For this piece, I picked three quirks of recent Android releases that strike me as the most puzzling and obstructive. Each has its reasons for existing, and in most cases those reasons come down to a lack of expertise among software developers and users alike. So yes, this is a biased take (as a column should be), written by a power user for power users.

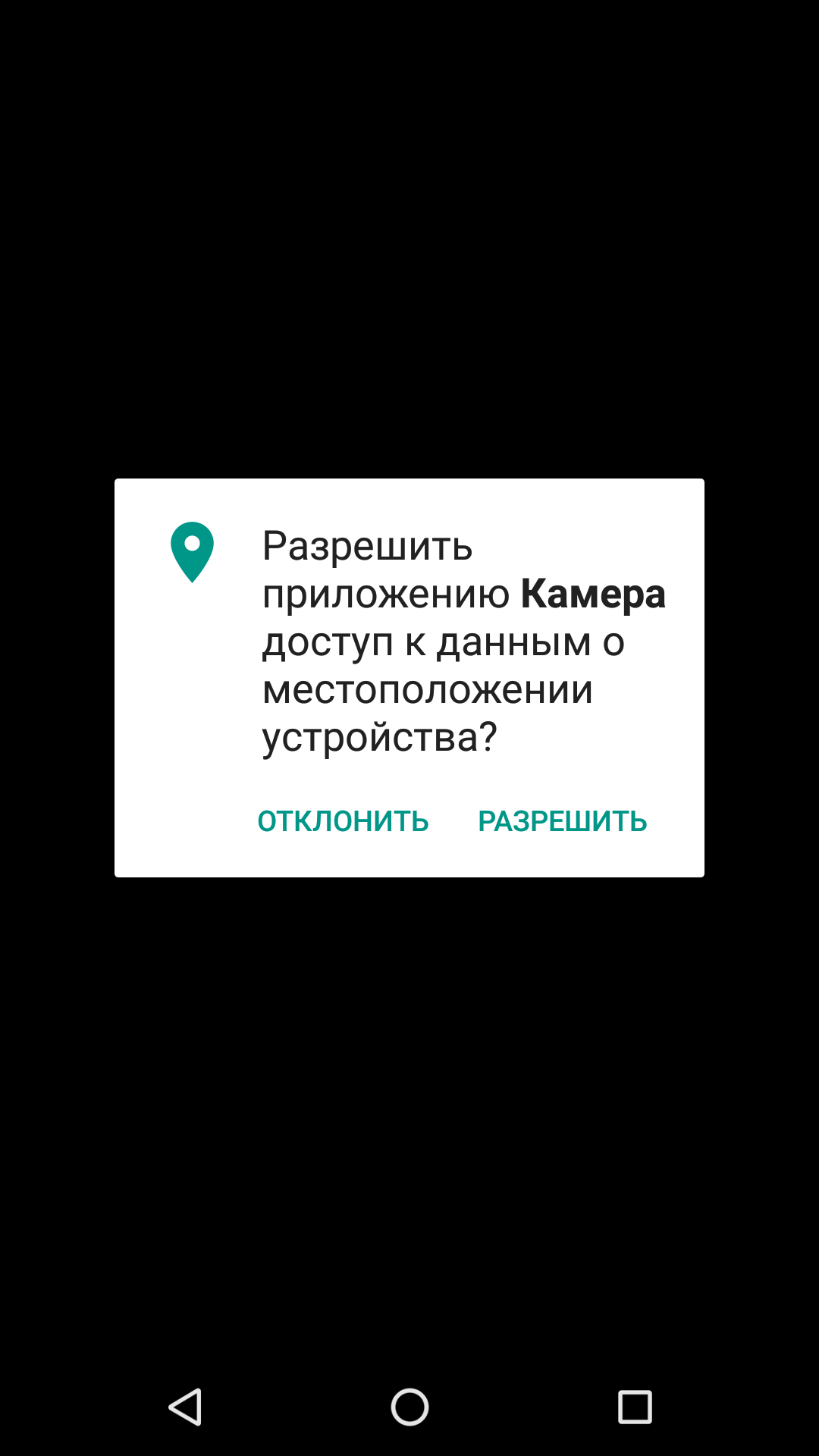

Permission prompts

“Android 6.0 finally added runtime app permissions—only took, what, ten years.” That’s how many users summed up one of Marshmallow’s headline features: those pop-ups saying, “App XXX wants to access the camera. Allow?” In short, Android users finally got real control over third‑party apps—the kind iPhone users had since iOS 6.

