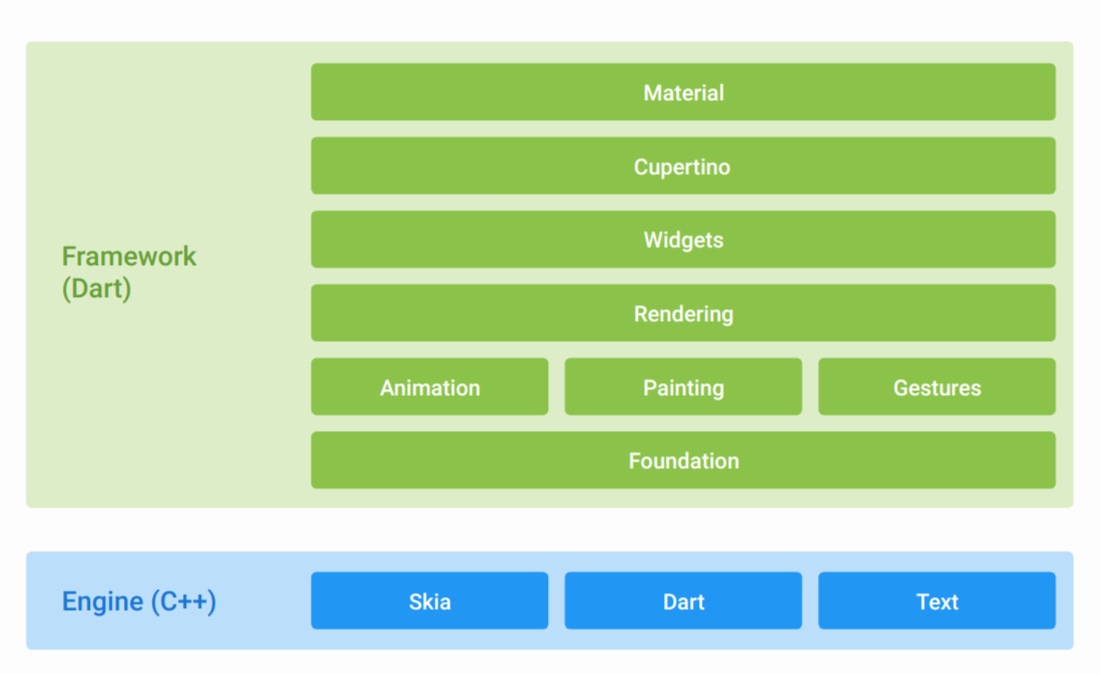

In Fuchsia, all apps are written in Dart, a language developed inside Google as a modern, high-performance alternative to JavaScript. Google has been working on Dart since 2011 and continually looks for ways to apply it, from the Dartium browser (a special Chromium build with Dart support) to compiling Dart to JavaScript. More recently, the company has promoted using Dart for mobile development via the Flutter framework, which lets you build Material Design–style interfaces for apps targeting Android and iOS from a single codebase.

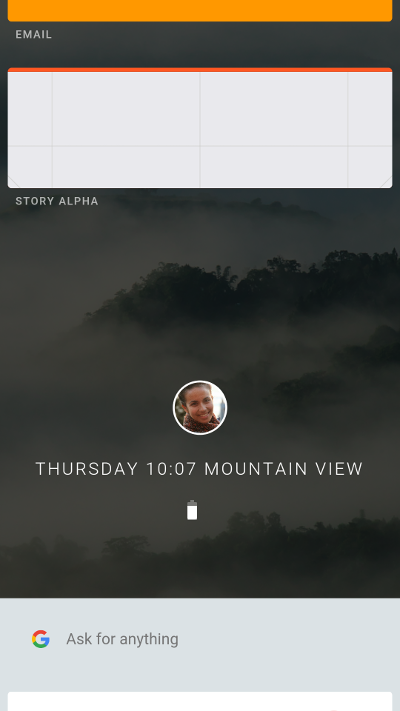

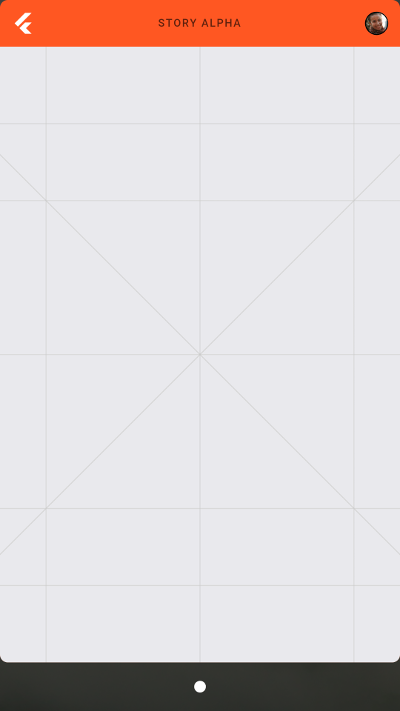

Fuchsia’s Armadillo user interface is built with Flutter. It’s a phone-first UI, optimized for portrait screens, with a quick settings panel and a vertically scrolling home screen. And because Armadillo is written in Dart and Flutter, you can already try it today. Enthusiasts have put together an Armadillo build as an APK you can install on any Google phone.

