Game Engines

In my articles on choosing a game engine (“Review of the Most Popular Engines for Game Development” and “Comparing the Six Best Game Engines”), I mostly covered the usual suspects: Torque 2D/3D, Unity 3D, Unreal Engine 4, and CryEngine. There’s not much mystery there, and little has changed over the past year. In this piece, we’ll look at what didn’t make it into those earlier write-ups—interesting but less widely used options.

TheGameCreators has been proudly building game development tools since 1999. And even though many tools from other vendors are free, TGC sells its products and clearly turns a profit. Their portfolio includes projects like DarkBASIC, DarkGDK (I once wrote an entire series of articles about this engine a long time ago), and FPS Creator. These products have since been open-sourced and are hosted on GitHub. DarkGDK has always been a C++ library. Today, the company is actively developing three products: MyWorld (for creating RPGs), GameGuru (for building 3D shooters without programming), and AppGameKit.

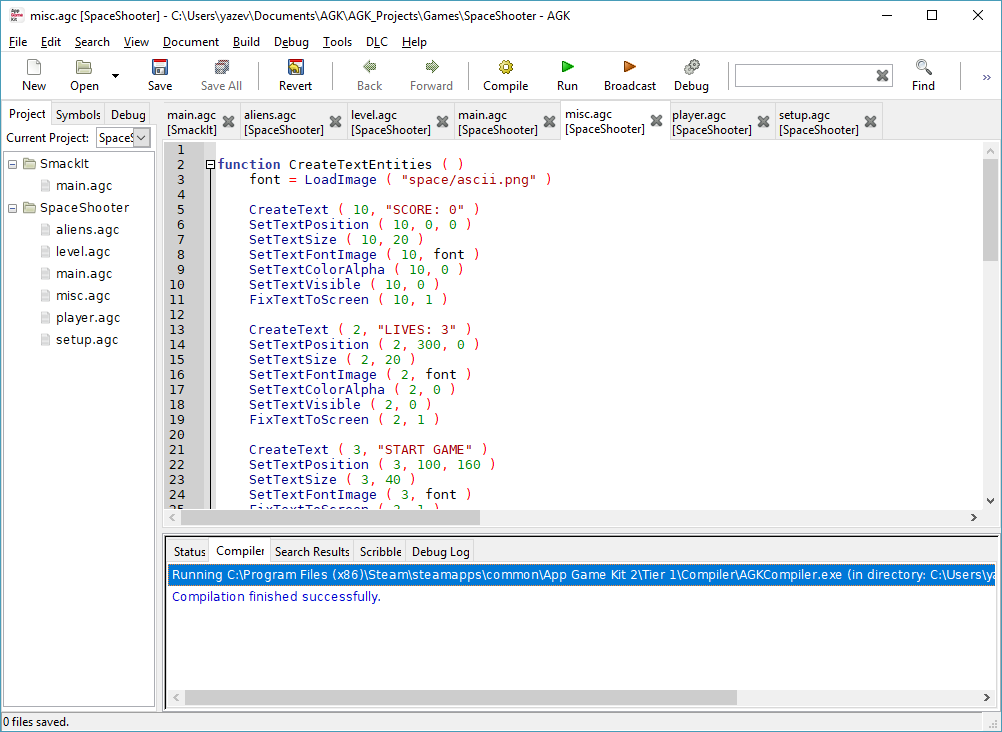

AGK is TGC’s flagship product, a universal engine for building games of any genre across all major platforms: Windows, Linux, macOS, Android, iOS, HTML5, and even Raspberry Pi (the module is a separate download). And it all comes from a single codebase! That may not amaze anyone these days, but it’s still nice. With AGK you can create not only 2D and 3D games, but also regular applications.

AGK consists of two tiers. Tier 1 is game development using a versatile scripting language (an easy-to-learn BASIC tailored for games). Tier 2 is a framework you can link to from C++. In other words, AppGameKit is a blend of the company’s modernized, improved legacy products—DarkBASIC and DarkGDK—in a single package.

Regardless of which tier you use for development, in both cases you can build the game for all supported platforms. In Tier 1 you write code in the dedicated IDE for AGK’s scripting language; in Tier 2 you use your favorite C++ environment, such as Visual Studio.

In addition, AGK supports easy integration with PHP for developing online games and applications. Key features available to AGK-built games include support for the Box2D and Bullet (3D) physics engines (for 2D and 3D graphics, respectively), particle systems, video playback, ad display, camera support, and various social integrations.

AGK is great for prototyping and putting new mechanics through their paces, and it’s perfectly suitable for building complete products as well. If you decide to buy it, I recommend getting it on Steam rather than from the official website, since the price is noticeably better.

