On August 13, the BBC Russian Service reported that the Russian Investigative Committee has acquired equipment capable of hacking the latest iPhone in just nine minutes. Hard to believe? I’m also surprised that such a reputable publication would release this information, yet it remains a fact.

I’d like to comment on the statement by expert Dmitry Saturchenko: “It takes more than a day for Israel’s Cellebrite to hack an iPhone 7 or 8, with the extracted data requiring substantial analysis. MagiCube processes the same iPhone in nine minutes, and the equipment is specifically designed to extract sensitive data from messaging apps, where 80–90% of interesting information is contained.”

An inexperienced reader might think that you can simply take any iPhone and extract information about messenger usage. However, this is not the case for several reasons. First, it’s important to note that MagiCube is a hard drive duplicator, whereas mobile devices are analyzed by a different system. Moreover, not just any iPhone will work; it must specifically be running iOS 10.0–11.1.2, meaning it hasn’t been updated since December 2, 2017. Next, you’ll need either user consent or to bypass the lock code using third-party tools like GrayKey or Cellebrite. Only after unlocking the phone can it be connected to the specialized equipment to retrieve the data.

Despite this, the news spread across numerous publications. “Experts” from SecurityLab, without bothering to link to the original source or even credit the author, wrote: “The Investigative Committee has procured equipment to gain access to communications.” “According to experts, it takes the MagiCube system about ten minutes to break into the latest iPhone models.”

So, what’s really going on? Is it possible to hack an iPhone 7 or 8 in just nine minutes? Does the iDC-4501 solution (as opposed to MagiCube, which is merely a hard drive duplicator) truly surpass the technologies of Cellebrite and Grayshift? Finally, how can an iPhone actually be hacked? Let’s try to understand what exactly the Investigative Committee has purchased, how and when it works, and what to do in the 99% of cases when the system doesn’t solve the task.

It Depends…

Before attempting to access an iPhone, let’s understand what can be done and under what conditions. Yes, we’ve had numerous publications, including some quite detailed ones, where we’ve described various methods to hack devices. But now, you have a black box in front of you. Which of the many methods and tools are you planning to use? Is it even possible to succeed, and if so, how much time will it take and what can you expect as a result?

Yes, much depends on the device model and the version of iOS installed on it (which, by the way, you still need to determine—and I’ll say in advance: it’s not guaranteed you’ll succeed). However, even an iPhone of a clearly identifiable model with a known iOS version can be in one of many states, and this will determine the set of methods and tools available to you.

Let’s start by agreeing that we’ll focus exclusively on iPhone generations equipped with 64-bit processors. This includes the iPhone 5S, all versions of the iPhone 6/6s/7/8/Plus, and the current flagship, the iPhone X. From a hacking perspective, these devices differ little, except for older generations if you have access to Cellebrite’s services.

Is a Lock Code Set?

Apple may implement the most robust encryption and create complex multi-layered security, but no one can protect users who claim they have “nothing to hide.” If an iPhone doesn’t have a lock code set, extracting data from it is a trivial task. As mentioned in a BBC article, the process can begin in just nine minutes. However, it will likely take longer, as copying 100 GB of data takes about two hours. What is required for this?

