It started when our malware lab received several samples of a password‑stealing trojan that differed in a few technical details but were clearly written by the same author. The trojan had the usual feature set for this kind of tool: locating and collecting saved passwords and browser cookies, copying text files, images, and documents from a predefined list, stealing credentials from FTP clients, and grabbing accounts for Telegram and the Steam client. It bundled everything it collected into an archive and uploaded it to cloud storage—Yandex.Disk in one build, and pCloud in later versions.

They say a good laugh adds years to your life. If that’s really true, then after going through the infostealer samples we received, malware analysts have probably earned themselves a few extra years.

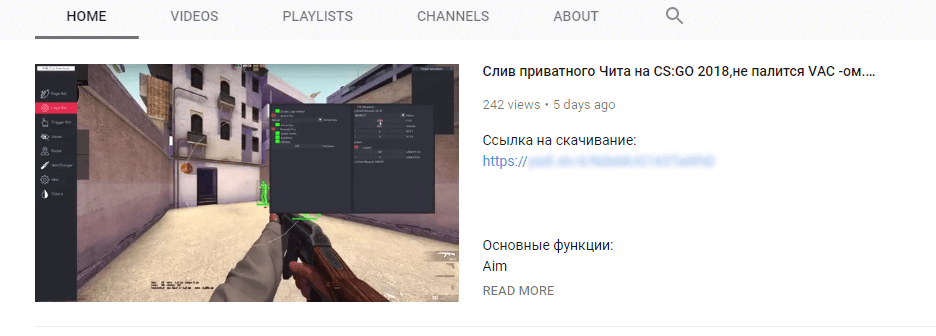

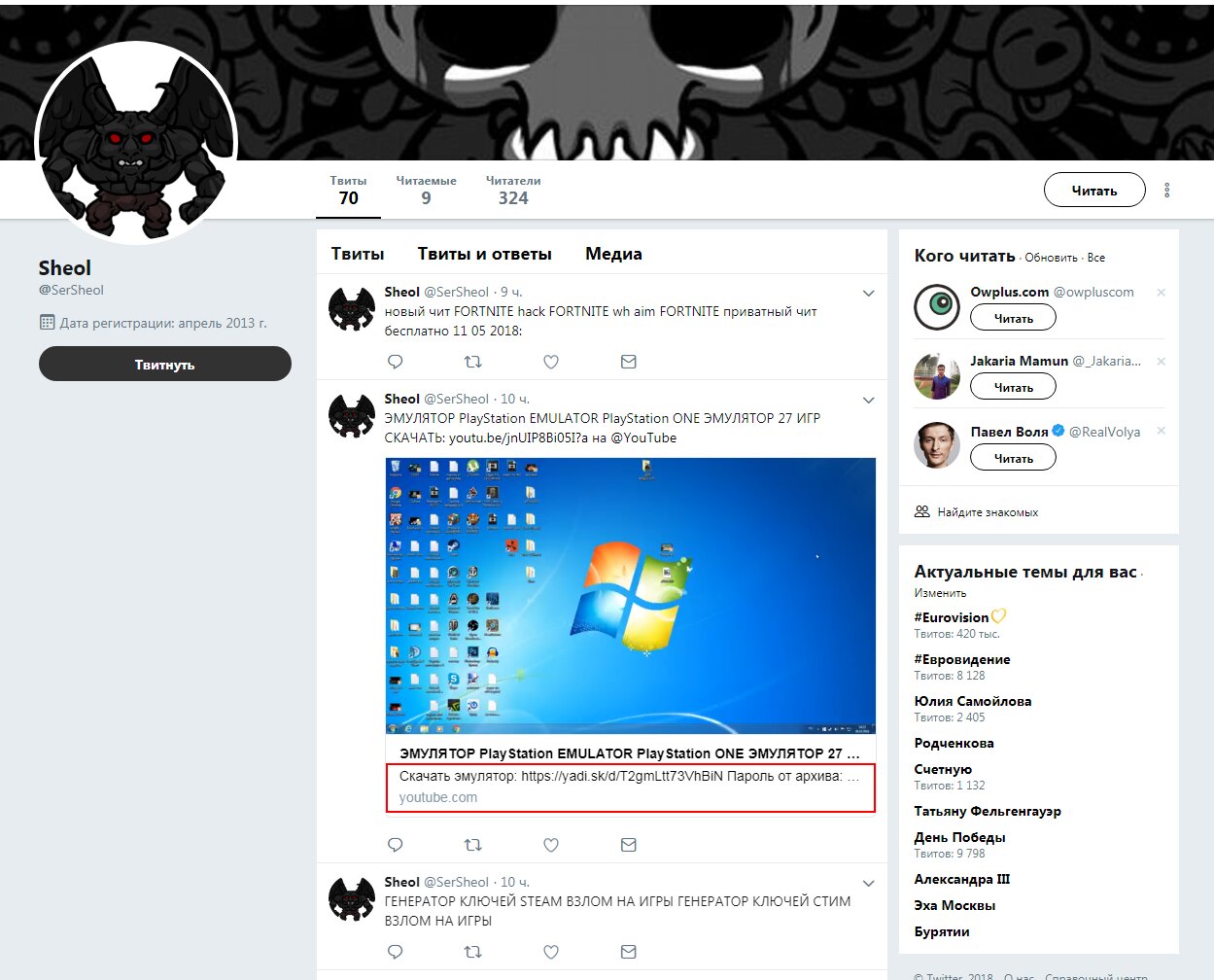

One early variant of the trojan was spread via YouTube through links in comments posted from several fake accounts. The videos focused on using cheats and trainers in popular games, and the links supposedly led to downloads for those tools. In other words, the campaign was clearly targeting cheat-seeking gamers, with one presumed objective being to hijack Steam accounts. Links to the malicious software were also aggressively promoted on Twitter.

