Once more, slowly: the entire multilayered security stack—every extra check, backup passwords, and even iCloud Activation Lock—now hinges entirely on the device’s passcode and can be easily reset if that passcode is known.

Really? Let’s break it down.

warning

All information is provided for informational purposes only. Neither the editorial team nor the author accepts responsibility for any damage that may result from the use of the materials in this article.

Password-Protected Backups

Imagine you work at a company whose core business is cracking passwords. iPhone backups—those you can create on a computer using iTunes or third‑party tools—can be encrypted with a password, and the protection is pretty robust: to brute‑force it successfully, you need a machine with a powerful GPU. Then the arms race begins: Apple keeps hardening the protection, and you keep building ever more advanced cracking algorithms. In the latest round, Apple seems to have the upper hand: even a rig packed to the gills with GPUs can’t try more than a few dozen (!) passwords per second.

Got the picture? Now here’s the kicker: Apple pulled a fast one, and in iOS 11 the iPhone backup password—which is painfully slow to brute-force—can simply be reset. Not on an existing backup, of course, but on the phone itself, and only if you know the device passcode—still, the backup password just gets reset!

How It Worked in iOS 8, 9, and 10

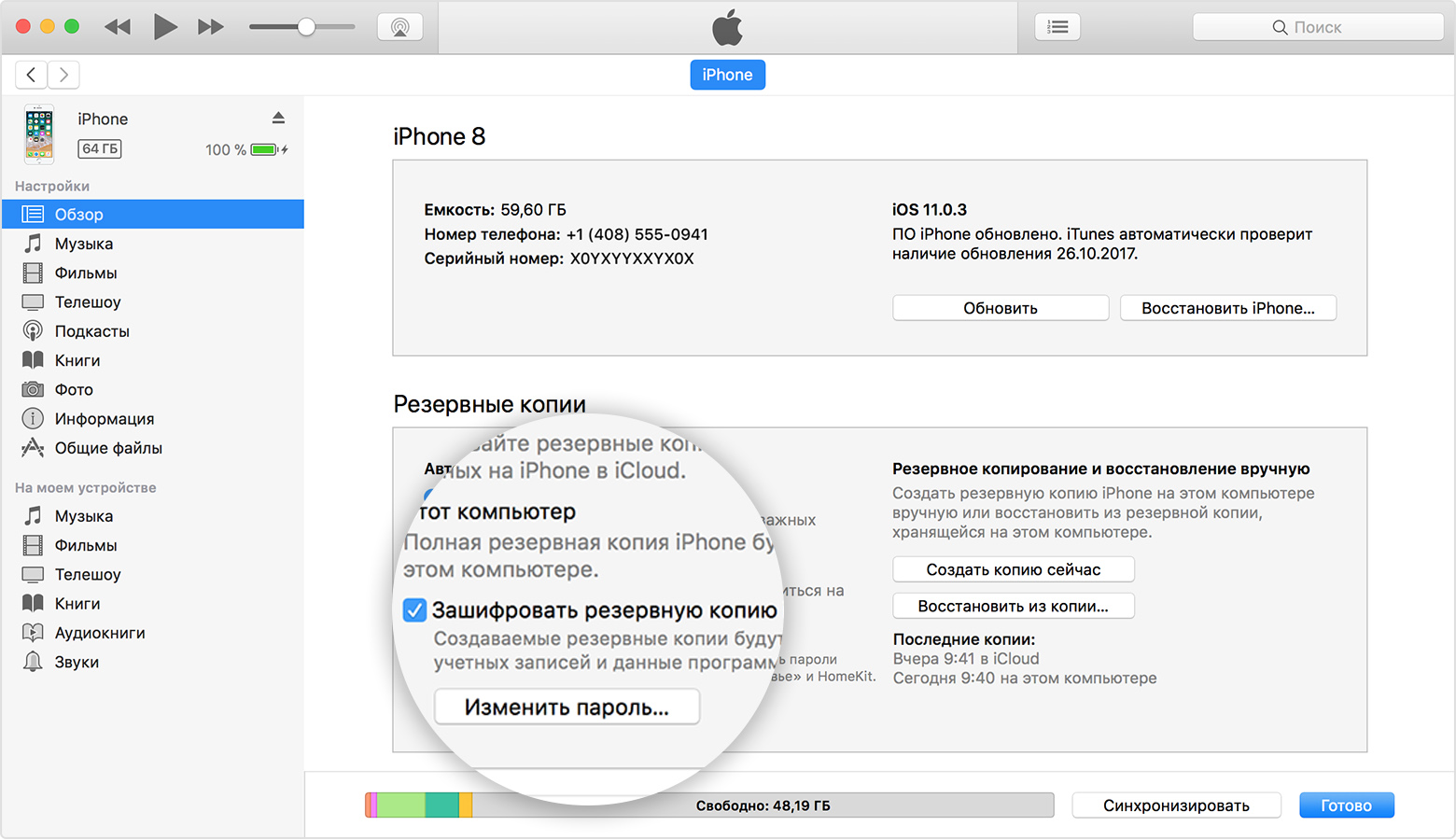

How did it work in iOS 10 and earlier? The backup password was set in iTunes.

Pay attention to the “Encrypt iPhone backup” option. If the box is checked, you can remove, reset, or change the backup password in iTunes only if you know the current password.

In iOS, the backup password isn’t an iTunes setting, nor is it a property of the backup itself—even though the backup is encrypted with that password. The backup password belongs to the device, the specific iPhone, and is stored deep within its system. Any attempt to reset or change the backup password—whether from the phone or through iTunes—must go through iOS. In iOS 8, 9, and 10, the only way to change or remove the backup password was to launch iTunes and enter the old password.

Forgot your backup password? Not surprising — you probably entered it only once, during initial setup ages ago. Want to reset the forgotten password? That’s only possible after wiping the phone and restoring it to factory settings. No, you can’t recover data from the encrypted backup — you don’t know the password. Yes, you can restore data from iCloud (including iCloud Keychain, which stores — or can store — all your passwords).

On the face of it, the system is logical and internally consistent, striking a good balance between security (if you don’t know the password, you can’t reset it) and convenience (you can still restore from a cloud backup even if you forgot the password). But users complained: “iTunes is asking for a password — I never set one!” The police complained, too. Corporate customers weren’t happy either. And Apple made concessions.