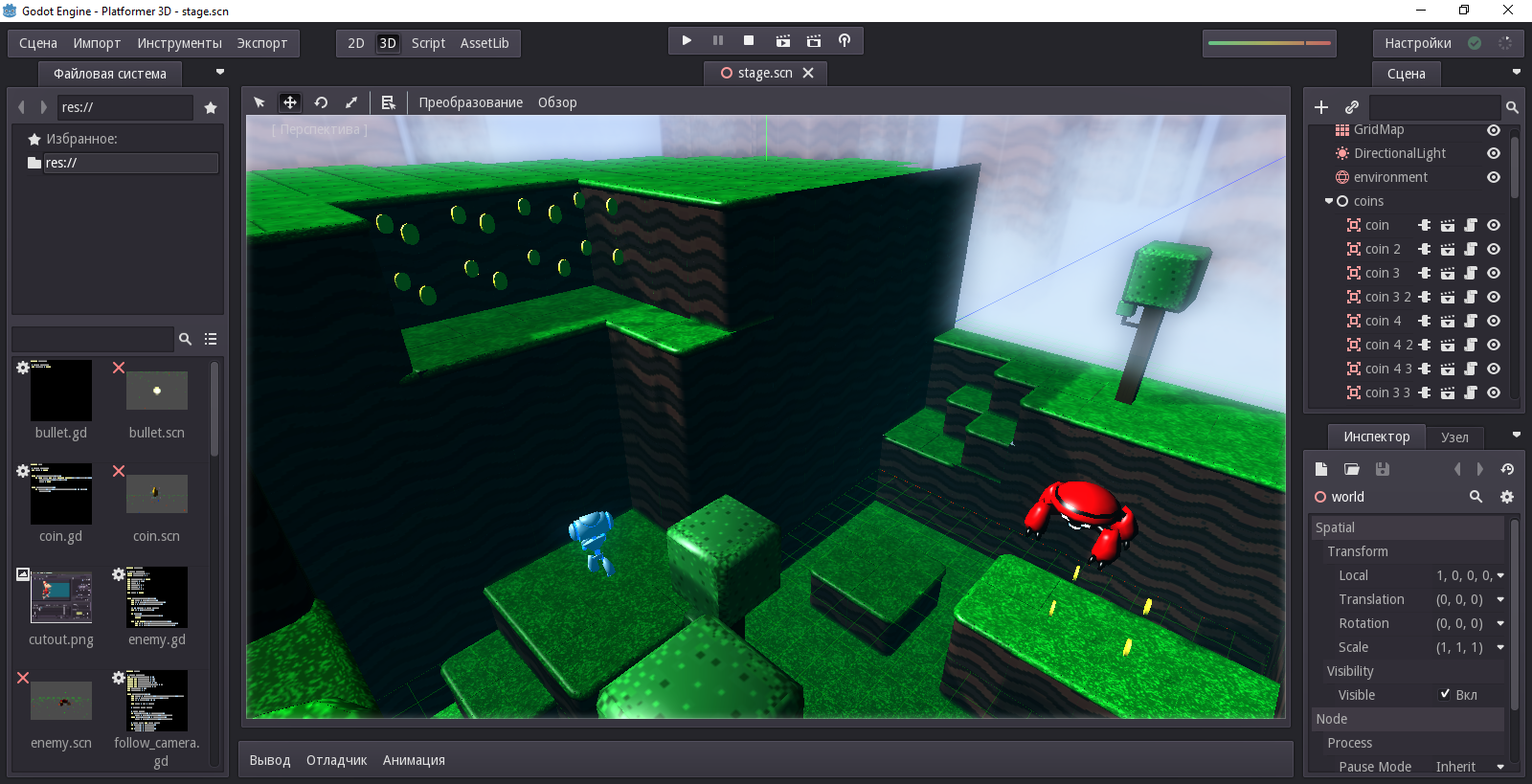

Another engine I want to highlight is Godot. It’s recently caught my attention, and here’s why. It’s completely open source and cross‑platform. You can develop on Windows, Linux, or macOS, and ship to Windows Desktop, Windows Universal, Linux, macOS, BSD, Haiku, Android, iOS, BlackBerry 10, and HTML5. Godot was started by developers at the Argentine studio Okam in 2007. It was originally built for the company’s own projects, but once it matured, the authors decided to publish it on GitHub in 2014. Since then, the community has been actively contributing to its development.

From the outset, the engine was designed as a complete game development environment that doesn’t require external coding tools. It includes a custom interface, its own GDScript language, the full C++ source code, and a wide range of object types used in game creation. Some are for building user interfaces, others provide sprites for 2D games, others let you create physics bodies, still others handle audio and video, some add configurable particle systems, others enable animated 3D objects, and yet others let you assemble entire scenes, and more.

The scripting language is reminiscent of Python but improves on it in some respects, such as support for static typing. Godot’s built‑in code editor has everything you’d expect from a modern IDE: syntax highlighting, code completion, auto-indentation, and more. Notable extras include a debugger, a profiler, and a VRAM monitor.

Godot’s graphics stack is based on OpenGL ES 2.0. It includes a visual shader editor and its own shading language. Godot also has a built-in animation editor for both characters and other objects. To meet performance goals, the Godot developers avoided third-party physics engines and built their own physics solution from scratch.

To build for multiple platforms, just download the exporter and use it to create a bundle for the target platform. You won’t need to modify the original project.

How Are Indie Developers Doing?

A lot has happened on the indie scene over the past year. As I anticipated, indies trying to compete with “big” developers backed by publishers have started moving into 3D and large-scale online. Most of these are session-based online shooters, though you occasionally see an MMO. This shift has been enabled by modern game tech, especially engines. Meanwhile, many indies (the majority, in fact) are still making 2D action games and adventures for mobile and PC. And in going toe-to-toe with AAA titles, indies sometimes manage to deliver games that outclass big-budget rivals in design, storytelling, stylistic depth, and visual polish.

Graphics Editors

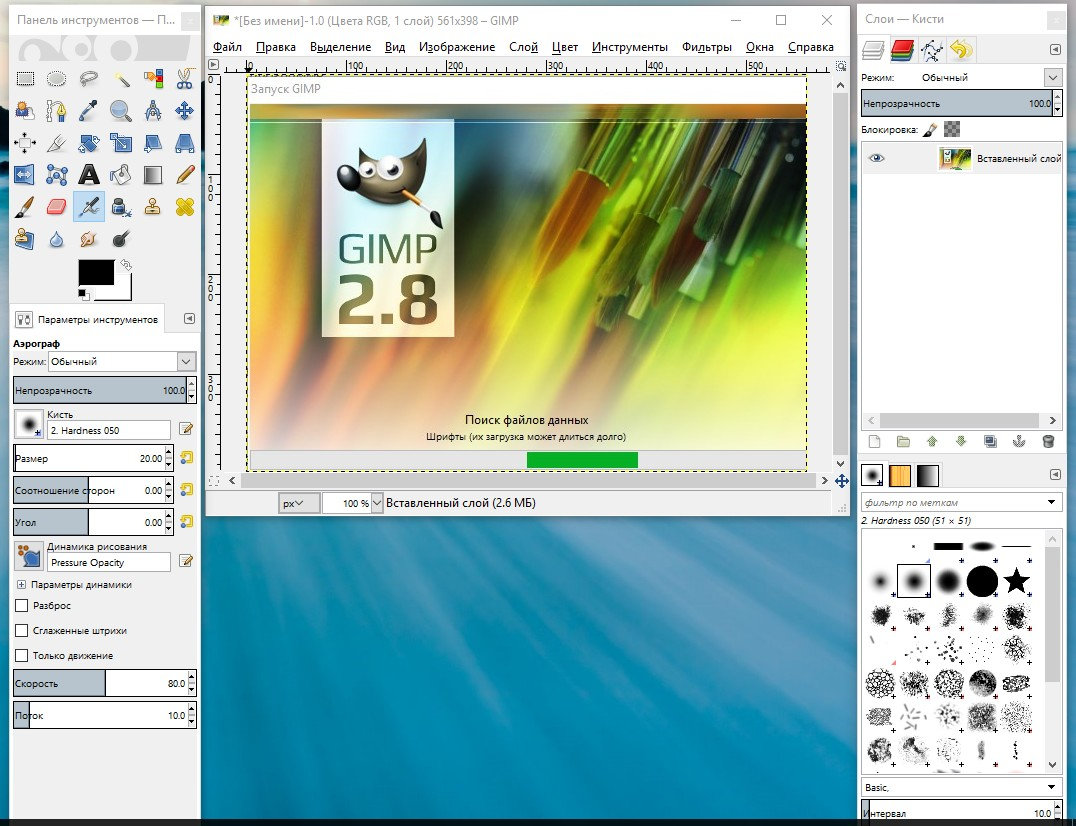

Graphic editors are among the essential tools for developing any game—you simply can’t do without them. And it doesn’t matter whether you’re building a 2D or a 3D game: you’ll need 2D editors either way.