At first glance, it seems like a very necessary and sensible change. But dig a little deeper and its usefulness approaches zero. Let’s start with why such a system exists in the first place. Its purpose is simple: to let users control which parts of the smartphone an app can access and which it can’t. And here’s the first problem: if every installed app keeps asking for permission to access something, users quickly get conditioned to approve requests automatically.

Yes, for a certain group of privacy‑conscious users, such a system makes sense. However, for the vast majority it quickly becomes a nuisance—even for those who simply don’t want the apps they install to misuse smartphone features. These users generally stick to trusted software and avoid installing unknown apps from dubious sources.

Second, the permission request model itself is overly generic. Dozens of distinct permissions that apps could request have been collapsed into just seven. This means that, for example, if a messenger wants to intercept SMS to retrieve an authentication code (a common practice), it now requests the SMS permission, which automatically grants it the ability to send SMS and read the SMS database. Previously, during installation, the user could see a list of granular permissions and confirm the app only wanted to intercept incoming SMS; now their only choice is to give the app full access to all SMS functions at once.

Third: the new runtime permission model doesn’t apply to legacy apps. If an app wasn’t built targeting Android 6.0+ (targetSdkVersion=23), it won’t request permissions from the user at runtime to access protected features; it will behave exactly as it did before 6.0. And, importantly, you can still ship apps with a targetSdkVersion below 23 (and that won’t change anytime soon): anyone can install the latest Android Studio and build an app targeting Android 5.1 that will run fine on Android 6/7 and won’t prompt the user for runtime permissions.

Put differently, the permission model not only fails to protect you from apps that can turn your phone’s features against you, it also creates a false sense of security. The user may think they’re in control, but in reality they’re not.

