info

This article was written by the HackMag Editorial Board based on the Fuzzing the Linux kernel talk by Andrey Konovalov. The article was reviewed by the speaker, and the information is presented in the first person with his permission.

When I mention attacking USB, people usually think about Evil HID – a BadUSB-like attack. It involves a USB device that looks harmless, like an ordinary flash drive, but, once connected, acts as a keyboard that automatically opens the console and starts typing malicious commands.

In the course of my fuzzing-related work, such attacks were of no interest to me. Instead, I was looking for kernel memory corruptions. The attack scenario is similar to BadUSB: you plug in a specially crafted USB device, and it starts its malicious activity. The difference is that this device doesn’t type commands pretending to be a keyboard, but exploits a vulnerability in a USB driver and executes arbitrary code in the kernel.

Over the years I worked on kernel fuzzing, I’ve been reading and collecting fuzzing-related publications. So, I organized them and turned into a talk. Today, I will describe several kernel fuzzing approaches and give some advice to novice researchers interested in this topic.

What is fuzzing

Fuzzing is a way to find bugs in programs.

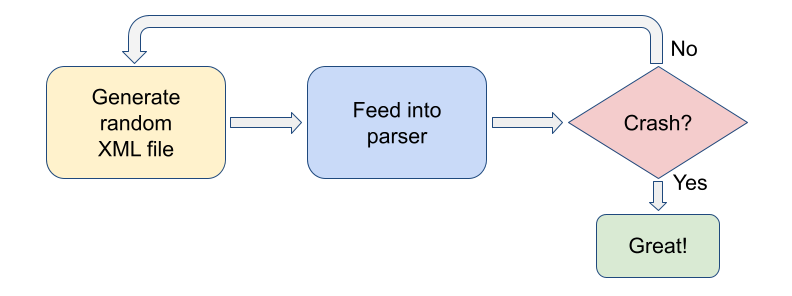

How does it work? You generate random data, pass it into a program as input, and check whether the program crashed. If it didn’t crash, you generate more random data. If it did – perfect, you have found a bug. It’s assumed that the program shouldn’t crash from unexpected data; it should successfully process it instead.

Here’s an example: you take an XML parser and start feeding randomly generated XML files to it. Once the parser crashes – you have found a bug in it.

Fuzzing can be used to test anything that processes data. This includes apps and libraries in the userspace, the kernel, firmware, or even hardware.

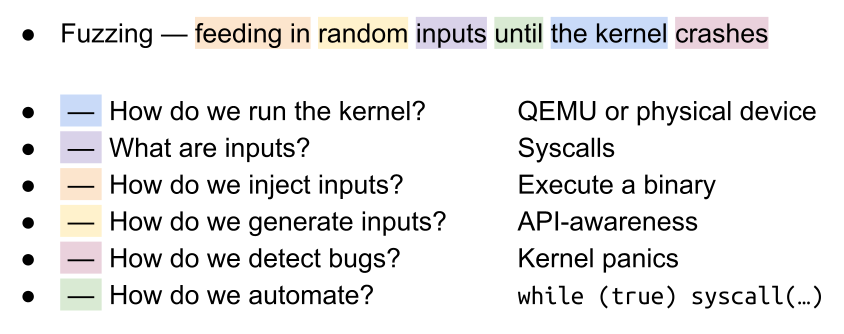

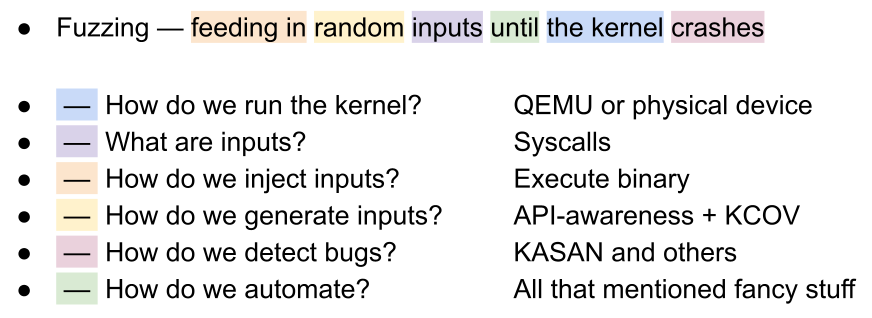

When you start working on a fuzzer for a specific program, you need to answer the following questions:

