One of the most popular apps back in the Symbian and Nokia era was the so‑called call blacklist, which let phone owners shield themselves from unwanted callers. While modern smartphones sometimes build similar features into their system images, they often boil down to a simple, permanent block on a contact in your address book. For research purposes, let’s look at how this mechanism actually works in practice. We’ll assume you’re a regular reader of the Coding column, you live in Android Studio, and you swear exclusively in Java.

So where are the buttons?

Whether the app is official or unofficial (for personal research only, of course), it’s just as bad if it crashes because the device lacks telephony features (e.g., a Wi‑Fi‑only tablet). So the first thing to do is check for them:

PackageManager pm = getPackageManager();

boolean isTelephonySupported = pm.hasSystemFeature(PackageManager.FEATURE_TELEPHONY);

boolean isGSMSupported = pm.hasSystemFeature(PackageManager.FEATURE_TELEPHONY_GSM);

As you can see, we called PackageManager’s hasSystemFeature method with the FEATURE_TELEPHONY constant. It’s also a good idea to additionally check for a GSM radio using the FEATURE_TELEPHONY_GSM constant.

If both constants evaluate to false, we’ve misidentified the device—nothing we can do. In this case, the app should terminate and, on exit, prompt the user to switch devices 😉

Answering Your First Call

Using the PhoneStateListener class in Android, you can monitor the phone’s state, but only if the app has requested the READ_PHONE_STATE permission in its manifest.

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_PHONE_STATE"/>

Next, you need to override and register the onCallStateChanged method in your PhoneStateListener implementation to receive notifications about changes in the phone call state. A ready-to-use implementation is shown below:

PhoneStateListener stateListener = new PhoneStateListener() {

public void onCallStateChanged(int state, String incomingNumber) {

switch (state) {

case TelephonyManager.CALL_STATE_IDLE: break;

case TelephonyManager.CALL_STATE_OFFHOOK: break;

case TelephonyManager.CALL_STATE_RINGING:

doMagicWork(incomingNumber); // Incoming call from number incomingNumber

break;

}

}

};

...

TelephonyManager.listen(stateListener, PhoneStateListener.LISTEN_CALL_STATE); // Put this in the activity's onCreate

When a call comes in, the integer parameter state takes the value CALL_STATE_RINGING, which triggers our payload—whether weaponized or benign—via the doMagicWork function.

In the wild, this approach to handling an incoming phone call is used almost never. The catch is that the app has to be running in the foreground at the moment the call comes in—it’s hard to imagine a practical use for that (maybe for debugging), so let’s move on.

Answering a Second Call

When the phone’s state changes (for example, when an incoming call is received), the TelephonyManager broadcasts an Intent with the action ACTION_PHONE_STATE_CHANGED.

Intents are an interprocess messaging framework. They’re widely used in Android to start and stop activities and services, broadcast messages system-wide, and implicitly invoke activities, services, and broadcast receivers.

Broadcast receivers are components that let an app listen for intents and react to any received actions. They implement an event-driven interaction model between apps and the system.

As in the previous case, the app must declare the READ_PHONE_STATE permission in the manifest:

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.READ_PHONE_STATE"/>

There we also register a broadcast receiver that can listen for intent broadcasts:

<receiver android:name="PhoneStateChangedReceiver" >

<intent-filter>

<action android:name="android.intent.action.PHONE_STATE" />

</intent-filter>

</receiver>

With this approach, we can always receive information about incoming calls, even when the app isn’t running.

The intent that reports a change in the phone’s state will include two extras: EXTRA_STATE_RINGING, which indicates an incoming call, and EXTRA_INCOMING_NUMBER, the caller’s phone number.

public class PhoneStateChangedReceiver extends BroadcastReceiver {

@Override

public void onReceive(Context context, Intent intent) {

String phoneState = intent.getStringExtra (TelephonyManager.EXTRA_STATE);

if (phoneState.equals(TelephonyManager.EXTRA_STATE_RINGING)) {

String incomingNumber = intent.getStringExtra(TelephonyManager.EXTRA_INCOMING_NUMBER);

doMagicWork(incomingNumber); // Incoming call from number incomingNumber

}

}

}

This is exactly the approach you should use in practice.

Hang Up!

