DNS: the Internet’s shaky glue

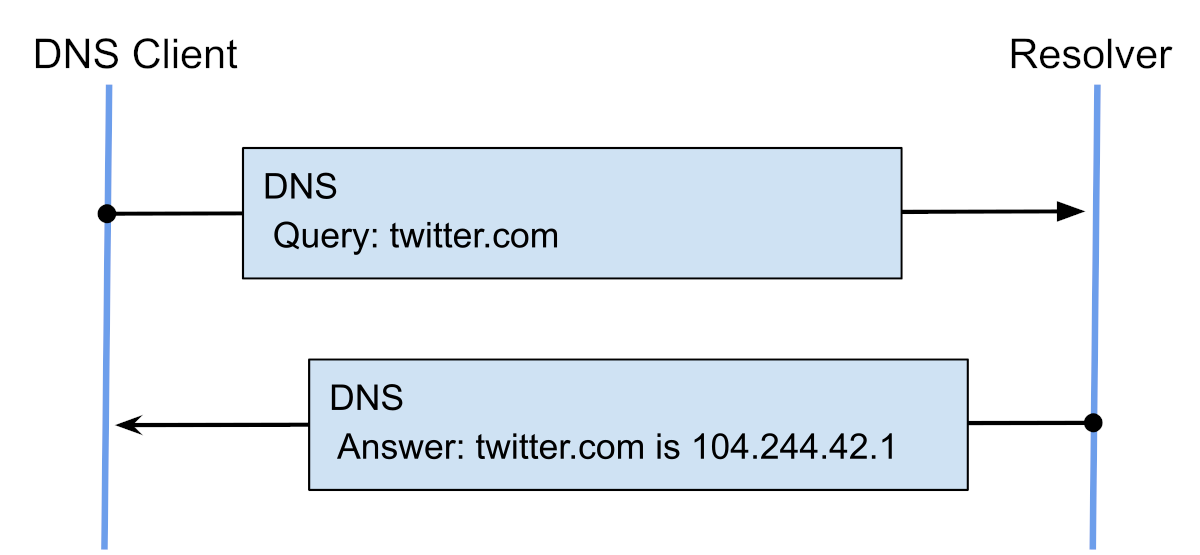

For the sake of structure and continuity, let’s briefly revisit the key concepts. The Domain Name System DNS is one of the core technologies underpinning the modern Internet. It maps numeric IP addresses to human-friendly domain names and is organized as a hierarchical system of interacting DNS servers.

One key point: this system was designed back in 1983, so it has some inherent security shortcomings. At the time, the internet was a network linking U.S. research and military institutions, and opening it up to the general public wasn’t part of the plan.

In short, the root of the problem is that the basic DNS system accepts and forwards any queries it receives. As with many other designs from the early days of the internet, there’s no built-in protection against malicious use. At the time, simplicity and scalability were the primary goals.

As a result, various methods of attacking DNS servers emerged (for example, DNS cache poisoning and DNS hijacking). The outcome of such attacks is that users’ browsers are redirected to places they never intended to visit.

To address these issues, the Internet Engineering Task Force developed the DNSSEC extensions, adding public‑key digital signatures to DNS. But the work took a long time. The problem had become apparent in the early 1990s; by 1993 the direction was set, the first version of DNSSEC was ready by 1997, there were attempts to deploy it—and then the revisions started…

By 2005, a version suitable for large-scale deployment had been created, and rollout began by propagating the chain of trust across Internet zones and DNS servers. The deployment took a long time too—for example, the .com zone wasn’t signed until March 2011.

info

If you want to dig deeper into the threats DNSSEC was meant to protect DNS against, take a look at this report, a 2004 threat analysis from the Internet Engineering Task Force. As the authors note, a decade after the work began it was time to take stock of which problems they intended to tackle and how.

But DNSSEC only addresses part of the problem—it guarantees authenticity and integrity of the data, but not privacy. Encryption is the natural way to achieve that. The question is how exactly to implement it.