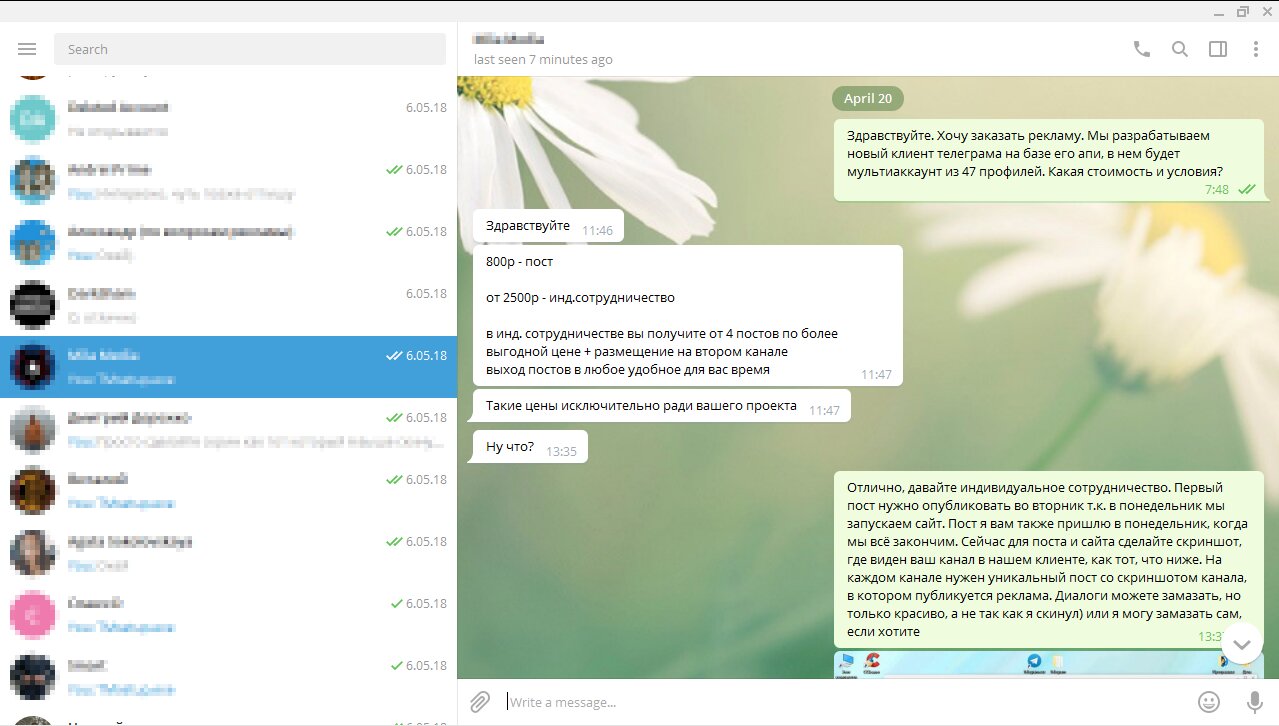

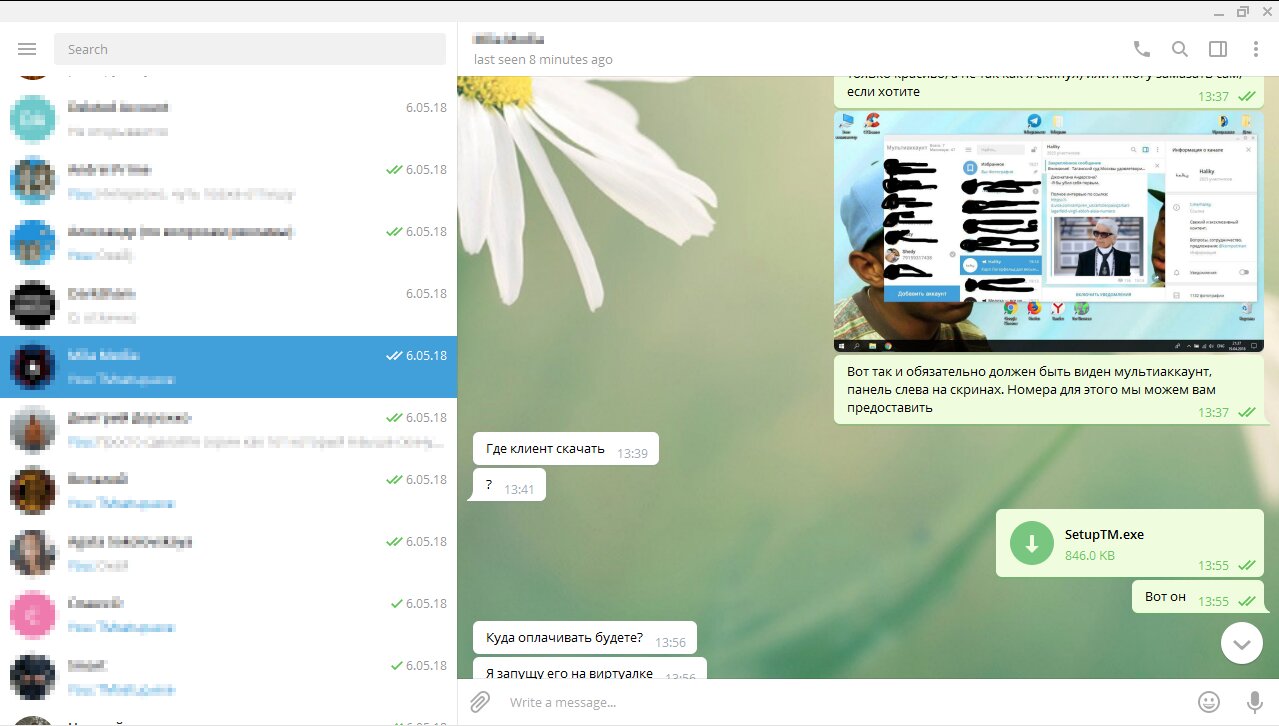

Another variant of the trojan was multi-component: in addition to the main spyware module, it included a scanner written in Go that located installed browsers on the system, and a separate utility that packaged stolen files into an archive and uploaded them to cloud storage. The trojan’s dropper was implemented in AutoIt, which in itself posed a special challenge for analysts. For distribution, the threat actors came up with a fairly original tactic: they contacted admins of popular Telegram channels and offered to promote a tool that lets you sign in to Telegram from multiple accounts at once. The app could be “tested” — targets were sent a link to an executable that secretly contained the trojan.

