This is a column of disappointment, so I won’t be listing MIUI’s strengths—plenty of people have done that already. Instead, I want to talk about what makes this firmware bad, and in some cases not just bad but flat-out unusable. And it’s not about getting used to it; it’s about the system’s inherent design quirks.

From China with Love

First things first: MIUI is a Xiaomi product, originally built for Xiaomi smartphones in China. What does that mean in practice? Since Google services are legally banned in China, MIUI is tightly integrated with Xiaomi’s own ecosystem and other Chinese providers. That’s all well and good, except many of those services aren’t really intended for use outside China.

As a result, even after switching the firmware language to English or Russian, you’ll keep running into quirky issues. For example, the theme store is entirely in Chinese—which makes sense, since the themes are uploaded by Chinese users with Chinese descriptions. The local music and video stores are also in Chinese, so good luck finding anything. You’ll see Chinese text in the browser, the dialer (contacts), and even in the weather widget. And none of these apps can be disabled.

|

|

| Browser and caller ID directory | |

Google services and the Play Store are absent from the firmware only in the local Chinese builds. Global MIUI builds shipped on Xiaomi smartphones for export include Google services and apps, are well localized (including Russian), and aren’t tied to “China-only” services.

The catch is that if you download a MIUI build from 4PDA or XDA for a phone from another manufacturer, it’s often the Chinese version of the firmware. You’ll have to install Google services and the Play Store yourself (using a dedicated MIUI tool or the Open GApps app), and there’s no guarantee they’ll actually work.

If you order a Xiaomi smartphone from a Chinese online store, you might get a device with the Chinese firmware, with Google services preinstalled by the seller—often poorly. It’s also not uncommon to find a couple of trojans bundled in.

More ROMs, more variants

But MIUI firmware differs by more than just target market. The Chinese and Global builds are just the tip of the iceberg. You might also come across:

- a semi-official, Xiaomi-unsupported global MIUI build for Xiaomi phones, distributed via xiaomi.eu;

- the official Chinese MIUI firmware for phones from other manufacturers, available at en.miui.com/download.html;

- an unofficial Chinese MIUI firmware for phones from other manufacturers—oddly enough, also available there;

- an unofficial Russian MIUI build from miui.su, based on the Chinese version, with additional Russian localization, Google services, and the stock Chinese IME replaced by Google Keyboard (Gboard);

- an unofficial Chinese MIUI build created with PatchROM. You can find these on forums. It’s essentially your device’s stock ROM patched to look and behave like MIUI, with MIUI system apps added (while keeping the remaining stock apps).

But that’s not all. It’s not just the firmware’s regional targeting and the download source that matter; the version does too—and not in the same way Android version numbers matter. For example, at the time of writing the current MIUI branch is 8.3, build 7.3.30, while the underlying Android version varies: Android 7.0 for the Xiaomi Mi4S, Android 6.0 for the Mi5S, and Android 4.4 for the Redmi 1S.

How about that? To untangle this a bit: 7.3.30 isn’t really a version number—it’s a build date. And yes, the firmware looks and behaves the same regardless of the underlying Android version. However, if an app requires Android 6.0, you’ll be able to install it on a Mi5S but not on a Redmi 1S—even with the same MIUI version.

Hacks and workarounds are the name of the game

Alright, let’s talk about something more down to earth—the interface. Without a doubt, it’s one of the OS’s best features. MIUI is slick, feature-rich, and nothing like stock Android. Nearly every visual element has been reworked—some ideas are borrowed from iOS and Samsung’s TouchWiz, while others showcase the designers’ own vision.

