So, a data transfer protocol is an agreement between applications about the format of the data they exchange. For example, a server and client might use WebSocket together with JSON. Here’s how an Android app could request the weather from a server:

{ "request": "getWeather", "city": "cityname"}And the server could respond:

{ "success": true, "weatherHumanReadable": "Warm", "degrees": 18}Once it parses the response using a known schema, the app will present the information to the user. You can only parse such a packet if you know its structure. If you don’t, you’ll have to reverse-engineer the protocol.

Defining the Protocol’s Basic Structure

We’ll start with a minimal protocol for simplicity, but we’ll design it with an eye to expanding it and making it more sophisticated down the road.

The first thing to define is a custom header so applications can recognize packets of our protocol. We’ll use the byte sequence 0xAF, 0xAA, 0xAF. These bytes will appear at the beginning of every message.

info

Almost every binary protocol has a “magic number” (also called a “header” or “signature”)—a sequence of bytes at the start of a packet. It’s used to identify packets belonging to that protocol; all others are ignored.

Each packet will have a type and a subtype, each one byte long. That gives us 65,025 (255 × 255) distinct packet categories. A packet will contain fields, each identified by a unique one-byte ID, allowing up to 255 fields per packet. To ensure the application receives the packet in full—and to simplify parsing—we’ll add end-of-packet marker bytes.

Final packet structure:

XPROTOCOL PACKET STRUCTURE

(offset: 0) HEADER (3 bytes) [

(offset: 3) PACKET ID

(offset: 3) PACKET TYPE (1 byte)

(offset: 4) PACKET SUBTYPE (1 byte)

(offset: 5) FIELDS (FIELD[])

(offset: END) PACKET ENDING (2 bytes) [

FIELD STRUCTURE

(offset: 0) FIELD ID (1 byte)

(offset: 1) FIELD SIZE (1 byte)

(offset: 2) FIELD CONTENTS

Let’s call our protocol—as you’ve probably noticed—XProtocol. The packet type information starts at offset 3. The array of fields begins at offset 5. The packet is terminated by the bytes 0xFF and 0x00.

Implementing the Client and Server

To begin, specify the basic properties the package will have:

- packet type

- subtype

- set of fields

public class XPacket{ public byte PacketType { get; private set; } public byte PacketSubtype { get; private set; } public List<XPacketField> Fields { get; set; } = new List<XPacketField>();}Let’s add a class to represent a packet field that includes its data, ID, and length.

public class XPacketField{ public byte FieldID { get; set; } public byte FieldSize { get; set; } public byte[] Contents { get; set; }}Make the regular constructor private and add a static factory method to create a new instance.

private XPacket() {}public static XPacket Create(byte type, byte subtype){ return new XPacket { PacketType = type, PacketSubtype = subtype };}Now we can define the packet type and the fields it will contain. Let’s write a function for this. We’ll write to a MemoryStream. First, we’ll write the bytes of the header, the packet type, and the subtype, and then sort the fields by FieldID in ascending order.

public byte[] ToPacket(){ var packet = new MemoryStream(); packet.Write( new byte[] {0xAF, 0xAA, 0xAF, PacketType, PacketSubtype}, 0, 5); var fields = Fields.OrderBy(field => field.FieldID); foreach (var field in fields) { packet.Write(new[] {field.FieldID, field.FieldSize}, 0, 2); packet.Write(field.Contents, 0, field.Contents.Length); } packet.Write(new byte[] {0xFF, 0x00}, 0, 2); return packet.ToArray();}Now let’s write out all the fields. First come the field ID, its length, and the data. Only after that do we write the end-of-packet marker — 0xFF, 0x00.

Now it’s time to learn how to parse network packets.

info

The minimum packet size is 7 bytes: HEADER(3) + TYPE(1) + SUBTYPE(1) + PACKET (2)

We check the size of the incoming packet, its header, and the last two bytes. After validating the packet, we determine its type and subtype.

public static XPacket Parse(byte[] packet){ if (packet.Length < 7) { return null; } if (packet[0] != 0xAF || packet[1] != 0xAA || packet[2] != 0xAF) { return null; } var mIndex = packet.Length - 1; if (packet[mIndex - 1] != 0xFF || packet[mIndex] != 0x00) { return null; } var type = packet[3]; var subtype = packet[4]; var xpacket = Create(type, subtype); /* <---> */Time to move on to parsing the fields. Because the packet has a two-byte terminator, we can detect when the data to parse ends. Read the field ID and its SIZE, and add it to the list. If the packet is corrupted and you encounter a field with ID equal to zero and SIZE equal to zero, there’s no need to parse it.