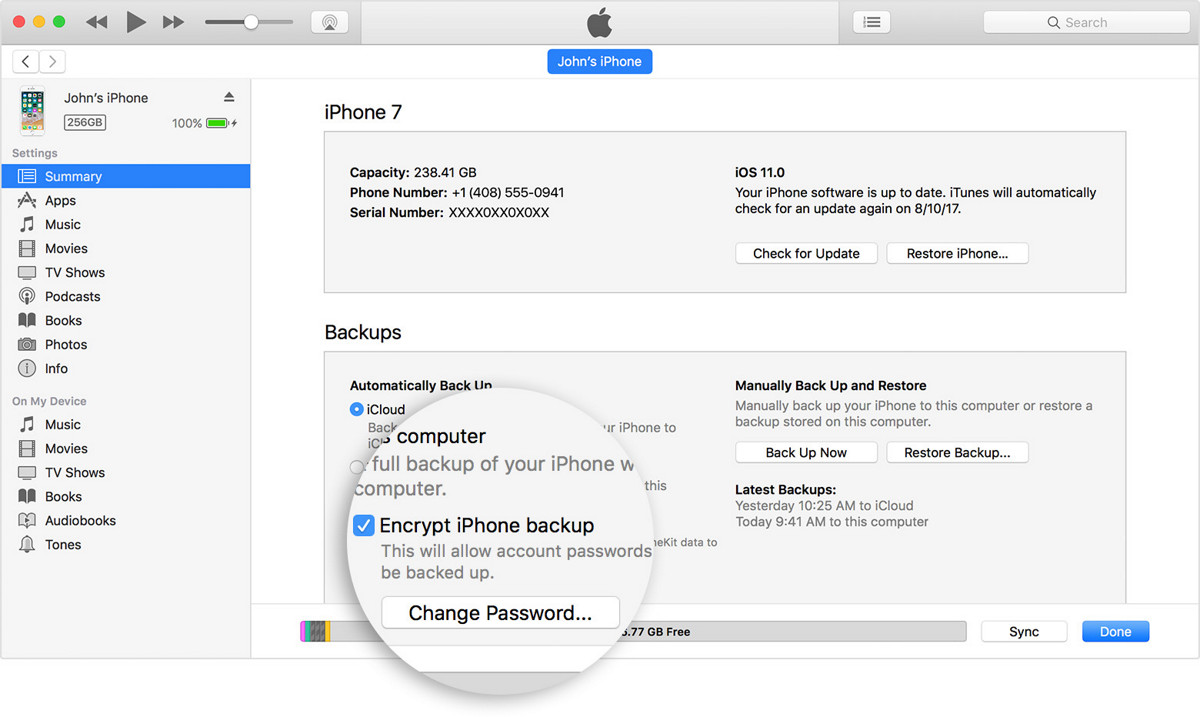

First, connect your phone to the computer, establish a trusted connection, and create a backup. You can use iTunes for this (make sure to disable two-way synchronization beforehand), but experts often prefer their own software.

Is There a Password Set on the Backup?

Not installed yet? Install it and create another backup!

Why set a password on a backup? The fact is that a significant portion of the information in iOS backups is encrypted even if the user has not set such a password. In these cases, a device-specific unique key is used for encryption. It’s better to set a known password for the backup; this way, the entire backup, including “secret” data, will be encrypted with that password. Interestingly, this also grants you access to the protected keychain storage, which means access to all user passwords saved in the Safari browser and many built-in and third-party apps.

What if there’s a password set on a backup, and you don’t know it? It’s unlikely for people with nothing to hide, but still? For devices running older versions of iOS (8.x–10.x), the only option is brute force. If the attack speed for iOS 8–10.1 was acceptable (hundreds of thousands of passwords per second on a GPU), starting with iOS 10.2, brute force is no longer viable: the speed doesn’t exceed a hundred passwords per second, even with a powerful graphics accelerator. However, you can try extracting passwords saved by the user, for instance, in the Chrome browser on a personal computer, and create a dictionary from them to use as a base dictionary for the attack. (Believe it or not, this simple tactic works about two out of three times.)

Devices running iOS 11 and 12 allow you to easily reset the backup password directly from the iPhone settings. Some settings, such as screen brightness and Wi-Fi passwords, will be reset, but all apps and their data, as well as user passwords in the keychain, will remain intact. If a passcode is set, you will need to enter it, but if not, resetting the backup password is just a matter of a few clicks.

What else can be extracted from a device with an empty lock code? Without resorting to jailbreaking, you can easily extract the following set of data:

- Complete information about the device

- User information, Apple accounts, phone number (even if the SIM card has been removed)

- List of installed applications

- Media files: photos and videos

- Application files (such as iBooks documents)

- System crash logs (which can include information about applications that were later uninstalled)

- The previously mentioned iTunes backup that can contain data from many (but not all) applications, along with user passwords for social networks, websites, authentication tokens, and much more.

Jailbreak and Physical Data Extraction

If the information extracted from the backup wasn’t enough, or if you couldn’t crack the password for the encrypted backup, jailbreaking is your remaining option. There are jailbreaks available for all versions of iOS 8.x, 9.x, and 10.0–11.2.1 (earlier versions are not considered). For iOS 11.3.x, the Electra jailbreak is available, which also works on earlier versions of iOS 11.

To install a jailbreak, you can use one of the publicly available tools such as Meridian or Electra, along with Cydia Impactor. There are alternative hacking methods, like privilege escalation without installing a public jailbreak by exploiting a known vulnerability. For iOS 10–11.2.1, this involves using the same vulnerability, with details and source code published by Google experts. All these methods share a common requirement: the iPhone must be unlocked and connected to a computer, with trusted relations established.