So, the phone is happily ringing, the incoming number is identified, and our broadcast receiver has been triggered. What’s next?

If you’re thinking about a blocklist approach or a bot under remote control, it would be useful to learn how to hang up calls without alerting the user. The phone’s hardware stack is much like Windows ring 0 in the sense that it’s a low-level system component. Because of that, there’s no standard way to reach it—especially if your device isn’t rooted.

One approach is to use the Android Interface Definition Language (AIDL) to facilitate interprocess communication (IPC) between system components.

To do this, add the ITelephony.aidl interface file to your project with the following definition:

package com.android.internal.telephony;

interface ITelephony {

boolean endCall();

void answerRingingCall();

void silenceRinger();

}

The following code grabs the interface and, using reflection, hangs up the call:

import java.lang.reflect.Method;

import com.android.internal.telephony.ITelephony;

...

TelephonyManager telephony = (TelephonyManager) context.getSystemService(Context.TELEPHONY_SERVICE);

try {

Class c = Class.forName(telephony.getClass().getName());

Method m = c.getDeclaredMethod("getITelephony");

m.setAccessible(true);

telephonyService = (ITelephony) m.invoke(telephony);

telephonyService.endCall();

} catch (Exception e) {

e.printStackTrace();

}

For this to work, the app needs one more permission in the manifest:

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.MODIFY_PHONE_STATE"/>

Because of this, this method won’t work on devices running Android 2.3 and above, since starting with Gingerbread this permission is treated as a system permission, and attempting to use it will cause the app to crash:

Neither user 10031 nor current process has android.permission.MODIFY_PHONE_STATE

But isn’t Google Play full of apps that implement a blocklist? How do they actually work? Roughly, you can split them into two groups (besides those that properly use AIDL): fakes and… hacks. The former only pretend to work, occasionally showing “blocked” call (and SMS) stats in the notification shade. In return, they demand internet access and download tons of ads, which they shove in your face nonstop. The bet is that the user won’t catch on right away, so the app still gets to deliver its share of banners—pure homeopathy. These apps hardly belong in a “Coding” section, so we’ll skip them.

Apps in the second group try to end the call using non‑standard tricks—for example, by pretending to be the user and simulating button presses:

public static void answerPhoneHeadsethook(Context context) {

// "Press" and "release" the headset button

Intent buttonDown = new Intent(Intent.ACTION_MEDIA_BUTTON);

buttonDown.putExtra(Intent.EXTRA_KEY_EVENT, new KeyEvent(KeyEvent.ACTION_DOWN, KeyEvent.KEYCODE_HEADSETHOOK));

context.sendOrderedBroadcast(buttonDown, "android.permission.CALL_PRIVILEGED");

Intent buttonUp = new Intent(Intent.ACTION_MEDIA_BUTTON);

buttonUp.putExtra(Intent.EXTRA_KEY_EVENT, new KeyEvent(KeyEvent.ACTION_UP, KeyEvent.KEYCODE_HEADSETHOOK));

context.sendOrderedBroadcast(buttonUp, "android.permission.CALL_PRIVILEGED");

}

An unconventional yet effective method is to turn the volume of an unwanted call all the way down to zero:

AudioManager audioManager = (AudioManager)context.getSystemService(Context.AUDIO_SERVICE);

int ringerMode = audioManager.getRingerMode();

audioManager.setRingerMode(AudioManager.RINGER_MODE_SILENT);

Using the AudioManager object, we first retrieve the current ringer mode with getRingerMode(), then switch the device to silent mode by setting AudioManager.RINGER_MODE_SILENT.

Once the call ends (the current state changes to EXTRA_STATE_IDLE), restore the original mode:

audioManager.setRingerMode(ringerMode);

But even then, you’ll still need special authorization:

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.MODIFY_AUDIO_SETTINGS" />

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_SETTINGS"/>

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.WRITE_SECURE_SETTINGS"/>

We’re not actually blocking the number here; we’re just not answering the call. The upside is that this approach doesn’t require any special tricks.