Honestly, I don’t like Photoshop and haven’t used it in years. Among proprietary editors, I prefer the CorelDRAW suite. It includes an excellent vector editor—CorelDRAW—and Corel Photo-Paint, which is on par with Photoshop in terms of features. I have the impression CorelDRAW outperforms Adobe Illustrator, though I haven’t really used the latter. The downside is that CorelDRAW costs a small fortune. So when I went legit as an indie, I dropped it and, in one go, lost both my vector and raster editors.

That said, the open-source world is full of compelling graphics editors. There are clear leaders that have been actively developed for many years, and feature-wise they rival proprietary solutions. My top choice among raster editors is GIMP. It’s been in development since 1995 and includes all the core tools and the vast majority of Photoshop’s options and settings.

Among vector editors, the obvious choice is Inkscape. Inkscape looks and works much like CorelDRAW, with a broadly similar toolset.

Drawing and fill tools, a large library of ready-made shapes, shape editing, and more. It has layers, filters, and extensions. In short, everything you need to be productive.

3D Modeling Software

Maya, LightWave, 3ds Max, ZBrush are excellent 3D modeling and animation tools, but they’re unfortunately too expensive for indie developers. What can open source offer in this space?

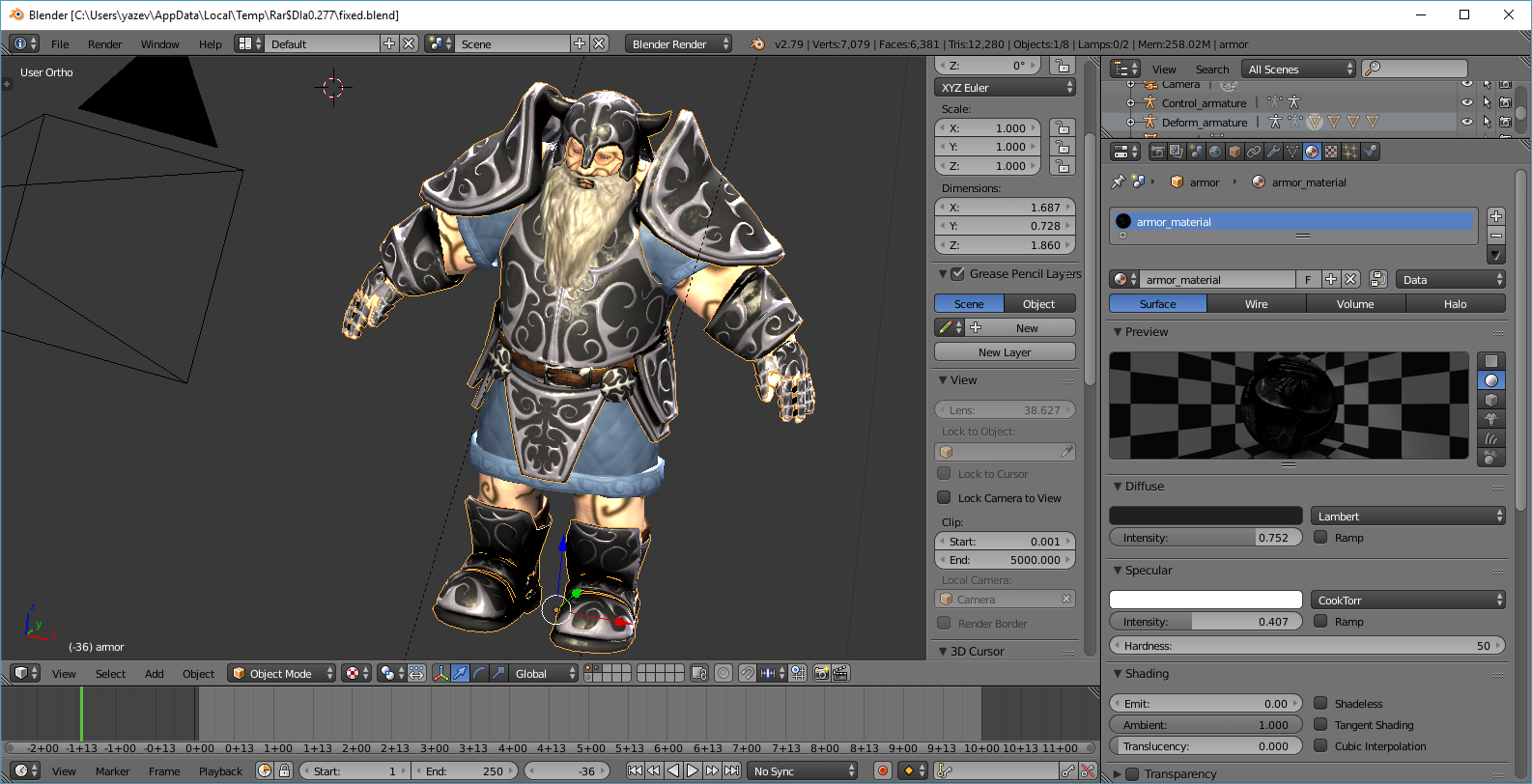

The most popular open-source 3D modeling tool is undoubtedly Blender. It first appeared in 1994 and spent its early years as a commercial product (you might laugh, but we at Hacker magazine were recommending it back in the early 2000s — Ed.). In 2002 its source code was released under a free license, and it has been under active development ever since.

Blender has always had a reputation for being complex. Part of the reason was its early versions, where most commands were triggered via keyboard shortcuts. Things have improved a lot since then, and now you can invoke almost any command either from a toolbar button or a menu.

In addition to modeling tools (polygonal and sculpting, Bézier curves, NURBS, metaballs), Blender offers rendering engines, animation tools (inverse kinematics, skeletal, and non-linear animation), video creation and editing, physics (soft- and rigid-body dynamics powered by the Bullet physics engine), and a hair system.

Blender also includes the Blender Game Engine, which lets you build simple game logic, handle collisions, and define reactions. Game logic is written in Python. You can also use it to extend the set of tools bundled with Blender.

Besides Blender, there’s another free (though not open-source) option—TrueSpace.

Up until 2008, this program was developed by Caligari Corporation. Microsoft then acquired the rights, and in 2010 development was discontinued, with the final version (7.61) released for free. Its roots go back to 1986, when it was developed for Amiga computers. The first Windows release of TrueSpace didn’t arrive until 1994.

Microsoft used the technologies behind TrueSpace in its 3D Builder app (available for free in the Windows Store).

The application lets you scan, import from a wide range of file formats, edit, construct 3D objects, and 3D print models.

About ten years ago, when I was heavily into 3D modeling and animation, I was really fond of this program for its cool interface that didn’t look or feel like any other modeler.