- How to run this program? In the case of a userspace app, you just execute the binary. But running the kernel or firmware components isn’t that easy.

- What are inputs? An “input” is the data passed to the program for processing. For an XML parser, it’s XML files, while browsers process HTML and execute JavaScript.

- How to inject inputs? In the simplest case, the data is passed through the standard input or as a file. But programs can receive data via other channels. For instance, firmware can get it from physical devices.

- How to generate inputs? You can use arrays of random bytes as inputs, or you can do something more sophisticated.

- How to detect bugs? When the program crashes, it’s a bug. But some bugs don’t result in crashes (for instance, information leaks). However, it’s preferable to detect these kinds of bugs as well.

- How to automate the process? You can keep manually launching the program, feeding new data to it, and checking if it crashed. Or you could write a script that does this automatically.

This article is focused on the Linux kernel, so you can replace the word “program” with “Linux kernel” in each of these questions. Now, let’s try to figure out the answers.

Legacy approach

Let’s figure out a few simple answers to these questions and thus come up with a basic fuzzing approach.

Running the kernel

First, you need to somehow run the kernel. There are two main ways to do this: use physical devices (PCs, phones, or single-board computers) or use virtual machines – VMs (e.g. QEMU). Each way has its own pros and cons.

If you use hardware, the kernel is running as it runs in real-world scenarios. For instance, native device drivers are available (unlike a VM, where you only have access to the features it supports).

On the other hand, hardware is less handy than VMs: it’s harder to update the kernel, reboot the crashed system, and collect logs. Virtual machines are way better from this point of view.

Another advantage of virtual machines is their scalability. To run your fuzzer on a large number of physical devices, you have to buy them, which can be expensive or complicated logistically. To scale up fuzzing in virtual machines, you can take a powerful PC and run as many VM instances as you want.

Considering pros and cons of each method, the use of VMs seems to be preferable. But first, let’s figure out the answers to the rest of the questions. Perhaps, there’s a fuzzing approach that works well regardless of the way the kernel is run.

Generating inputs

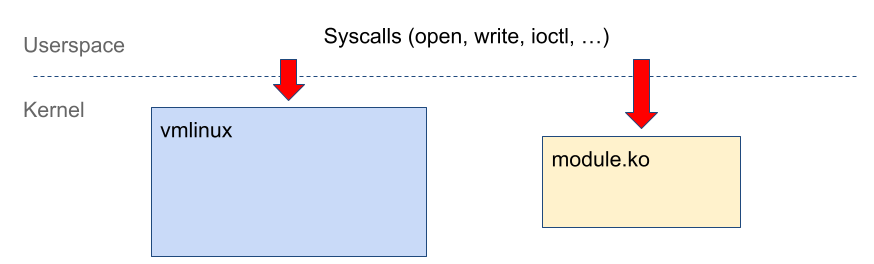

What are kernel inputs? The kernel handles system calls (syscalls). How to pass an input to the kernel? Write a program that makes a sequence of syscalls, compile it into a binary, and run it. That’s it: the kernel will now be interpreting your input.

Now, let’s figure out what data to pass to syscalls as arguments and in what order to call them.

The simplest way to generate data is to take random bytes. But this method does not work well: programs, including the kernel, usually expect to receive data in a predefined form. If you pass garbage to them, even the basic correctness checks will fail, and the program will refuse to process the input further.