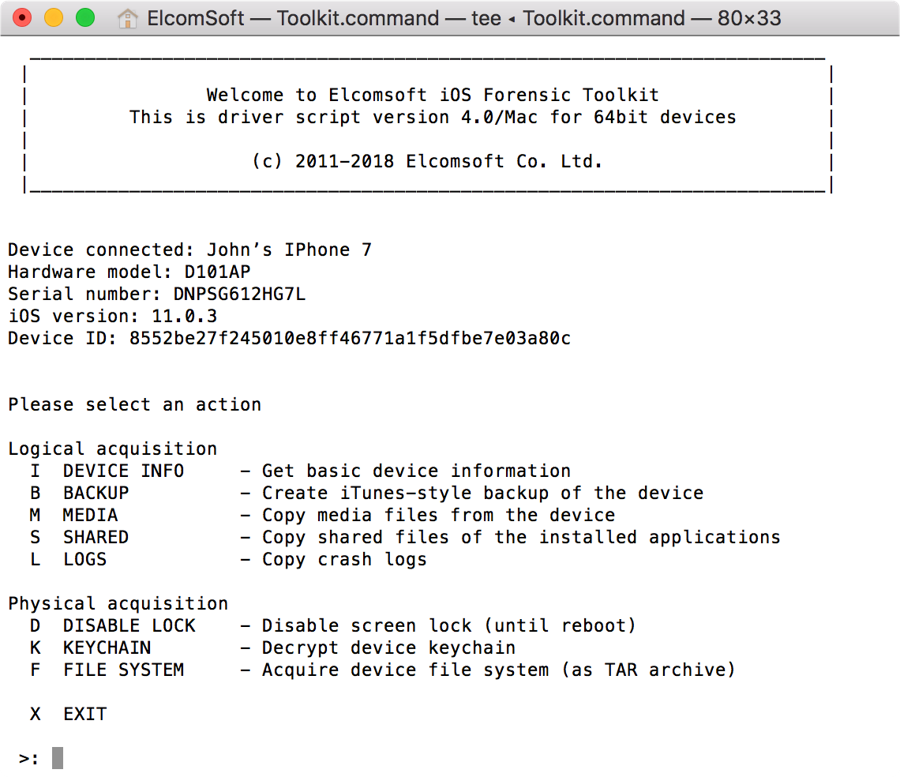

The next step is to extract the file system image. Ideally, this can be done by opening an SSH session with the phone and executing a series of commands on the iPhone. In more complex scenarios, you might need to manually set the appropriate paths in PATH or utilize a pre-made tool. The result will be a TAR file transferred through a tunneled connection.

If your smartphone is running iOS 11.3.x, you’ll need to manually install the jailbreak. To extract information, you can use the iOS Forensic Toolkit or a similar tool.

If your iPhone is running iOS 11.4 or a later version, you’ll need to postpone jailbreaking indefinitely—until the developer community discovers another undisclosed vulnerability. In the meantime, a backup will be useful to you, as well as extracting common application files, photos, media files, and some system logs.

Of course, not everything is included in a backup. For instance, Telegram chats and email messages aren’t saved, and the user’s location history is only sparsely recorded. Nevertheless, having a backup is still quite significant.

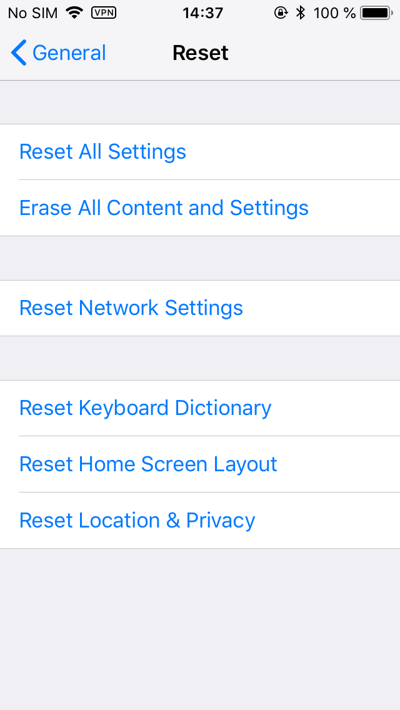

What if the user isn’t entirely careless and has actually set a lock code?