Encryption methods

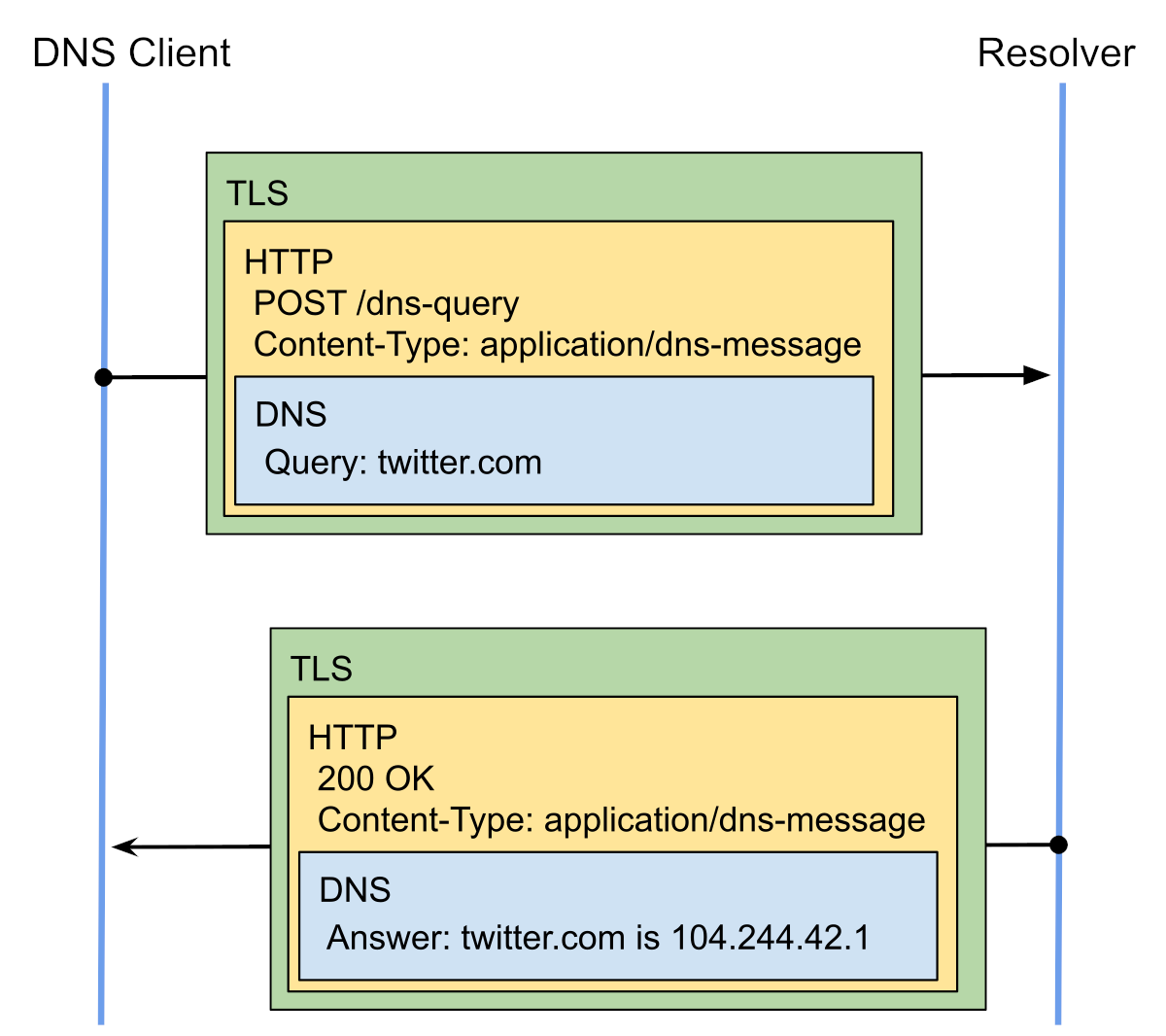

Several developer groups have proposed different technical approaches. Some of them use novel encryption schemes, such as DNSCrypt or DNSCurve, which relies on elliptic-curve cryptography. However, the solutions that have seen broader adoption build on the widely used TLS security protocol. These include DoT (DNS over TLS) and DoH, the main focus of this article.