/* <---> */ var fields = packet.Skip(5).ToArray(); while (true) { if (fields.Length == 2) { return xpacket; } var id = fields[0]; var size = fields[1]; var contents = size != 0 ? fields.Skip(2).Take(size).ToArray() : null; xpacket.Fields.Add(new XPacketField { FieldID = id, FieldSize = size, Contents = contents }); fields = fields.Skip(2 + size).ToArray(); }}The code above has an issue: if an attacker tampers with the size of one of the fields, parsing will either crash with an unhandled exception or parse the packet incorrectly. We need to make packet parsing safe. But we’ll get to that a bit later.

Reading and Writing Binary Data

Because of how the XPacket class is structured, fields have to store raw binary data. To assign a value to a field, we need to convert the value into a byte array. C# doesn’t offer an ideal built-in way to do this, so packets will only carry basic primitive types: int, double, float, and so on. Since these have a fixed size, we can read their bytes directly from memory.

To extract raw bytes of an object from memory, developers sometimes use unsafe code and pointers, but there are simpler options: the C# Marshal class lets you interact with unmanaged areas of your application. To convert any fixed-size object to bytes, we’ll use the following function:

public byte[] FixedObjectToByteArray(object value){ var rawsize = Marshal.SizeOf(value); var rawdata = new byte[rawsize]; var handle = GCHandle.Alloc(rawdata, GCHandleType.Pinned); Marshal.StructureToPtr(value, handle.AddrOfPinnedObject(), false); handle.Free(); return rawdata;}Here’s what we do:

- Get the size of our object.

- Create an array that will hold all the data.

- Obtain a handle to our array and write the object into it.

Now let’s do the same thing, but in reverse.

private T ByteArrayToFixedObject<T>(byte[] bytes) where T: struct{ T structure; var handle = GCHandle.Alloc(bytes, GCHandleType.Pinned); try { structure = (T) Marshal.PtrToStructure(handle.AddrOfPinnedObject(), typeof(T)); } finally { handle.Free(); } return structure;}You’ve just learned how to serialize objects to a byte array and deserialize them back. Now we can add functions to set and get field values. Let’s create a simple function to look up a field by its ID.

public XPacketField GetField(byte id){ foreach (var field in Fields) { if (field.FieldID == id) { return field; } } return null;}Let’s add a function to check if a field exists.

public bool HasField(byte id){ return GetField(id) != null;}Retrieve the value from the field.

public T GetValue<T>(byte id) where T : struct{ var field = GetField(id); if (field == null) { throw new Exception($"Field with ID {id} wasn't found."); } var neededSize = Marshal.SizeOf(typeof(T)); if (field.FieldSize != neededSize) { throw new Exception($"Can't convert field to type {typeof(T).FullName}.\n" + $"We have {field.FieldSize} bytes but we need exactly {neededSize}."); } return ByteArrayToFixedObject<T>(field.Contents);}By adding a few checks and using the function we’re already familiar with, we’ll convert the byte sequence from the field into the desired object of type T.

Setting a Value

We can only accept Value-Type objects. They have a fixed size, so we can write them.

public void SetValue(byte id, object structure){ if (!structure.GetType().IsValueType) { throw new Exception("Only value types are available."); } var field = GetField(id); if (field == null) { field = new XPacketField { FieldID = id }; Fields.Add(field); } var bytes = FixedObjectToByteArray(structure); if (bytes.Length > byte.MaxValue) { throw new Exception("Object is too big. Max length is 255 bytes."); } field.FieldSize = (byte) bytes.Length; field.Contents = bytes;}Sanity Check

We’ll test creating the packet, serializing it to binary, and parsing it back.

var packet = XPacket.Create(1, 0);packet.SetValue(0, 123);packet.SetValue(1, 123D);packet.SetValue(2, 123F);packet.SetValue(3, false);var packetBytes = packet.ToPacket();var parsedPacket = XPacket.Parse(packetBytes);Console.WriteLine($"int: {parsedPacket.GetValue<int>(0)}\n" + $"double: {parsedPacket.GetValue<double>(1)}\n" + $"float: {parsedPacket.GetValue<float>(2)}\n" + $"bool: {parsedPacket.GetValue<bool>(3)}");Looks like everything is working perfectly. You should see output in the console.

int: 123

double: 123

float: 123

bool: False

Defining packet types

Memorizing the IDs of all the packets you create is hard. Debugging a packet of type N with subtype Ns isn’t any easier if you’re trying to keep all the IDs in your head. In this section, we’ll give our packets human-readable names and map those names to their packet IDs. To start, we’ll create an enum that will hold the packet names.

public enum XPacketType{ Unknown, Handshake}Unknown will be used for an unknown type. Handshake is for the handshake packet.