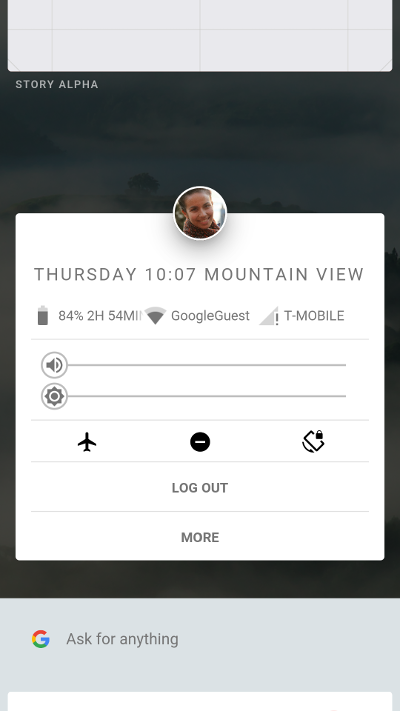

Just launch the app to get a glimpse of the future of mobile interfaces as envisioned by the Fuchsia team. In the center you’ll see the current user’s profile picture, along with the time, location, and a battery icon. Tapping the avatar opens a quick settings panel that will look familiar to any Android user. The buttons respond and the sliders move, but they don’t actually do anything. The Log out and More items don’t work at all.

|

|

| Armadillo home screen and Quick Settings panel | |

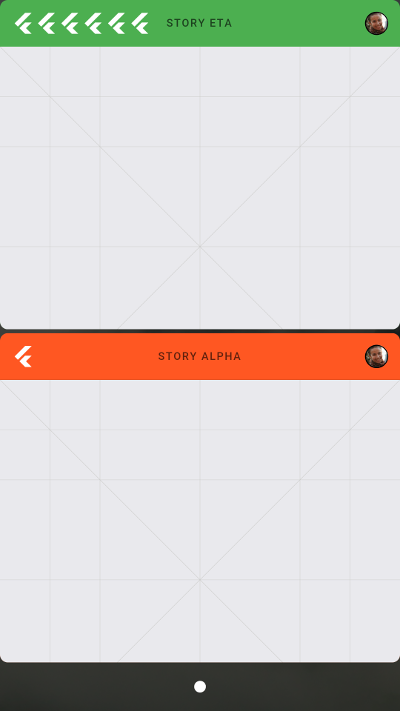

It gets more interesting when you scroll down: you’ll see a lot of placeholder cards. Each one expands to full screen when tapped. Note that at that moment a dot appears at the bottom, along with the time and battery status. In other words, the interface is dynamic—there’s no persistent status bar or navigation bar. They appear when needed and disappear when they’re not. The dot itself is, of course, the Home button; press and hold it to open the quick settings panel.

Unusual, interesting, but still fairly standard so far. The real magic starts when you try to combine cards by stacking one on top of another. In that case you’ve got two options: either split the window in two, or open two full‑screen windows with a tab strip along the top. You can keep adding apps and slicing up the screen almost indefinitely (at least until Armadillo crashes).