As the name implies, DoT uses TLS itself to encrypt DNS queries. This changes the default transport and port: instead of UDP/53, it uses TCP/853.

DoH is built differently and uses TLS in a different way. With DoH, TLS operates at the HTTPS layer: DNS queries are sent as HTTPS requests to the DNS server over its standard web ports.

Sounds complicated? Jan Schaumann explains it clearly and to the point:

Since HTTPS uses TLS, you could be pedantic and claim that technically DoH is just DNS over TLS. But that would be wrong. DoT sends native DNS protocol messages over a TLS connection on a dedicated port. DoH, by contrast, uses the HTTP application-layer protocol to send DNS queries to a server’s HTTPS port, leveraging—and including—all the usual elements of HTTP messages.

DoH: Let’s get to the point

At this point, it’s reasonable to ask: what could possibly be the problem here? The more security, the better—right?

The answer lies in the nuances of the chosen solution—its strengths and weaknesses. Specifically, it’s about how the new technology interacts with the various players in the DNS ecosystem: which ones its designers implicitly trust, and which they treat as sources of risk. And we’re not even talking about malicious hackers with overtly criminal intent.

The point is that there are intermediaries between a user’s device and the destination website. Network administrators, firewalls, and ISPs can interact with the DNS system by configuring their DNS resolvers to decide which queries to monitor, block, or modify. This can be used to inject ads, filter out malicious content, or block access to certain resources.

DoT, despite running over TLS with its certificate-based trust model, still needs a DNS resolver it can trust. There’s flexible configuration to define a list of trusted resolvers, support for centrally managing settings in a pre-trusted environment (e.g., a corporate network), and the ability to fall back to plain DNS if the new version causes problems.

Because DoT uses a dedicated port, the traffic is easy to spot and its volume can be monitored—encryption doesn’t prevent that. If desired, you can even block it outright.

In short, DoT needs careful configuration, but it offers features that are extremely useful for system administrators and network engineers. That’s why many professionals praise it.

DoH is a different story. It was designed with end-user applications in mind—specifically, browsers. That’s the crucial detail here. Here’s what it means: when DoH is enabled, all non-browser traffic still uses the system’s regular DNS, but browser traffic ignores DNS settings at the OS, local network, and ISP levels and, bypassing those intermediaries, goes over HTTPS directly to a DoH-enabled DNS resolver.

And this scheme raises a number of serious questions.

Sinister Villains and Conspiracy Theories

Now we’ve reached the part about who nominated Mozilla for “Internet Villain of the Year.” It was the UK’s Internet Service Providers’ Association and the British Internet Watch Foundation. These organizations are involved in blocking unwanted content for UK internet users. Their main focus is combating child sexual abuse material, but they’re also concerned with piracy, extremism, and other criminal activity. At one point they even tried to ban BDSM pornography for UK internet users, but failed.

These organizations believe that rolling out DoH will significantly limit their ability to control access to content. Their concerns are shared not only by ISPs in other countries, but also by cybersecurity professionals, who note that firewall and DNS monitoring system developers will face the same challenges. As a result, corporate network defenses could be weakened, and employees could gain new avenues to download malware via phishing links. Moreover, there are already examples of attackers abusing DoH.

In the United States, Google and Mozilla entered a legal battle with ISPs over DoH. First, the ISPs submitted a written request to the U.S. Congress to examine the potential consequences of deploying DoH. Google managers promptly assured everyone that the risks were overstated. Mozilla, meanwhile, asked Congress to scrutinize ISPs’ user data collection practices, openly suggesting that providers were defending their own vested interests.