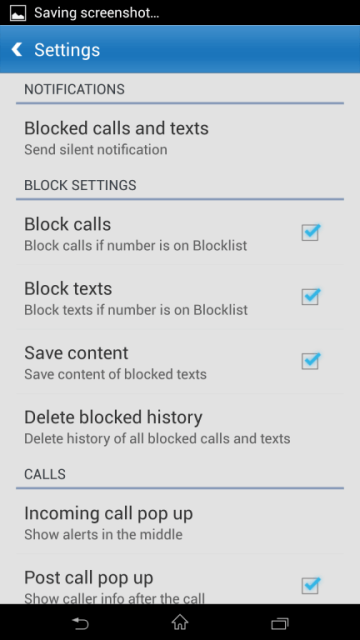

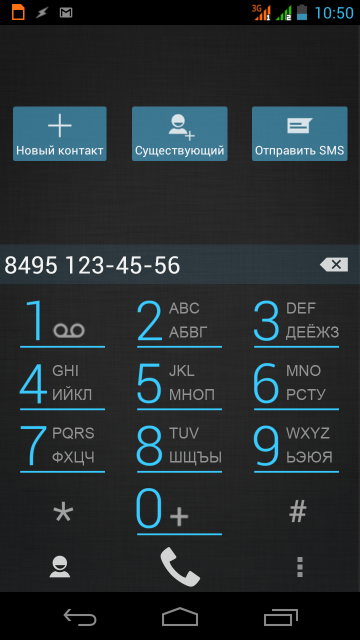

Some apps try—often with mixed results—to access or control the buttons on the incoming call screen, as shown here.

info

A related issue is displaying information on top of the incoming call Activity (or even fully replacing the window to disguise it), but for security reasons Android doesn’t allow apps to create their own Activities for this purpose. However, this restriction doesn’t apply to system windows. An interesting article on the topic.

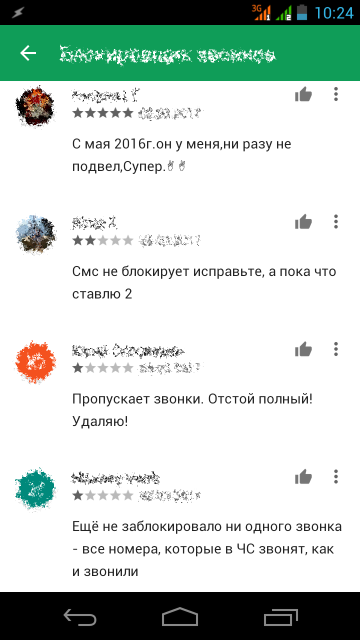

In practice, many “hacks” that work fine on some devices either don’t work at all on others or, worse, crash the app when an incoming call arrives. As a result, ratings for such apps swing wildly—from one star (“Nothing works, give me my money back!”) to five (“Been using it for twenty years, no complaints!”).

We could’ve wrapped it up right there—if the “good corporation” hadn’t suddenly pulled a surprise chess move.

Google’s Built‑In Blocklist

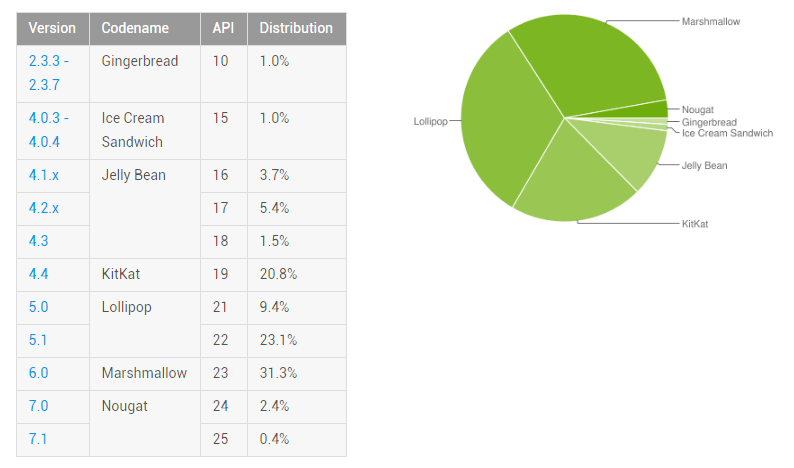

Android 7.0 Nougat (API 24) introduced the class BlockedNumberContract—a system-wide blocklist implemented as a first-class OS feature rather than a phone firmware component. All calls (as well as SMS and emails) from senders on this list are automatically rejected by the system.