3D Characters

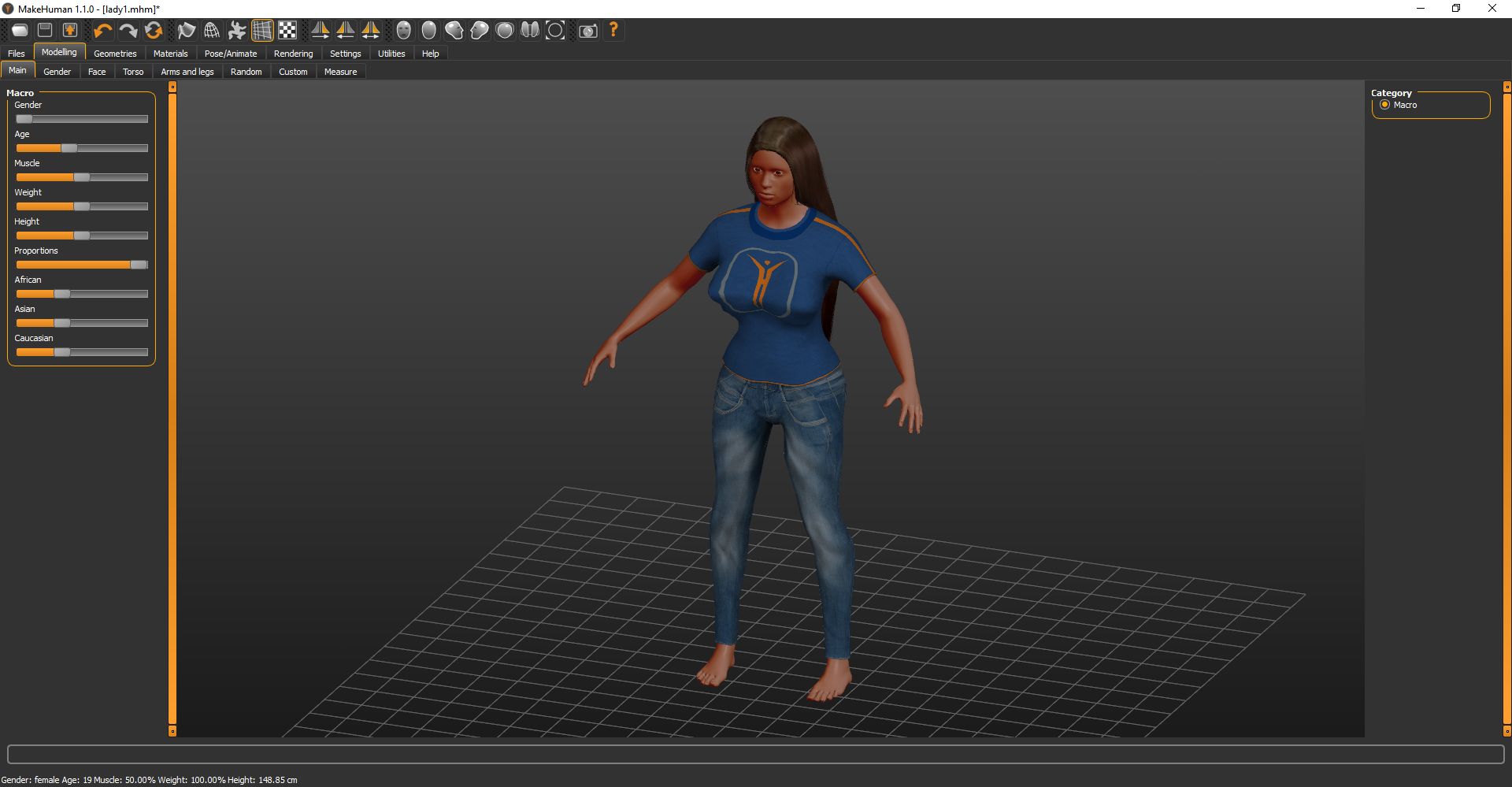

For quickly creating humanoid 3D characters, you can use the open-source MakeHuman. Character creation starts by configuring the base model (the default character). Parameters include gender, age, height, weight, musculature, pose, and more. The app is somewhat reminiscent of Blender but offers a simpler, more user-friendly interface.

The current version 1.1.0 is developed in C++ and Python. Graphics are handled and rendered via OpenGL. Back in 1999, when the app first appeared, it was a Blender plugin called MakeHead. Later, after running into the limits of the Python API, the team decided to restart the project in C. It was later moved to C++. As development and maintenance became increasingly difficult, in 2009 the developers chose to return to Python with a C++ core and spin it off as a project independent of Blender. As a result, the first stable release of MakeHuman came out in 2014.

I cover working with 3D characters in more detail, along with another useful app (Fuse), in an article on my website.

Creating Custom Fonts

Since many fonts aren’t free and are protected by copyright, we need to use our own fonts. There are a number of tools for creating them—both commercial and open-source.

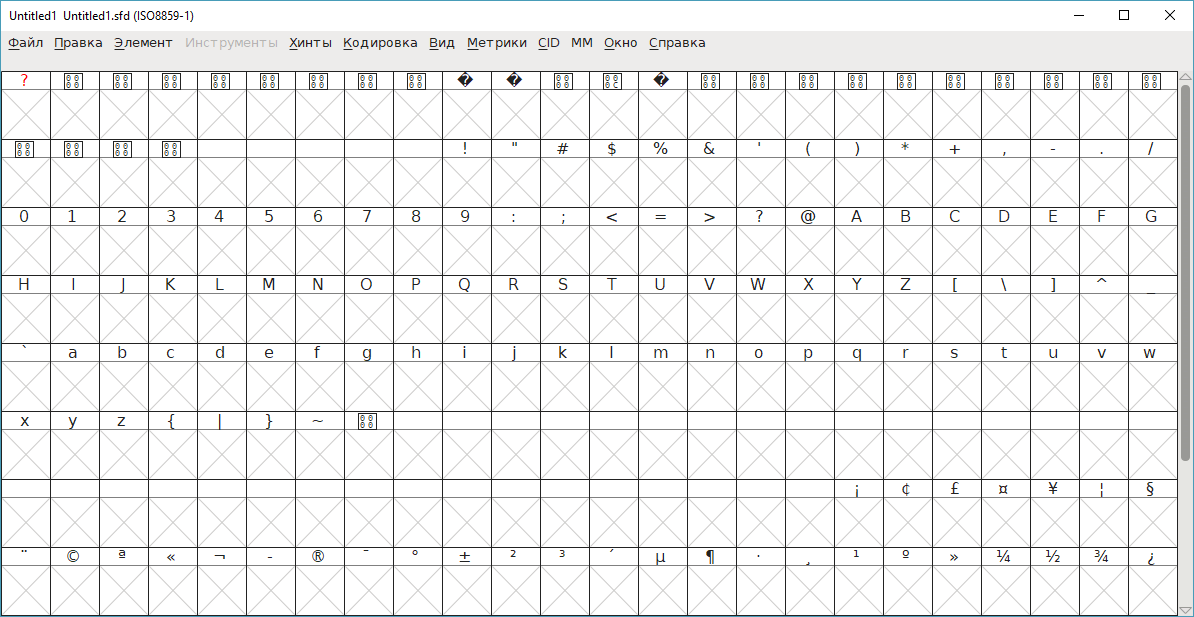

Of the latter, two tools are worth highlighting. The first is FontForge. It’s a full-featured tool for editing existing fonts and creating new ones in the TrueType, PostScript, and OpenType formats. FontForge was originally a Linux application, so it’s built on GTK+ and runs on Windows via Cygwin.