How it works in iOS 11

In iOS 11 you can still set a password for your iTunes backup, and you still can’t reset or change it through iTunes if you forget the old one. But—surprise!—now you can reset the backup password right on the device itself. Here’s what Apple says on the subject:

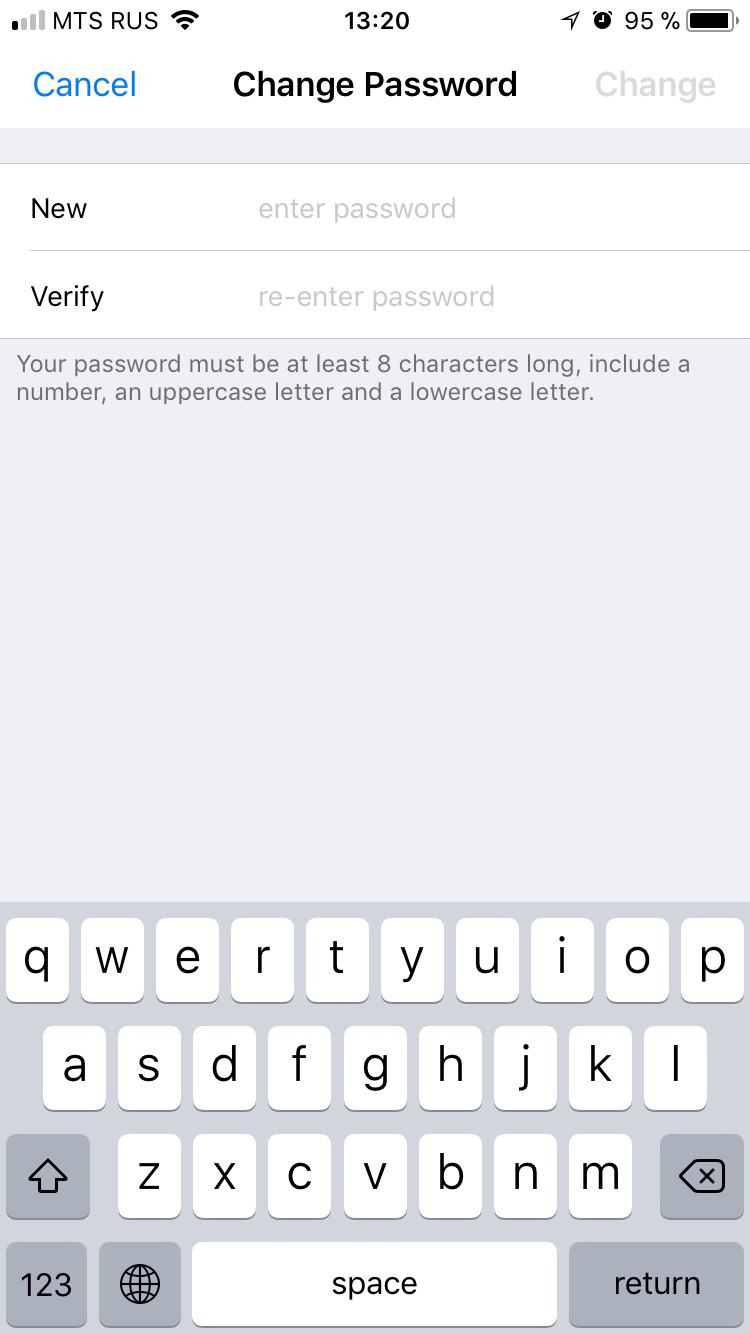

On iOS 11 and later, you can create an encrypted device backup by resetting the backup password. To do this, follow these steps.

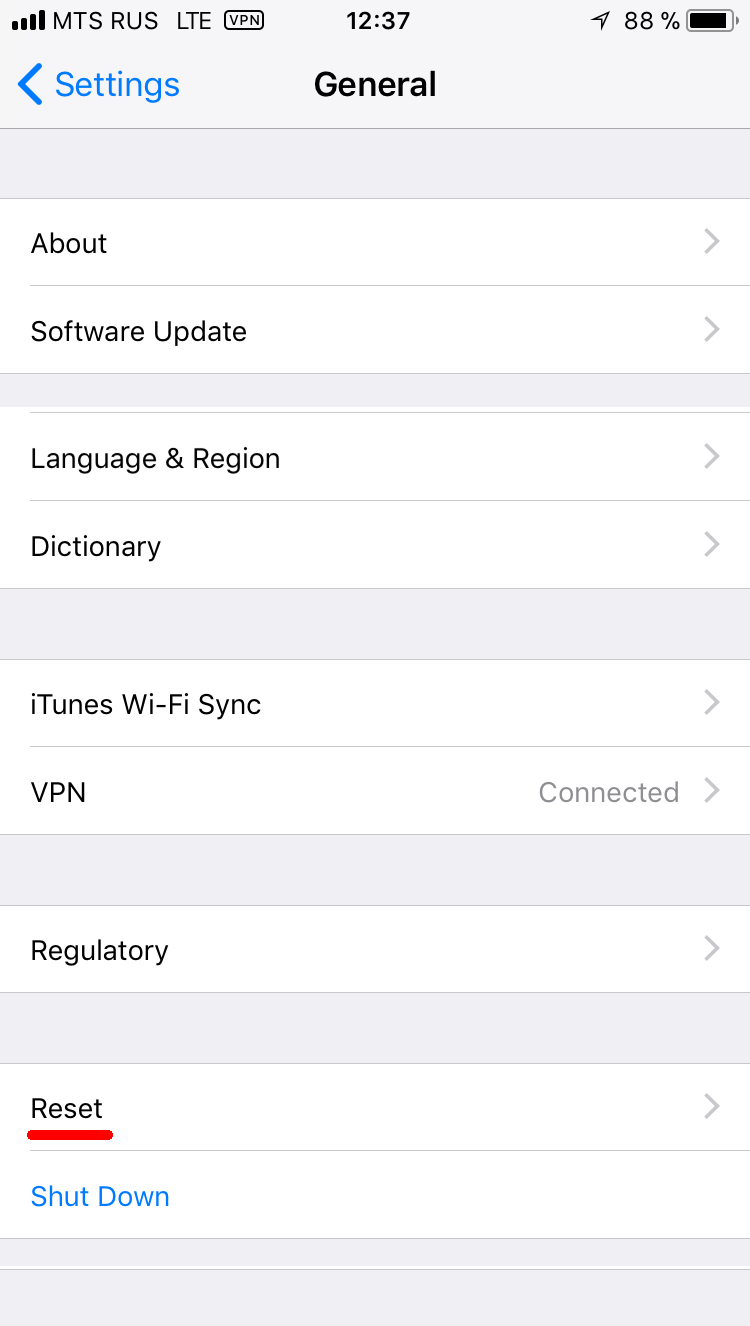

- On the iOS device, go to Settings > General > Reset.