Now that we know the packet types, it’s time to map them to IDs. We need to create a manager to handle this.

public static class XPacketTypeManager{ private static readonly Dictionary<XPacketType, Tuple<byte, byte>> TypeDictionary = new Dictionary<XPacketType, Tuple<byte, byte>>(); /* < ... > */}A static class is a good fit for this. Its constructor runs only once, which lets us register all known packet types. And because a static constructor can’t be called from the outside, we avoid re-registering those types.

Dictionary

public static void RegisterType(XPacketType type, byte btype, byte bsubtype){ if (TypeDictionary.ContainsKey(type)) { throw new Exception($"Packet type {type:G} is already registered."); } TypeDictionary.Add(type, Tuple.Create(btype, bsubtype));}Implement retrieving information by type:

public static Tuple<byte, byte> GetType(XPacketType type){ if (!TypeDictionary.ContainsKey(type)) { throw new Exception($"Packet type {type:G} is not registered."); } return TypeDictionary[type];}And, of course, extracting the packet type. The structure might look a bit messy, but it will work.

public static XPacketType GetTypeFromPacket(XPacket packet){ var type = packet.PacketType; var subtype = packet.PacketSubtype; foreach (var tuple in TypeDictionary) { var value = tuple.Value; if (value.Item1 == type && value.Item2 == subtype) { return tuple.Key; } } return XPacketType.Unknown;}Defining the Packet Format for Serialization and Deserialization

Instead of parsing everything by hand, let’s use class serialization and deserialization. To do this, create a class and add the appropriate attributes. The rest will be handled automatically by the code; you only need an attribute that specifies which field to read from and write to.

[AttributeUsage(AttributeTargets.Field)]public class XFieldAttribute : Attribute{ public byte FieldID { get; } public XFieldAttribute(byte fieldId) { FieldID = fieldId; }}Using AttributeUsage, we specified that our attribute can only be applied to class fields. FieldID will be used to store the field ID within the packet.

Building the serializer

In C#, you can use Reflection for serialization and deserialization. The reflection APIs let you discover the necessary metadata and set field values at runtime.

First, you need to collect information about the fields that will participate in the serialization process. You can do this with a simple LINQ expression.

private static List<Tuple<FieldInfo, byte>> GetFields(Type t){ return t.GetFields(BindingFlags.Instance | BindingFlags.NonPublic | BindingFlags.Public) .Where(field => field.GetCustomAttribute<XFieldAttribute>() != null) .Select(field => Tuple.Create(field, field.GetCustomAttribute<XFieldAttribute>().FieldID)) .ToList();}Since the required fields are marked with the XFieldAttribute, finding them inside the class is straightforward. First, retrieve all instance (non-static), private, and public fields using GetFields(). Filter down to the fields that have our attribute. Then build a new IEnumerable containing Tuple

info

Here we call GetCustomAttribute<>( twice. It’s not strictly necessary, but it makes the code look cleaner.

So now you can obtain all the FieldInfo for the type you’re going to serialize. It’s time to implement the serializer itself: it will support normal and strict modes. In normal mode, it will ignore cases where different fields reuse the same field ID within the packet.

public static XPacket Serialize(byte type, byte subtype, object obj, bool strict = false){ var fields = GetFields(obj.GetType()); if (strict) { var usedUp = new List<byte>(); foreach (var field in fields) { if (usedUp.Contains(field.Item2)) { throw new Exception("One field used two times."); } usedUp.Add(field.Item2); } } var packet = XPacket.Create(type, subtype); foreach (var field in fields) { packet.SetValue(field.Item2, field.Item1.GetValue(obj)); } return packet;}Inside the foreach loop is where the interesting part happens: fields contains all the required fields as Tuple

Implementing the Deserializer

Creating the deserializer is much simpler. We just need to use the GetFields( function we implemented in the previous section.

public static T Deserialize<T>(XPacket packet, bool strict = false){ var fields = GetFields(typeof(T)); var instance = Activator.CreateInstance<T>(); if (fields.Count == 0) { return instance; } /* <---> */Now that everything is set up for deserialization, we can proceed. Run the checks for strict mode, throwing an exception when necessary.