A better way is to generate data based on a grammar. For instance, for an XML parser, you can use a grammar that describes an XML file as a sequence of XML tags. This allows to pass basic sanity checks and penetrate deeper into the parser’s code.

However, this approach needs to be adapted prior to being applied to the kernel. A kernel input is a sequence of syscalls with arguments, not just an array of bytes (even if it’s generated according to a grammar).

Consider a program consisting of three syscalls: open, which opens a file; ioctl, which performs an operation with that file; and close, which closes the file.

int fd = open("/dev/something", …);ioctl(fd, SOME_IOCTL, &{0x10, ...});close(fd);For open, the first argument is a string, which can be considered a simple structure with a single fixed field. For ioctl, the first argument is the value returned by open, and the third one is a complex structure with several fields. Finally, the result returned by open is also passed to close.

This program is a typical input the kernel processes. In other words, kernel inputs are sequences of syscalls whose arguments are structured and whose results can be passed from one syscall to another.

Overall, this resembles a library API: its calls take structured arguments and return results that can be passed to subsequent calls. Therefore, when you fuzz the kernel using syscalls, you essentially fuzz the API provided by the kernel. I call this approach “API-aware fuzzing”.

Unfortunately, in the case of the Linux kernel, there is no exact documentation of all possible syscalls and their arguments. There were several attempts to generate this information automatically, but none of them produced comprehensive results. Therefore, the only way to know what syscalls are there and what arguments do they expect is to figure it out by hand.

So, let’s select several syscalls and develop an algorithm to generate their sequences. For instance, let’s make this algorithm use the result of open and structures of proper types with random fields as ioctl arguments.

[Not] automating

Let’s not bother with automation just yet: the fuzzer will generate inputs in a loop and pass them to the kernel. And you will manually monitor the kernel log for errors (e.g. kernel panics).

Done

Perfect! The provided answers define a simple approach to kernel fuzzing.

The fuzzer represents a single binary that randomly invokes certain syscalls with more or less correct arguments. Since a binary can be run both on virtual machines and physical devices, the fuzzer is universal in this sense.

Although the answers were pretty straightforward, this approach works great. If you ask a Linux kernel security expert: “Which fuzzer works this way?”, the answer will be: “Trinity”! Yes, this kind of fuzzer already exists. One of its advantages is portability. You just drop the binary into any system, run it, and start hunting for kernel bugs.

Foundational approach

Trinity was created a long time ago, and scientific thought in the field of fuzzing has made notable progress since then. Let’s try to enhance Trinity’s approach by using modern ideas.

Collecting coverage

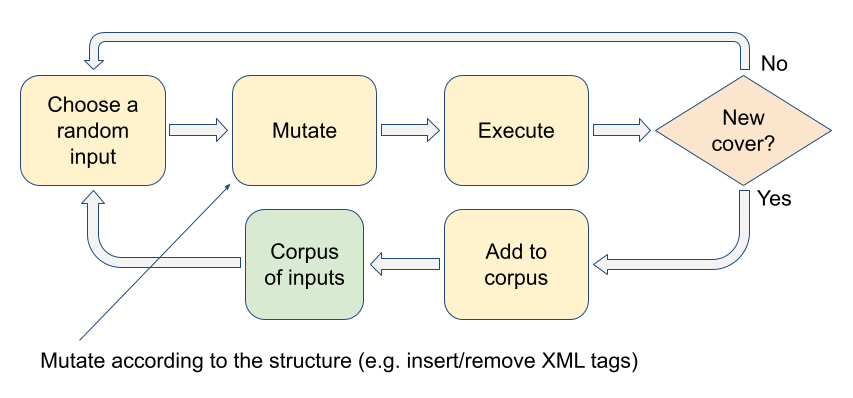

The first idea is to apply the coverage-guided approach to input generation.