|

|

| Request for camera access and all permissions of the Camera app | |

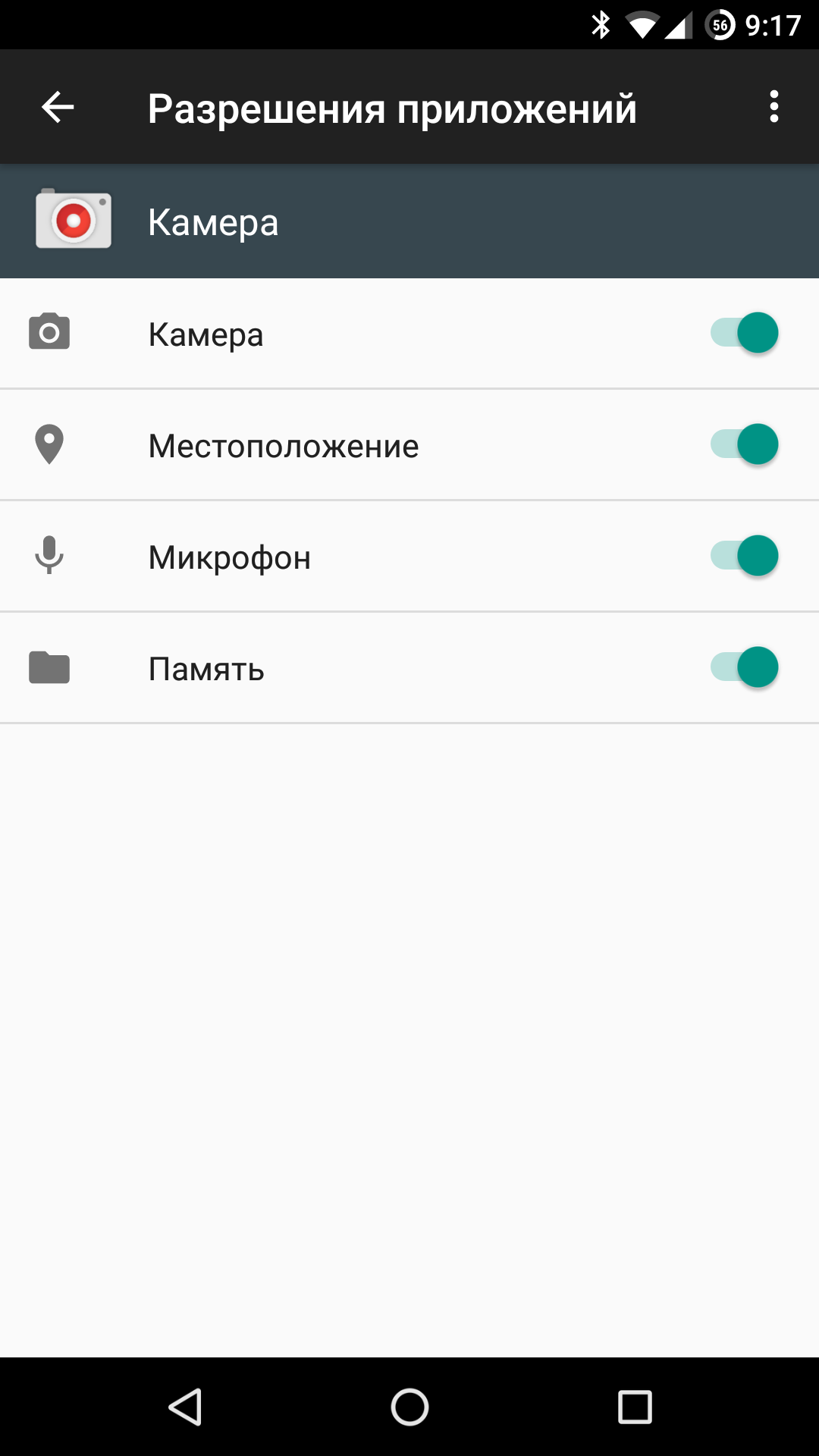

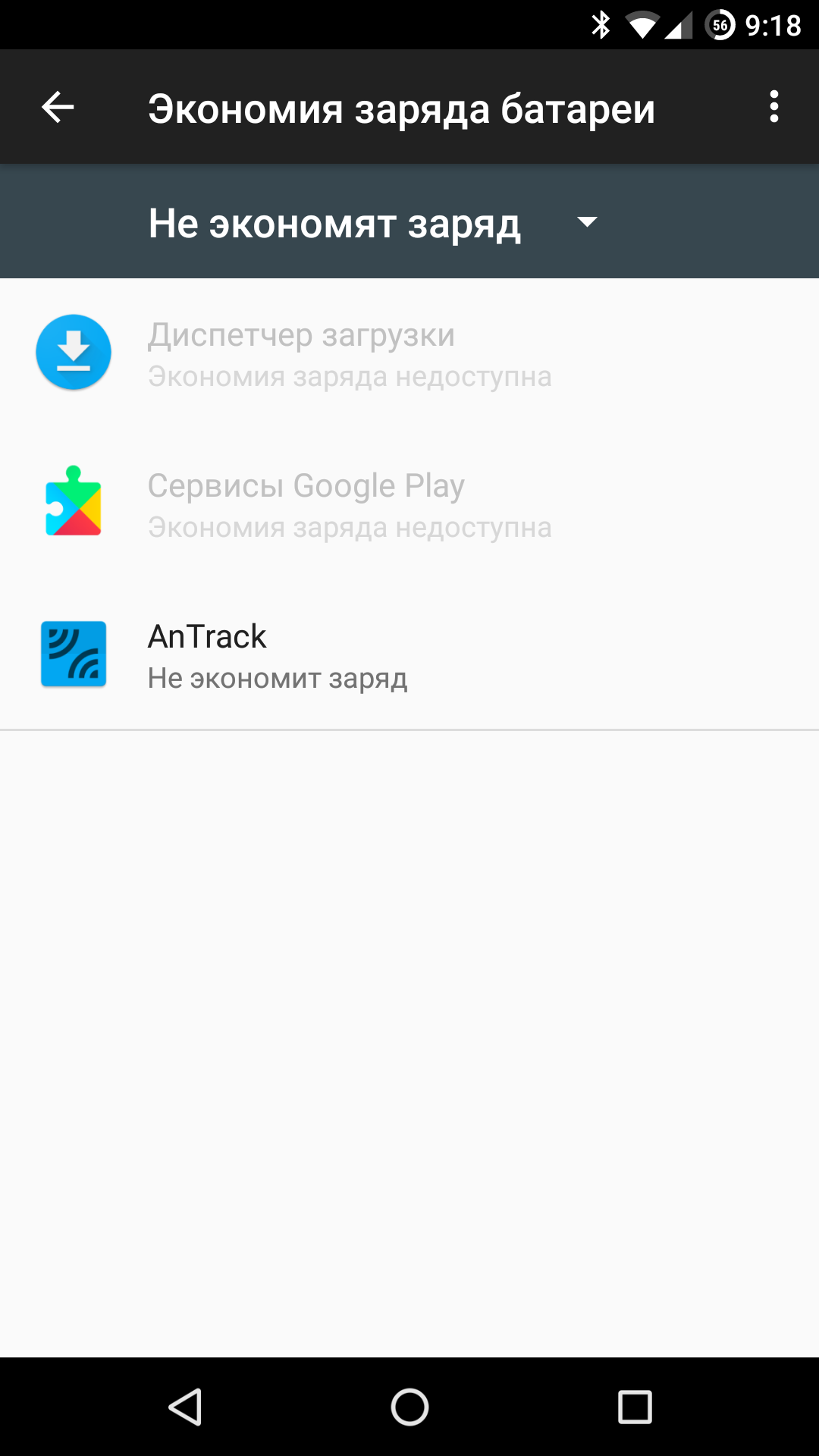

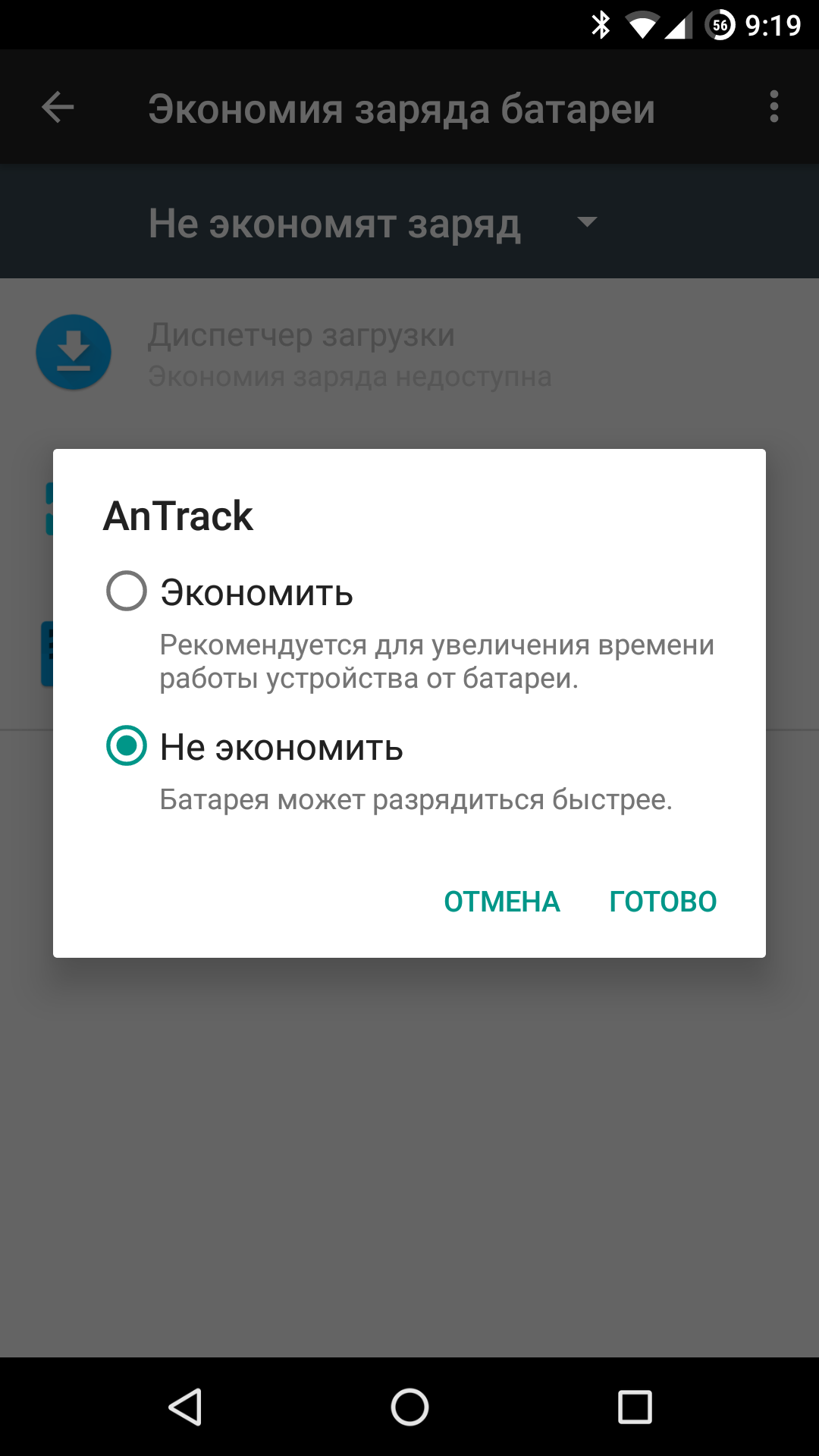

Power Saving

Android’s biggest advantage over other mobile OSes is the breadth and completeness of its developer tools and APIs. In other words, in spirit Android is much closer to a full-fledged desktop OS than iOS or Windows Mobile. Apps can run in the background; third-party apps are minimally constrained and can access system capabilities on par with stock software. The dialer, home screen, camera, and messaging app—users can replace any of them with third-party alternatives with virtually no restrictions.

Where there’s freedom, there’s responsibility. As Android grew in popularity, a serious issue emerged: many developers abused the platform’s capabilities and built apps that could dramatically shorten battery life. It’s not hard to do—just spin up a background service that acquires a wakelock (which prevents the device from sleeping) and keeps doing work continuously.

In most cases, that kind of software was the result of plain incompetence; in some, it was outright malicious. Either way, it cemented Android’s reputation as a battery hog, which forced Google to respond. Early countermeasures were fairly mild: revoking overly long wakelocks, batching tasks, and force-stopping services that ran too long. Ultimately, this led to the aggressive Doze power-saving mode in Android 6.0.