BlockedNumberContract is a standard content provider that can be accessed by system apps and by the user-selected default SMS and telephony apps. The “default” status must be explicitly set by the user—this has been part of Android’s security model since version 4.4 (KitKat). For telephony, being the default app grants privileges not only to handle incoming and outgoing calls but also to modify related databases (for example, delete entries from the call log). Consequently, be cautious about apps—even from Google Play—that try to become the default dialer and also have unrestricted internet access; the risk of data exfiltration is quite high.

Working with BlockedNumberContract is much like working with a database: you use the familiar insert, delete, and, of course, query operations.

Content provider — a shared, persistent storage layer (typically an SQLite database) that holds and manages an app’s data. It’s the preferred mechanism for exchanging data between different applications.

To block a phone number, call the standard getContentResolver(). method:

ContentValues values = new ContentValues();

values.put(BlockedNumbers.COLUMN_ORIGINAL_NUMBER, "1234567890");

Uri uri = getContentResolver().insert(BlockedNumbers.CONTENT_URI, values);

Despite its name, the COLUMN_ORIGINAL_NUMBER column can contain not only a phone number but also an email address:

values.put(BlockedNumbers.COLUMN_ORIGINAL_NUMBER, "12345@abdcde.com");

Removing a number from the blocklist is just as easy:

ContentValues values = new ContentValues();

values.put(BlockedNumbers.COLUMN_ORIGINAL_NUMBER, "1234567890");

Uri uri = getContentResolver().insert(BlockedNumbers.CONTENT_URI, values);

getContentResolver().delete(uri, null, null);

To check whether a number is on the blacklist, use the isBlocked( method.

Finally, to fetch all the rejected ones in one go:

Cursor c = getContentResolver().query(BlockedNumbers.CONTENT_URI,

new String[]{BlockedNumbers.COLUMN_ID, BlockedNumbers.COLUMN_ORIGINAL_NUMBER,

BlockedNumbers.COLUMN_E164_NUMBER}, null, null, null);

So the tricks discussed in the previous section will gradually fade away. The only question is how soon. Android 7’s share is still essentially a rounding error.

Placing a Call

There are two fundamentally different ways to place a call on Android. The first, and simplest, is to launch the standard activity and pass it the phone number to dial as a parameter:

Intent call = new Intent(Intent.ACTION_DIAL, Uri.parse("tel:8495-123-45-56"));

startActivity(call);

Here, the call-initiating intent Intent. is used, and the number is passed as a URI path with the required tel: scheme. On the smartphone screen, the user will see the standard dialer with the number prefilled.

The standard dial action lets you change the number right before placing the call, so the app doesn’t need any permissions in its manifest.

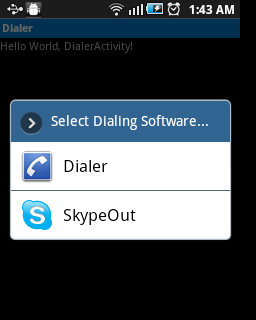

The second option is to intercept intents that are normally handled by the default app and launch your own activity. In that case, rendering the on-screen dial pad and implementing contact search (and that’s far from a complete list) falls on the developer.

Furthermore, since this case requires authorization:

<uses-permission android:name="android.permission.CALL_PHONE"/>

Starting with Android 4.4, the app won’t run unless it’s set as the default, and users are unlikely to switch away from their familiar dialer on a whim.

As you can see, Google has done a solid job hardening its dialer, and malware that secretly calls premium-rate short codes hasn’t been observed in the wild (yet?).

Ode to the Manifest

If you follow the Coding section, you’ve probably noticed that any potentially risky action on Android requires an explicit permission. Despite the vulnerabilities out there (when was the last time you got patches?) across different system components, the biggest source of problems is usually the user. Of course, if you ever attract the CIA’s attention, no amount of denying app permissions will save you, but in everyday life you should be extremely cautious about anything you install—even if it’s from Google Play. Do you really need a calculator that asks for internet access and permission to send SMS?

Conclusion

Today we took a look at one of the core components of a modern smartphone—the telephony stack (though messaging apps might have a different opinion). As usual, not everything works quite the way we’d like, and the tinkering will continue for a while yet—that’s just a programmer’s lot. In any case, Hacker will keep you posted.