Even the most carefree users are compelled to use a passcode if it’s required by their employer’s security policy or if they want to use Apple Pay. There are two scenarios here: either the lock code is known or it isn’t. Let’s start with the simple one.

Is the Passcode Known?

If you know the lock code, you can practically do anything with the device. You can power it on and unlock it at any time. You can change the Apple ID password, remove the link to iCloud, and disable iCloud lock, enable or disable two-factor authentication, save passwords from the local keychain to the cloud and extract them. For devices with iOS 11 and newer, you can reset the backup password, set your own, and decrypt all the same passwords for websites, various accounts, and applications.

In iOS 11 and later versions, if a lock code is set, it will be required to establish a trusted relationship with a computer. This is necessary both for creating a backup (there may be other options, such as using a lockdown file) and for installing a jailbreak.

Can you jailbreak the device and extract the few but potentially valuable pieces of information for the investigation that aren’t included in the backup? This depends on the iOS version:

- iOS 8.x–9.x: Jailbreaks are available for almost all OS and platform combinations.

- iOS 10.x–11.1.2: Jailbreak utilizes a public exploit discovered by Google specialists. It works on all devices.

- iOS 11.2–11.3.x: Jailbreaks are available and can be installed.

- iOS 11.4 and above: Currently, no jailbreak is available.

info

So, the iDC-4501 system acquired by the Investigative Committee enables privilege escalation on iPhones running iOS versions from 10.0 up to and including 11.1.2, after which it can extract data from the device.

What if the passcode is unknown? In this case, the chances of successfully extracting any data start to diminish. However, all is not lost—this depends on the condition of the phone when it’s submitted for analysis and the version of iOS it is running.

Is the Device Screen Locked or Unlocked?

It’s not always the case that the police end up with a locked phone for which they know the unlock code. A typical scenario might involve a police officer saying, “Hand me your phone. Unlock it!” According to police officers themselves, if they speak with confidence, particularly at the scene of an incident, people often comply. After 10-15 minutes, “they start to think,” but by that time it’s too late: retrieving the unlocked device is unlikely. Furthermore, the police may have a warrant authorizing them to unlock the device using the user’s fingerprint or facial recognition, even against the owner’s will (however, obtaining the unlock code in the same manner might not be possible, depending on the jurisdiction).

Apple has integrated a feature in iOS that protects against certain police actions by limiting the period during which Touch ID and Face ID remain functional. After a specific amount of time, counted either from the last time the device was unlocked or from the last time the passcode was entered, the iPhone will prompt the user to enter their passcode when an attempt is made to unlock the device again.

We won’t delve into this topic in detail, especially since we’ve written about it before. It’s enough to mention that biometric sensors are disabled 48 hours after the last unlock, or eight hours if the user hasn’t entered the passcode in six days, or after five failed scan attempts, or after the user activates the SOS mode, which was introduced in iOS 11.

So, you’ve got an unlocked iPhone in your hands. What should you do?

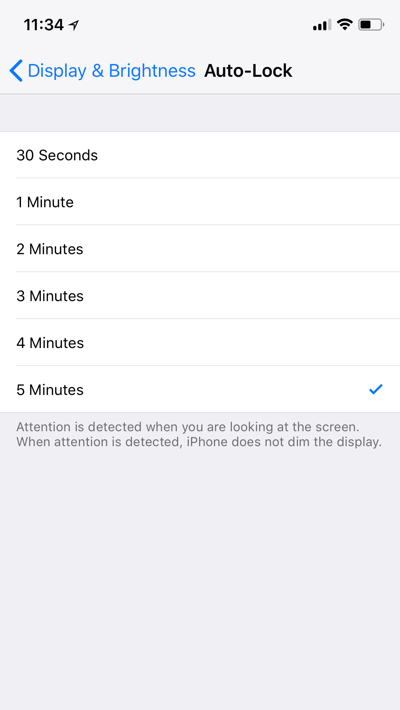

Try to disable the automatic screen lock in the settings. Be aware that if your phone is under a corporate Exchange policy or MDM (Mobile Device Management), this option might be restricted.

Connect the phone to a computer and attempt to establish a trusted relationship. For iOS versions 8 to 10, simply confirm the “Trust this computer” prompt. However, for iOS 11 and above, you’ll need to enter the passcode. If the passcode is unknown, try to find the “lockdown” file on the user’s computer (we’ve previously discussed what it is and where it’s stored).

If you successfully establish a trusted relationship, create a backup.