As for the stealers themselves, every single sample we examined was written in Python and packaged into an executable with py2exe. The trojan code was a mess—sloppy and downright inept. Take the Python function os., which returns a list of strings, each being a directory name. Normally you’d iterate over that list. Instead, for some reason the trojan’s author joined the list into a single space‑delimited string and then tried to find matches in it using a regular expression based on a predefined pattern.

steam = os.listdir(steampath)

steam = ' '.join(steam).decode('utf-8')

ssfnfiles = findall('(ssfn\\d+)', steam)

They say laughter adds years to your life. If that’s true, then after analyzing the stealer samples they received, malware analysts have probably gained a couple of extra years—because it’s impossible to look at this kind of “brilliant” code without bursting out laughing:

if score is 0:

pass

if score is not 0:

exit(1)

Apparently, the malware author hasn’t yet mastered the fiendishly complex construct if , or he’s just hilariously inept. The latter, as it turned out, was later fully confirmed.

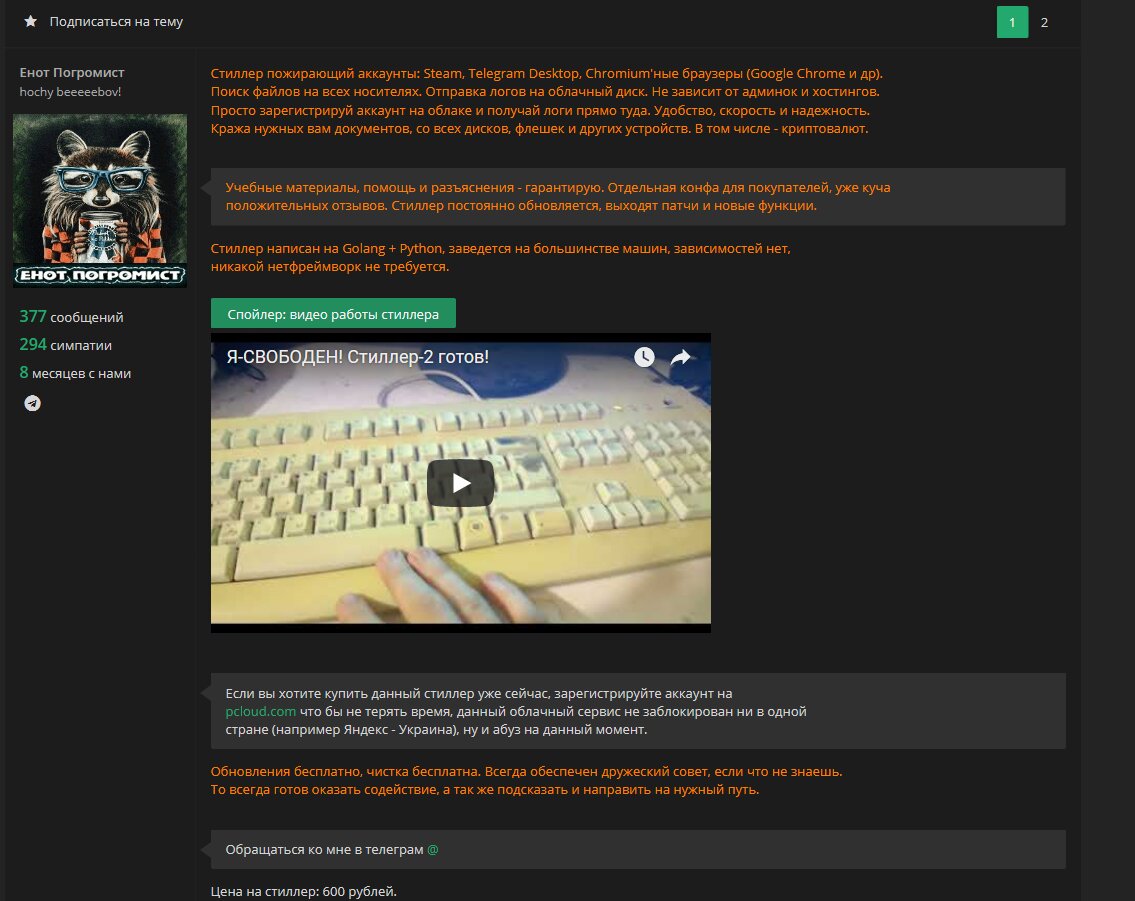

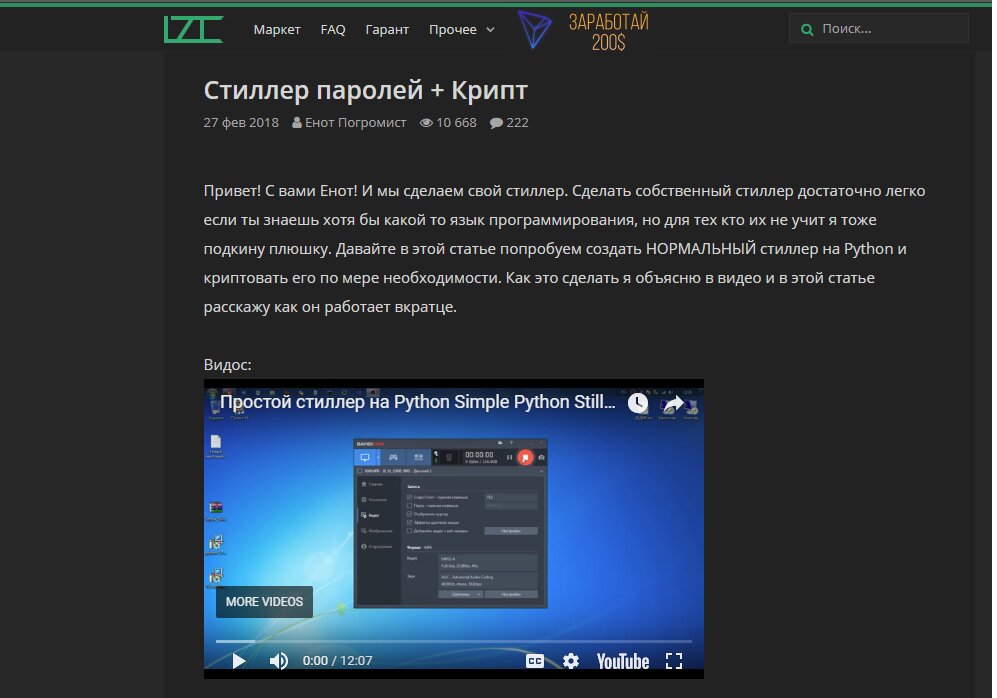

When a Python script is compiled, the interpreter embeds the original script name in the bytecode. The name we extracted from the executable was quite telling: enotproject. And the dropper written in AutoIt even preserved the path to the project files: \Users\User\Desktop\Racoon Stealer\build. A quick Google search for the keywords “Енот” and “Racoon Stealer” led us to a Lolzteam page where a user going by “Енот Погромист” (roughly, “Raccoon Coder”) is selling those very trojans and even offers workshops on writing Python-based stealers.