How does it work? In addition to generating random inputs from scratch, you have a set of previously generated ‘interesting’ inputs called corpus. Sometimes, instead of a random input, you take an input from the corpus and slightly modify it. Then you execute the program with the mutated input and check whether it’s ‘interesting’. An input is ‘interesting’ if during its execution the program covers code that wasn’t covered by previously executed inputs. Basically, if the new input allows you to penetrate deeper into the program, you add it to the corpus. This way, you gradually get further and further as more and more interesting programs are being added to the corpus.

This approach is used by the two main userspace fuzzing tools: AFL and libFuzzer.

Coverage-guided approach can be combined with the use of grammar. When you mutate a structure, you can do it according to its grammar instead of just flipping bytes randomly. If the input is a sequence of syscalls, then you can mutate it by adding or removing calls, rearranging them, or changing their arguments.

For coverage-guided Linux kernel fuzzing, you need a tool that collects code coverage from the kernel. KCOV was developed for this purpose. It requires access to the kernel source code, which is usually available. To use KCOV, you have to rebuild the kernel with the CONFIG_KCOV option enabled. After that, you can collect code coverage via /.

info

KCOV allows to collect kernel code coverage from the current thread ignoring background processes. This way, the fuzzer only collects relevant coverage that corresponds to the syscalls it executes.

Detecting bugs

Now, let’s figure out a better way to detect kernel bugs than waiting for a kernel panic.

A panic works poorly as a bug indicator. First, some bugs don’t cause it (e.g. the above-mentioned info-leaks). Second, in case of a memory corruption, kernel panic might occur much later than the corruption itself. In this case, it’s hard to localize the bug: it’s unclear which of the recent fuzzer actions has caused it.

To solve these problems, dynamic bug detectors have been invented. The word “dynamic” means that these detectors work while the program is running. They analyze its actions based on their algorithm and report an abnormal situation when it’s detected.

There are a few dynamic bug detectors for the Linux kernel. The most notable one is KASAN. It’s notable not because I worked on it, but because it detects the main types of memory corruptions: out-of-bounds and use-after-free accesses. To use KASAN, enable the CONFIG_KASAN option and rebuild the kernel. KASAN will be running in the background and report identified bugs to the kernel log.

info

Learn more about dynamic bug detectors for the Linux kernel from the Mentorship Session: Dynamic Program Analysis for Fun and Profit talk by Dmitry Vyukov (slides).

Automating

There are plenty of things that can be automated when it comes to fuzzing, including:

- monitoring kernel logs for crashes and reports of dynamic detectors;

- restarting virtual machines with crashed kernels;

- trying to reproduce crashes by rerunning the last few inputs that were executed right before the crash; and

- reporting found bugs to kernel developers.

How to implement all these functions? Write the code and add it to your fuzzer. A purely engineering task.

All together

Let’s put together the three ideas discussed above – coverage-guided fuzzing, dynamic detectors, and automation – and incorporate them into the fuzzer. The overall picture becomes as follows.

Now, if you ask an expert what kernel fuzzer uses these approaches, the answer will be: “syzkaller”. Currently, syzkaller is the most advanced public Linux kernel fuzzer. It has found thousands of bugs, including multiple exploitable vulnerabilities. Many people involved with Linux kernel fuzzing use this tool.

info

Some people believe that KASAN is an integral part of syzkaller. This is not true: KASAN can be used with Trinity, as well as syzkaller can be used without KASAN.

Charged ideas

The application of syzkaller’s ideas is a solid approach to kernel fuzzing. But let’s go further and explore other notable methods.

Running kernel code in userspace

So far, I mentioned two ways to run the kernel for fuzzing purposes: using virtual machines and using physical devices. But there is a third way: you can pull the kernel code into userspace. To do this, you have to take some isolated subsystem and compile it as a library. Then you can fuzz it with userspace fuzzing tools.

For some subsystems, pulling the code to userspace isn’t difficult. If a subsystem allocates memory with kmalloc, frees it with kfree, and these are the only kernel functions it uses, then you can replace kmalloc with malloc and kfree with free. After that, you can compile the code as a library and fuzz it using the above-mentioned libFuzzer.