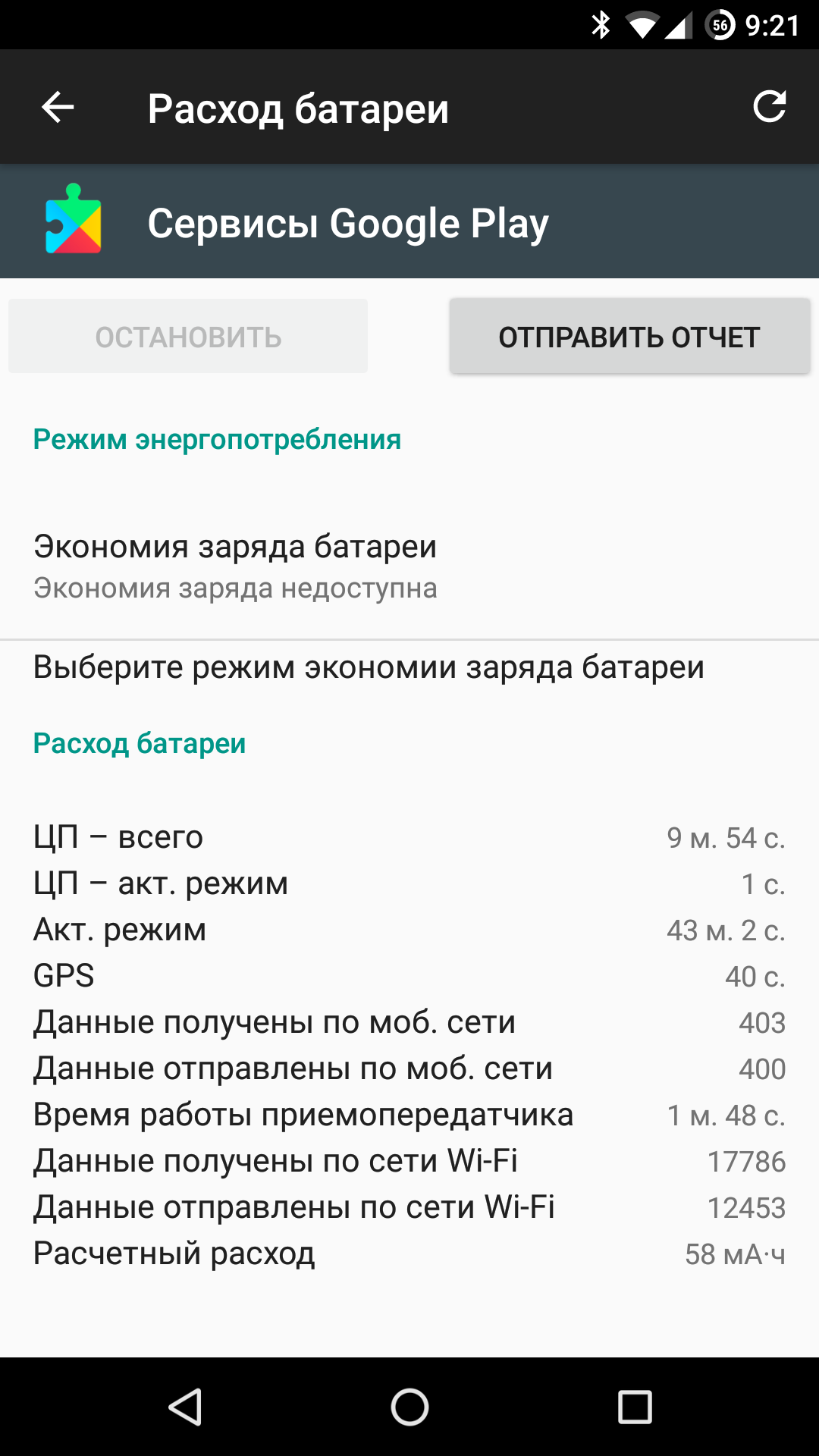

Doze is pretty straightforward. On Android 6.0, if the phone stays untouched and the screen off for about an hour, the system cuts off network access and puts all apps and services to sleep, ignoring wakelocks. From time to time it briefly wakes up—first after an hour, then at longer intervals—so services can do their work, and then it goes back to sleep. In addition to Doze, there’s App Standby, which applies similar limits on a per‑app basis when an app isn’t actively used, regardless of whether you’ve woken the phone or not.

In theory, Doze lets you minimize your smartphone’s power use so you don’t wake up to find the battery down by around 10%. But there are two problems. First: turning on Doze only makes a noticeable difference if your phone is loaded with lots of poorly written, battery-hungry apps. For users who are careful about what they install and don’t clutter their device with apps they’ll use once a year, it will have virtually no effect.