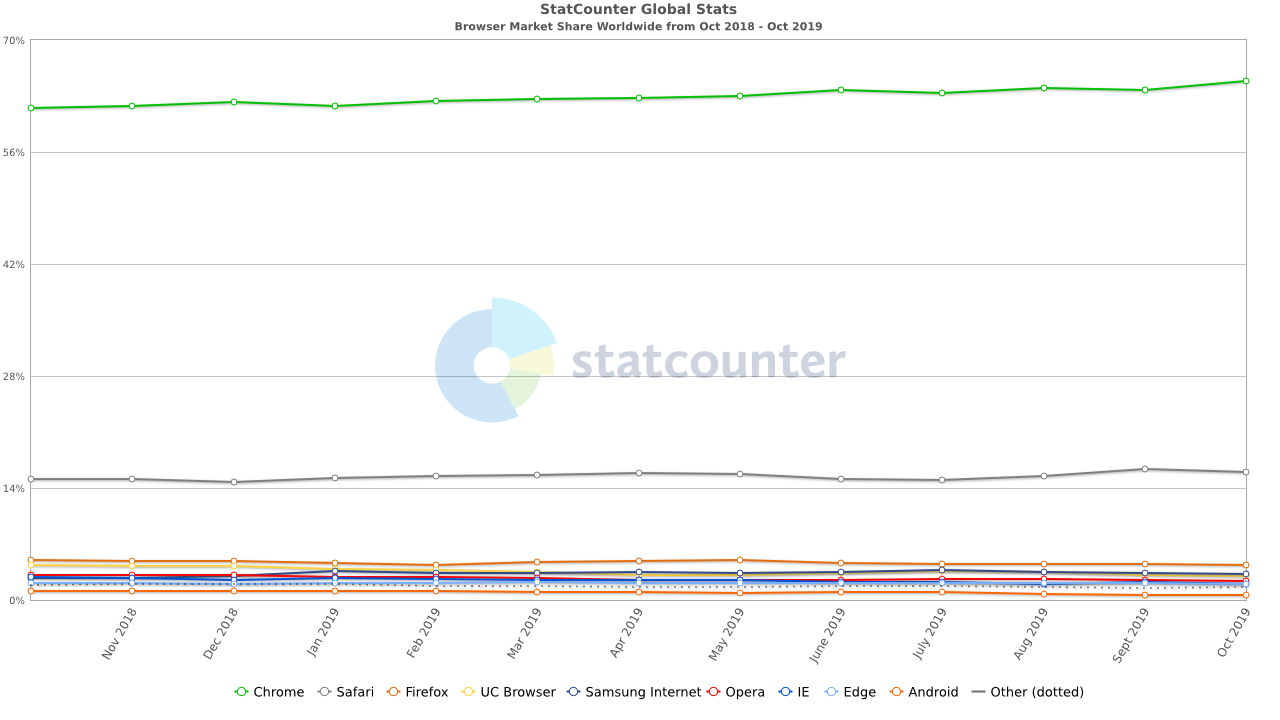

The ISPs’ business interests are obvious. But what’s driving the camp pushing for rapid DoH adoption? Why do Google and Mozilla employees keep stressing that it’s only an experiment, that if the UK needs to shield users from pornography those users won’t be included in the trial, and that they simply want to give users—including people in countries with heavy-handed internet controls—more privacy and security?

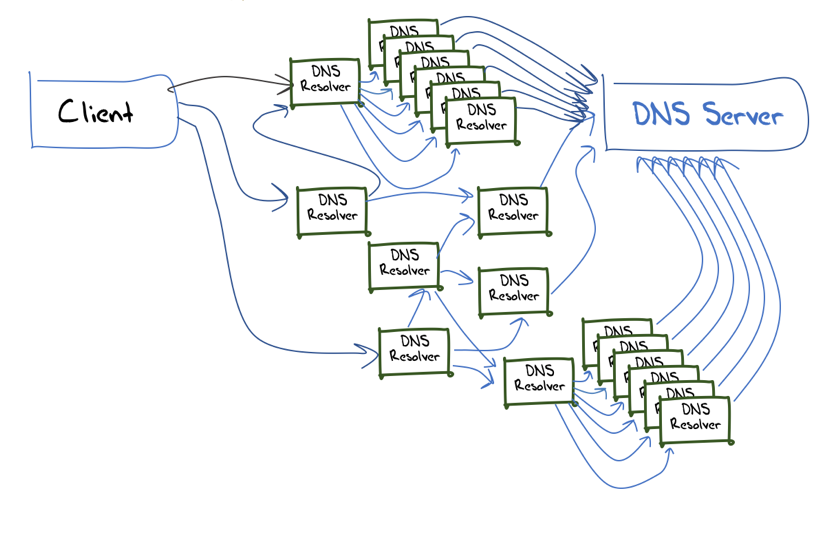

Some experts think the crux of the issue is DoH-capable DNS resolvers. Both Google and Mozilla say their browsers will use a list of such resolvers, but in practice Google operates its own DNS service, while Mozilla is developing its approach in close partnership with Cloudflare. Cloudflare also runs its own public DNS.