However, for most subsystems, this approach would cause problems. The required subsystem may use an API that is not available in userspace (e.g. RCU).

info

RCU (Read-Copy-Update) is a synchronization mechanism used in the Linux kernel.

Another disadvantage of this approach is that the kernel code you have pulled into userspace might be updated, and then you’ll have to pull it out again. Of course, you can try to automate this process, but this might not be easy to implement.

Still, this approach was used to fuzz eBPF, ASN.1 parsers, and the networking subsystem of the XNU kernel.

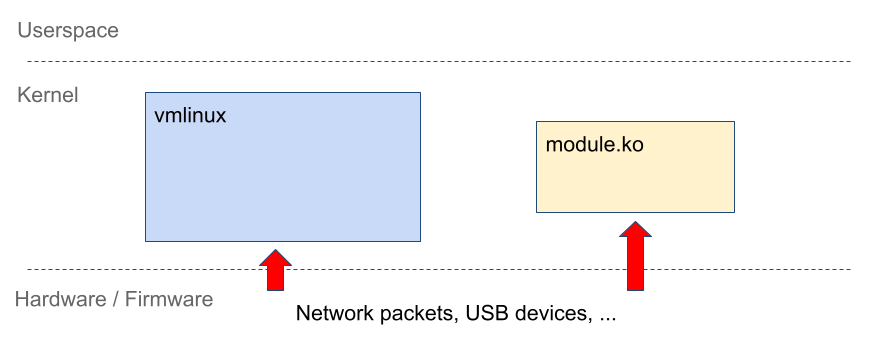

Fuzzing external interfaces

Syscalls are used to pass data from userspace to the kernel. But since the kernel is a layer between user programs and the hardware, it also receives inputs from the device side.

In other words, the kernel processes data received over Ethernet, USB, Bluetooth, NFC, mobile networks, and other hardware protocols.

For instance, you send a TCP packet to the system. The kernel must parse it in order to understand which port the packet was sent to and what app it should be delivered to. By sending randomly generated TCP packets, you can fuzz the kernel network subsystem from the external side.

But how to pass data into the kernel over external interfaces? Syscalls can be injected by executing a binary, but this approach won’t work if you want to communicate with the kernel via USB.

You can transmit data using hardware: for instance, send network packets over a network cable or use Facedancer for USB. Unfortunately, this approach doesn’t scale. Instead, it would be great to use virtual machines.

There are two solutions.

The first one is to write your own driver, and plug it into the proper place in the kernel to simulate the delivery of data over a hardware protocol (you will use syscalls to pass data to the driver). For certain interfaces, such drivers are already present in the kernel.

For instance, I fuzzed the network subsystem via TUN/TAP. This interface allows injecting network packets into the kernel, and these packets go through the same parsing paths as if they were received from an external sender. For USB fuzzing, I had to write my own driver.

The second solution is to pass the input to the VM’s kernel from the host. If the virtual machine emulates a network card, it can also emulate a packet going through this network card.

This approach is utilized in the vUSBf fuzzer. It uses QEMU and the usbredir protocol making it possible to connect USB devices to the virtual machine’s kernel from the host side.

Beyond the scope of API-aware fuzzing

What is a syscall? On the one hand, it’s a sequence of calls with structured arguments where result of one syscall can be used in another one. However, not all syscalls work in this simple way.

Take, for instance, clone and sigaction. Yes, they also accept arguments and can return a result. However, they spawn another execution thread. Clone creates a new process, while sigaction allows you to set up a signal handler to pass the control to when a signal comes.

A fuzzer that targets these syscalls must take such features into account (e.g. fuzz from each spawned execution thread).