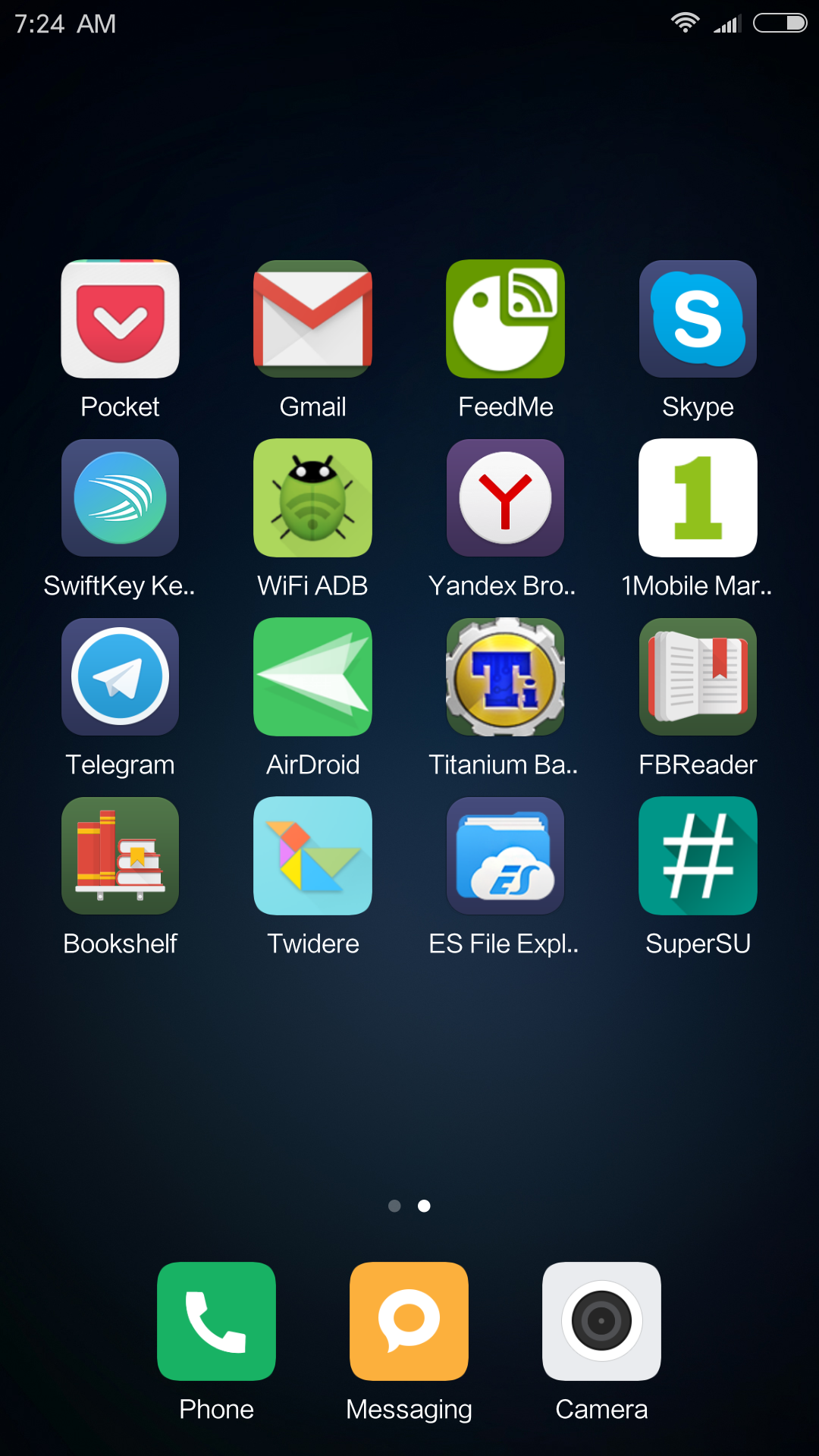

But there are problems with all this “beauty” (or lack thereof, depending on your taste). The first thing you’ll notice when using MIUI is the app icons. They’re clearly modeled after Apple’s guidelines: rounded squares, uniform size, simple lines and shapes, bright colors. At first glance, it looks nice.