The second issue: Doze mode breaks the functionality of an entire class of apps many users rely on. Essentially all “server-side” software that lets you reach the phone over the network and get a response goes down the drain. SSH servers, web servers, device-tracking tools, and remote-control apps will all run extremely unreliably and with massive response delays (one to two hours or more) because of Doze.

To address this, Google offers developers two options: either use high-priority push notifications to wake the device, or ask users to whitelist the app from Doze mode. The catch with the first method is that it goes through Google’s servers and therefore requires Google Play Services on the device. That’s exactly why the Signal messenger won’t work on Amazon tablets and phones: it relies on push notifications solely to wake the device. Moreover, push notifications don’t solve the network access restrictions. In other words, after receiving a push, the app still can’t contact a third-party server until the user wakes the device or a Doze maintenance window opens.

The second option is problematic because the UI for exempting an app from Doze is buried quite deep (Battery → “Menu” button → Battery optimization → All apps), and it’s hard to get all users to follow those steps. And even if you exclude an app from Doze, there’s no guarantee it will behave properly in the background. It may be able to acquire wakelocks and use the network, but that doesn’t mean the system will actually wake it at the right moment. Which brings us back to push notifications: first, you have to wake the phone.

Lately, Google’s fight to protect users’ battery life has turned into a full-on crusade. They’re now explicitly urging developers to ditch background services in favor of the JobScheduler—a system that closely mirrors what apps get on iOS. Instead of running in the background, an app queues its tasks with JobScheduler and specifies the conditions under which they should run (time, network connectivity, charging state, and so on).

JobScheduler itself is a great idea, but if Google further restricts background app execution in the future, they’ll end up killing one of Android’s best qualities as an operating system.

|

|

| Doze mode control panel | |

Locking Down the Source Code

Android is an open-source operating system, and that’s one of Google’s main selling points for choosing it. The source code is fully available: anyone can study it or even build their own firmware from it—just like the developers of CyanogenMod (now LineageOS) and other custom ROMs.

What’s more, device makers don’t have to license Android from Google or pay royalties—anyone can use it. The only catch is that if they want to include the Play Store, they must preinstall most other Google apps and meet Google’s hardware and software requirements as outlined in the Google compatibility requirements. For example: implement a secure fingerprint scanner according to the spec, avoid breaking Android APIs, and equip the phone with the required sensors and components.

On the whole, these are reasonable demands for a company that gives its OS away for free and makes its money by monetizing access to services. The problem is, the more attention Google pours into its proprietary apps, the more it neglects their open counterparts in Android. Since Google Keyboard launched, the stock Android keyboard has barely evolved; the stock Android Camera doesn’t come close to Google Camera’s feature set; the same goes for the dialer, SMS app, email client, and home screen. And the old Google search bar, effectively replaced by the closed-source Google Now, is stuck in the Android 2.3 era.