Complex subsystems

Instead of taking simple structures as inputs, some subsystems (e.g. eBPF and KVM) accept sequences of executable instructions. Generating a correct chain of instructions is a much more difficult task than generating a correct structure. Specialized fuzzers are required for these subsystems. Something like fuzzilli, a fuzzer for JavaScript interpreters.

Structuring external inputs

Imagine you fuzz the network subsystem externally. It might seem that fuzzing via network packets is limited to generating and sending regular structures. But in fact, the network operates as an API from the external point of view.

Consider fuzzing TCP. Let’s say there is a socket on the host, and you want to connect to it over the network. It seems simple: you send a SYN, the host responds with a SYN/ACK, you send an ACK – and that’s it, the connection is established. But the received SYN/ACK packet contains the acknowledgment number that you must insert into your ACK packet. Essentially, this number is a return value sent by the kernel to the external actor.

In other words, the external interaction with a TCP socket over the network involves a sequence of calls (sending packets) whose return values (acknowledgment numbers) are used in subsequent calls. Therefore, the network operates as an API, and the API-aware fuzzing ideas are applicable here.

USB

USB is an unusual protocol: all communication is initiated by the host. Therefore, even if you find a way to connect USB devices for fuzzing purposes, you can’t simply send data to the host. Instead, you have to wait for a request from the host and respond to this request. Unfortunately, you don’t always know what request is going to come next. A suitable fuzzer for the USB protocol must take this feature into account.

Alternatives to KCOV

How else can you collect kernel code coverage (aside from using KCOV)?

First, you can use emulators. Imagine a virtual machine emulating the kernel instruction by instruction. You can hack into the emulation loop and collect instruction addresses from there. An advantage of this approach is that, unlike KCOV, you don’t need the kernel source code. As a result, this method can be applied to proprietary kernel modules that are only available as binaries. This is how the TriforceAFL and UnicoreFuzz fuzzers work.

Another way is to collect coverage using hardware features of the CPU. For instance, kAFL uses Intel PT.

Note, that the above-mentioned implementations of these approaches are experimental and need refinement for practical usage.

Collecting relevant coverage

For coverage-guided fuzzing, you need to collect code coverage relevant to the subsystem you are fuzzing.

Collecting coverage from the current thread doesn’t always work: the subsystem may handle inputs in other contexts. A syscall might create a new kernel thread and process the input there. For instance, USB packets are processed in global threads that are launched during the kernel boot and aren’t bound to any userspace context.

To solve this issue during my fuzzing endeavors, I implemented in KCOV the possibility to collect coverage from background threads and softirqs. This feature requires adding annotations to the code sections you want to collect coverage from.

Beyond the scope of code coverage

Relying on code coverage isn’t the only way to guide the fuzzing process.

For instance, by tracking the state of kernel memory areas or its internal objects, you can see what inputs change this state and add them to the corpus.

The more complex kernel state is achieved during fuzzing, the greater is the chance that you encounter a situation the kernel doesn’t handle correctly.

Collecting a seed corpus

Another way to generate inputs is to do it based on actions of existing programs. They might interact with the kernel in nontrivial ways and penetrate deep into the kernel code. Even a very smart fuzzer might not be able to generate sequences of syscalls that lead to such interactions from scratch.

This approach is utilized in the Moonshine project: its authors ran some system tools under strace, collected a log from them, and used the resulting sequences of syscalls as seed corpus for fuzzing with syzkaller.

Detecting more bugs

The existing dynamic detectors aren’t perfect and can’t detect certain types of bugs. How to find such bugs? Enhance the detectors!

You can, for instance, take KASAN (to remind: it finds memory corruptions) and add annotations for some new allocator. By default, KASAN supports the standard kernel allocators such as slab and page_alloc. But there are drivers that allocate a large memory chunk of memory and then break it into smaller blocks, essentially implementing a custom allocator (hello Android!). In this case, KASAN won’t be able to find an overflow from one block to another. This requires to manually add annotations for this allocator.