On a second look, you start noticing the problems. MIUI doesn’t use dedicated icons for third-party apps; instead, it either shrinks the original icon and drops it into a rounded square—tinting that square in various colors based on a not-quite-clear algorithm—or it scales the icon up and rounds its corners. The result is a handful of well-crafted stock app icons alongside a bunch of third-party icons shoved into multicolored squares (some of them green) or cropped at the edges.

| Sleek stock app icons vs colorful chaos from third‑party apps | |

Second: MIUI borrowed iOS’s idea of “live icons” (the calendar and clock show the actual date and time) and added badges—notification counters next to the app icon. As a result, notification icons in the status bar became redundant, so the developers removed them. You can try to bring the icons back, but they don’t fit the redesigned status bar at all—especially the stock app icons.

And for dessert: MIUI’s signature UI elements are used only by the preinstalled apps. Everything else runs with the stock Android look—Material for modern, supported apps, Holo for legacy apps, and the Android 2.3 style for the really ancient ones. Beautiful, isn’t it?

More App Permissions!

One very odd quirk of MIUI is its app permissions system. As we all know, Android 6.0 introduced runtime permissions, which let users control which phone features an app can access and which it can’t. It’s implemented much like in iOS, via on-screen permission prompts.

Starting with Android 6.0, all permissions are grouped into seven categories (camera, microphone, contacts, and so on), which helps cut down on prompt spam: even if an app wants access to everything possible, you’ll have to tap “Allow” no more than seven times.