/* <---> */ foreach (var tuple in fields) { var field = tuple.Item1; var packetFieldId = tuple.Item2; if (!packet.HasField(packetFieldId)) { if (strict) { throw new Exception($"Couldn't get field[{packetFieldId}] for {field.Name}"); } continue; } /* A crucial workaround that simplifies things a lot * The GetValue<T>(byte) method takes the type as a type parameter * Our type is in field.FieldType * Using reflection, we invoke the method with the required type parameter */ var value = typeof(XPacket) .GetMethod("GetValue")? .MakeGenericMethod(field.FieldType) .Invoke(packet, new object[] {packetFieldId}); if (value == null) { if (strict) { throw new Exception($"Couldn't get value for field[{packetFieldId}] for {field.Name}"); } continue; } field.SetValue(instance, value); } return instance;}The deserializer is complete. Now we can verify that the code works. First, let’s create a simple class.

class TestPacket{ [XField(0)] public int TestNumber; [XField(1)] public double TestDouble; [XField(2)] public bool TestBoolean;}Let’s write a simple test.

var t = new TestPacket {TestNumber = 12345, TestDouble = 123.45D, TestBoolean = true};var packet = XPacketConverter.Serialize(0, 0, t);var tDes = XPacketConverter.Deserialize<TestPacket>(packet);if (tDes.TestBoolean){ Console.WriteLine($"Number = {tDes.TestNumber}\n" + $"Double = {tDes.TestDouble}");}After launching the program, two lines should appear:

Number = 12345

Double = 123,45

Now, let’s get to what all of this was built for.

Initial Handshake

A handshake is used in protocols to ensure the client and server agree on the same protocol and to validate the connection. In this case, the handshake will confirm whether the protocol is working.

www

You can find socket programming examples in the official documentation under Socket Code Examples.

We’ve built a simple library for handshake negotiation.

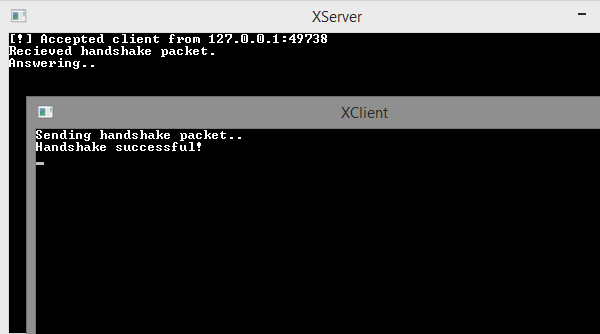

public class XPacketHandshake{ [XField(1)] public int MagicHandshakeNumber;}The client initiates the handshake. It sends a handshake packet containing a random number, and the server must reply with that number minus 15.

Send the packet to the server.

var rand = new Random();HandshakeMagic = rand.Next();client.QueuePacketSend( XPacketConverter.Serialize( XPacketType.Handshake, new XPacketHandshake { MagicHandshakeNumber = HandshakeMagic }).ToPacket());Upon receiving a packet from the server, we process the handshake in a dedicated function.

private static void ProcessIncomingPacket(XPacket packet){ var type = XPacketTypeManager.GetTypeFromPacket(packet); switch (type) { case XPacketType.Handshake: ProcessHandshake(packet); break; case XPacketType.Unknown: break; default: throw new ArgumentOutOfRangeException(); }}We deserialize it and validate the server’s response.

private static void ProcessHandshake(XPacket packet){ var handshake = XPacketConverter.Deserialize<XPacketHandshake>(packet); if (HandshakeMagic - handshake.MagicHandshakeNumber == 15) { Console.WriteLine("Handshake successful!"); }}On the server side, there’s an identical ProcessIncomingPacket. Let’s break down how the server processes a packet: we deserialize the client’s handshake packet, subtract fifteen, serialize it, and send it back.

private void ProcessHandshake(XPacket packet){ Console.WriteLine("Recieved handshake packet."); var handshake = XPacketConverter.Deserialize<XPacketHandshake>(packet); handshake.MagicHandshakeNumber -= 15; Console.WriteLine("Answering.."); QueuePacketSend( XPacketConverter.Serialize(XPacketType.Handshake, handshake) .ToPacket());}Build and test.

Everything works! 🙂

Implementing Basic Protocol Protection

Our protocol will have two packet types—regular and secure. The regular one uses our standard header, while the secure one uses this header: [.