If you’re unable to establish a trusted relationship and the lockdown file is either not found or has expired, you’ll have to use the GrayKey system to decipher the passcode or utilize Cellebrite services (Note that Cellebrite services are only available to law enforcement and specific government agencies in certain countries).

For more details on lockdown files, you can read the article Acquisition of a Locked iPhone with a Lockdown Record. In brief: to start exchanging data with a computer, an iPhone requires setting up a trusted connection, during which a pair of cryptographic keys is created. One key is stored in the device itself, while the other is transferred to the computer and stored there as a regular file. If this file is copied to another computer or provided to the phone using special software, the phone will believe it is communicating with a trusted computer. These files are stored here:

- In Windows Vista, 7, 8, 8.1, and Windows 10, it is located at

%ProgramData%\. For example, the full path would look something like this.Apple\ Lockdown - In Windows XP, the file is at

%AllUsersProfile%\. The full path might look like this.Application Data\ Apple\ Lockdown - In macOS, the file is located at

/.var/ db/ lockdown

The file name includes a unique device identifier (iPhone or iPad). It’s quite easy to find out—just make a request using the Elcomsoft iOS Forensic Toolkit. The UUID will be saved in an XML file.

<?xml version="1.0″ encoding="UTF-8″?><!DOCTYPE plist PUBLIC "-//Apple//DTD PLIST 1.0//EN" "http://www.apple.com/DTDs/PropertyList-1.0.dtd"><plist version="1.0"> <dict> <…>

<key>UniqueDeviceID</key> <string>0a226c3b263e004a76e6199c43c4072ca7c64a59</string> </dict></plist>The lifespan of lockdown files in iOS 11 and newer versions is limited and not exactly known. It has been experimentally determined that devices that have not connected to a trusted computer for more than two months sometimes require re-establishing trusted relationships, meaning old files may not work.

info

Returning to the story with the Investigative Committee: the acquired iDC-4501 system enables privilege escalation on an unlocked iPhone running iOS versions from 10.0 up to and including 11.1.2, after which data can be extracted from the device. For iOS 11.0–11.1.2, it may be necessary to either enter the passcode or use a lockdown file—this detail is not clarified in the system’s documentation, nor is there any mention of the ability to bypass the passcode on any iPhone running iOS later than 7.x.

You can gain even more information if you have access to a user’s biometric data, such as their fingerprint or facial recognition. This would allow you to view passwords stored in the local keychain.

Is the iPhone On or Off?

A seemingly simple detail can be incredibly important. If an iPhone is turned on, it’s highly likely that the owner has unlocked the device at least once since it was powered on. This, in turn, means there’s access to the encrypted user partition, which includes installed apps and their data, system logs, and much more.

On a phone that has been unlocked at least once, services like AFC, backup creation, and access to data that applications have permission to access are operational. Additionally, photos can be extracted. None of this requires unlocking the phone: with some luck, you can use a lockdown file extracted from the user’s computer. If such a file isn’t available, you can attempt to unlock the phone using the Touch ID fingerprint sensor or the Face ID scanner.

So, if you have an unlocked iPhone with a locked screen, you might want to try the following.

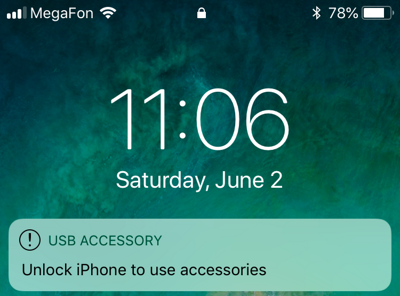

Connect the phone to a computer. If your phone shows the message “Unlock iPhone to use accessories” and the computer doesn’t detect the device, you’re likely dealing with iOS 11.4.1 or later. If more than an hour has passed since the device was last unlocked, Apple’s USB Restricted Mode might be activated. This was Apple’s response to prevent illegal access services like GrayKey and Cellebrite from bypassing passcodes. Once in this mode, neither the lockdown file nor tools like GrayKey or Cellebrite can bypass the lock. Rebooting or attempting firmware recovery with data preservation won’t help either. The only way to unlock the phone at this point is by using Face ID or Touch ID (which have time limitations) or by entering the correct passcode.

Gather device information. If the phone connects to the computer, the first step is to gather information about the device. In the Elcomsoft iOS Forensic Toolkit, this is done with the ‘Information’ command. Even without establishing a trusted connection, you can glean details such as the iOS version, model identifier, serial number, and possibly the user’s phone number, even if the SIM card is removed. Depending on the iOS version, different methods of accessing user data will be available.