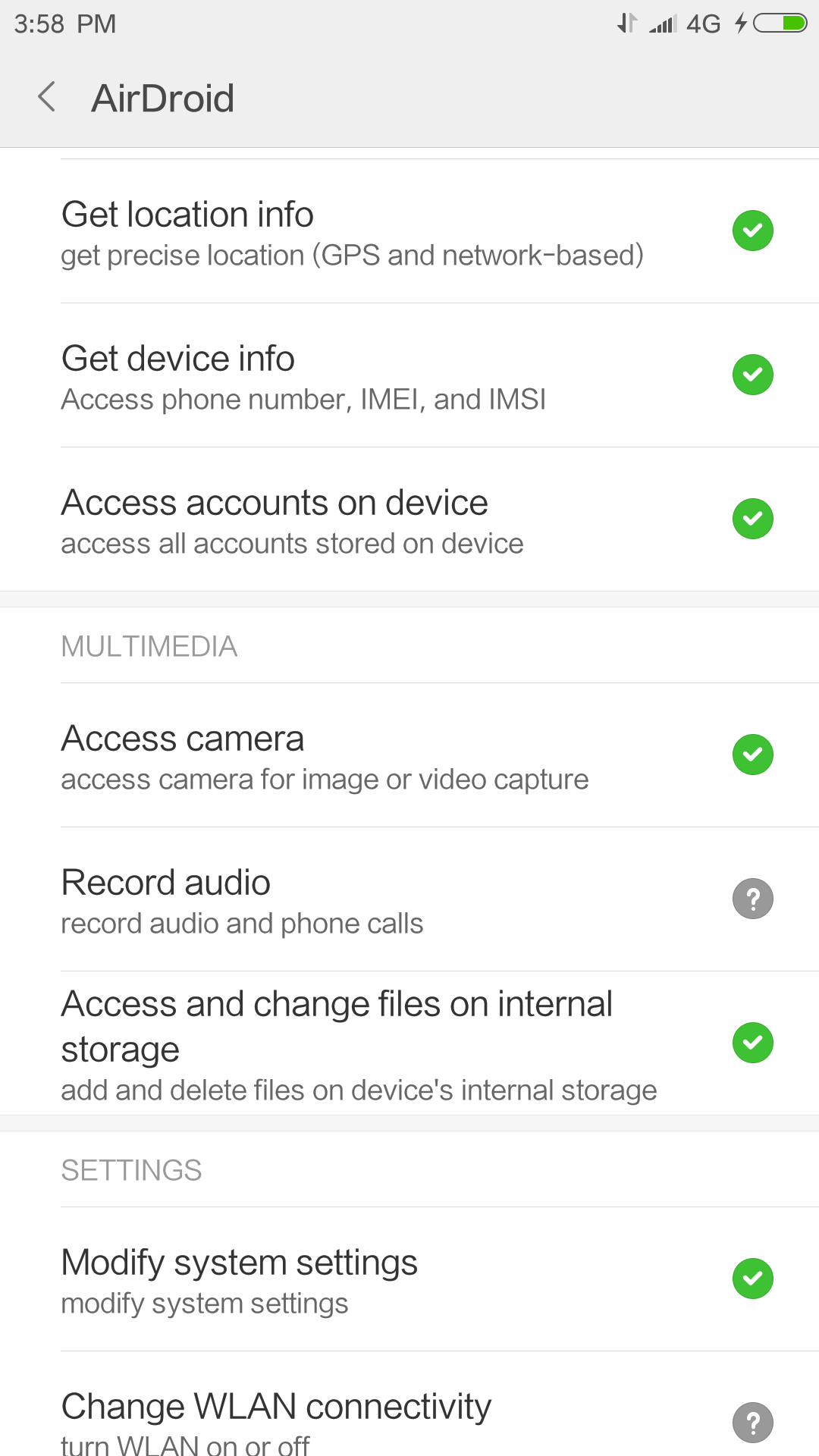

MIUI’s developers built their own permission system even before Android 6.0, and it works in a rather unconventional way. For example, if you install Telegram, you’ll only see permission prompts three times: twice on first launch (to read and modify contacts) and once more when you try to send a photo (camera access). That might seem fine, except Telegram can also record audio, access your location, and save files to the memory card without any further prompts or bothering the user.

The situation gets even more interesting if you try to run an app that wasn’t designed for Android 6.0—meaning it can run on 6.0, but was built targeting an earlier version. Stock Android doesn’t apply the runtime permission system to such apps (to avoid breaking them), but MIUI handles this differently.

For example, take AirDroid. Right after installation, AirDroid already has access to things like location data, the IMEI, all user accounts on the device, the camera, the SD card, and it can even modify system settings. However, you still have to explicitly grant it permission to read your call history, SMS, and contacts.

While using other apps, you’ll occasionally get prompts asking for permission to access the internet (and not always consistently) or, for example, to allow installing apps over USB—and the “Don’t ask again” checkbox may not even work. MIUI also includes many other types of permissions you’ll never encounter in stock Android.

|

|

| AirDroid’s permissions right after installation, and an internet-access prompt in the Weather summary. | |

Bottom line: MIUI does have a permissions system, but it behaves unpredictably and is completely incompatible with Android 6.0’s model. Some permissions you have to approve yourself, others the system grants automatically, and there’s no separation between apps that support runtime permission requests and those that don’t.