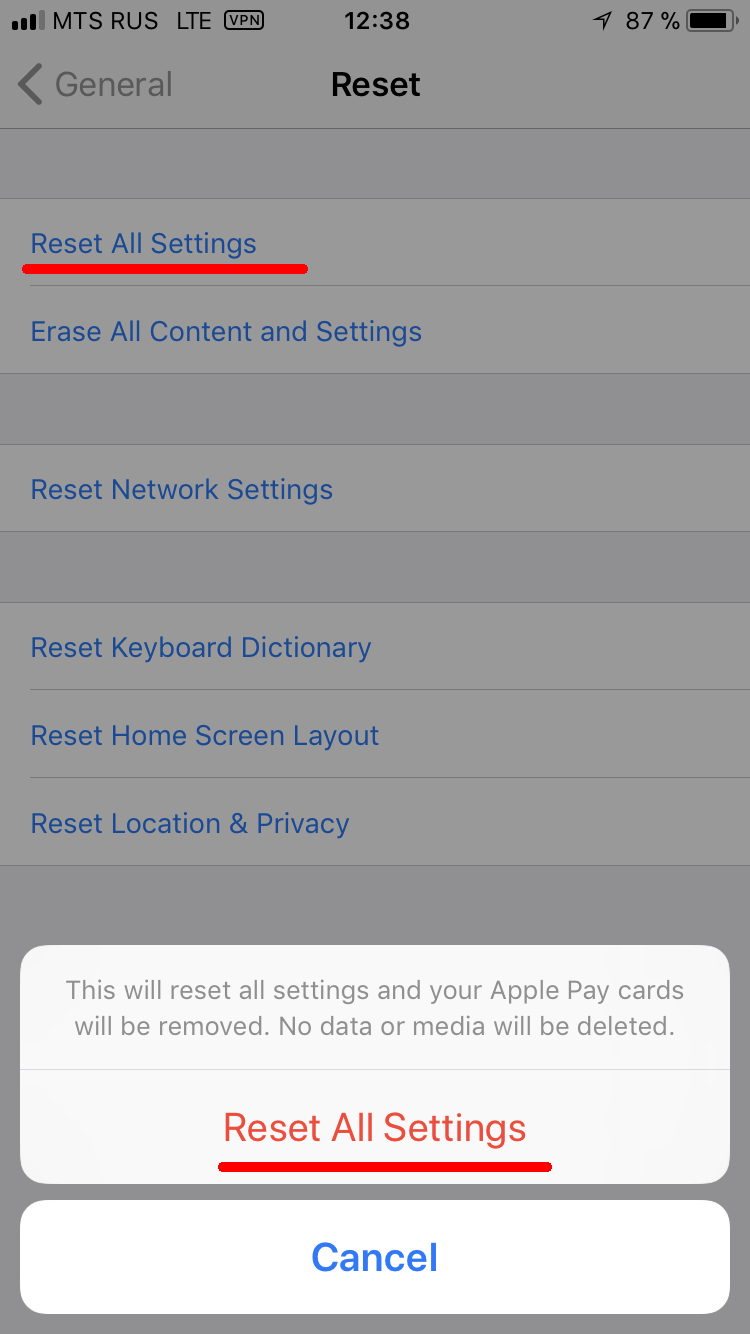

- Tap Reset All Settings and enter your iOS passcode.

- Follow the prompts. This won’t erase user data or saved passwords, but it will reset settings such as display brightness, Home screen layout, and wallpaper. The backup encryption password will also be cleared.

- Reconnect the device to iTunes and create an encrypted backup.

You won’t be able to use previously created encrypted backups, but you can create an iTunes backup of your current data and set a new password for it.

If the device is running iOS 10 or earlier, you can’t reset the passcode.

Essentially, we’re talking about these settings.

|

|

And that’s it. The iTunes backup password has been reset, and now you can create a new backup—or, more to the point, extract the data from the phone. Note: before creating a fresh iTunes backup, you’ll need to establish a trust relationship (pairing) with the computer, which requires entering the device’s lock passcode (which, per the scenario, you know).

You must set a new (known) backup password. Why? Without a password, app data in the backup will be left unencrypted, but the Keychain will be encrypted with the device’s hardware key, which you can’t extract from the phone. Set a backup password, and the Keychain—where all user passwords are stored, including the Apple ID password, authentication tokens, payment card numbers, and more—will be encrypted with that same password.

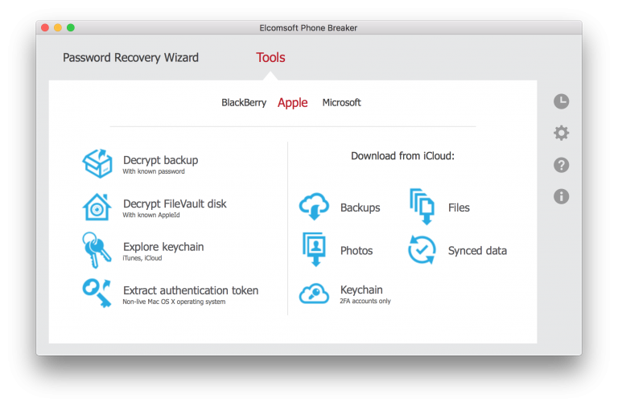

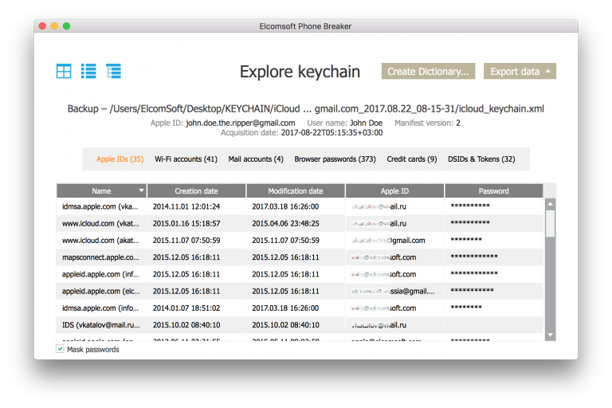

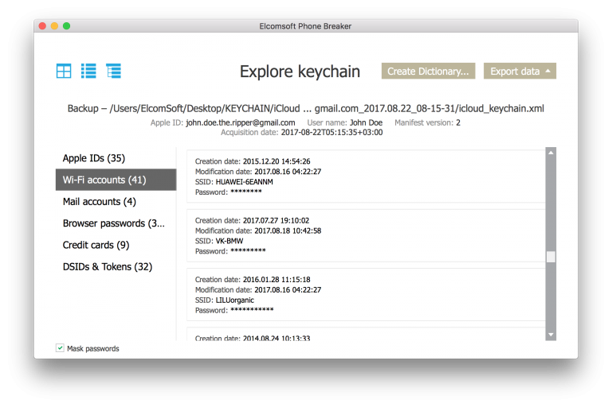

What’s next? Decrypt the backup (for example, using Elcomsoft Phone Breaker) and review its contents. Most likely, the main points of interest will be the user’s passwords and photos.

Look for the Google Account password. If it’s in the keychain, you can gain access (for example, using Elcomsoft Cloud Explorer) to a massive trove of user data: a detailed location history for the past several years, all passwords saved in the Chrome browser, bookmarks, search queries and browsing history, and much more. Two-factor authentication? In all likelihood, the iPhone in your hands can be used to approve the request via Google Prompt or, at the very least, to receive an SMS with a one-time code.

By the way, what do you do if your photos didn’t make it into the backup for some reason? Even data recovery specialists sometimes get stumped by this: the photos are clearly there—you can scroll through them on the phone—but they’re missing from the backup!

The answer is usually very simple. A few years ago, Apple introduced an iCloud-based service that lets users sync photos and videos through the cloud. If iCloud Photo Library is enabled on the iPhone, photos are stored in iCloud—not in iCloud backups, but in a dedicated area specifically for media. Moreover, if this setting is on, photos are also excluded from local backups created with iTunes. So to extract them, you can turn off photo syncing with iCloud in the iCloud settings and then create a fresh backup.

Strictly speaking, these steps aren’t really necessary—there are plenty of other ways to transfer photos and videos from an iPhone. But if you’re going to make a backup, make it a full one.

So, with nothing more than an iPhone and its known passcode, we’ve already gained access to the following data:

- Everything stored in the local iTunes backup (assuming you know the backup password)

- Passwords for all items stored in the local Keychain

- Photos and videos

- Application data (typically stored in SQLite)

That’s already a lot, but it gets even more interesting. What if I told you that now you can easily change the Apple ID password, unlink the phone from iCloud, and remotely lock all the user’s other devices—so completely that they won’t be able to do anything about it?