Utilize a lockdown file. If the phone connects and you have access to a lockdown file from the user’s computer, you’re in luck. This file can assist in creating a new backup without needing to unlock the phone. We’ve addressed lockdown files before: if the file is valid, you can retrieve extended device information (as long as the iPhone hasn’t been unlocked at least once after booting). However, if the phone has been unlocked at least once after startup, the lockdown file allows extraction of media files (photos and videos), crash logs, application files, and a fresh backup (note: if a backup password is set, it can’t be reset without the passcode).

But what if you have a typical black rectangle with no signs of life? If you need to hack a turned-off iPhone, you’ll still need to find out the passcode. The fact is, the user data partition on an iPhone is encrypted, and the encryption key is dynamically generated based on a hardware key and the data entered by the user—the passcode itself.

Even if you extract the memory chip from the phone, it won’t help you at all: the data is encrypted, and there is no access to it. Furthermore, if the iPhone is running iOS 11.4.1 or later, there is a high likelihood that you won’t be able to connect the device to a computer until you enter the correct password. More precisely, you’ll be able to physically connect it, but data transfer via USB will be blocked — you won’t even be able to obtain device information or determine which iOS version is running on it.

So, you have a locked phone that can be connected to a computer. Shall we try to bypass the lock code?

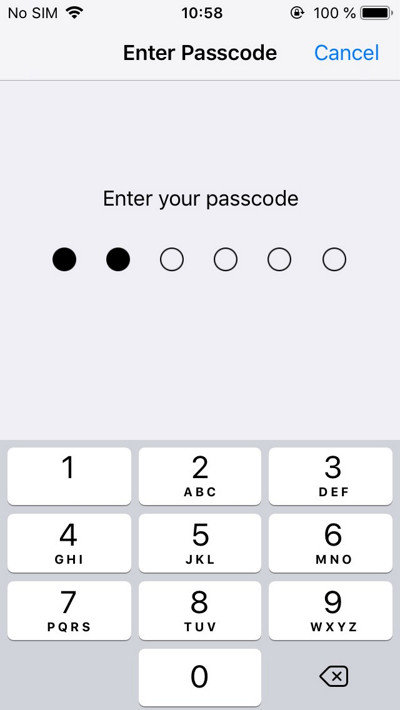

When Can a Screen Lock Code Be Hacked?

Now we get to the most intriguing part. Is it possible to hack an iPhone in nine minutes? Or in a day? Or in general? If the phone is locked and the passcode is unknown, much will depend on the device’s condition. Let’s examine all potential scenarios, organized by increasing complexity.