Just Say No to Background Activity

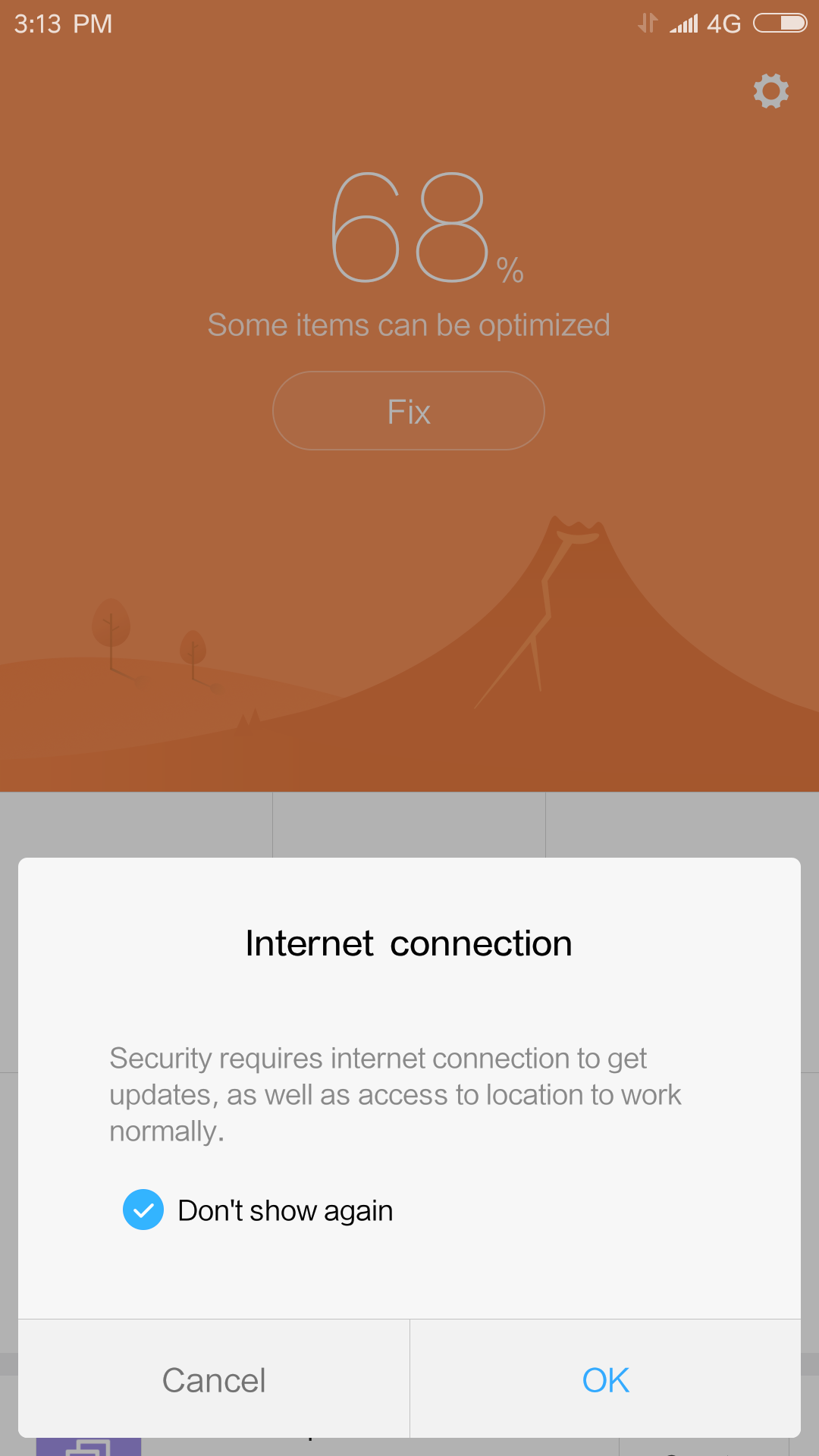

And finally, the juiciest part: the ban on resurrecting background services is a headache for thousands of users and app developers. In short, on Android any app can start a Service that continues running in the background even when the app itself is minimized or evicted from memory. A Service can be started with START_STICKY, which makes it quasi-immortal: even if the memory reclaimer or a task killer terminates it, the system will immediately restart the service.

Many apps rely on background services, including some messengers; smartphone anti-theft tools, email clients, and cloud sync systems use them as well. A background service is a common solution when an app needs to stay running in the background and, for example, wait for data from a server. Services can also be triggered by external events, such as the arrival of a push notification or system boot. MIUI breaks this model by preventing services from restarting. As a result, users often miss notifications for incoming emails, messages, and reminders.