Changing Your Apple ID Password and Disabling Activation Lock

You probably know that to change the password for an online account—Apple, Google, Microsoft, whatever—you usually have to enter the current password or go through a reset that sends a message to the registered email address. On iOS, though, you can change the Apple ID password (i.e., the iCloud password) quickly and easily if you have the iPhone in hand and know its device passcode. You don’t need the old password; you don’t need to receive an email at the registered address, and you don’t need to open any reset links. The only caveat: this method is only guaranteed to work for accounts with two‑factor authentication enabled.

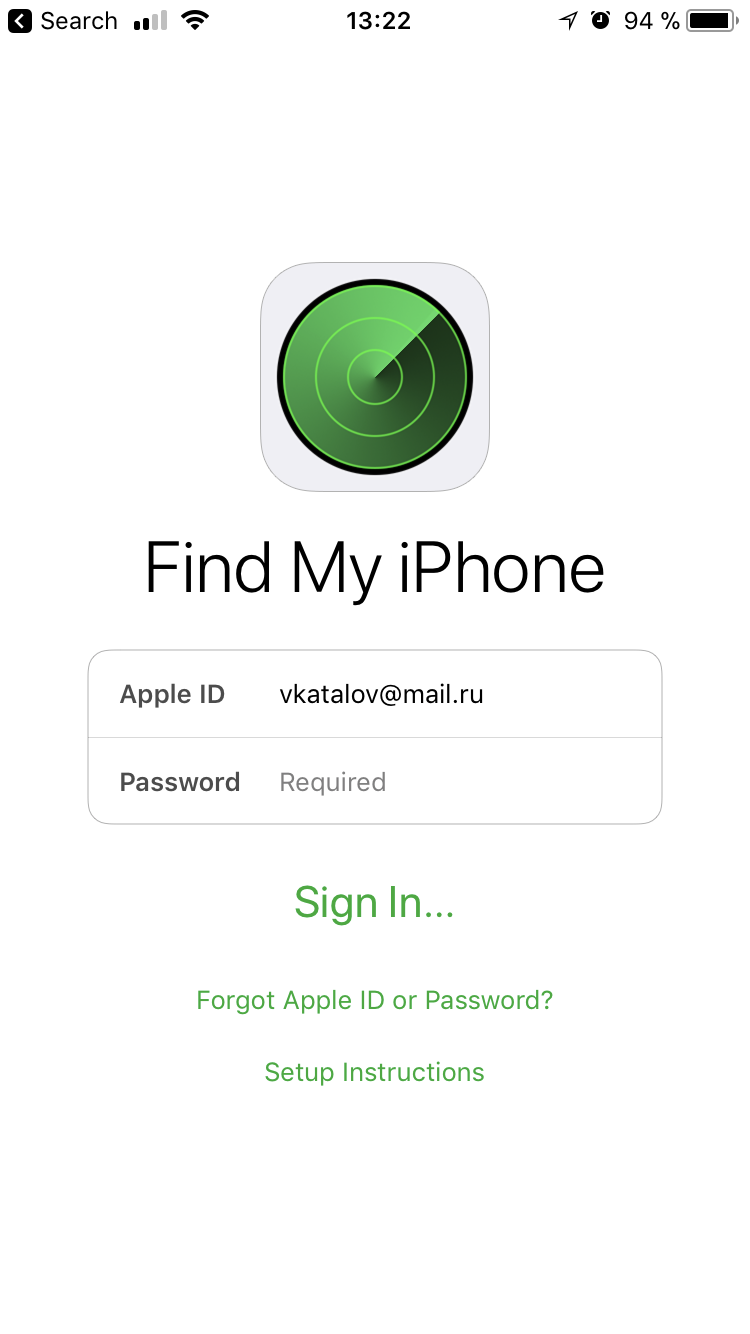

So you’ve got the iPhone in hand and you know its passcode. Open the built-in Find My iPhone app.