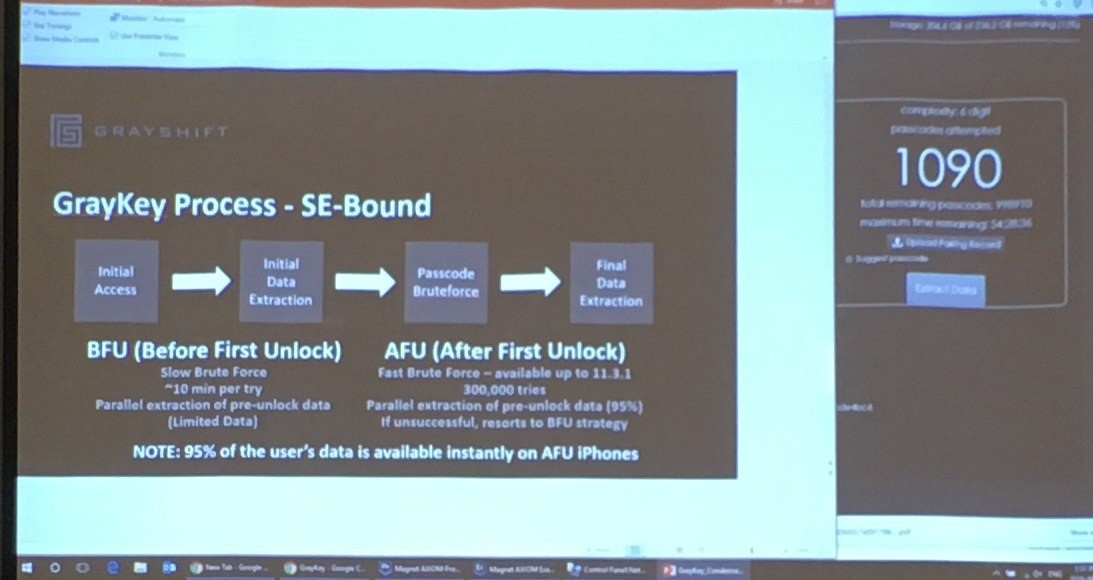

If the phone is running an old version of iOS (prior to 11.4) and has been unlocked by the user at least once since being powered on: In these favorable conditions, you can use GrayKey or Cellebrite services (if you represent law enforcement). The brute-force speed will be high: a four-digit passcode can be cracked in less than an hour, and the speed for six-digit codes will be fast for the first 300,000 attempts. After that, the speed will significantly decrease due to Secure Enclave protection.

If the phone is running an old version of iOS (prior to 11.4) and has not been unlocked once since being powered on, or the phone is running iOS 11.4 (regardless of whether it has been unlocked), or iOS 11.4.1 and above (regardless of whether it has been unlocked, but USB Restricted Mode has not been activated—meaning it has been less than an hour since the last unlock or the phone is connected to a digital adapter to prevent lockout): In all these scenarios, the brute-force speed will be very slow. Four-digit passcodes could take up to a week to crack, while six-digit codes could take up to two years.

If the phone is running iOS 11.4.1 or newer, and USB Restricted Mode is activated: Unfortunately, the only available options are to try unlocking the phone with Touch ID or Face ID, or to enter the correct passcode. Automated brute-force attacks are not possible, nor is bypassing data erasure after ten incorrect attempts (if this option is enabled by the user).

How Unlock Codes Are Cracked

For modern devices running iOS 10 and iOS 11, there are exactly two solutions that allow bypassing the screen lock code. One of these solutions was developed by Cellebrite and is offered as a service exclusively available to law enforcement agencies with the appropriate warrant. To unlock the screen code, the phone must be sent to the company’s service center. They also provide a special utility to check whether the code can be brute-forced in principle. Little is known about Cellebrite’s solution, as the company carefully guards its secrets.

Another solution is called GrayKey, developed by the company Grayshift. This tool is provided to law enforcement agencies and some other organizations that have the capability to carry out password cracking independently. We have more detailed information about GrayKey.

Grayshift’s solution doesn’t utilize DFU mode (which was previously used to hack older iPhones) and instead loads an agent in system mode. The brute-force attack can be initiated on devices that have been unlocked at least once after being turned on or rebooted, as well as on “cold” devices that have just been powered on. The speed of this brute-force attack varies not just by multiples but by orders of magnitude.

If a device has been unlocked at least once after booting up, brute-forcing all the four-digit passwords is possible within 30 minutes. However, if the device has just been turned on, an attack on the four-digit code can last up to 70 days. As for cracking six-digit digital passwords without a quality wordlist, it’s impractical: a full brute-force attempt would take decades since the device allows only one attempt every ten minutes. There is a caveat with six-digit codes, though: after 300,000 attempts, the brute-force speed drastically decreases, and the device switches to a slow brute-force mode.

Sounds good (or bad, depending on your perspective)? Unfortunately, “fast” brute-force attacks are only possible for iOS versions up to 11.3.1. If a user has updated their iPhone even once after May 29, 2018, the device will be running iOS 11.4 or later. With these versions, the “fast” brute-force method using GrayKey is not possible. For iOS 11.4 and beyond, the password guessing speed with GrayKey is limited to one password every ten minutes. This means that cracking a device with a six-digit PIN code (which modern iOS versions recommend setting by default) is virtually impossible.

USB Restricted Mode

This mode has been written about several times, including in our magazine. Starting from iOS 11.4.1, iPhone and iPad devices completely block data exchange via the USB protocol one hour after the device is unlocked or disconnected from an accessory. This mode was likely introduced to counteract GrayKey and Cellebrite systems, which can crack a device’s passcode using an unknown Apple exploit. The mode has proven quite effective: devices with a locked port cannot be connected to the system, and the code cracking process does not start.

Is it possible to bypass USB protection mode? Firstly, to activate data transfer, it is enough to unlock the phone, for example, using a fingerprint (which, in turn, is also not foolproof—see above). Secondly, the restriction can be avoided by connecting the phone to a compatible accessory (not all accessories will work!) within an hour after the last lock, even if the phone is in a locked state.