There is also another tool called KMSAN that can detect information leaks. By default, it searches for leaks of kernel data to userspace. But data can also leak through external interfaces: over the network or USB. KMSAN can be specially modified to detect such leaks too.

You can also create your own bug detectors from scratch. The easiest way is to add asserts to the kernel code. If you know that a certain condition must always be met in a certain place, just add BUG_ON and start fuzzing. If BUG_ON gets triggered, then you have found a bug (and also created a basic logical error detector). Such detectors are of special interest when fuzzing eBPF, because eBPF errors usually don’t result in memory corruption and go unnoticed.

Summary and tips

Overall, there are three approaches to Linux kernel fuzzing:

- Using a userspace fuzzer. You either take a fuzzer like AFL or libFuzzer and make it call syscalls instead of functions of a userspace program. Or you pull the kernel code into userspace and fuzz it there. These methods work fine for subsystems that process structures because userspace fuzzers are primarily focused on byte array mutations. Examples: fuzzing file systems and Netlink. For coverage-guided fuzzing, you have to integrate coverage collection from the kernel into the fuzzing algorithm.

- Using syzkaller. It’s perfect for API-aware fuzzing. The fuzzer uses a special language, syzlang, to describe syscalls and their return values and arguments.

- Writing your fuzzer from scratch. This is a great way to learn how fuzzing works from the ground up. In addition, this approach enables you to fuzz subsystems with unusual interfaces.

Syzkaller tips

- Don’t just use syzkaller on a standard kernel with a standard config – you won’t find anything. Many researchers fuzz the kernel, both manually and with syzkaller. In addition, there is syzbot, which has been fuzzing many standard kernel flavors in the cloud for years. Do something new instead: write new syscall descriptions or use a nonstandard kernel config.

- Syzkaller can be improved and extended. When I was fuzzing USB, I implemented an additional USB-specific module on top of syzkaller.

- Syzkaller can be used as a framework. For instance, you can only use the code that parses the kernel log. Syzkaller recognizes hundreds of different error report types, and you may use this component in your fuzzer. Or you can use the virtual machine management code instead of writing it yourself.

How do you know whether your fuzzer is working well? Of course, if it finds new bugs, everything is fine. But what if it doesn’t?

- Check code coverage. If you are fuzzing a specific subsystem, make sure that your fuzzer covers all of its interesting parts.

- Add artificial bugs to the subsystem you fuzz. For instance, add asserts and check whether the fuzzer can reach them. This recommendation is similar to the previous one, but it works even if your fuzzer doesn’t collect code coverage.

- Revert patches for fixed bugs and make sure your fuzzer finds them.

If your fuzzer covers all of the code you are interested in and finds previously fixed bugs, most likely it’s working as intended. If it doesn’t find new bugs, then either the code is indeed bug-free, or the fuzzer doesn’t put the kernel in a sufficiently complex state.

Two final tips:

Write the fuzzer based on the code, not documentation. Documentation may be inaccurate. The source of truth is always the code. For instance, while working on my USB fuzzer, I noticed that the subset of protocols actually supported by the kernel is different from the one described in the documentation. Relying on documentation only would make me miss a part of functionality that could be fuzzed.

Focus on making the fuzzer smart before making it fast. “Smart” means generating accurate inputs, collecting relevant coverage, etc. “Fast” means processing more inputs per second. For more information on the “smart vs. fast” issue, see this article and this discussion.

Conclusions

Developing fuzzers is engineering work that requires engineering skills: systems design, programming, testing, debugging, and benchmarking.

This leads to two conclusions. First, to implement a simple fuzzer you only need basic programming skills. Second, to write an outstanding fuzzer, you need excellent engineering skills. The main reason why syzkaller is so successful is the huge amount of engineering experience and time invested into it.

That’s it! I am looking forward to seeing a new original fuzzer written by you!

www

See more materials about Linux kernel fuzzing and exploitation in my GitHub collection and on the LinKerSec Telegram channel.