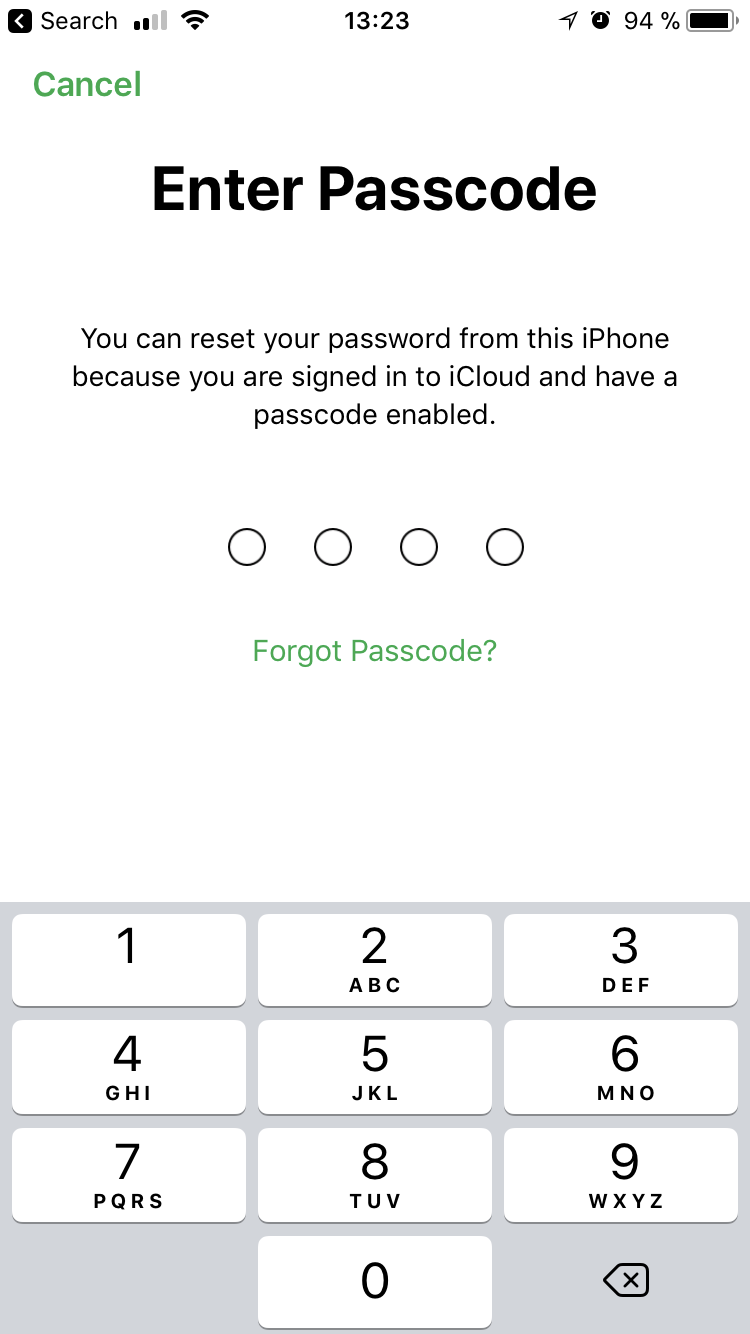

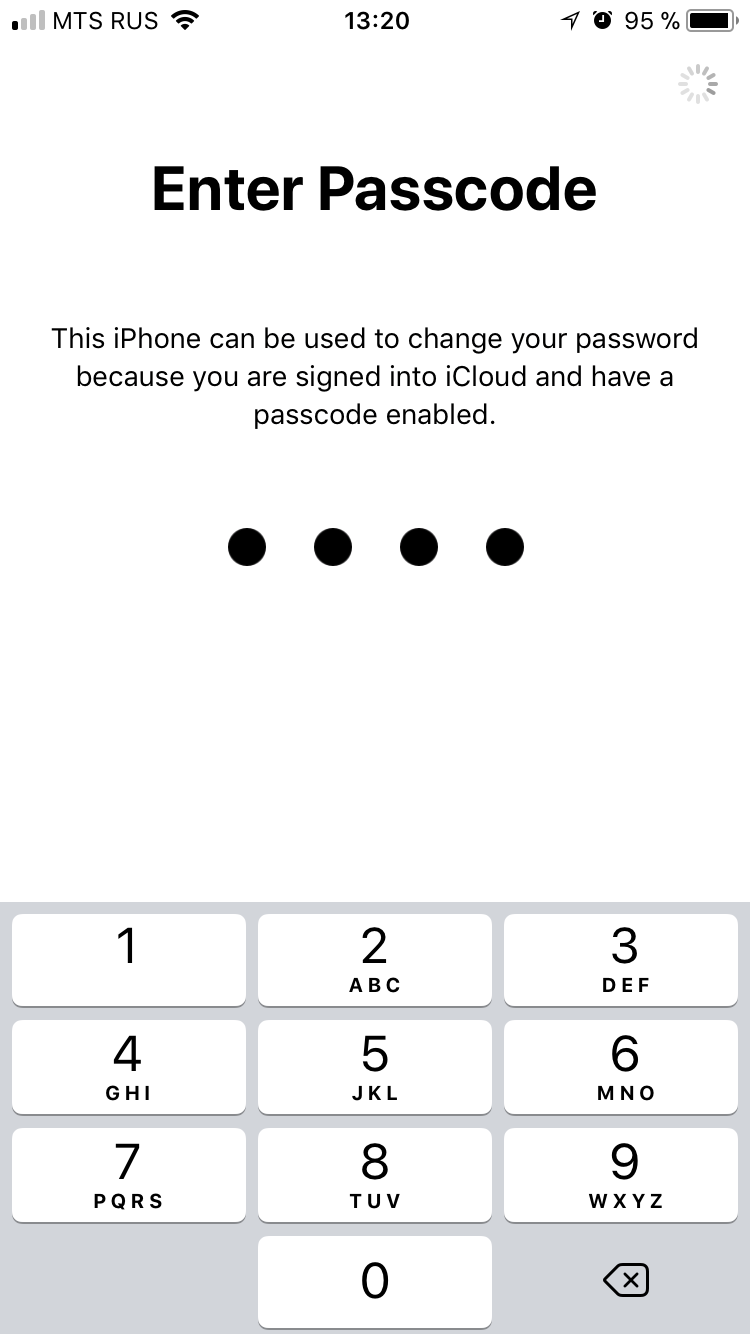

See that password field with the intimidating “Required” label? It’s not actually required. Just click “Forgot Apple ID or password?” and you’ll get a prompt for the phone’s lock screen passcode instead.

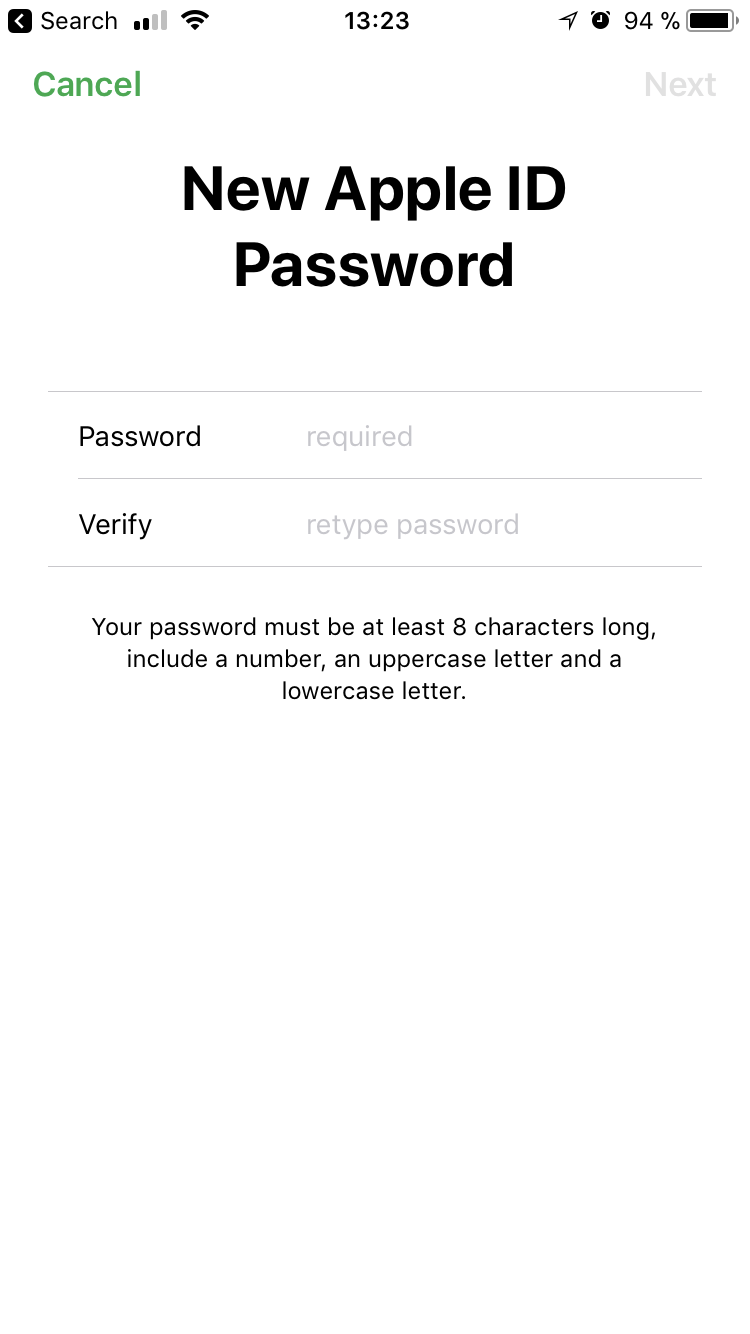

Enter your passcode, and on the next screen you’ll be able to set a new password for your Apple ID (which is the same as your iCloud password).

