A bit of rambling

Imagine you get your hands on a malware sample. You spin it up in an emulator to analyze its behavior. But in the emulator it behaves nothing like it does on a real device and shows no suspicious activity—the malware can detect that it’s running in an emulated environment.

You suspect as much, so you decide to run the malware under a debugger (after unpacking the sample and adding android: to AndroidManifest.) to figure out exactly how it detects an emulator. Another snag: it can tell it’s being debugged and just crashes on startup. Next step: static analysis with a decompiler and disassembler, patching to remove the debugger and emulator checks, then more patching to fix errors, and so on.

Now imagine you have a tool that lets you disable all those checks on the fly while the app is running—simply by rewriting the verification functions in JavaScript. No smali disassembly listings, no low-level code edits, no app rebuilds; you just attach to the live process, locate the right function, and overwrite its body. Not bad, right?

Frida

Frida is a dynamic instrumentation toolkit—a set of tools that lets you inject your own code into other applications on the fly. Its closest counterparts are the well-known Cydia Substrate for iOS and the Xposed Framework for Android—the frameworks that made “tweaks” possible. What sets Frida apart is its focus on rapid, real-time code modification. That’s why it uses JavaScript instead of Objective-C or Java, and why there’s no need to package tweaks as full apps. You simply attach to a process and change its behavior using an interactive JS console, or instruct it to load a previously written script.

Frida works with apps on all major operating systems, including Windows, Linux, macOS, iOS, and even QNX. Here, we’ll use it to modify Android applications.

So, here’s what you need:

- A machine running Linux. You can use Windows, but if you’re pentesting Android apps, Linux is preferable.

- adb installed. On Ubuntu/Debian/Mint, install it with:

sudo.apt-get install adb - A rooted smartphone or an emulator running Android 4.2 or later. Frida can work on non-rooted devices, but you’ll have to modify/repackage the target app’s APK, which is a hassle.

First, let’s install Frida:

$ sudo pip install frida

Next, download the Frida server, which you’ll need to install on your smartphone. You can find it on GitHub; its version must exactly match the version of Frida you installed on your computer. At the time of writing, that was 10.6.55. Download:”

$ cd ~/Downloads

$ wget https://github.com/frida/frida/releases/download/10.6.55/frida-server-10.6.55-android-arm.xz

$ unxz frida-server-10.6.55-android-arm.xz

Connect your smartphone to your computer, enable USB debugging (Settings → Developer options → USB debugging), and push the server to the device.

$ adb push frida-server-10.6.55-android-arm /data/local/tmp/frida-server

Now connect to the phone via adb , set the required permissions on the server, and start it:

$ adb shell

> su

> cd /data/local/tmp

> chmod 755 frida-server

> ./frida-server

Getting Started

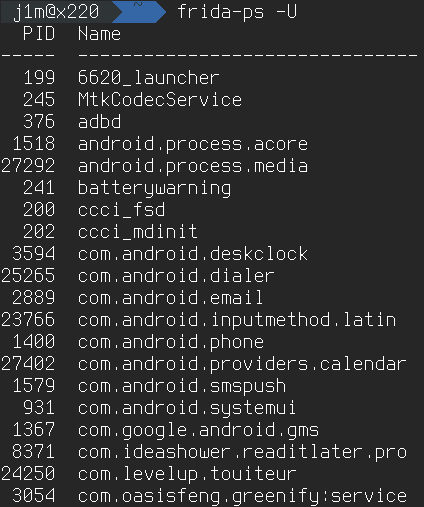

Okay, Frida is installed on the computer, and the server is running on the smartphone (don’t close the terminal with the running server). Now we need to verify everything is working as expected. For that, we’ll use the frida-ps command:

$ frida-ps -U

The command should list all processes running on the smartphone (the -U flag means USB; without it, Frida will list processes on the local machine). If you see this list, everything is set up correctly and you can move on to more interesting tasks.