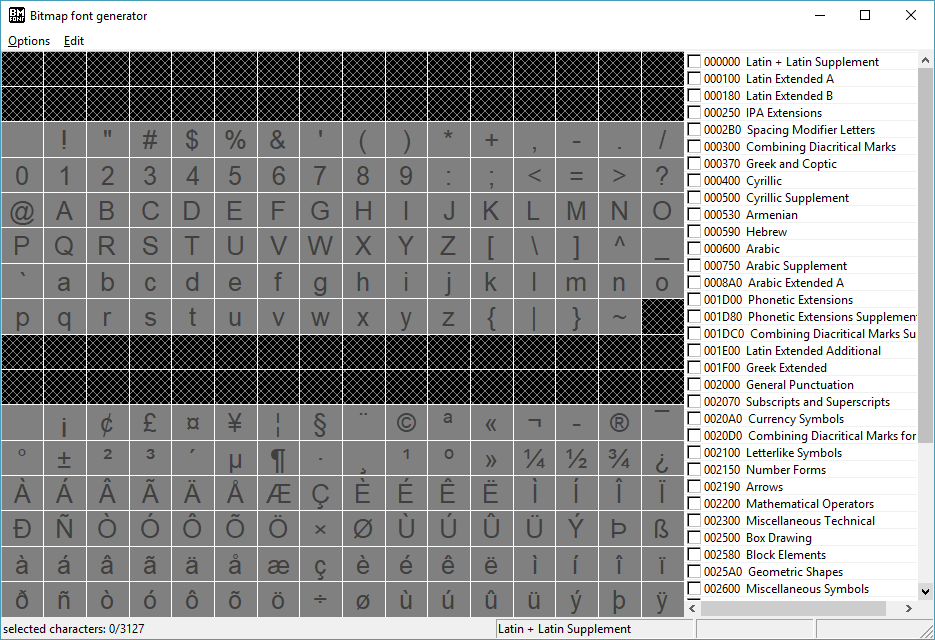

Another handy tool is BMFont. It converts any system-installed font into a compact bitmap atlas that’s easy to load in a game. The program can even save, in a separate file, the coordinates of every glyph along with spacing/kerning metrics. In short, BMFont is an invaluable tool in a game developer’s toolkit.

Level Design

In a 2D game, the map is essentially a background plus elements that characters and NPCs can interact with. You can build all of this by hand: draw the background and the elements separately, then assemble them in the game, creating a separate object in the engine for each individual element.

But there’s a better way—use a tile map editor. Tile-based (or tiled) graphics are used to build game levels by filling large areas with pre-made tiles. If you lay them out properly and add some variation, the player won’t notice any repetition.

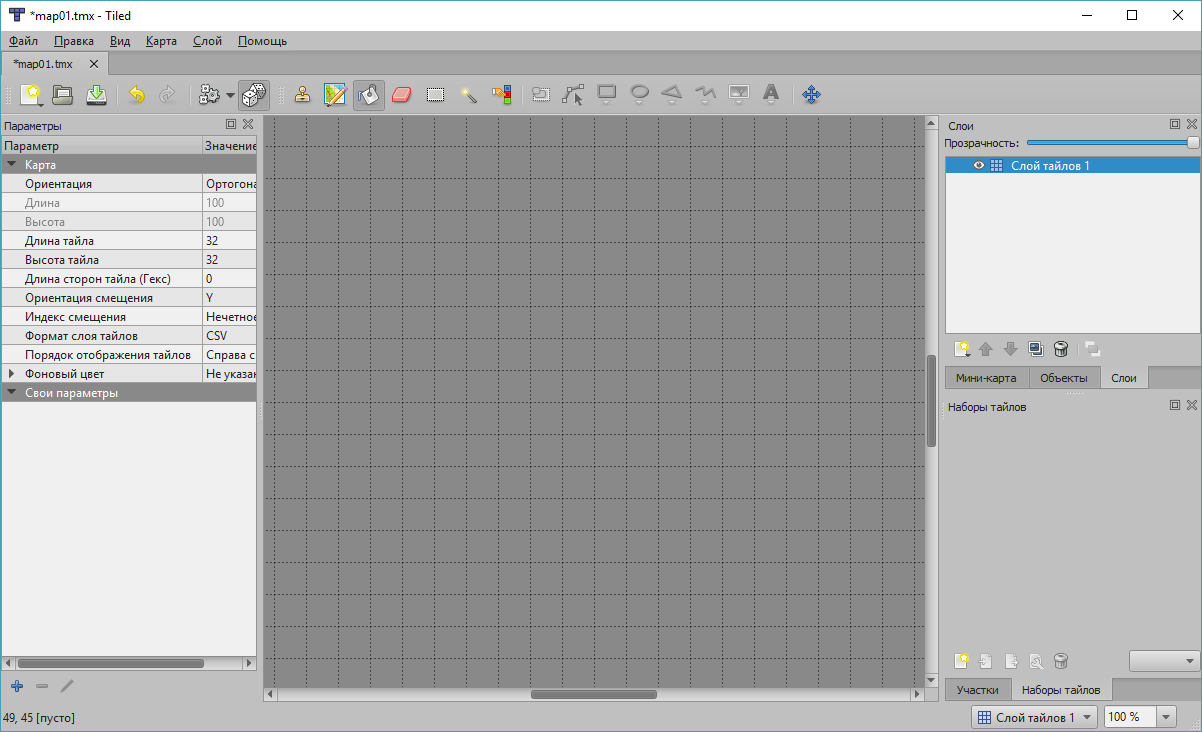

One of the most widely used tile map editors is the free, open-source program Tiled. It lets you build maps for both 2D and isometric games—think side-scrolling or top-down platformers, RPGs, and strategy games. Tiles can be square rasters or hexagons, and you can use any image as a tile.

Maps in Tiled are organized into layers. You can define collision properties for specific tiles. Levels you create are saved in the TMX XML format, which you can then load into your game engine. TMX is supported by a number of engines. Besides the XML-based format, there’s also a JSON-based option.

Creating Texture Atlases

Creating a separate file for every image is a bad idea. A game can use dozens or even hundreds of images, and loading each one individually is impractical—especially for animation. That’s why animation typically uses sprite sheets, each packing a large number of images.