Add to that the fact that Chrome is currently the most popular browser, and the picture isn’t pretty. In a distributed, decentralized DNS system, you’d suddenly have a massive chunk under Google’s control and a smaller slice owned by Cloudflare. Nothing personal, dear ISPs—just business. The data that used to be yours is now ours.

Mozilla states in its DoH deployment FAQ that Cloudflare’s DNS resolver was not chosen because Cloudflare paid for it. Mozilla and Cloudflare both say they have no intention of monetizing the data that passes through their servers and are focused solely on improving privacy and the security of using the internet.

By corporate standards, Cloudflare at least looks somewhat like a genuine ally in this fight — the company has repeatedly affirmed its commitment to internet freedom, net neutrality, and free speech, and in its case those statements bolster its image as a key player in the fast-growing market for digital privacy and security. Google, however, looks far more suspect.

warning

One important reminder: no single technology can make you absolutely safe online. This article addresses DNS security only. That doesn’t replace the need to secure other protocols and ways you use the internet. The worst enemy of security is the belief that you’ve done enough.

Google is rapidly moving to monopolize key internet services, and some are already effectively monopolized. Beyond the economic and political angles, there are purely technical ones. Decentralization is intentionally built into internet protocols—the modern internet grew out of a U.S. military project whose goals included maintaining communications between participants after nuclear strikes. If a disaster physically wipes out part of the data centers, servers, or communication links, the internet is supposed to survive it.

But if a handful of companies start exclusively providing critical functions, what happens if one of them goes bankrupt? These are, of course, largely philosophical questions, but they’re worth considering. For example, staff at the Asia-Pacific Network Information Centre (APNIC) believe that the rollout of DoH is grounds for serious research into the degree of DNS centralization, and they intend to monitor the process closely.

Conclusions

Let’s recap. We’ll start with what we can say with absolute confidence.

DNS-over-HTTPS (DoH) will make life harder for anyone who wants or is required to monitor users’ DNS traffic. That includes ISPs, system administrators, developers and operators of firewalls and content filters, and government internet oversight agencies.

How much will DoH complicate things for them? No one can say for sure—it depends on the pace of adoption and the maturity of the technical solutions.

Does the Internet actually need this technology? It’s a hard question. Experts agree that DNS security needs to be improved, but they disagree on how—and many lament that new solutions are being developed too hastily, are deployed with difficulty, and ultimately overcomplicate the technical architecture to the point that even professionals struggle to make sense of it.

Do you personally need DoH? As with many things, it comes down to which threat you consider the bigger priority. If you’re worried about ISPs doing things you don’t like, or about content filters you didn’t ask for (e.g., government-mandated), then this might be another useful tool in your kit. If you’re more concerned about adversaries, or you need to make sure certain users don’t visit places they shouldn’t, then you should take a hard look at how DNS over HTTPS will interact with your specific requirements.

“Why do I even need any of this? I’ve got a solid proxy and Tor as a backup,” you might say. If so, then you really don’t need it. But not needing it doesn’t mean it isn’t interesting. For better or worse, the internet is shared with billions of everyday non-experts, residents of corporate networks, the quiet, unseen devices of network infrastructure, and the trendy denizens of the Internet of Things. And everything described in this article could have a serious impact on them. Exactly how and with what consequences—no one knows yet.

And finally: Mozilla’s engineers claim that in some cases using DoH can significantly speed up DNS query processing. If they’re right, they’ll turn from “Internet villain of the year” into “Internet superheroes.” And, as stories about heroes and villains tend to say—stay tuned.