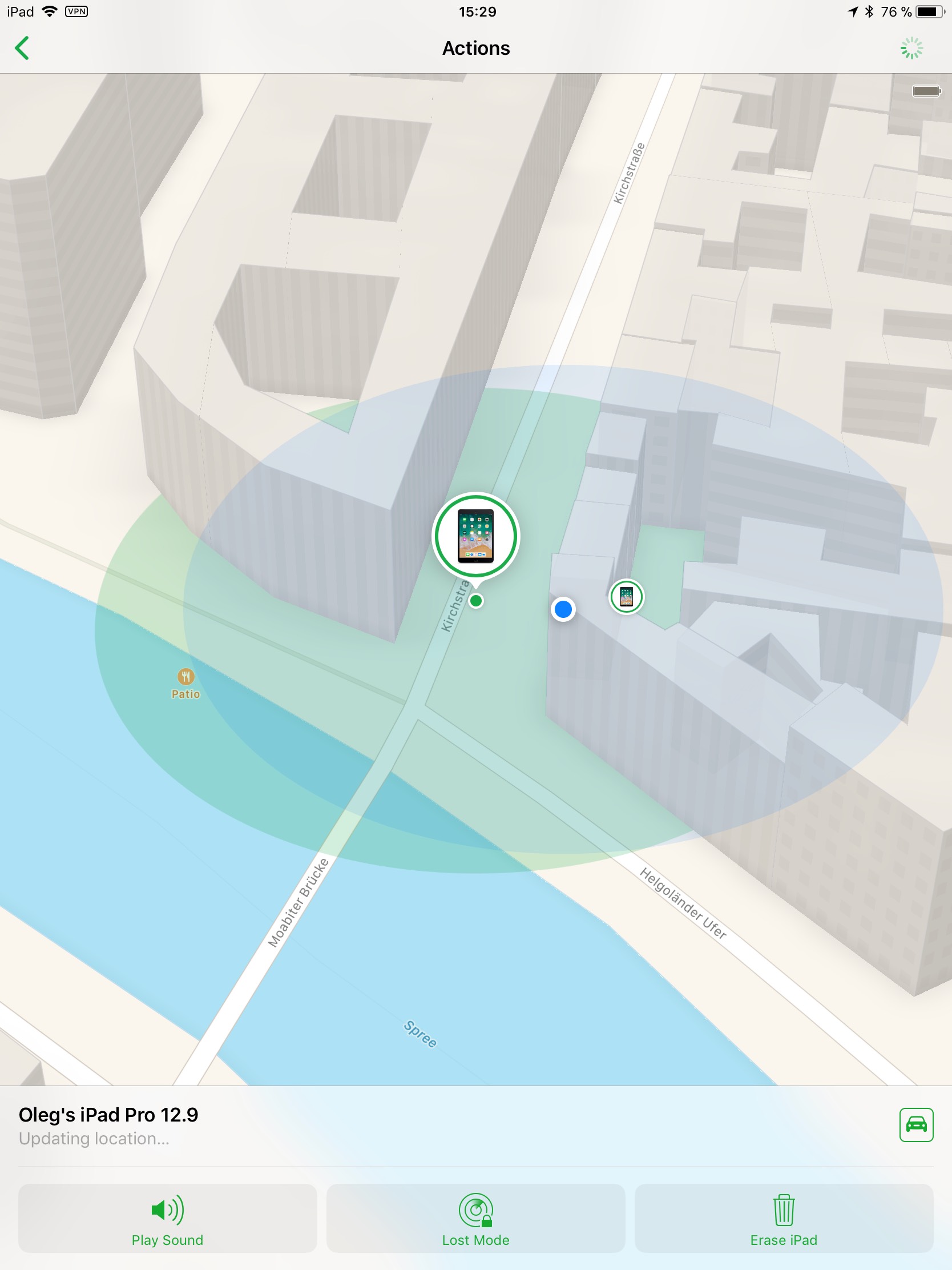

The job’s done: we’ve changed the Apple ID/iCloud password. Now you can easily disable Find My iPhone in Settings, and the former owner won’t be able to do anything with your device.

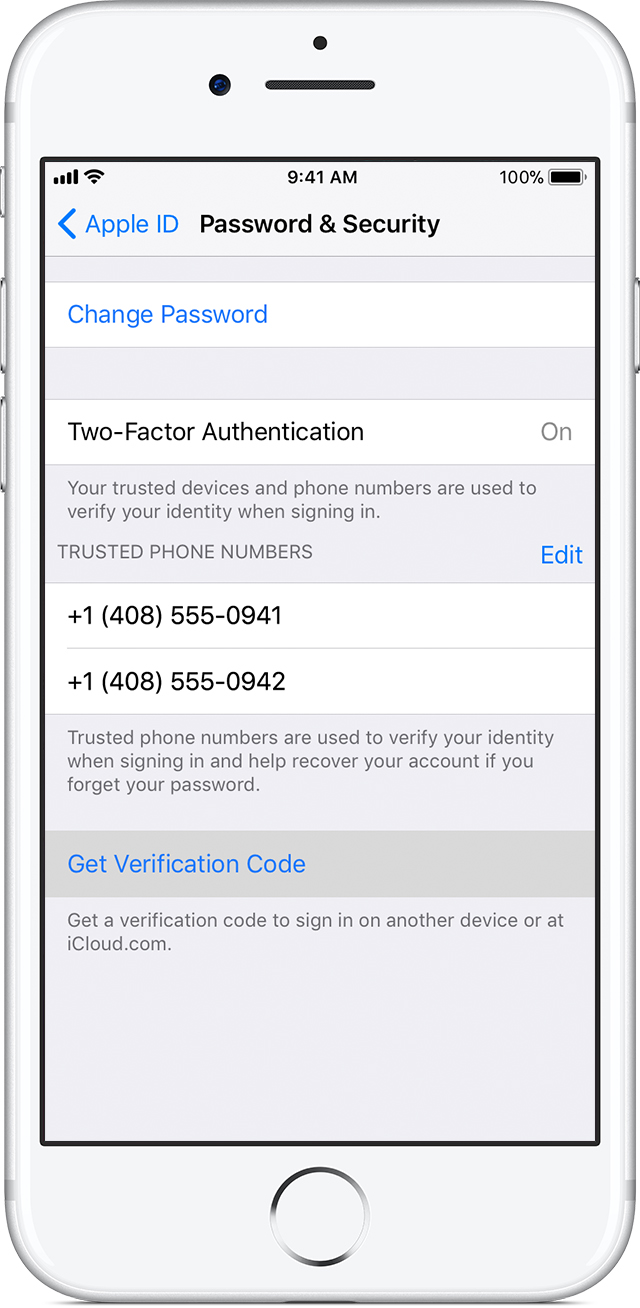

By the way, you can do the same another way, without using the Find My app. Just tap your Apple ID in the device’s Settings, then open Password & Security.

Next, tap Change Password. You’ll be prompted for the device lock password.

After that, you can safely change your iCloud/Apple ID password.

Back to step one: look at the Trusted Phone Number field. This is the number that will receive SMS codes for two-factor authentication. It’s also the number you can use to recover the account if an attacker changes the Apple ID password. However, if the attacker knows the device passcode, there’s no obstacle: first they add a new trusted phone number, then they remove the old one that belonged to the previous account owner. From that moment on, everything—lock, stock, and barrel—belongs to the new owner.

Do we really need to explain how to turn off Find My iPhone? It’s just a couple of taps in iCloud settings. To disable Activation Lock, you might be prompted for your Apple ID password, but you know it—you just set it.