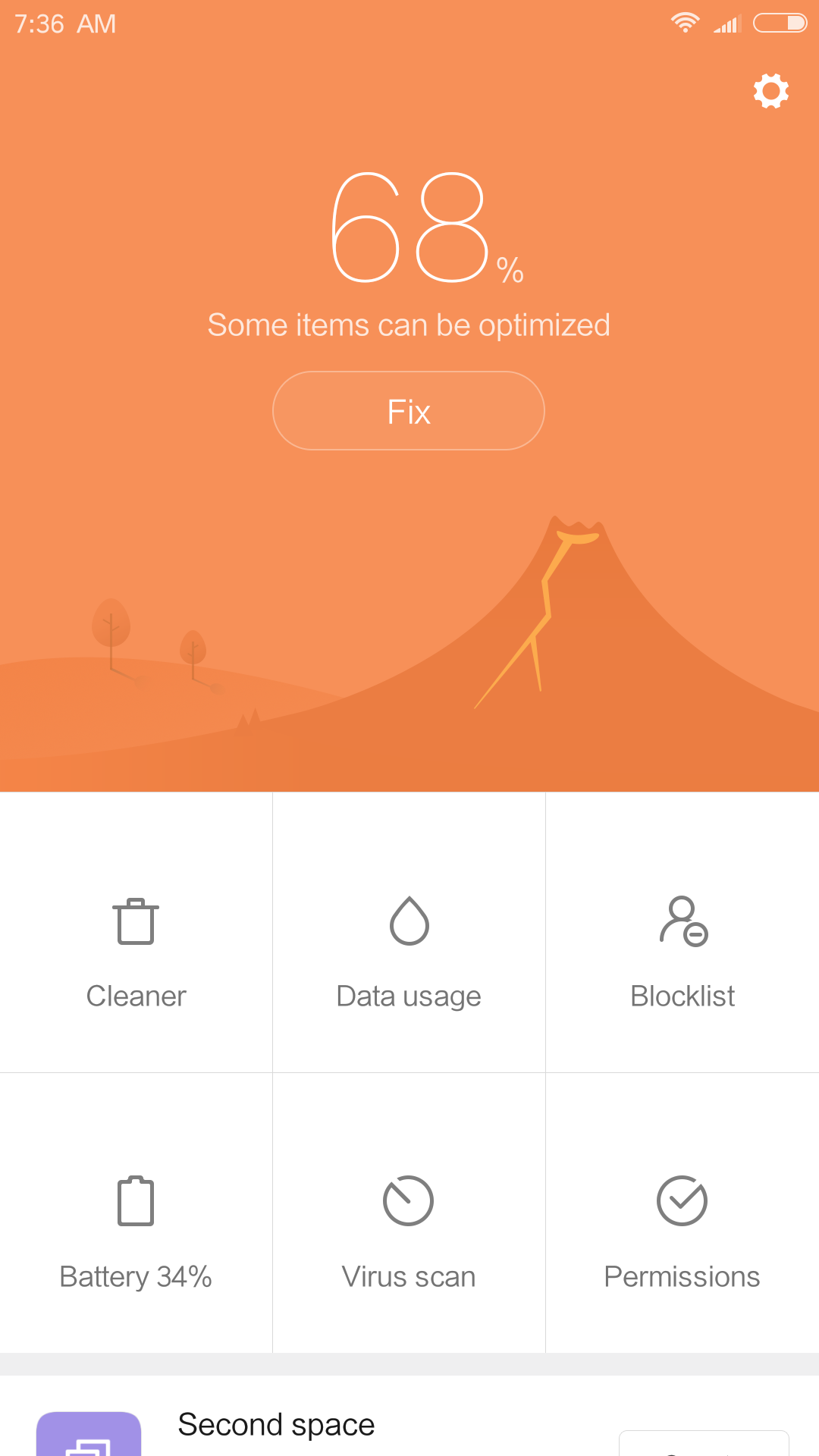

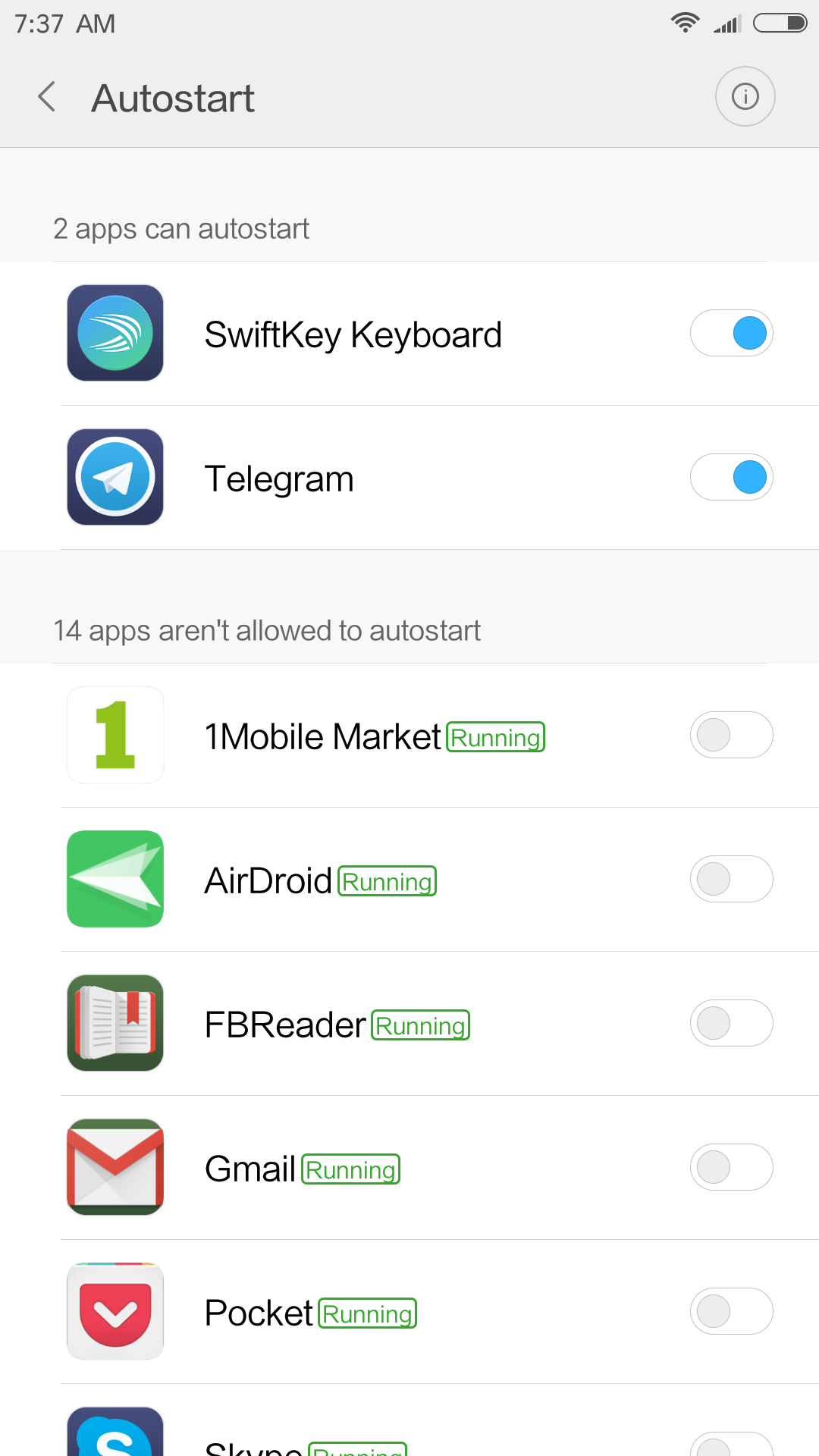

It’s a real problem, and at first glance it might seem odd that MIUI’s developers didn’t include a way to disable this system. But they did! Guess where the toggle lives? Right here: “Security → Permissions → Autostart.” How about that? Easy to guess what this settings section is really for?

|

|

| You can disable the background‑service launch blocker in the Security app: Permissions → Autostart. | |

But that’s not all. You can’t just flip a switch to disable the policy that blocks service restarts—you have to do it per app, and you’ll need to repeat it for every newly installed app. And if you’ve never done this and your notifications have always been fine, you’re probably using the Global ROM—just one example of MIUI’s fragmentation.

And yes, I’ll address the objection from those who’ll say this exact feature—even stricter—already showed up in Android O. Here’s my answer: in Android O, the restriction on running background services applies only to apps that target Android O, i.e., those that have been migrated to JobScheduler and will therefore behave correctly. All existing apps already written and published on the Play Store will continue to work as before.

Conclusions

I have no intention of starting a flame war. MIUI is quite usable, and many people consider it more convenient than LineageOS, for that matter. The purpose of this column is simply to inform those who want to install MIUI or buy the Chinese version of a Xiaomi phone about what they might encounter. Personally, I find MIUI awkward, feature-bloated, and too unpredictable.