|

|

| Full-screen window and split-screen mode | |

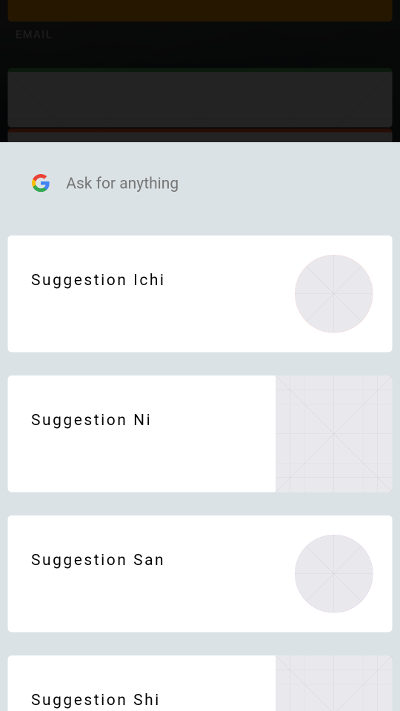

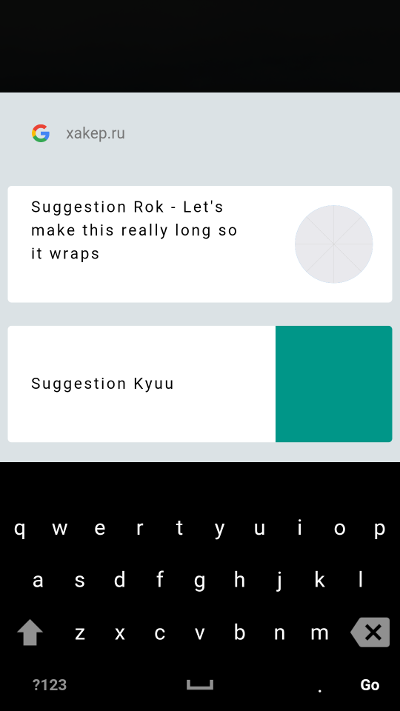

At the bottom of the home screen is a Google Now–style panel you can use for search; tapping a card expands it to full screen.

|

|

| Built-in Google Now and on-screen keyboard | |

From what we can tell, the goal of the Armadillo interface is to unify all information streams—notifications, widgets, Google Now cards, app windows, and the app switcher—into a single, coherent model and eliminate the current fragmentation.

It’s easy to see that Armadillo’s interface essentially revolves around two elements: cards and windows. Most likely, notifications will appear on screen as cards, and those cards will simultaneously serve as notifications, widgets, and thumbnails of the running app.

For example, you launch Telegram and minimize it into a card (which shows a couple of the latest messages, say). As notifications from other apps arrive and the user opens new apps and does other things, the Telegram card gets pushed up the stack; but as soon as a Telegram notification comes in, it jumps back to the top (or bottom, depending on the layout) and refreshes its contents. You can swipe the card away to close Telegram—or do nothing, and it’ll slide up out of view on its own.

These are, of course, just my own guesses, but the idea seems entirely sound, and a proper implementation would be genuinely convenient. The concept of apps collapsing into widgets has already been tried successfully and proven useful in BlackBerry 10 and Sailfish OS. And if you tie it into notifications, it would be downright elegant—a unified interface for managing everything.

What’s the point of all this?

Okay, Google really is developing a new OS for smartphones and desktop PCs (yes, Armadillo can scale up to large screens, presenting an interface in the style of a tiling window manager). Even as a concept, it looks cool. But why?

Is Google really going to walk away from Android—its massive user base and vendor ecosystem—for an OS with an uncertain future? There are two possible answers to that.

First. Inside Google, experimental projects are constantly appearing and disappearing. Some make it to production (a recent example: the neural network–based Google Translate engine), while others never get past alpha. Fuchsia fits this model perfectly: if it finds a use on phones—great; if not, they’ll try it somewhere else. There’s a reason Fuchsia can scale from tiny microcontroller systems to powerful workstations.

Second. Google plans years into the future. Fuchsia could be the platform that doesn’t replace Android overnight but gradually edges it out of the market.

With a little imagination, you can picture a scenario like this: Google pushes Fuchsia forward, finishes the graphical interface, builds a basic suite of apps, and rolls out low-cost smartphones based on it in India for about $50 each.

New smartphones with the latest version of Fuchsia are gradually rolling out. The app ecosystem is expanding thanks to Flutter, as developers have already begun using it to build cross‑platform apps for Android and iOS.

Fuchsia is getting an Android app compatibility mode (you can even port the Android runtime to BlackBerry 10, which isn’t based on the Linux kernel), which means access to a huge catalog of existing apps.

Independent developers are starting to check out the new OS and build apps for it, hoping to cash in if it takes off. Google is running competitions for the best apps in various categories, with substantial cash prizes.

Fuchsia is maturing and gaining capabilities, and companies are cautiously starting to release smartphones powered by it. The number of native apps is growing. Enterprise-focused features are beginning to appear.

The new OS is drawing praise rather than criticism. With it, Google has addressed many of Android’s pain points: updates arrive promptly straight from Google, there are very few security holes, and Fuchsia runs incredibly smoothly (its graphics stack is built on Vulkan, and Flutter can render at 120 frames per second).

More and more vendors are releasing Fuchsia-based smartphones, including flagship models. The native app store already lists 100,000 apps, and the Coding section of the magazine «Хакер» is now one-third articles about writing apps for Fuchsia.

Samsung says its Galaxy S16 will run on Fuchsia. Android is declared dead.

Sound far-fetched? Maybe—but that’s roughly the path Android took before it became the most popular OS in the world.