And here’s the kicker. Using the same Find My iPhone app, you can sign in to the previous owner’s account with the new password (if two-factor authentication is enabled, you can use either a push approval or a one-time verification code generated in the device settings). Once you’re in, you can locate all other devices tied to that Apple ID and, for example, lock them or wipe them. After that, the former owner is essentially powerless—they can’t do anything except go to an Apple service center, because the devices will be protected by Activation Lock (iCloud Lock).

Interim results:

- Changed the user account password.

- Disabled Activation Lock (Find My iPhone).

- Changed the trusted phone number so the former account owner couldn’t do anything about it.

- Remotely wiped data from the former account owner’s other devices and/or locked those devices.

Now let’s take a look at what interesting data a user has stored in iCloud.

What’s Worth Looking for in iCloud?

Apple iCloud is a universal cloud service integrated into iOS (and macOS). It can store device backups (for all devices tied to the same Apple ID, not just the iPhone in your hand), photos and videos, various files, and app backups. iCloud also syncs data—almost in real time—such as contacts, call history, and email. Finally, passwords can sync through the cloud as well via iCloud Keychain. Let’s see whether it’s worth the effort to extract all of this data.

Backups

We’ve written about iOS iCloud backups many times before, so I’ll just recap: in terms of content, iCloud backups are equivalent to unencrypted local backups. This means items from the local keychain are included in the iCloud backup, but they’re encrypted with a device-specific hardware key and can only be restored to the exact device they were copied from. (That said, there’s another cloud-based mechanism that can recover passwords; more on that below.) Also, if Photo Library sync is enabled in the device settings (iCloud Photo Library), photos and videos are not included in either local or iCloud backups.

Why bother with cloud backups if we already have a local one? On the one hand, a local backup typically gives us more data — at minimum, we can decrypt Keychain passwords. On the other hand, we can only create a local backup from the device we currently have and only as of this moment, whereas the cloud may store up to the last three backups, and for all devices associated with the same account. So there’s still a chance to uncover something new.

You’ll need the Apple ID password you set in the previous step. If your account has two‑factor authentication enabled, you can receive the code on your device or generate it from Settings.

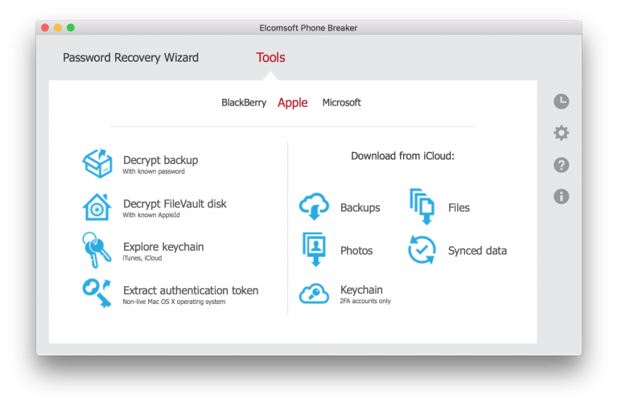

To access cloud backups, we typically use Elcomsoft Phone Breaker. In the main window, go to Tools → Apple → Backups and sign in with your username and password.

The backup will download in the local iTunes backup format; you can browse its contents with any tool that supports this format.

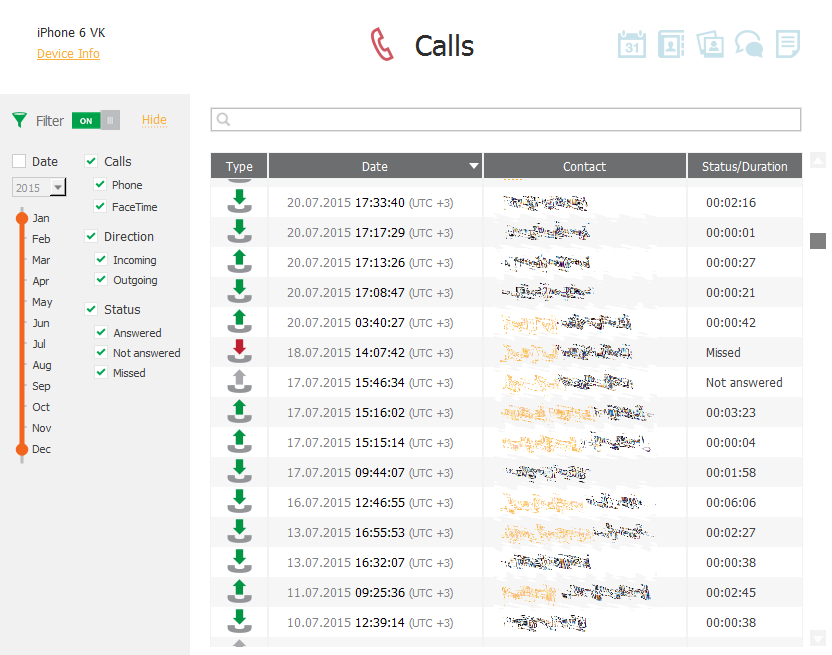

Call History and Synced Data

Cloud backups are interesting, but they can take a long time to download, and their practical value is questionable if you already have a local backup. But cloud-stored data isn’t limited to backups. A particularly useful iCloud category is synchronized data—for example, the call history for all calls placed and received on any phone registered to the account. Beyond calls, this includes Safari browsing history (again, synced across all of the user’s devices in near real time), bookmarks, open Safari tabs, notes, contacts, calendars, Maps-related data, and Wallet items (boarding passes and similar).

Extraction is fairly quick—just a few minutes. You can review the extracted data in Elcomsoft Phone Viewer.

iCloud Keychain: Apple’s cloud keychain

iCloud Keychain is a cloud service that syncs website logins and passwords from Safari, payment card details, and Wi‑Fi network information. The emphasis here is on password synchronization: there’s at least one way to configure iCloud Keychain so that passwords are synced through the cloud but aren’t stored in iCloud. Below, we briefly outline the possible iCloud Keychain usage scenarios.

Scenario 1

An account without two-factor authentication. If a user enables iCloud Keychain but doesn’t set an iCloud Security Code (a separate code that protects only the cloud keychain and nothing else), passwords aren’t stored in iCloud; synchronization occurs only among trusted devices. This scenario isn’t of interest to us.

Scenario 2

An account without two-factor authentication. If the user opted to use an iCloud Security Code, the passwords are already in the cloud, but accessing them requires that security code—which, per our assumptions, we don’t know. What to do? You can try enabling two-factor authentication on the user’s account; if you know the Apple ID password and can change the trusted phone number, this is straightforward. Thus, in theory, the task reduces to scenario 3 (we weren’t able to test this in practice).