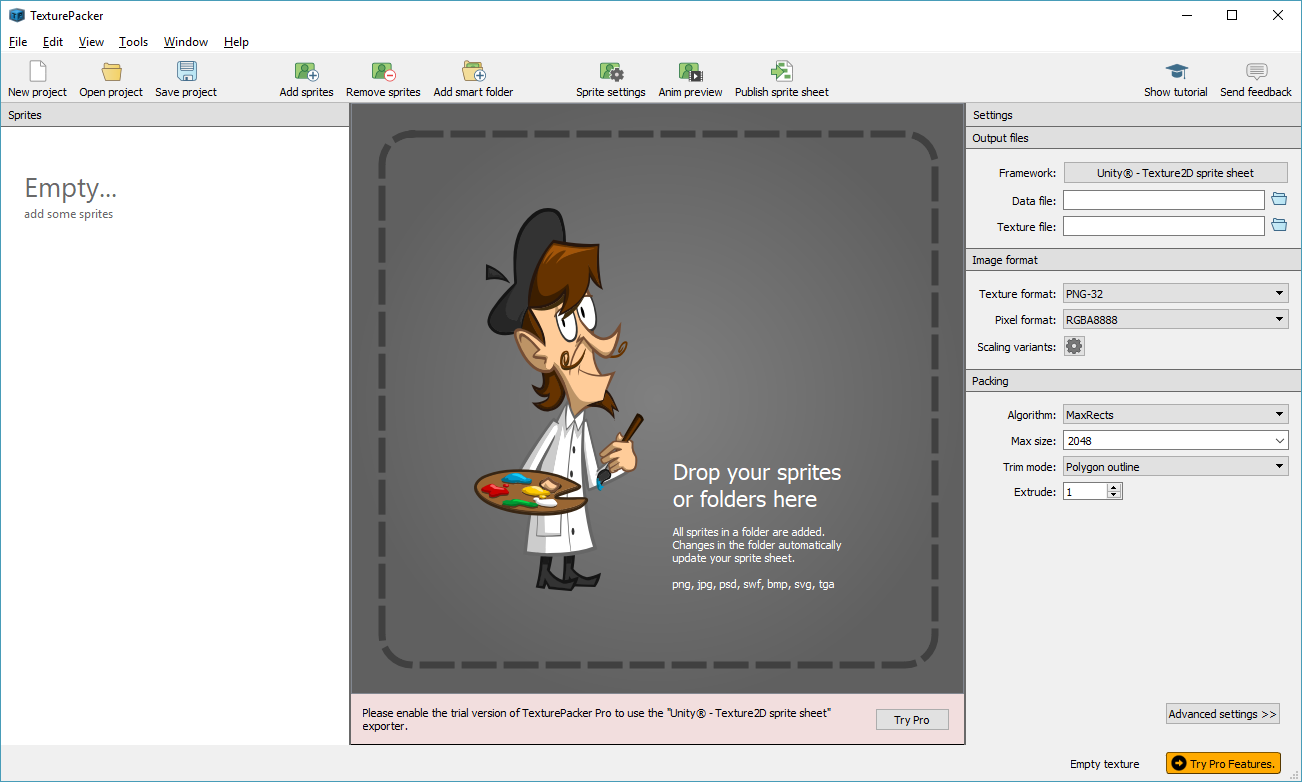

To create sprite sheets, you can use TexturePacker. On first launch, you’ll choose between the Free and Pro editions. Pro adds features like SWF export, a command-line interface, and automation tools. The Free edition includes only the GUI. The full TexturePacker supports sprite-sheet formats for around thirty game engines (including Unity 3D and Cocos2d-x), while the Free edition is more limited; you can compare the lists on the developer’s website.

TexturePacker not only builds a compact sprite sheet, it also compresses the sprites and lets you optimize color, saving even more resources. When you launch the free version, it asks which game framework (or engine) you’re targeting for the sprite sheet. After that, you’ll be prompted to load your images.

Creating Animations

Animated sprites are used constantly in games. You could draw every frame of an object’s animation by hand in a graphics editor, but that’s slow and inefficient. It’s much better to use dedicated tools.