In other words, when confiscating devices, a police officer will need not only to place the phone in a Faraday cage but also to connect it to a compatible accessory (such as the official Apple Lightning to USB 3 adapter with an additional charging port). If this is not done, the phone will enter a protective mode after just one hour, and initiating a brute force attack on the lock codes will not be possible.

Security is an endless race. Apple is aware of the potential to bypass the USB restricted mode and is developing technology to block data transfer immediately after the device is locked. If this feature is included in a future iOS update (which is uncertain), USB data transfer will automatically be deactivated as soon as the device’s screen is locked, meaning you’ll need to unlock the device to connect it to accessories or computers.

For user convenience, exceptions have been made for the audio jack adapter (its connection does not affect the activation of USB Restricted Mode) and for charging from regular chargers, but not from a computer port.

What to do if the phone is locked, broken, or missing

How can one extract data from a locked or broken device? Similarly to how you would from a device that doesn’t physically exist: through iCloud. With the proper warrant, law enforcement can request all data from a user’s account from Apple, including cloud backups. For everyone else, another method is available: using the user’s Apple ID and password.

How can you obtain an Apple ID and password? You could, for instance, run Elcomsoft Internet Password Breaker on the user’s computer to see if the Apple ID or iCloud password (they will be the same) can be found there. Alternatively, you can try resetting it via email. To bypass two-factor authentication, if it’s activated, you might receive an SMS on a SIM card extracted from the same iPhone.

Finally, you can search the user’s computer for a so-called authentication token, which allows you to access iCloud without requiring a login, password, or secondary authentication factor. Of course, the chances of finding an authentication token or the password for an Apple ID or iCloud account aren’t guaranteed for every case, and the SIM card might be protected by its own PIN code. However, if you manage to bypass these obstacles, you can use specialized software (such as Elcomsoft Phone Breaker) to download the following items:

- Cloud backups (up to two per device on the account)

- Synchronized data, including a buffet of options: open pages in Safari and browsing history, calendars, notes, contacts, call logs, and all text messages including iMessage (though for iMessage, both a password and the passcode from one of the user’s trusted devices are required). If the user owns a Mac, synchronized files from the computer may be included, and even an escrowed key for decrypting the FileVault 2 partition.

- If iCloud Photo Library is enabled, then photos as well.

- If iCloud Keychain is active, then a user’s passwords for various online resources are also available. This requires entering the passcode of one of the user’s trusted devices.

Conclusion

If you’ve read this article, you’ve probably already figured out whether it’s possible to hack an iPhone in nine minutes using a “magic cube” or a specialized unnamed complex for hacking mobile devices. Yes, it is possible—if the phone is running iOS 10–11.2.1 (meaning it hasn’t been updated to iOS 11.2, released on December 2, 2017), and if it was conveniently unlocked by the owner, lacks a passcode, or if the passcode is known.

If a user has updated their device even once after December 2 of last year, the trick won’t work. If the phone is locked with an unknown password, the trick won’t work either; the lock code will need to be cracked using a separate solution like GrayKey or Cellebrite (which, by the way, will independently extract all data if successful). Moreover, if the phone is locked and running a fresh version of iOS 11.4.1, and more than an hour has passed since the last unlock or connection to an accessory, even these services will not be of help.

What are the chances that a phone is running iOS 11.4.1? According to independent sources (Apteligent and StatCounter), iOS 11.4.x accounts for about 61 to 63% of devices. Unfortunately, these sources do not differentiate between iOS 11.4 and 11.4.1, but historical data suggests that by the end of August 2018, roughly 57% of devices were using iOS 11.4.1. It can be confidently stated that currently, these 57% of devices cannot be hacked through technical means alone, unless the user is forced to unlock the device or provide the passcode.

What can we expect in the near future? iOS 12 is set to be released soon, and it’s likely that nearly all iOS 11 users, as well as many with older devices, will make the switch because the new system version performs faster than its predecessors. Some reviewers have even described the beta version as giving “new life to old devices,” which holds a lot of truth. In particular, the widespread adoption of iOS 12 will also mean the extensive use of the USB Restricted Mode.

A vulnerability has already been found and confirmed for iOS 11.4, and a jailbreak can be expected any day now. For iOS 11.4.1, no vulnerabilities have been discovered yet, but we consider the likelihood of finding them to be high. However, it may take some time.

In the beta versions of iOS 12, no critical vulnerabilities have been found yet. However, we believe there is still a high likelihood of them being discovered.