To start, let’s trace some system calls. Frida lets you hook any native function, including Linux kernel syscalls. As an example, we’ll track the open( system call, which opens files for reading and/or writing. Let’s run a trace on Telegram:

$ frida-trace -i "open" -U org.telegram.messenger

Grab your phone and poke around the Telegram interface a bit. The screen should start filling up with messages along the following lines:

open(pathname="/data/user/0/org.telegram.messenger/shared_prefs/userconfing.xml", flags=0x241)

This line means that Telegram opened the file userconfig. inside the shared_prefs directory within its private app directory. On Android, the shared_prefs directory is used for storing settings, so it’s easy to infer that userconfig. contains the app’s configuration. Another line:

open(pathname="/storage/emulated/0/Android/data/org.telegram.messenger/cache/223023676_121163.jpg", flags=0x0)

It’s even simpler: Telegram aggressively caches downloaded data, so when it needed to display the image, it pulled it from its cache.

open(pathname="/data/user/0/org.telegram.messenger/shared_prefs/stats.xml", flags=0x241)

Another file in the shared_prefs directory. Looks like usage statistics.

open(pathname="/dev/ashmem", flags=0x2)

Looks odd, doesn’t it? It’s actually simple. The / file is virtual and is used to exchange data between processes and the system via the Binder IPC mechanism. In plain terms, this line means Telegram asked Android to perform some system function or retrieve information. You can safely ignore lines like this.

Writing the code

We can intercept calls to any other system calls as well—for example, connect(, which is used to establish connections to remote hosts:

$ frida-trace -i "connect" -U com.yandex.browser

However, in this case the output won’t be very informative:

2028 ms connect(sockfd=0x90, addr=0x94e86374, addrlen=0x6e)

2034 ms connect(sockfd=0x90, addr=0x94e86374, addrlen=0x6e)

The reason is that the second argument to the connect( system call is a pointer to a sockaddr structure. Frida can’t parse it, so it prints the address of the memory region where that structure resides. But we can change the code Frida executes when it hooks a system call or function. Which means we can parse sockaddr ourselves!

When you ran the frida-trace command, you probably noticed a line that looked something like this:

connect: Auto-generated handler at "/home/j1m/__handlers__/libc.so/connect.js"

This is the automatically generated hook code that Frida executes when the target app calls the specified function. It’s what produces those uninformative lines we saw. By default, the code looks like this:

onEnter: function (log, args, state) { log("connect(" + "sockfd=" + args[0] + ", addr=" + args[1] + ", addrlen=" + args[2] + ")");},You can see that the hook simply outputs the second argument as-is. But we know the second argument of the connect( system call is a pointer to a sockaddr structure—that is, just a memory address. The sockaddr structure itself looks like this:

struct sockaddr { unsigned short sa_family; // address family, AF_xxx char sa_data[14]; // 14 bytes of protocol address};For AF_INET sockets—the ones we need—it looks like this:

struct sockaddr_in { short sin_family; // e.g. AF_INET, AF_INET6 unsigned short sin_port; // e.g. htons(3490) struct in_addr sin_addr; // see struct in_addr, below char sin_zero[8]; // zero this if you want to};struct in_addr { unsigned long s_addr; // load with inet_pton()};In other words, the IP address is located in this struct at an offset of 4 bytes (short sin_family + unsigned short sin_port) and takes up 8 bytes (unsigned long). That means we need to add 4 to the base address, then read 8 bytes from the resulting address and parse them to get a dotted string IP address. We’ll do this by replacing the original hook with the following:

onEnter: function (log, args, state) { var addr = args[1].add("4") var ip = Memory.readULong(addr) var ipString = [ip & 0xFF, ip >>> 8 & 0xFF, ip >>> 16 & 0xFF, ip >>> 24].join('.') log("connect(" + "sockfd=" + args[0] + ", addr=" + ipString + ", addrlen=" + args[2] + ")");},Note that we parse the address from the end—i.e., we reverse it. This is necessary because all modern ARM processors use little-endian byte order. Also note the Memory class and the add( method; these are part of the Frida API.

Save the file and rerun frida-trace:

connect(sockfd=0xbb, addr=173.194.222.139, addrlen=0x10)

connect(sockfd=0xba, addr=74.125.205.94, addrlen=0x10)

Voilà. There’s one caveat. Since our code can’t distinguish between AF_UNIX, AF_INET, and AF_INET6 sockets and treats them all as AF_INET, it will sometimes print non-existent addresses. In other words, it will try to parse an AF_UNIX socket filename as an IP address (or try to render an IPv6 address as IPv4). Filtering out such addresses is easy—they usually come in clusters and repeat often. In my case, it was the address 101..