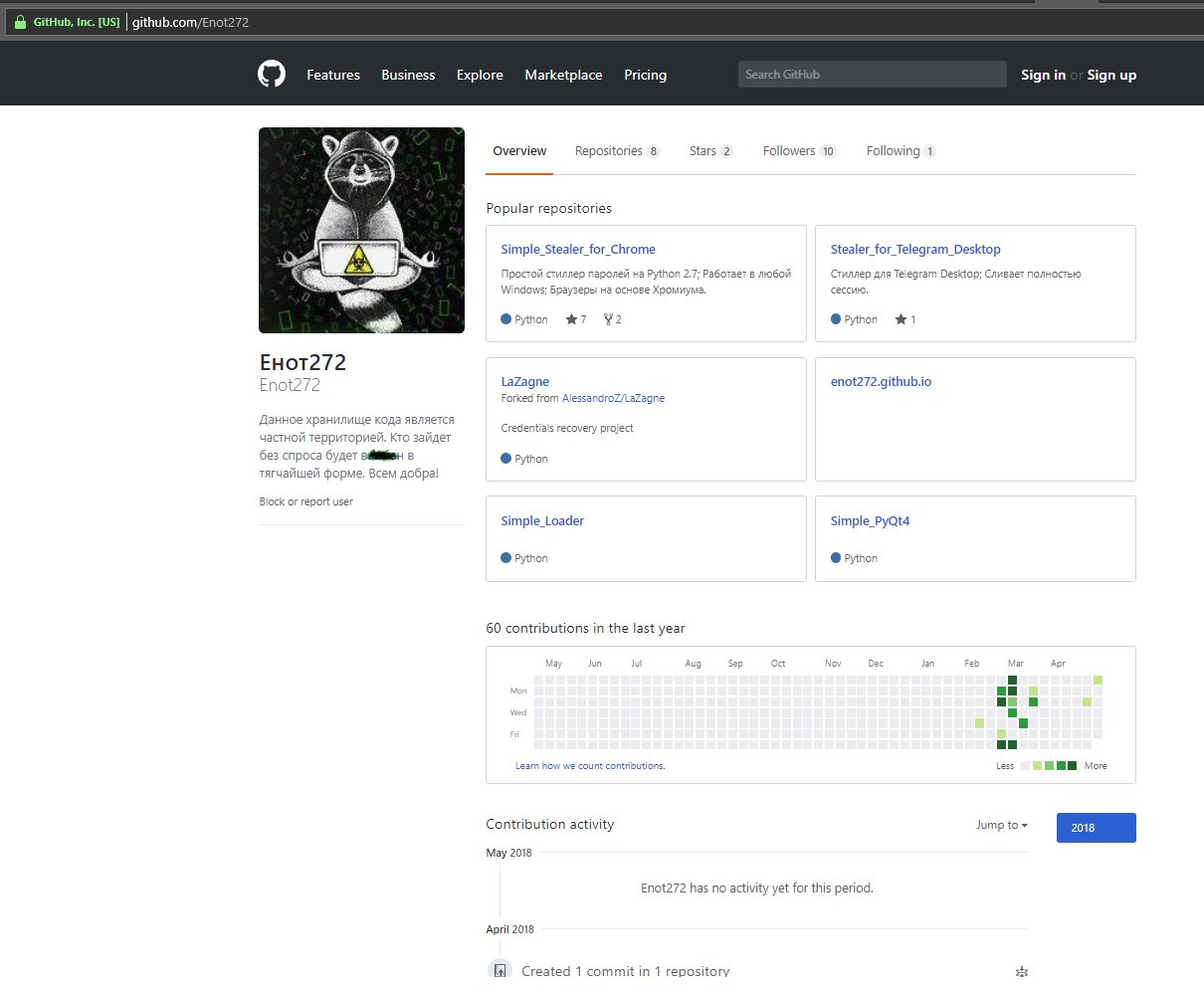

Our “Raccoon” turned out to be no ordinary creature: on top of everything else, he’s a video blogger who runs a channel about malware development, and he also maintains a GitHub account where he publishes his own custom Trojans as source code.