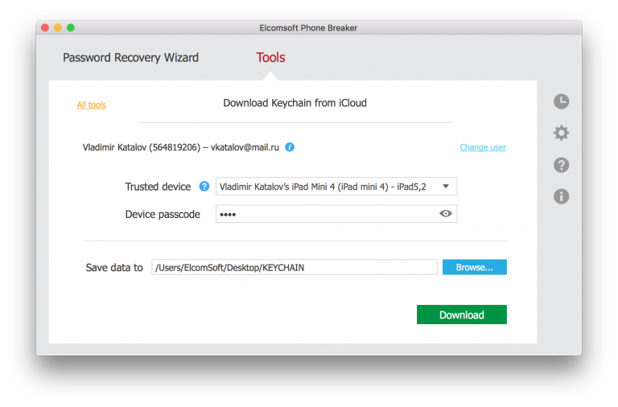

Scenario 3

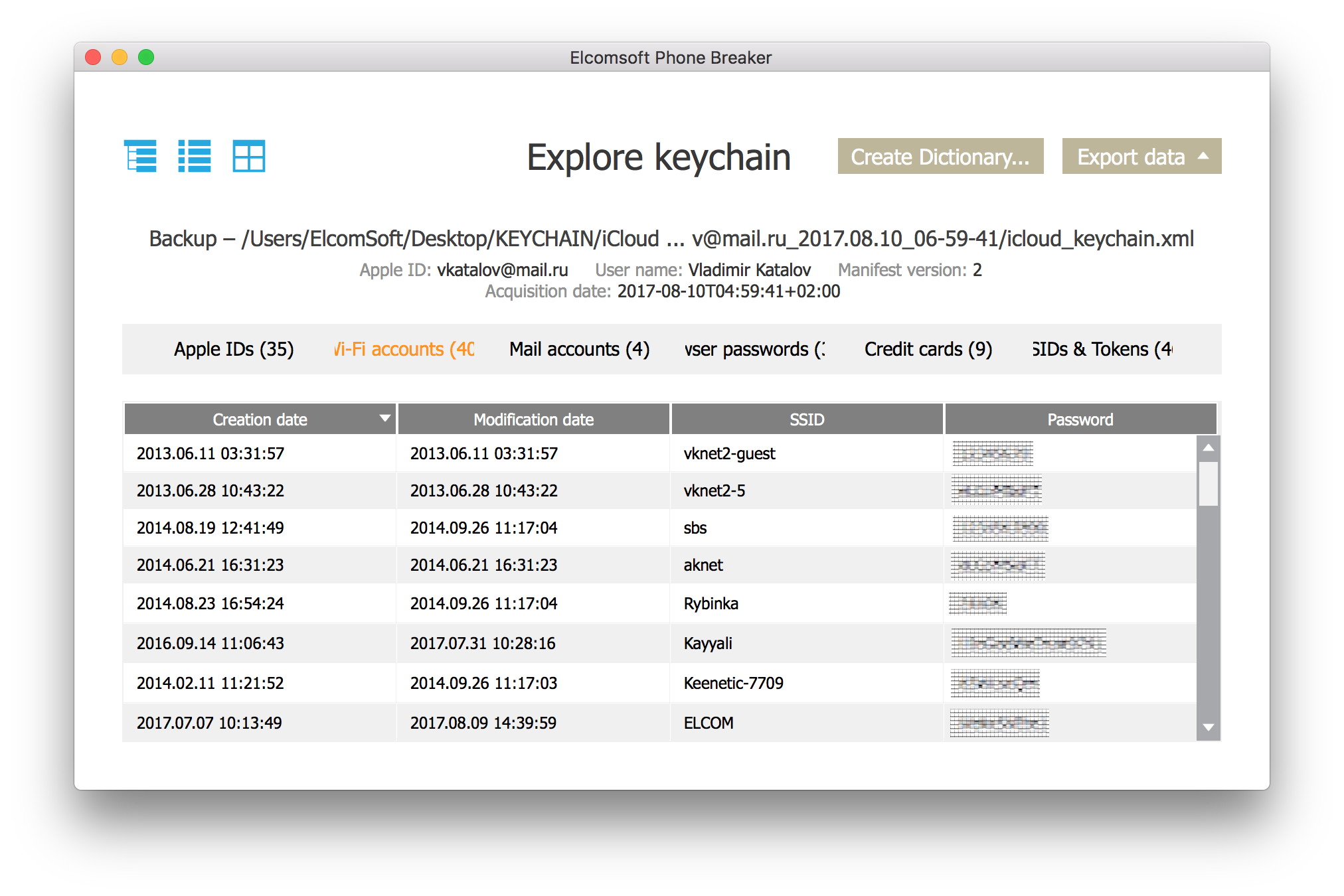

An account with two‑factor authentication enabled. The passwords are stored in iCloud, and to access them you’ll need to enter the Apple ID password and, in addition, the passcode/password for any device (iPhone, iPad, or Mac) that’s already enrolled in iCloud Keychain—including the iPhone in your hand. Problem solved: the passwords have been extracted.

Let’s take a closer look at extracting the cloud keychain.

- In Elcomsoft Phone Breaker, go to Tools — Apple — Download from iCloud — Keychain.

Sign in to iCloud (username, password, and the one-time 2FA code).

- From the list, select the Trusted device (the iPhone you’re holding) and enter its passcode in the Device passcode field.

- Return to the main screen and open Keychain Explorer. You’ll see passwords and auth tokens for the Apple ID (you might even find the user’s original Apple ID password here—purely for fun, you could put it back), Wi‑Fi network passwords, mail account passwords (who said “phishing”?), credit cards (not that we said “carding”!), and all passwords saved in Safari.

How Android Compares

Let’s say things are grim on iOS. How do they look in the parallel universe? What can you do with an Android phone if you know the lock screen password?

Turns out, not much. Yes, you can easily unlink the phone from the Google account and disable Factory Reset Protection (FRP). In fact, just removing that password in Settings will automatically turn FRP off. You can also create a local backup over ADB, but it’s of limited use: it won’t include passwords or other especially sensitive data. Physical extraction is where problems start: many phones can’t be rooted, which you need for a physical acquisition, and not every device is susceptible to bootloader exploits. That said, if you know the device’s passcode, decrypting the data partition is much easier.

Whether you can extract Chrome’s saved passwords is an open question: they’re stored in Google’s cloud, and you can access them in the browser at passwords.google.com. Even if the Google account password is already cached in the phone’s browser, Google will still prompt you to enter it again—manually. You can’t pull it from the cache. And one thing you definitely won’t be able to do is change the Google Account password in just a couple of clicks.

Conclusion

With the release of iOS 11, Apple effectively dismantled the multi-layered security model that previously existed in the iOS ecosystem. Now the device’s entire security hinges solely on the strength of its passcode—the lock-screen password. If an attacker gets hold of the device and learns the passcode (and for many older-generation devices that’s a matter of tooling, a modest budget, and a relatively short brute-force), the legitimate owner can quickly lose control of both the device and the associated account.

Practically all data, including passwords, can be extracted directly from the device via a local iTunes backup—the backup password can now be reset. The Apple ID and iCloud password can be changed in seconds, after which the device can be easily unlinked from iCloud (at that point the phone can be wiped and resold, and the user’s other devices can be locked and ransomed). And it doesn’t stop there: the attacker gains access to iCloud Photos, cloud-stored passwords, backups of every other device tied to the same account, call logs, and other synced data. Note that all this is possible just by knowing the lock-screen passcode of a single device! Even on Android, which we love to criticize for security holes, you can’t simply change the Google account password like that.

I don’t know about you, but personally I’m scared to leave the house with an iPhone. How do you protect yourself? It’s not clear yet. The one thing you can (and absolutely should) do is set a lock screen passcode with at least six digits. Starting with iOS 10, Apple recommends six‑digit passcodes. Brute-forcing those is currently not technically feasible. That said, if someone shoulder‑surfs your code or forces you to reveal it, we’re back to square one.