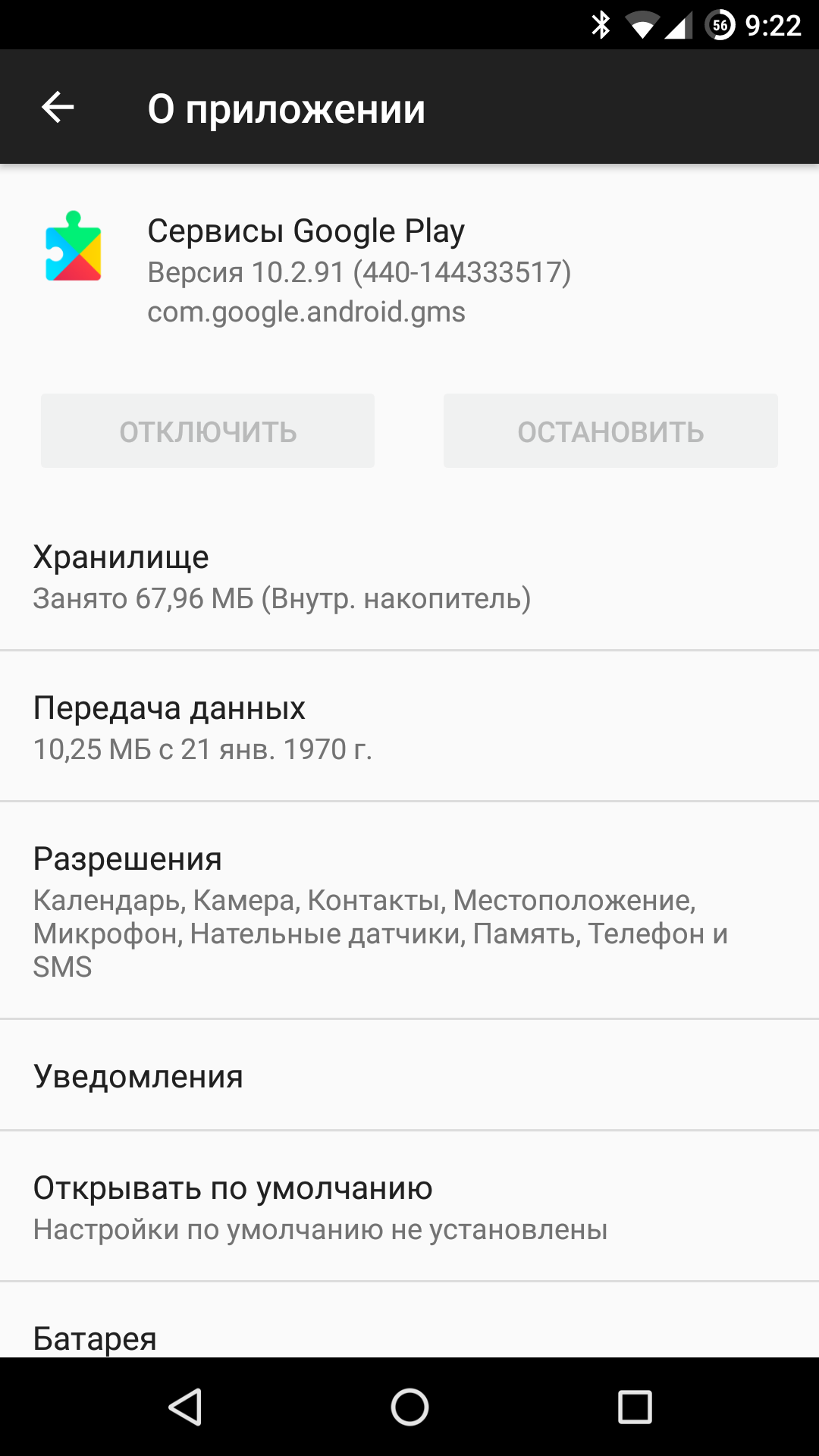

All right, those are just apps. You can replace them, and the important thing is the OS itself remains open, so the community can keep building clean custom ROMs. But here’s the catch: a huge chunk of functionality you might assume is standard Android isn’t Android at all—it’s Google Mobile Services, a system component installed alongside the Play Store and Google apps.

Google services power a wide range of core system features: signing in to your Google account; authentication (including two-factor and face-based); calendar and contacts sync; locating a lost or stolen phone; push notifications; cloud-based app malware scanning; and much more.

Originally designed as the smartphone’s link to the Google ecosystem, these services are now also used to deliver new functionality to older Android versions (unlike Android itself, Google can update them independently and silently across all connected devices). And these services are proprietary. In other words, Google doesn’t allow third-party audits and, per the terms of the user agreement, explicitly forbids installing alternative implementations.

Bottom line: We’re dealing with a nominally open system that Google can close off at any time thanks to its Apache 2.0 license. Many components are no longer maintained or have been abandoned, and others exist only as proprietary libraries, leaving no way to build alternatives.

|

|

| Google Services | |

Conclusion

In closing, I’d say that even though Android is steadily becoming a more locked-down OS, Google is implementing changes carefully, leaving ways to restore legacy functionality or otherwise work around the new mechanisms. So despite the overall trend, Android is still very much the Android we know—which is encouraging.