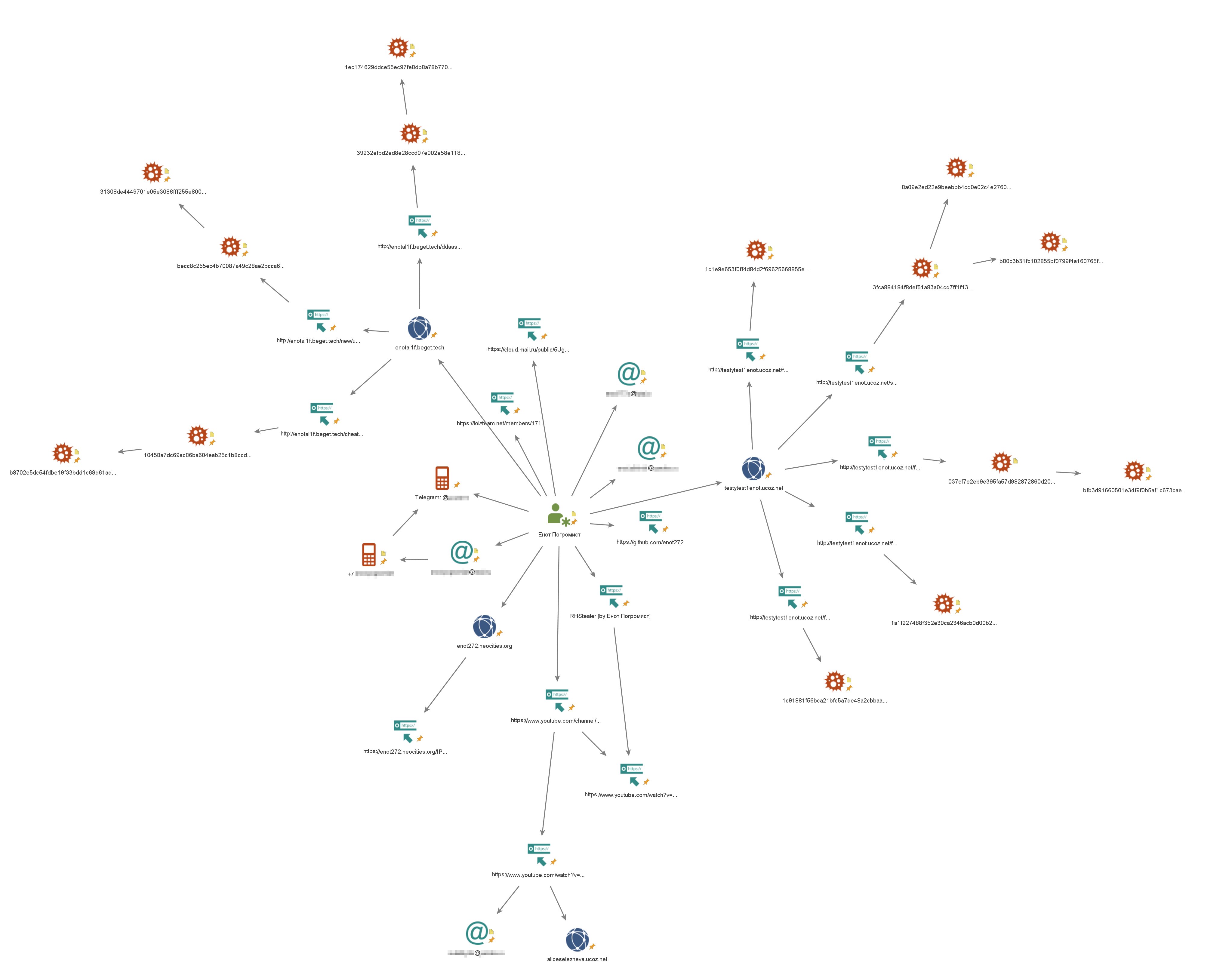

Because “Enot” left plenty of traces online—thanks to his videos and other publicly posted information—analysts quickly identified several infrastructure domains he used to distribute his malware, along with three personal email addresses. They also found the mobile phone number of “Enot Pogromist,” which was linked to a Telegram account he uses for contact. Taken together, the data on stealer samples, videos, domains, and email addresses yielded a relationship map of the malware author and the technical assets he employed.

But the real kicker was in the Trojan’s code. Customers who bought Enot’s stealers were told to register an account with the pCloud storage service, where the malware would automatically upload compressed archives of files from infected machines. Enot Pogromist then hardcoded each customer’s pCloud login and password directly into the stealer binaries, virtually in plaintext—making them trivial to extract.

And the buyers of these trojans were, of course, paragons of brilliance: many ran the stealer on their own machines (presumably for testing), which caused their personal files to be uploaded to a cloud repository that, courtesy of Raccoon, anyone could access. Some particularly inspired individuals even used their personal email addresses as the pCloud login—addresses tied to real social media profiles. And yes, they reused the same password everywhere.

Conclusion

It’s amazing how much personal information people voluntarily leave online.

Since “Enot Pogromist” was kind enough to leak private information about his clients, it would’ve been silly not to look into what they do when they’re not out buying Trojans. Turns out many of them also use other infostealers, which are plentiful on the usual forums. The data we uncovered led us to various online resources: one after another we found personal social media pages, YouTube channels, email addresses, mobile numbers, e‑wallet IDs in payment systems… Some of Enot’s clients own websites — WHOIS lookups revealed the names of the administrators for their domains. One “fearsome hacker” even turned out to have a school e‑diary — the kind all students use these days.

As a result, we quickly identified and de-anonymized every Raccoon Stealer customer, compiled a detailed dossier on each one, and filed everything neatly. Sometimes raccoons turn out to be very handy in the fight against cybercrime.

In short, to trace a malware author, sometimes all it takes is careful attention to small details—and that alone can lead to a major, successful investigation.