Injecting

Of course, Frida’s capabilities go far beyond hooking native functions and system calls. If we look at the Frida API referenced earlier, we’ll see the Java object. With it, we can intercept calls to any Java objects and methods, which means we can modify virtually any aspect of an Android app’s behavior (including apps written in Kotlin).

Let’s start with something simple—figure out all the classes loaded into the app. Create a new file (call it enumerate.) and add the following lines:

Java.perform(function() { Java.enumerateLoadedClasses({ onMatch: function(className) { console.log(className); }, onComplete: function() {} });});This is a very simple snippet. First, we call Java., which means we want to attach to the Java VM (or Dalvik/ART on Android). Then we call Java. and pass it two callbacks: onMatch( is invoked when a class is found, and onComplete( runs at the very end (as you can see, we don’t need that callback, so we leave it empty).

Run:

$ frida -U -l enumerate.js org.telegram.messenger

On the screen, we see a long, seemingly endless list of classes—some belong to the app itself, but the vast majority are standard Android framework classes (Android maps the entire framework into every process in a copy-on-write fashion).

That list isn’t particularly interesting to us. What’s far more interesting is that you can inject your own code into any of these classes—in fact, you can rewrite the body of any method in any of them. For example, consider the following code:

Java.perform(function () { var Activity = Java.use("android.app.Activity"); Activity.onResume.implementation = function () { console.log("onResume() got called!"); this.onResume(); };});First, we use Java. to obtain a wrapper for the android. class. Then we override its onResume( method, calling the original method (this.) at the end.

Anyone familiar with Android app development knows that the Activity class represents an app’s screens. It exposes many methods, including onResume(. This is a lifecycle callback that runs when the activity comes to the foreground—both the first time it’s shown and when you return to it.

If you load this script in Frida, start Telegram, exit it, and then reopen it, you’ll notice that each time you return to Telegram the terminal prints “onResume() got called!”.

In exactly the same way, we can intercept button presses:

Java.perform(function () { MainActivity.onClick.implementation = function (v) { consle.log('onClick'); this.onClick(v); }});Here’s an example of logging every URL the application requests:

Java.perform(function() { var httpclient = Java.use("com.squareup.okhttp.v_1_5_1.OkHttpClient"); httpclient.open.overload("java.net.URL").implementation = function(url) { console.log("request url:"); console.log(url.toString()); return this.open(url); }});In this case, we hook into the popular OkHttp library and replace its okHttpClient. method. The rest should be self-explanatory.

Frida CodeShare

Frida has an official script repository where you can find handy utilities such as fridantiroot — a comprehensive script for disabling root detection, Universal Android SSL Pinning Bypass — an SSL pinning bypass, and Alert On MainActivity — a sample that renders a full Android dialog from JavaScript.

You can run any of these scripts without downloading them first, using the following command:

$ frida --codeshare dzonerzy/fridantiroot -U -f com.example.vulnapp

Cracking a CrackMe

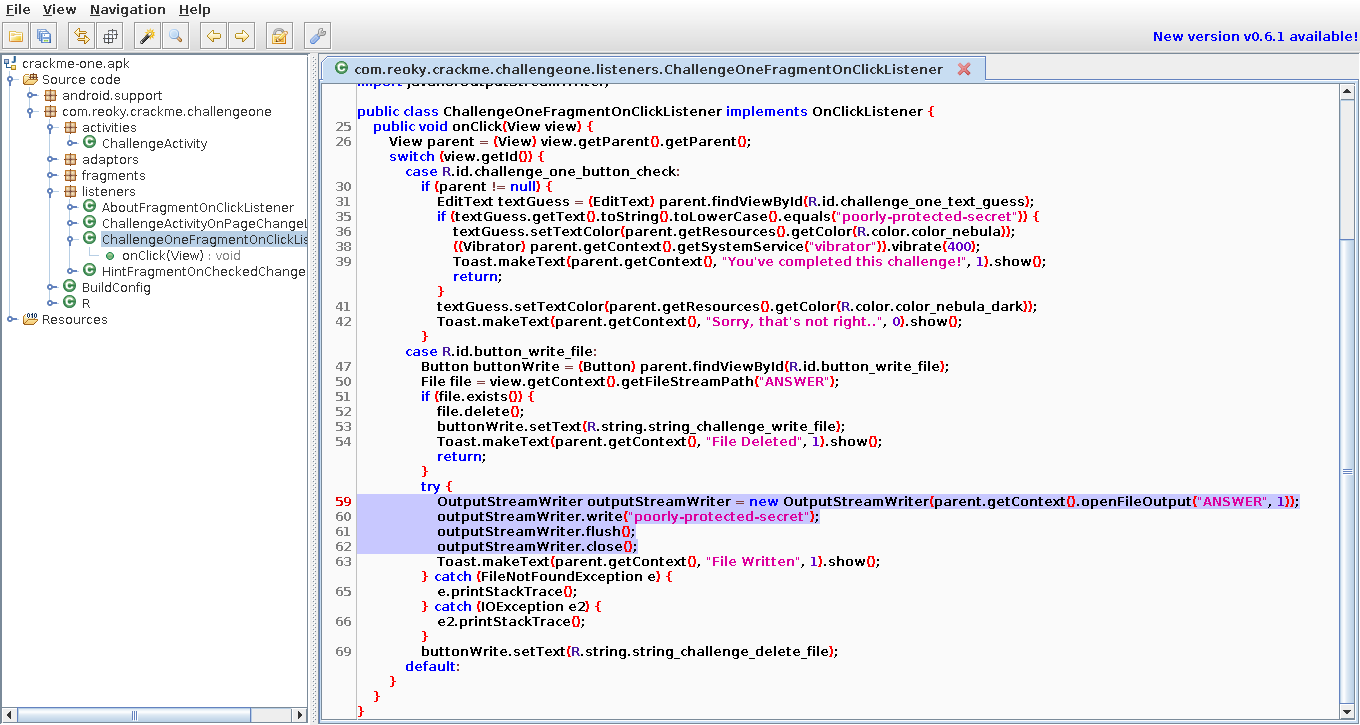

Now let’s try to hack something real. You can find plenty of different CrackMes out on the internet. We’ll take the first one we come across: this one—specifically, the first of the five posted in that repository. The crackme-one.apk app writes a file to its private directory, and our task is to extract the contents of that file. Up front: there are many ways to do this in twenty seconds, but it’s still a great example for learning how to work with Frida.

So, let’s download and install the app:

$ wget https://www.dropbox.com/s/mrjnme2xiv45j4g/crackme-one.apk

$ adb install crackme-one.apk

We’re offered a button to save a file or a prompt to enter an answer for validation. Obviously, to crack this CrackMe we need to intercept execution at the moment the file is written. But how? It’s actually straightforward. Most Android apps write data using either the java.io.OutputStream class or the java.io.OutputStreamWriter class. Each has a write() method that does the actual writing. All we need to do is hook that method with our own implementation and print the first argument, which will be either a byte array or a string.

Java.perform(function () { var os = Java.use("java.io.OutputStreamWriter"); os.write.overload('java.lang.String', 'int', 'int').implementation = function (string, off, len) { console.log(string) this.write(string, off, len); };});Run:

$ frida -U -f com.reoky.crackme.challengeone -l outputstream_write.js --no-pause

Voilà — a line appears on the screen.

poorly-protected-secret

Three points to note:

- This time we used the overload() method because OutputStreamWriter implements three write() overloads with different argument sets.

- We used the –no-pause option, which is needed if you want to do a cold start of the app but don’t want Frida to pause it right at launch.

- In fact, you could crack this CrackMe simply by going into its private directory and reading the file (that’s possible since our phone is rooted), or by decompiling the app (the text is in plain sight). There’s a catch, though: if the CrackMe stored the string encrypted and only decrypted it right before writing, decompilation wouldn’t help—at least not until you extracted the encryption key and wrote a script to decrypt it.

Conclusion

Frida is a very powerful tool that lets you do almost anything to a target app. But it’s not for everyone: you’ll need JavaScript skills and a solid grasp of how Android and its apps work. So if you’re just a script kiddie, you’ll have to settle for automated tools built on top of Frida, such as appmon.