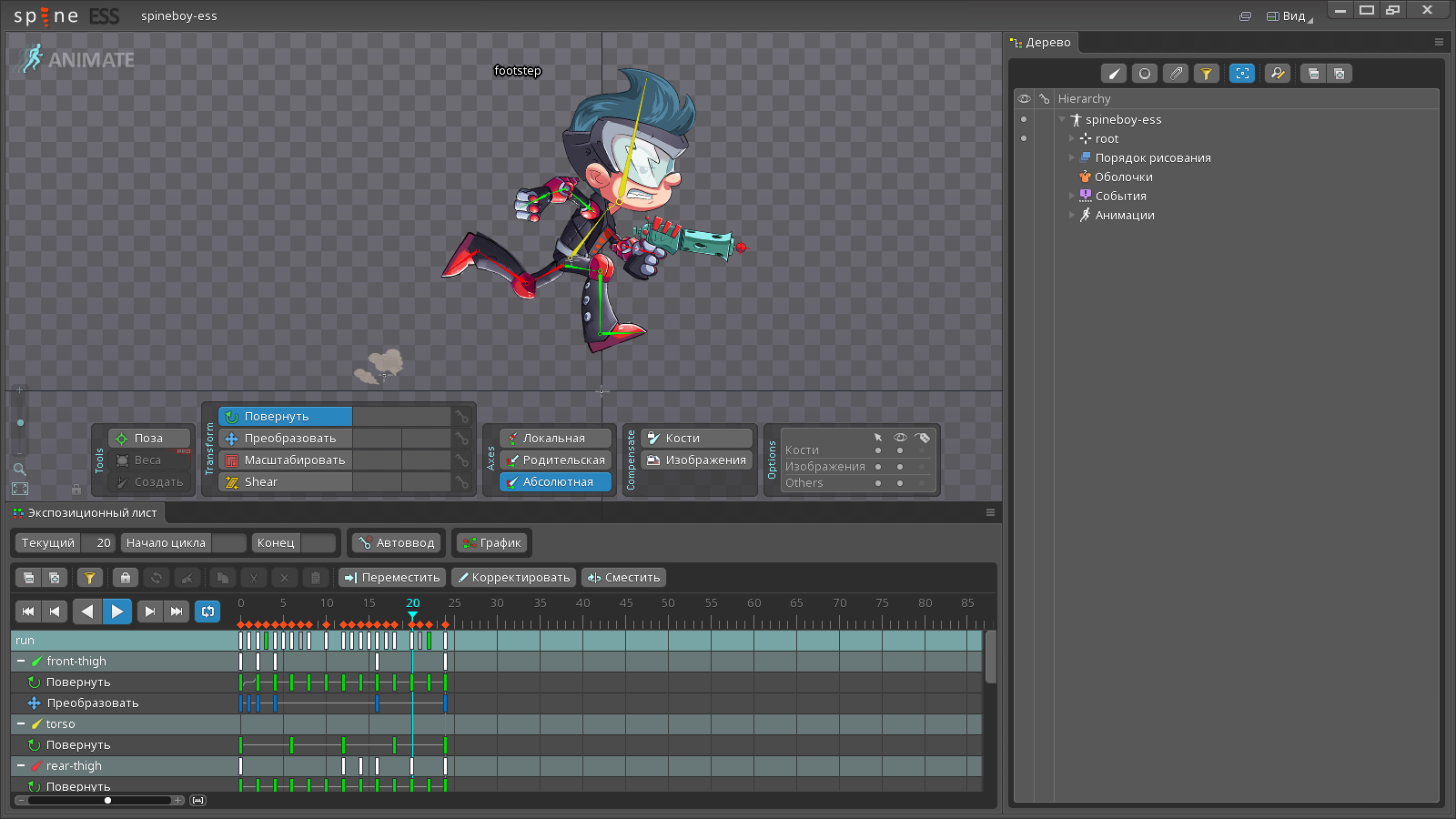

You can animate a 2D object with something like the Flash editor, but I much prefer Spine from Esoteric Software. It isn’t free, but a tool as powerful as Spine is worth the price (300 for the Professional one). Spine creates skeletal animations from related graphic assets, and skeletal animation works great not only for characters but also for the motion and interaction of all kinds of other objects. Spine can export your animations in various formats, both as video and as individual frames.

Before buying this tool, you can try the trial version. It differs from the full version in that saving projects and exporting data are disabled.

In Spine, you attach images to bones and animate the bones. What advantages does skeletal animation offer over traditional frame-by-frame animation?

- Smaller final data size by using fewer images—only bone coordinates are stored.

- Less to render as a result.

- Interpolation makes the animation run faster and look smoother.

- Skeletal animations can be blended.

- Animation can be controlled programmatically.

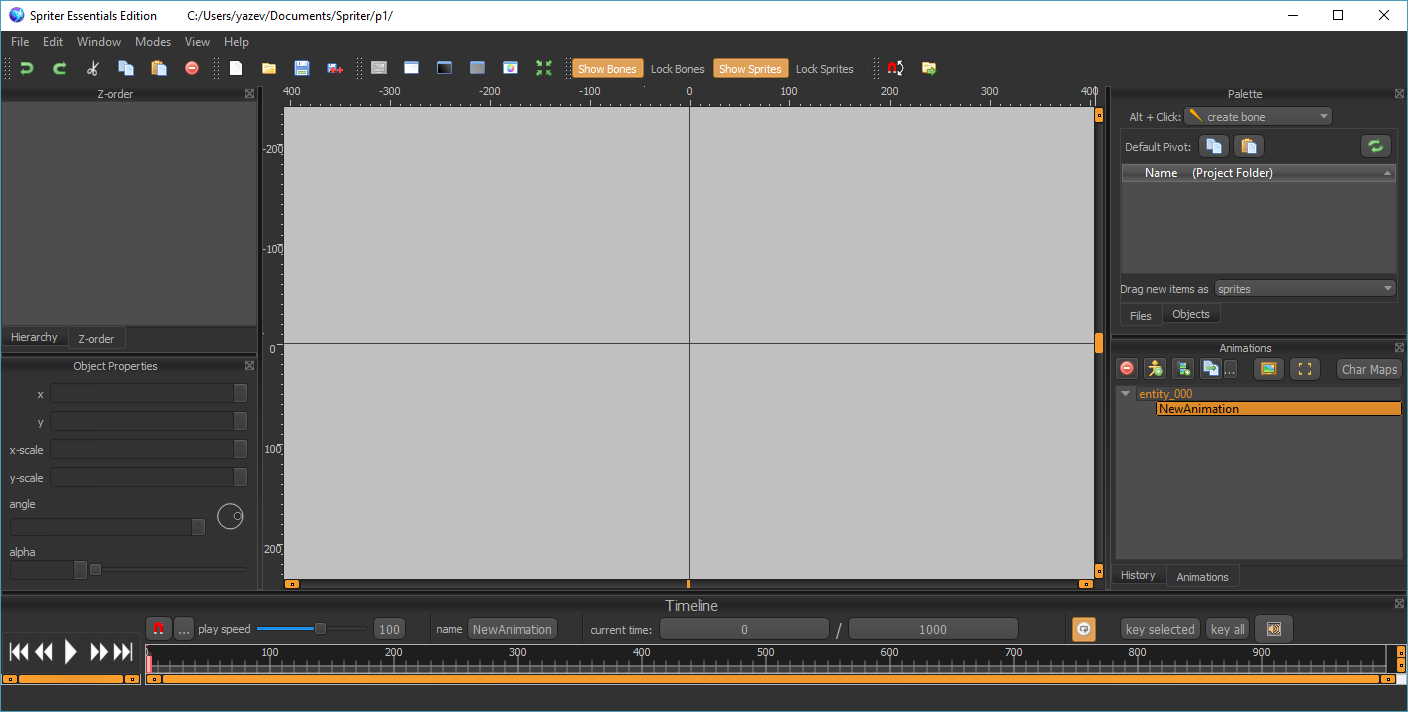

Another very useful tool for creating sprite animations is Spriter. It’s broadly similar to Spine and offers the same functionality. Spriter comes in both demo and professional editions.

