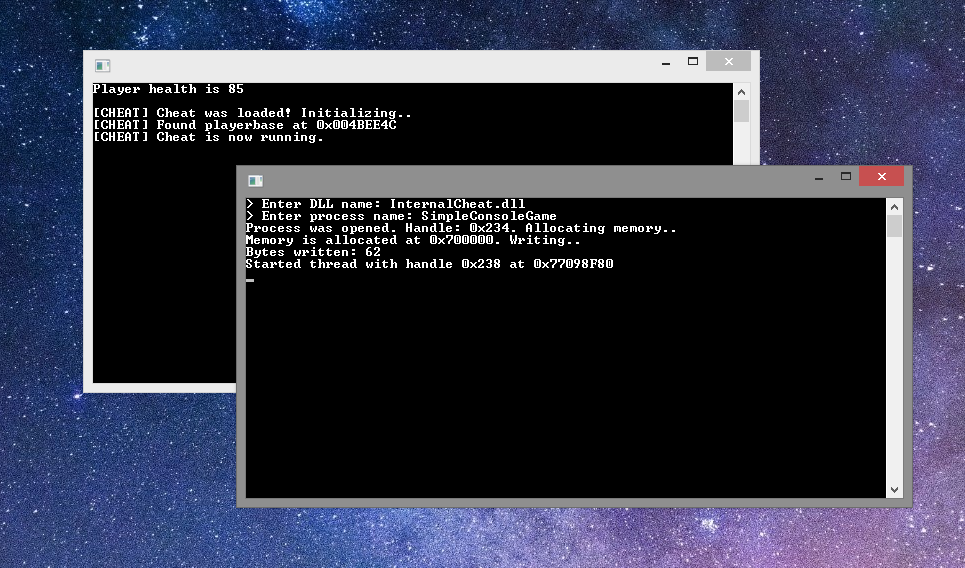

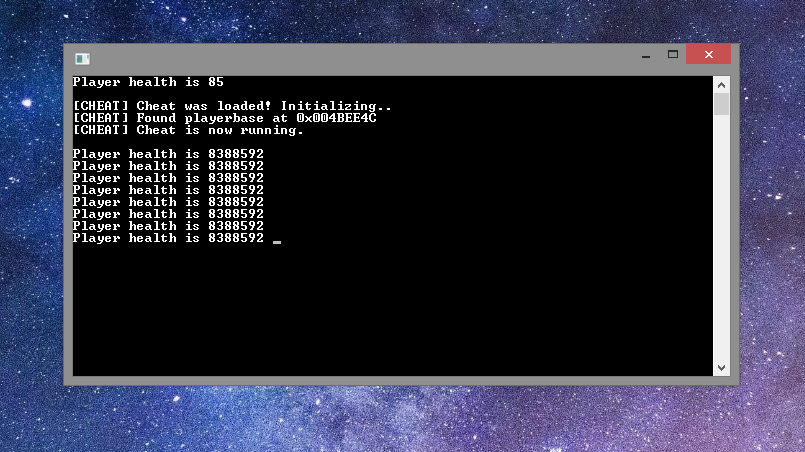

void internal_cheat::initialize(){ if(was_initialized_) { return; } printf("\n\n[CHEAT] Cheat was loaded! Initializing..\n"); was_initialized_ = true; player_base_ = reinterpret_cast<void*>(find_pattern("ED 03 00 00 01 00 00 00")); printf("[CHEAT] Found playerbase at 0x%p\n", player_base_);}After this, the function internal_cheat:: will be called, which is responsible for executing all the cheat features.

void internal_cheat::run(){ printf("[CHEAT] Cheat is now running.\n"); const auto player_health = reinterpret_cast<int*>(reinterpret_cast<DWORD>(player_base_) + 7); while(true) { *player_health = INT_MAX; Sleep(100); }}We simply retrieve the player’s life address from our pattern and set it to the maximum value (INT_MAX) every 100 milliseconds.

Testing Our Cheat

Launch the game and inject the library.

Let’s try pressing the Enter key a couple of times.

Our lives haven’t changed and everything is working perfectly!

Summary

Any element of a game that is processed on our computer can be modified or even removed. Unfortunately or fortunately, gaming companies don’t always prioritize anti-cheat measures, which opens the door for us, the cheaters.

www

- Cheat Source Code on GitHub