To distinguish encrypted packets from regular ones, add a property to the XPacket class.

public bool Protected { get; set; }Next, we’ll update the XPacket.Parse(byte[]) function so it can accept and decrypt the new packets. We’ll start by modifying the header validation routine.

var encrypted = false;if (packet[0] != 0xAF || packet[1] != 0xAA || packet[2] != 0xAF){ if (packet[0] == 0x95 || packet[1] == 0xAA || packet[2] == 0xFF) { encrypted = true; } else { return null; }}What will our encrypted packet look like? Essentially, it’s a packet inside a packet—like that bag of bags you stash in the kitchen—only here the outer protected packet contains an encrypted normal packet.

Now we need to decrypt the encrypted packet and parse it. We also allow tagging a packet as the result of decrypting another packet.

public static XPacket Parse(byte[] packet, bool markAsEncrypted = false)Adding functionality to the field parsing loop.

if (fields.Length == 2){ return encrypted ? DecryptPacket(xpacket) : xpacket;}Since we only accept structs as data types, we can’t write a byte[] into a field. So we’ll tweak the code by adding a new function that takes a data array.

public void SetValueRaw(byte id, byte[] rawData){ var field = GetField(id); if (field == null) { field = new XPacketField { FieldID = id }; Fields.Add(field); } if (rawData.Length > byte.MaxValue) { throw new Exception("Object is too big. Max length is 255 bytes."); } field.FieldSize = (byte) rawData.Length; field.Contents = rawData;}Let’s make the same thing, but this time to read data from the field.

public byte[] GetValueRaw(byte id){ var field = GetField(id); if (field == null) { throw new Exception($"Field with ID {id} wasn't found."); } return field.Contents;}Everything is now ready to implement the packet decryption function. Encryption will use the RijndaelManaged class with a string as the encryption password. The password string will be constant. This encryption will help protect against MITM attacks.

Let’s create a class that will encrypt and decrypt data.

www

Since the encryption process is essentially the same, let’s take a ready-made solution from Stack Overflow for string encryption and adapt it to our needs.

Modify the methods so they accept and return byte arrays.

public static byte[] Encrypt(byte[] data, string passPhrase)public static byte[] Decrypt(byte[] data, string passPhrase)And a simple handler to store the secret key.

public class XProtocolEncryptor{ private static string Key { get; } = "2e985f930853919313c96d001cb5701f"; public static byte[] Encrypt(byte[] data) { return RijndaelHandler.Encrypt(data, Key); } public static byte[] Decrypt(byte[] data) { return RijndaelHandler.Decrypt(data, Key); }}Next, we create a decryption function. The data must be in the field with ID 0—how else are we supposed to find it?

private static XPacket DecryptPacket(XPacket packet){ if (!packet.HasField(0)) { return null; } var rawData = packet.GetValueRaw(0); var decrypted = XProtocolEncryptor.Decrypt(rawData); return Parse(decrypted, true);}Retrieve the data, decrypt it, and parse it again. Repeat the same for the reverse process.

Add a property that flags whether the encrypted packet header is required.

private bool ChangeHeaders { get; set; }We create a simple packet and flag it as carrying encrypted data.

public static XPacket EncryptPacket(XPacket packet){ if (packet == null) { return null; } var rawBytes = packet.ToPacket(); var encrypted = XProtocolEncryptor.Encrypt(rawBytes); var p = Create(0, 0); p.SetValueRaw(0, encrypted); p.ChangeHeaders = true; return p;}And we’ll add two helper functions to make it easier to use.

public XPacket Encrypt(){ return EncryptPacket(this);}public XPacket Decrypt() { return DecryptPacket(this);}Modify ToPacket( so it honors the ChangeHeaders value.

packet.Write(ChangeHeaders ? new byte[] {0x95, 0xAA, 0xFF, PacketType, PacketSubtype} : new byte[] {0xAF, 0xAA, 0xAF, PacketType, PacketSubtype}, 0, 5);Let’s check:

var packet = XPacket.Create(0, 0);packet.SetValue(0, 12345);var encr = packet.Encrypt().ToPacket();var decr = XPacket.Parse(encr);Console.WriteLine(decr.GetValue<int>(0));In the console, we get the number 12345.

Conclusion

We’ve just created our own protocol. It’s been a long road from a basic design on paper to a complete implementation in code. I hope you found it interesting!

The project’s source code is available on my GitHub.