Sound Design

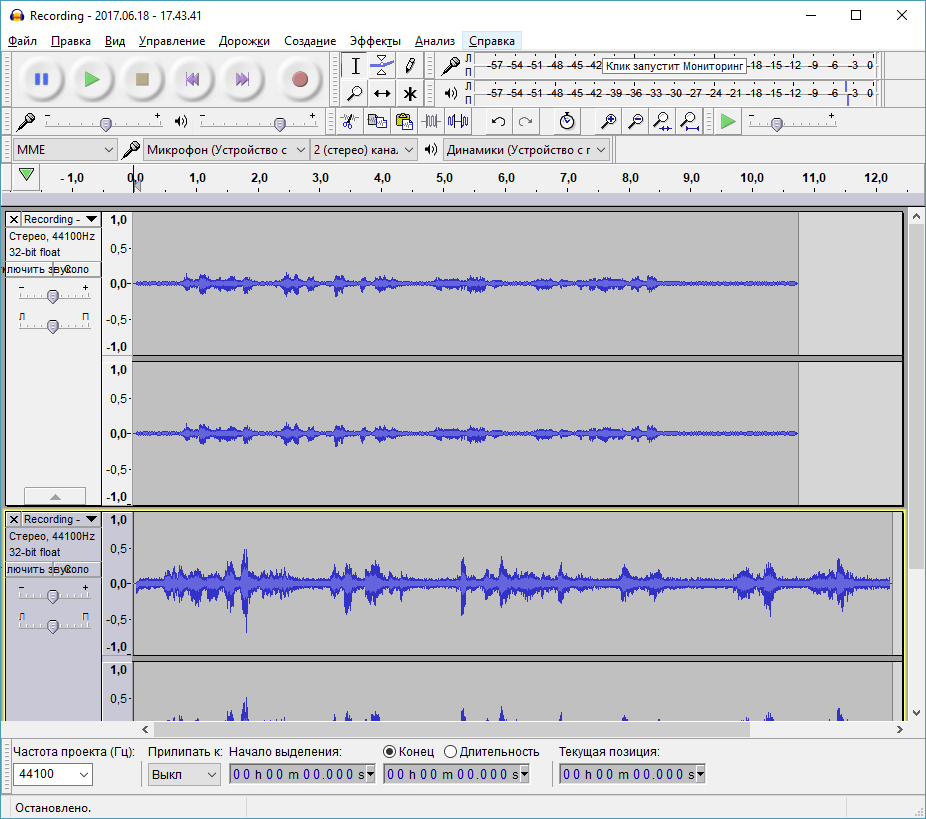

A sound designer in the game industry has a highly creative job. They obtain the sounds they need in various ways: popping balloons, setting off firecrackers, pouring water from one glass to another, recording the sound of rain from a rooftop—and then processing all of these in an audio editor. Or they might create them from scratch. There are many commercial editors on the market, and plenty of free ones as well. The most popular among them is Audacity, and its reputation is well deserved.

This editor offers all the capabilities of commercial audio editors:

- Simultaneous multitrack work, including monitoring

- Support for multiple file formats — import and export MP3, WAV, OGG, and more

- Noise reduction

- Time-stretching and pitch-shifting

- A wide range of effects, both built in and available as add-ons via plugins

Free assets!

You can find the art assets you need across the internet. On some sites, enthusiasts share their work for anyone to use. This helps artists, modelers, and musicians get their names out there and build a portfolio. If a game using their assets becomes popular, that’s a great point of pride — and something you can confidently mention in an interview. You can find such work, for example, on OpenGameArt.

Another source of art is the asset stores offered by engine vendors. Any engine with even a modest footprint has its own store. Unity has a massive Asset Store where you can buy just about anything a game developer could want: individual models, texture packs, animation sets, complete scenes, and even source code for finished projects packed with assets; storylines; tools to help game makers; services for building online and other types of games; extensions; and audio/visual effects. Many items are free. It’s a similar story with the Unreal Engine Marketplace. CryEngine has its own Marketplace offering a comparable range of items, though the selection is noticeably smaller.

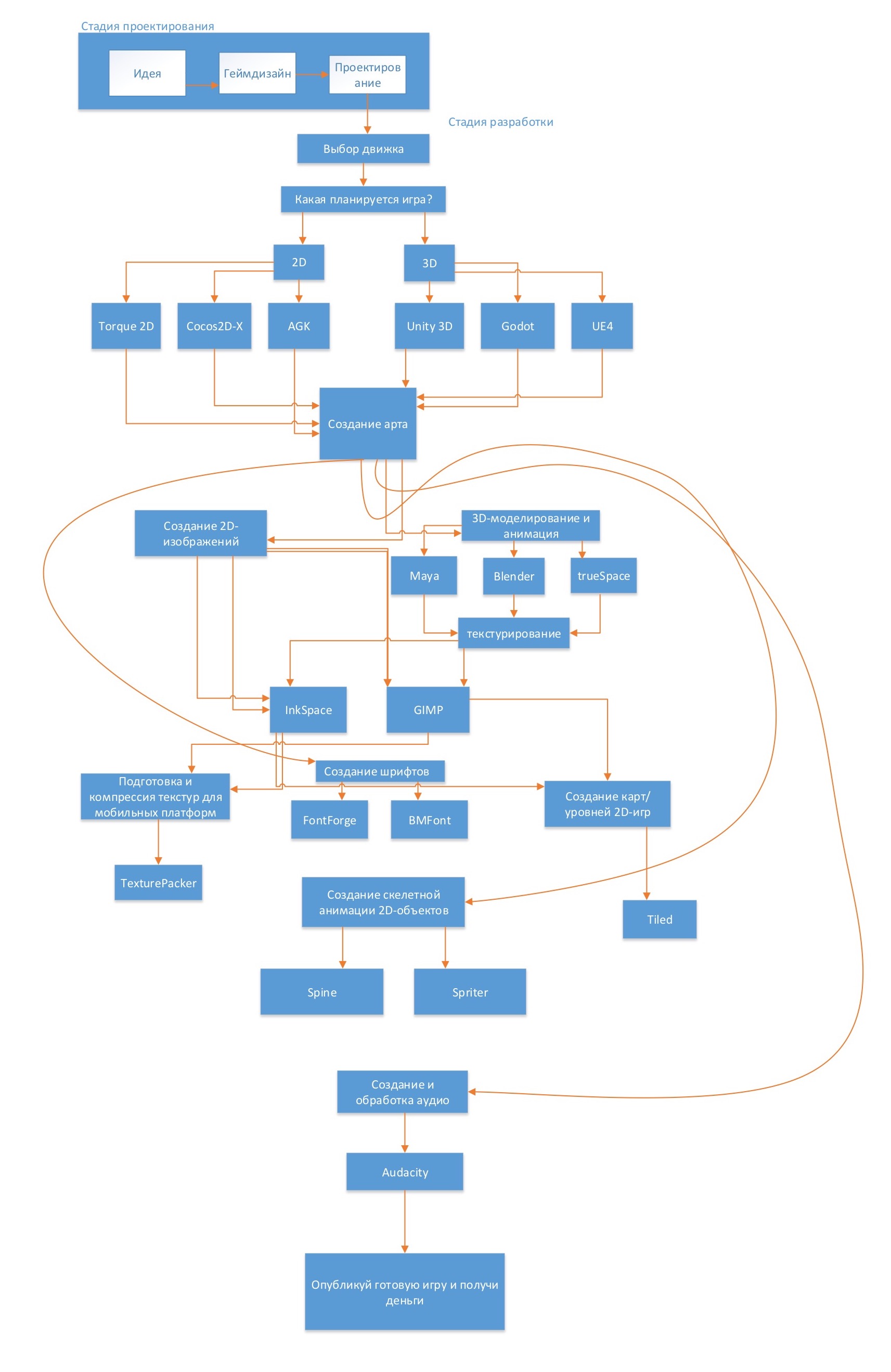

Summary diagram

Let’s summarize our findings in a single, comprehensive diagram.

Conclusion

I hope you found the article interesting and learned something new about game development tools. I didn’t try to cover every tool or single out any particular group. There are countless tools for making games. I simply focused on the set I use most often in my own projects.

When developing some games, it’s often easier to build a custom tool tailored to a single title. Later in development, this can save a lot of time when creating levels, minigames, or special mechanics.

If you’re into game dev too, don’t forget to share your favorite tools in the comments!